© Donal G. Burke 2013

The medieval castle of Athenry is one of a number of early to mid thirteenth century stone castles that, in their original state, consisted of an isolated keep that took the form of a simple hall at first floor level over a lower or ground floor chamber, surrounded by and detached from a defensive curtain wall. Classified by some modern architectural historians as a ‘hall-keep’ castle, others of this type include that located at Moylough in the east of County Galway and Greencastle in County Down.[i] Like Athenry, many of these were also extended by the later addition of another floor above the keep’s hall.

The keep of Athenry Castle viewed from the south.

Early history

The Anglo-Norman William de Burgh was given a grant of the O Connor’s kingdom of Connacht by King John in the early years of the thirteenth century but he died before he could gain control of the territory. It was only in the summer of 1235 that the might of the Anglo-Norman colony in Ireland was assembled under the Justiciar and de Burgh’s son Richard to subdue the Irish of Connacht and secure for de Burgh the lordship of Connacht. For those adventurers who participated, their share of the spoils would be fertile estates in the newly acquired territory. The Gaelic kingdom was overrun and the O Connors routed. De Burgh’s supporters were granted their own territories in the new lordship, while the O Connors were consigned to an area to the north-east known to the Anglo-Normans as the Kings Cantreds, about the later County Roscommon and part of East Galway.

Richard de Burgh kept much of the best lands for himself under his own immediate control and established his principal seat in Connacht at Loughrea. One of the chief recipients of new lands in the lordship was the Anglo-Norman Meyler de Bermingham, who received a grant of extensive lands in Clantayg, about the modern Athenry in what would later be central County Galway, while his father Peter acquired lands about Dunmore in north-east Galway and about the later County of Sligo. The Irish annalists record that it was about two years later before the colonists began to consolidate their conquest, when ‘the Irish barons came into Connacht and began the building of castles therein’ although the scattered presence of various motte and bailey style early fortifications may indicate the earliest stage of settlement prior to the conquest proper.

It is generally agreed that de Bermingham constructed the early stone castle at Athenry between 1235 and 1241 on a site commanding a ford or crossing point on the River Clareen.[ii] The town of Athenry was developed almost immediately as a settlement centre to the south and south west of the castle, receiving a charter to hold a market in 1241. Another Anglo-Norman with landed interests at an early stage in Athenry was Robertus Braynach (ie. Robert Breathnach, ‘the Welshman’ or Walsh), a knight (‘milite’) from whom de Bermingham purchased a plot of land within the confines of the newly laid out town to present to the Dominican Order to facilitate the construction of a new friary, immediately to the south of the castle.[iii]

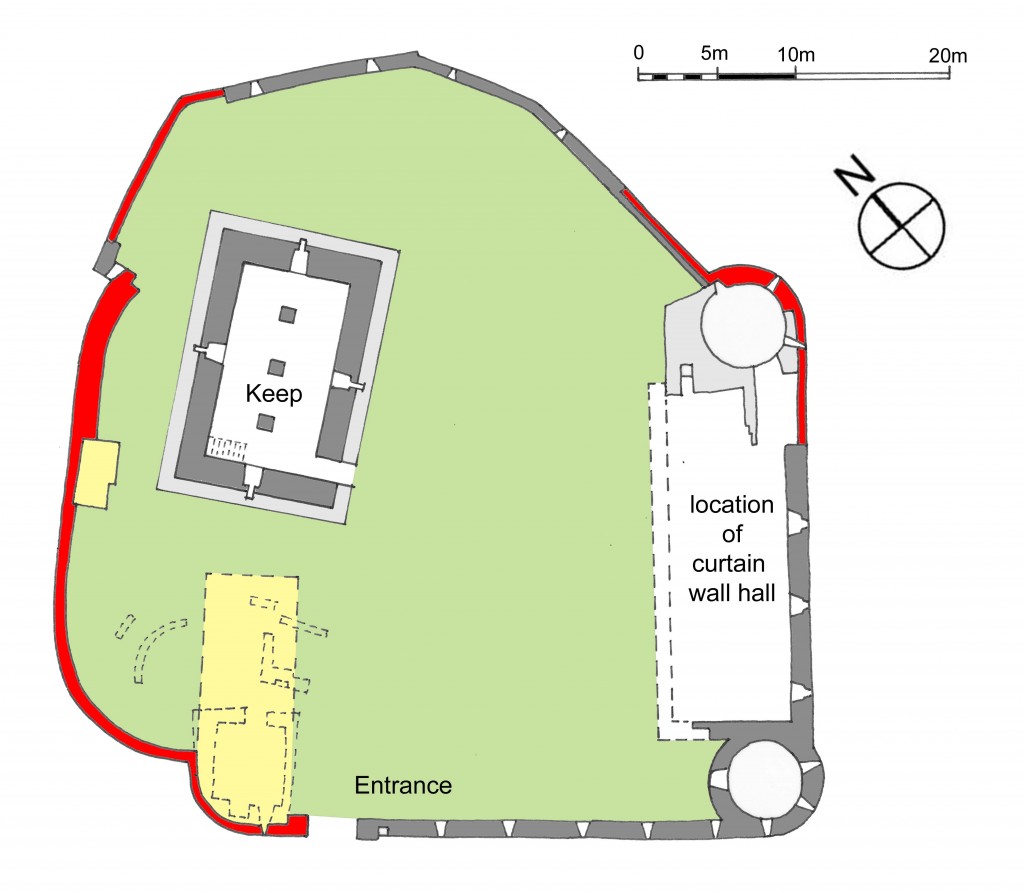

Sketch plan of Athenry Castle (after Papazian, Collins and McCarthy) showing medieval walls (in grey), modern reconstructed wall (in red), approximate location of twentieth century visitor facilities (in yellow) and traces of early walls within castle grounds (shown dashed).

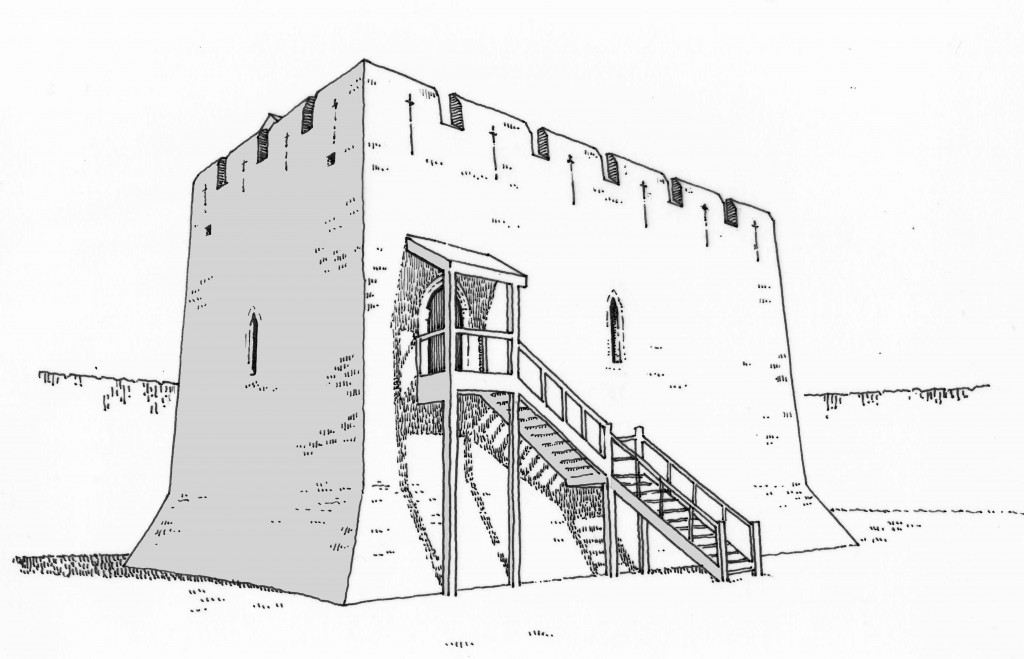

The keep

The castle building as originally constructed consisted of a simple isolated two-storey stone keep structure, rectangular in plan, the entrance door to which was located at first floor level. The entrance door would appear to have been accessed externally by a timber stair structure and possibly protected or covered by a sheltering canopy or timber structure. It has been suggested that this entrance may have originally been protected by a fore-building, possibly made of timber whose remains have not survived.[iv] Two recesses or sockets built into the stone wall behind the position of the original door, one on each side of the door, served at one time to hold a timber beam used to secure the door.

Unusually for a castle of this early type, the principal entrance doorway was given a certain amount of elaboration, with engaged-columns and carved stone capitals either side, more often found in church buildings of this date. The elaboration on this doorway and the slightly greater elaboration on the adjacent window at the same level may suggest that these were intended to be for display and the doorway itself may not have been covered over by any fore-building or covering.

The keep is similar to certain early stone castles such as that built at Moylough, also located in what would later be County Galway and mid-way between the de Bermingham centres of Athenry and Dunmore. In addition to building style, both keeps were similar in dimensions, with Athenry approximately 16.8m long and 10.7m wide while Moylough measured 16.2m long and 10.7m wide.[v] Like Athenry, Moylough was also entered at first floor level.

For defensive purposes the ground (or lower) floor was provided with an external batter or sloped surface and lit only by narrow slit openings, restricting access. An internal timber flight of stairs or ladder, along the south-western gable wall and near the first floor entrance door, would appear to have been the only access access to the ground floor below. This lower floor may have been used for storage purposes or similar, given its lack of natural daylight. From an eighteenth century drawing it would appear that at one stage a stairs in this location may have been enclosed by a stone wall.[vi]

The first floor consisted primarily of a large hall chamber, served by one tall arched window with a trefoil-pointed head in each of the four external walls, slightly wider than those below and more elaborate, each displaying carved capitals similar to those found atop engaged columns either side of the main entrance door. A garderobe or latrine was constructed in the northern corner of the first floor wall, diagonally opposite the entrance door and projecting from the external wall, from which a chute discharged to a cess pit externally below.

The first floor hall viewed from the south-west. The timber stairs descending against the opposite wall is a modern insertion and serves as an emergency escape stairs from an audio-visual room at second floor level.

The first floor hall viewed from the north-east, with the principal entrance door on the left. Above the door and on the opposite wall are the remains of a stone arch and wall sockets that would appear to have supported a floor in that area and indicate the earlier floor level above the hall.

The first floor garderobe or latrine.

As appears to have been the case at Moylough and a number of early stone castles, there is no evidence of a fireplace built into the structure of the walls.[vii] It is thought likely that a fire was lit in a hearth or brazier about the centre of the room, the smoke exitting through an opening in the roof above.

Two square outlet holes in the south-western gable of the keep and two in the north-eastern gable served as rainwater discharge outlets from the wall-walk inside the original parapet crenellations (or battlements) and indicated the level of the original roof.

Conjectural sketch by the author of Athenry castle circa 1250, prior to later additions. The type of covering at the main entrance is uncertain and may have been of a different construction than that indicated, given the greater difficulty in defending the door from the battlements above if the door was covered by such a canopy or roof.

The keep was enlarged by the raising of the roof and the addition of another floor at second floor level, apparently in the late thirteenth century. The lack of any significant number of windows at this new level, together with the remains of an internal stone vault and a number of beam sockets built into the walls above the entrance door and three corresponding sockets on the opposite wall to provide support for timber beams suggest that this extension may have taken the form of a gallery above the south-western end of the first floor.

Long narrow cruciform slits or loops in the merlons (ie. the vertical masonry sections of the crenellations or battlements) on all sides above this new floor provided defending bowmen with both a horizontal and vertical range of fire and allowed the defenders a steep angle of fire to the ground immediately below the walls. A series of outlets in the stone walls between the loops facilitated the discharge of rainwater from the base of the new roof level and indicated the new level of the wall-walk behind the crenellations. Access to the battlements at roof level was achieved from the southern corner on this new floor by a straight narrow mural stairs rising from a deep window embrasure.

The mural stairs providing access to the battlements from a second floor window embrasure.

Steep stone gables at roof level and vaulting of the ground floor ceiling, supported on three substantial stone columns, are believed to be fifteenth century additions. Traces of the wickerwork mats upon which the stone was set into the mortar during the construction of these vaults would still be evident into the twenty-first century. It is unclear if it was at this stage or later that an opening was made in the external wall at ground floor level, immediately below the first floor entrance door, to provide more convenient access to the lower level.

Vaulted ceiling at ground floor level.

The curtain wall and associated hall

At about the same time that the keep was initially built, a stone curtain wall, approximately 1m to 1.8m wide, irregular in plan and possibly a surrounding ditch was constructed about the keep but detached from the latter.[viii] As the curtain wall was being built, the uneven ground to the southeast of the keep was built up and levelled with soil and refuse deposits to facilitate the construction of a rectangular hall.[ix]

The hall, 21.3m long and 8.1m wide, was planned to lie between two round mural towers along the curtain wall and form part of that same wall.[x] Later archaeological excavations suggested that work first commenced on the western wall of this hall, nearest the keep, and its southern wall then built about the southern round mural tower.[xi] The eastern wall of the hall, between the southern and eastern curtain wall towers, is believed to have been built last and formed part of the curtain wall. The hall appears to have been a simple structure and well lit, with four tall windows built into the eastern wall.

The site of the former curtain wall hall to the south-east of the keep.

While it is unclear, another stone medieval building may also have existed along the north-eastern section of the curtain wall.[xii]

The castle grounds appears to have been entered from the south west, about the location of the modern entrance, which would suggest that the castle site was accessed through the town. Evidence of a square tower built along the curtain wall exists about this position but it is uncertain if this served as a gatehouse or guardhouse. [xiii]

The decline of the Anglo-Norman lordship of Connacht

A decisive battle was fought about Athenry in 1316, after the de Burgh Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht had lost effective control over the western lordship during the Bruce war. The defeat of the Gaelic forces by the Anglo-Normans re-established the de Burgh dominance of the lordship.

The castle and town of Athenry witnessed considerable conflict over the centuries, as the organised Anglo-Norman colony in Connacht declined during the late thirteenth and fourteenth century and as the Gaelic chieftains regained territory. The authority of the Crown simultaneously declined to the degree that Ireland could be described by one late medieval Gaelic poet as ‘fearann claíomh’or ‘sword land.’ Having been an important commercial centre in the medieval Anglo-Norman lordship the town continued as such within the late medieval territory of Clanricarde, the lordship ruled by the Burkes of southern Connacht, descendants of a junior line of the de Burghs who came to rule much of what would later be central and eastern County Galway after the last of the de Burgh earls was murdered in 1333.

The town appears to have maintained its position as a centre of trade and commerce in the late fourteenth and fifteenth century, with the presence of burgesses and property holders with such names of foreign extraction as Blake, Brun (Browne), Joy, Steven, Wydyr, Calf, Baudekyn (Bodkin), Erla, Redde and others.[xiv]

Damage done to the castle and town in the late sixteenth century

By the mid sixteenth century the town and its castle had suffered considerably during disturbances and power struggles within Clanricarde and continued to suffer throughout that century as the representatives of the Tudor Crown of England strove to regain greater control of the west of Ireland.

When the Lord Deputy Sir Henry Sidney visited Athenry in 1567 on his way between Galway and the Loughrea residence of Richard Burke, 2nd Earl of Clanricarde, he described it as a great and ancient town and, although large and well-walled, in a pitiful state with its population dramatically depleted to the extent that it was near abandonment. The wider territory was upset by internal strife between Ulick and John Burke, the two young sons of Clanricarde, who intermittently vied with one another for the eventual succession to the earldom. Sidney noted that the Earl of Clanricarde could not deny that ‘he helde a hevie hande’ over the townspeople, who appealed to the Lord Deputy for assistance. On that occasion Sidney ordered Clanricarde to cease taking exactions from the town and make some recompense to the citizens.[xv]

The town of Athenry was subject to a succession of debilitating raids and assaults at the hands of those opposed to the English provincial government in the last three decades of the sixteenth century. The town and its castle, like that at Ballinasloe, was used by the English adminsitration in Connacht as a garrison for its soldiers and as such was a threat to those opposed to the Crown. In 1570 Athenry was raided in a dispute between the O Brien Earl of Thomond and the English administration.[xvi] The castle itself appears to have been damaged about mid July 1572 when it was reported that Clanricarde’s sons, Ulick and John Burke, who were in open rebellion against the Crown and with the suspected connivance of their father, destroyed the strategic castle at Meelick on the River Shannon, threathened that of Ballinasloe by the River Suck and ‘destroyed the walls of the town of Athenry and also its stone houses and its castle and they so damaged the town that it was not easy to repair it for a long time after them.’[xvii]

When the Earl sought a pardon from the Queen for his son’s actions the Crown insisted on making the repair of the ruinous town of Athenry an integral part of any pardon. The remaining inhabitants of Athenry entrusted Gregory Bodkin, a former alderman of the town, to further their complaints against the rebels and their case for restitution and in June of 1573 he travelled to England to deliver his recommendations to one of the Queen’s chief ministers.[xviii] Bodkin appears to have recieved a favourable response and the Lord Deputy and the Council of Ireland informed the Earl of the requirement to restore Athenry and ‘to see that his sons and other malefactors express a fruitful penitence in that affair.’[xix] The financial cost involved in the repair of the town was substantial and the Earl and his sons proved reluctant to acquiesce to the Crown’s demands.[xx]

Both sons submitted to the government about August 1574 and in September the Lord Deputy and Council ordered that a cess of 1,200 kine (i.e., cows, used as a unit of currency from ancient times in Ireland) would be levied upon the territory of Clanricarde for ‘the re-edifying of the town, abbey, church and walls of Athenry.’[xxi] The costs imposed upon Clanricarde’s country for the restoration of Athenry and the growing power of the Crown’s officials at the expense of the great lords and chieftains such as Clanricarde was a cause of grave concern to the earl and contributed to his growing disaffection from the English cause.

The Earl’s sons continued as a focus for significant unrest in the province and in 1576 the Lord Deputy Sidney had them arrested and taken to Dublin. After their commital in March of that year, Sidney travelled through Athenry and found the town had still not recovered since he was last there nine years before.[xxii] It was, he reported, ‘the most wofall spectacle that ever I looked on in any of the Queen’s Dominions, totally burned, Colledge, Parishe Churche, and all that was there, by the Earle’s Sonnes, yet the mother of one of theim was buried in the churche.’[xxiii] Sidney issued orders for the re-edification of the town, divided it into two almost equal parts and work had begun on fortifications before he left.

View from the castle of the site of the Collegiate Church, burned by the sons of the Earl of Clanricarde in the 1570s.

By late June the Earl’s sons had crossed back over the River Shannon into Connacht. One of their first actions was to burn Athenry, undertaken by a band led by John Burke. They ‘destroyed the few houses which were lately built there, set the new gates on fire, dispersed the masons and labourers who were working and broke down and defaced the Queen’s arms.’[xxiv] A number of the Lord Deputy’s workmen were killed and the fortifications left unfinished. Sidney noted in a later memoir that ‘in this town was the sepulchre of their forefathers, and the naturall mother of the same John buried.’ They burned this church, the ‘chief church of the town’. John was reputedly asked to spare the burning of the church ‘where his mother’s bones lay’ but in response he ‘blasphemously swore, that if she were alive and in it, they would burn both the church and her too, rather than any English churle should enhabit or fortifye there.’[xxv]

The Lord Deputy moved swiftly to quell the rebellion and suspecting the Earl of covertly supporting his son’s rebellion, had him arrested and taken first to Dublin and thereafter to England where a case was prepared accusing him of treason.

The Earl’s sons agitated against the government following the confinement of their father while still intermittently fighting with one another over the future succession to the earldom and by late November 1580 had again burned part of Athenry.[xxvi] The Earl was held in captivity and detained in England until he fell dangerously ill in the summer of 1582 and allowed return to Ireland.[xxvii] The Crown decided finally to allow the Earl to return to Ireland but the issue of the restoration of Athenry was still tied in with his release and a fine of 6,000l. was imposed upon Clanricarde to provide for the rebuilding of the same among other impositions.[xxviii] He died not long after returning later in the year.

The condition of the castle in 1582

The castle at Athenry appears to have been still in a poor condition in late 1582. Barnaby Googe, Provost Marshal of Connacht (an officer in the Queen’s provincial administration), while recovering at Athlone with an injured leg in December of that year, wrote of being stationed at Athenry castle and that the castle was at that time without ‘floor or covering.’[xxix] If these were provided, he felt that the castle would have been of sufficient strength to be held by the garrison there.

Athenry was reported to have been burned again by January 1597 during the rebellion of O Donnell and the Nine Years War, but it is unclear if this was a reference to the town, the castle or both.[xxx] The town was again destroyed during the same wars about March 1601, on that occasion by the English Captain Mostyn or Mostian, who revolted and joined the rebel forces opposed to the Queen.[xxxi] By 1602 it was referred to as the ‘waste town of Athenry.’[xxxii]

Archaeological excavations undertaken in the late twentieth century revealed little evidence of habitation at the site of the castle during the seventeenth century, suggesting that the site may not have been used as such from that period. As the excavations failed to expose stratified material dating to the seventeenth century, the archaeologists were of the view that this absence may relate to the abandonment of the castle at that time, noting that fifteenth and sixteenth century gaps in the stratigraphic record ‘are paralleled by many other castle and non-castle sites.’[xxxiii]

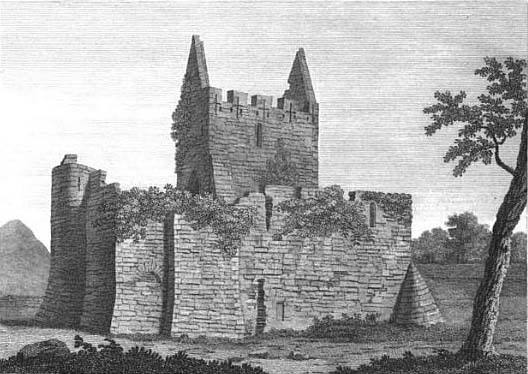

Bigari’s images of the castle circa 1779

When Captain Francis Grose compiled information on the antiquities of Ireland about 1791, he described Athenry castle as then consisting of ‘a square tower, well-built, of brownish stone, standing in a large area, surrounded by a wall of irregular figure, composing a fort of hexagon, flanked on one side by two towers. There is a projection at the entrance and a walk and parapet on the wall, in which one embrasure is visible and probably there were more, which are now overgrown with ivy.’[xxxiv]

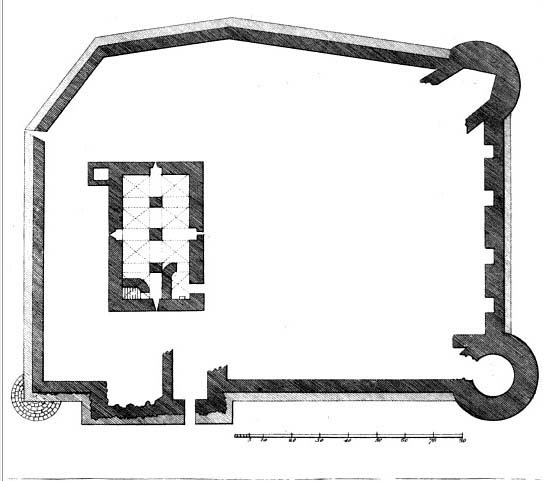

Two drawings were used to illustrate the castle in Grose’s work, both engravings of originals completed about 1779 by an Italian landscape draughtsman named Angelo Maria Bigari. One of these plates gave a plan of the castle grounds, with the ground floor plan of the hall keep.

Engraving taken from Bigari’s plan of Athenry Castle circa 1779.

The western curtain wall was in a reasonable state of preservation at that time, and both a plan and an elevation by Bigari depicted the castle and walls from the north show a different layout of the curtain wall at its western-most corner and near the modern entrance than that reconstructed in the twentieth century. Bigari’s image showed what appears to have been the remains of a more defined gatehouse structure projecting from the curtain wall in the vicinity of the modern entrance gate and a more acute angle on plan at the western-most corner of the curtain wall, strengthened by a low sub-circular buttress.[xxxv] (Remains of a square structure about the modern entrance would suggest that, if the structure shown as projecting from the curtain wall by Bigari was intended as this building, then it may rather have been immediately inside the line of the curtain wall.)[xxxvi]

Engraving taken from Bigari’s view of Athenry Castle circa 1779.

The plan of the curtain wall showed all four window openings in the eastern wall, between the two curtain wall towers intact at that time. In what appears to have been a reasonably accurate depiction of many of the surviving features of the hall keep, including a low wall about the external cess pit, it depicted two substantial stone walls in that lower ground floor level that are not evident in the modern remains. One wall partially enclosed a stair leading from the first floor to the ground floor, while another appeared immediately inside the external

entrance that had been created by that time in the lower floor wall.[xxxvii]

Early twentieth century

The keep was in a ruinous condition until the twentieth century, while the curtain had fallen into significant disrepair and several areas of masonry fallen. By the mid twentieth century little remained of western curtain wall and its eastern tower. The western wall of the hall had largely disappeared, with only traces remaining of its northern and southern walls adjoining the curtain wall towers. While a large part of the hall’s eastern wall remained, the northernmost of its four windows in that wall had disappeared when part of the surrounding wall had fallen. This window had survived into the eighteenth century and was intact in the late eighteenth century when represented by Grose but had fallen thereafter. When the architect Harold G. Leask visited the site prior to 1951 ivy concealed certain architectural features on the keep from view but assessed the keep as ‘still very well preserved.’[xxxviii]

Restoration work in the 1960s and circa 1990.

In the 1960s restoration works were undertaken at the castle and this section of the eastern wall was rebuilt but without a window. At that same time much of the western curtain wall was rebuilt, as was part of the eastern curtain wall tower.

The keep at Athenry circa mid twentieth century.

Conservation work was undertaken on the keep about 1990. In advance of the conservation works excavation work was undertaken on behalf of the National Monuments branch of the Office of Public Works in July of 1989, revealing information concerning the construction of hall, details regarding the garderobe area, while precise details regarding an entrance building or gatehouse proved inconclusive.[xxxix]

A reception area and facilities to serve visitors were constructed within the castle grounds, near the entrance gate, as part of the on-site works at that time, while the keep was roofed and new floors inserted in the fabric. During these works an audio-visual presentation room was inserted at second floor level in the keep.

The restored roof showing timber peg joints.

[i] Sweetman, D., The Medieval Castles of Ireland, The Collins Press, Cork, in association with Dúchas, The Heritage Service, 1999, pp. 70-1.

[ii] Rynne, E., Meiler de Bermingham’s Tombstone, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 4, 1987, 1988, pp. 144-147; Leask, H.G., Irish Castles and Castellated Houses, Dundalgan Press (W. Tempest) Ltd., Dundalk, 1951, pp. 36-40.

[iii] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 1, 1912, pp. 201-221.

[iv] Sweetman, D., The Medieval Castles of Ireland, The Collins Press, Cork, in association with Dúchas, The Heritage Service, 1999, pp. 70-1.

[v] Waterman, D. M., Moylough Castle, Co. Galway, J.R.S.A.I., Vol. 86, No. 1 (1956), pp. 73-76.

[vi] Grose, F., Ledwich, E., The Antiquities of Ireland by Francis Grose, Esq., Vol. I., London, S. Hooper, 1791, pp. 65-66, plates 28, 29.

[vii] Waterman, D. M., Moylough Castle, Co. Galway, J.R.S.A.I., Vol. 86, No. 1 (1956), pp. 73-76.

[viii] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[ix] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[x] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[xi] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[xii] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[xiii] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[xiv] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 1, 1912, pp. 201-221.

[xv] Hardiman, J., A Chronological description of West or h-Iar Connaught, written A.D. 1684 by Roderick O Flaherty Esq., author of the ‘Ogygia’, edited from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College Dublin, with notes and illustrations, Dublin, Irish Archaeological Society, 1846, pp. 268-9.

[xvi] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p. 426.

[xvii] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p. 477.

[xviii] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p. 511.

[xix] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p. 534.

[xx] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p. 534.

[xxi] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth, 1574-1585, London, Longman, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1867, pp. 37, 42.

[xxii] Brewer, J.S. and Bullen, W. (ed.), Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, 1575-1588, London, Longman, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1868, pp. 46-52.

[xxiii] Hardiman, J., A Chronological description of West or h-Iar Connaught, written A.D. 1684 by Roderick O Flaherty Esq., author of the ‘Ogygia’, edited from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College Dublin, with notes and illustrations, Dublin, Irish Archaeological Society, 1846, pp. 268-9.

[xxiv] Hardiman, J., A Chronological description of West or h-Iar Connaught, written A.D. 1684 by Roderick O Flaherty Esq., author of the ‘Ogygia’, edited from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College Dublin, with notes and illustrations, Dublin, Irish Archaeological Society, 1846, pp. 268-9.

[xxv] Sir Henry Sidney’s Memoir of his Government of Ireland (continued), Ulster Journal of Archaeology, First series, Vol. 5 (1857), p. 313-4.

[xxvi] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth, 1574-1585, London, Longman, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1867, p. 270.

[xxvii] Annals of the Four Masters.

[xxviii] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of the State Papers relating to Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth 1574-1585, London, Longman, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1867, p. 371. While reference was made about March in a memorial for Malbie sent from the Privy Council to the Lord Deputy to a mitigation of the fine for the rebuilding of Athenry, the fine referred to in 1576 was 6,000l. and was at that time considered ‘too heavy’ by the Earl.

[xxix] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of the State Papers relating to Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth 1574-1585, London, Longman, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1867, p. 414. Letter dated 2nd December 1582; O Sullivan, M.D., Barnaby Googe: Provost-Marshal of Connaught 1582-1585, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 18, nos. i & ii, 1938, p. 22.

[xxx] Atkinson, E.G. (ed.), Calendar of the State papers of Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth, 1596, July –1597, December, preserved in the Public Records Office, Vol. VI, 1893, p. 218.

[xxxi] Atkinson, E.G. (ed.), Calendar of the State papers of Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth, 1 November 1600-31 July 1601, preserved in the Public Records Office, Vol. X, 1905, p. 219.

[xxxii] Mahaffy, R.P. (ed.), Calendar of the State papers of Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth, 1601-3 (with addenda 1565-1654) and of the Hanmer Papers, preserved in the Public Records Office, London, H.M. Stationary Office, 1912, p. 219.

[xxxiii] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[xxxiv] Grose, F., Ledwich, E., The Antiquities of Ireland by Francis Grose, Esq., Vol. I., London, S. Hooper, 1791, pp. 65-66, plates 28, 29.

[xxxv] Grose, F., Ledwich, E., The Antiquities of Ireland by Francis Grose, Esq., Vol. I., London, S. Hooper, 1791, pp. 65-66, plates 28, 29.

[xxxvi] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.

[xxxvii] Grose, F., Ledwich, E., The Antiquities of Ireland by Francis Grose, Esq., Vol. I., London, S. Hooper, 1791, pp. 65-66, plates 28, 29.

[xxxviii] Leask, H.G., Irish Castles and Castellated Houses, Dundalgan Press (W. Tempest) Ltd., Dundalk, 1951, pp. 36-40.

[xxxix] Papazian, C., Collins, B. and McCarthy, M., Excavations at Athenry Castle, Co. Galway, Cliona Papazian, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 43, 1991, pp. 1-45.