© Donal G. Burke 2013

Ireland is one of the few countries in the world in which the practical application of heraldry has been continuously regulated by a State-empowered authority since the mid sixteenth century. While heraldry proper was introduced into Ireland by the Anglo-Normans, a functioning regulatory authority or Office of Arms with jurisdiction over the entire island was only established under the Crown in 1552 in the person of the Ulster King of Arms. Despite momentous social and political upheavals since that date, that continuity was provided either by succeeding Ulster Kings of Arms under the Crown, a Principal Herald of Arms during the Cromwellian period, Ulster’s successor with jurisdiction in Northern Ireland; Norroy and Ulster King of Arms or Ulster’s successor in the Republic of Ireland, the Chief Herald of Ireland.

Despite some initial skepticism on both sides of the Irish Sea regarding the future of the Office of Arms following the transfer of responsibility for the Office from the Crown to the Irish State in the mid twentieth century, the Chief Herald of Ireland has continued the centuries-old service of granting and confirming arms to individuals, corporations and institutions, adapting the practical application of heraldry from the context of a monarch as the fons honorum to the context of an egalitarian democratic republic.

Having survived the transition from monarchy to republic, the Office of Arms has become one of the oldest offices, if not the oldest office, of the State in terms of continuity of service. As a working office rather than a museum, with its few officials drawing on a regular basis from genealogical and heraldic records amassed over four hundred years to serve those of Irish descent of diverse backgrounds across the modern world, the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland constitutes a unique and living part of the island’s cultural heritage.

Anglo-Norman families of east Galway

Although the Office of Arms under the Ulster King of Arms was founded in the mid sixteenth century, the use of heritable heraldic devices in Ireland, however, dates from the arrival of the Anglo-Normans over three and a half centuries earlier.

The Anglo-Normans, or, as they would later be known, the Old English, established themselves in Connacht on an organized basis from the early thirteenth century. Very few of the prominent names of Anglo-Norman origin that flourished in east Galway in the medieval period survive into the present. For the most part those who did survive include Burke (or de Burgh), Bermingham, Dolphin and Wall. Others such as Croke and de Cogan disappeared from the region in the aftermath of the Gaelic resurgence in the fourteenth century. Many, though not all, of those of Anglo-Norman descent bear arms often of simple geometric patterns or with a simple animal charge. In many cases the simplest pattern indicated the earliest date and are believed by many to have been initially simple to facilitate identification in battle or at tournament.

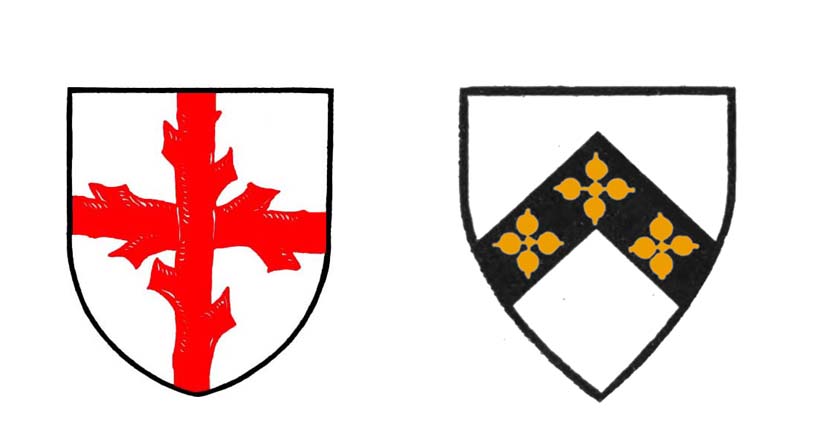

The shield of the Anglo-Norman Bermingham, Earl of Louth, killed in 1329 (left) and that attributed to ‘Lord Bermingham Baron Athenry’ (centre), after the tricked arms of Harl. Ms. 5866, dated circa 1606. The indented shield attributed to the Earl of Louth was elsewhere also attributed to the Bermingham Baron of Athenry, but shown dancettee and without the bordure (right).

Palesmen and Galway Merchants

Despite the absence of a herald or King of Arms resident in Ireland from the rise and decline of the Anglo-Norman colony until the mid sixteenth century, evidence of the usage of arms in Ireland in that intervening period survives, particularly on tombs and architectural work dating from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Arms of married couples shown impaled or with marks of cadency further display a knowledge of, and adherence to, the Laws of Arms as applied in England. The overwhelming majority of these relate to families of Old English origin long-established in regions with a close association with the Crown’s administration. Many within that number relate to families such as the FitzEustaces, Plunketts, Cruices, Cusacks or Flemings who held large estates in or about the Pale. Also included in that majority were a number of families prominent in trade or landholding in and about several important towns across the country with links to the Crown such as Galway. While many stone armorial plaques and features survive in that town from the seventeenth century, a number of carvings also survive from the fifteenth and early sixteenth century displaying arms borne by individuals of these families. Representatives of some of these families, such as the Blakes and Lynches acquired considerable estates about County Galway in and about the early decades of the seventeenth century.

Arms of an individual of the Lynches and an associated merchant’s or personal mark from the late fifteenth century Lynch tomb in St. Nicholas’ Collegiate Church in Galway.

Elizabethan, Seventeenth Century and Cromwellian arrivals

The arms of a number of those families who arrived in east Galway during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I or in the early seventeenth century also tended to reflect a simple pattern for the most part, as many were armigerous prior to that period or claimed descent from already armigerous families of Anglo-Norman or English origin, as opposed to bearing some of the more flamboyant or heavily-charged patterns of the newly rich of the Tudor period. Included among those families of Anglo-Norman or English origin but who arrived in east Galway in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century are the Brabazons of Ballinasloe, Dillons of Clonbrock, Lawrences of Ballymore and Lisreaghan and Moores of Cloghan. Others of Anglo-Norman origin such as the Arcedecknes of Clontuskert, Bellews of Mount Bellew and Nugents of Pallas and Flowerhill were transplanted to Connacht from elsewhere in Ireland or established in the area in the mid seventeenth century. The same principal applies in many cases to a number of those who acquired estates as a result of Cromwellian or Williamite confiscations in the seventeenth century, such as the Eyres of Eyrecourt. In such cases, these families are classified in the following pages from the date or period of their arrival in the east Galway region rather than the date of their arrival in Ireland. From a heraldic point of view, however, because of their common origin, the arms of many of these families often bear certain similarities to those settled in east Galway from the Anglo-Norman occupation.

The shield of Lawrence of Ballymore Castle and later of Lisreaghan (left), who arrived in the east Galway region in the Elizabethan period and the shield of Eyre of Eyrecourt (right) who arrived in the Cromwellian period in the mid seventeenth century.

Gaelic families

The bearing of a coat of arms was not initially part of the common heritage of those families of Gaelic descent. In general Gaelic Irish families adopted the use of arms sometime after the practice was in common usage among those of Anglo-Norman descent.

The power and authority of the Crown declined significantly in Ireland in the fourteenth and fifteenth century and it was only in the mid sixteenth century, under the Tudor monarchs, that the English Crown began to re-establish its authority and an effective administration in the west of Ireland. In 1552 a heraldic officer known as the Ulster King of Arms was established in Ireland with authority throughout the country over matters in that field. The Lord Deputy FitzWilliam wrote in 1562 that he conferred with the Ulster Herald regarding notes of the pedigrees of the O Neills and other families but referred to the ‘discountenance of heraldry’ among the Gaelic chieftains ‘and prevalence of rhymers, who set forth the most beastliest and odious parts of men’s doings.’[i]

In comparison with armigers of other origin in Ireland recorded in Ulster’s office from the mid sixteenth to the first years of the seventeenth century the number of those of Gaelic origin were few. Bartholomew Butler, the first Ulster King of Arms, served from 1552 to 1566. Of a sample of approximately twenty surviving entries in various forms in Ulster’s Registers dating from Butler’s term in office, none related to individuals of Gaelic origin.[ii] Almost all related to Palesmen, leading citizens and officials of the city of Dublin. A similar pattern, which also included senior clergymen of the new Reformed Church, was true of Butler’s successor as Ulster; Nicholas Narbon. Of a sample of approximately one hundred and thirty-six surviving entries dating from Narbon’s term between 1566 and 1588, only five could be said to possibly relate to secular individuals of Gaelic descent.[iii] That number comprised ‘Makcartie Earl of Clancart,’ (ie. Donal MacCarthy More 1st Earl of Clancare) Sir Bryan fitz Phelyme O Nele (ie. O Neill), Sir Charles O Carroll, Morertaghe oge Cavanaghe of Garkil and one Dermott of Dublin. With the exception of Dermott, whose origin is obscure (and may have been ‘Dermond’), all were previously chieftains or ‘Captains of their Name’ or leading representatives of some of the most important as opposed to minor Gaelic families and were associated for a time with the Dublin government. Nonetheless a small number of leading individuals of Gaelic descent are likely to have used or been granted arms by the Crown prior to the appointment of the first Ulster King of Arms. Some of these may date from at least the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century when the arms later associated with O Neill and MacCarthy More appear in a Continental Armorial at that time. Some may date from about the early 1540s, at which time a number accepted peerages and honours while agreeing to hold their lands of the Crown under the ‘Surrender and Re-grant’ policy of King Henry VIII. Among those small number of Gaelic leaders whose arms did appear in Ulster’s Register by the late sixteenth and earliest years of the seventeenth century were the O Brien Earl of Thomond, O Neill Earl of Tyrone, O Connor of Connacht, MacMahon, O Hanlon, McMurrough (ie. the head of the Kavanaghs) and MacCarthy More, the latter knighted in 1558 and created Earl of Clancare and Baron Valentia on his oath of allegiance to Queen Elizabeth I in 1565.

The case of Morertaghe oge Cavanaghe of Garkil (or Moriertagh oge Kavanagh of Garryhill, County Carlow) was an example of the lack of engagement with heraldry on the part of leading Gaelic families prior to the mid to late sixteenth century. In letters patent issued to Cavanaghe by Nicholas Narbon in late 1582 he referred to Cavanagh as chief of his name, gentleman and ‘descended of a great house undefamed.’ Despite the fact that it was asserted or assumed that Cavanaghe’s predecessors bore arms, Narbon stated that Cavanaghe, ‘being uncertayne under what sorte and manner his predecessors bore the said Armes,’ requested the Ulster King of Arms ‘to ordayne, assigne and set foorthe his Armes due and lawful to be borne.’ On foot of his application, Narbon ‘ordayned granted and set foorth’ heraldic arms to be borne by Moriertaghe oge and his posterity ‘to use and enjoye for evermore’ in a document which could be regarded as a grant or confirmation of arms dated 12th October 1582.[iv] Those arms were blazoned by Narbon as ‘quarterlie fower coates, the first gules a lyon rampant argent armed langued azure, the second vert a cross (a cross fourchee is here depicted) betweene six crosses crossletts fitches or, the third argent thre vipers 2,1 vert, the fourth azure three garbes 2,1 or.’

Morertaghe oge Cavanaghe and the Kavanaghs were descended from Donal ‘caomhánach’, killed in 1175, son of Diarmuid McMurrough alias Dermot na nGall, King of Leinster and their territory in the late medieval period lay in Counties Carlow and Wexford. Within that territory the lands of the branch to which Morertaghe oge belonged lay in the barony of Idrone in County Carlow. Born about 1516, Morertaghe oge had been a prominent member of the name throughout the mid sixteenth century and was approximately sixty-five years of age when arms were assigned him and his progeny. However, from Cavanaghe’s own admission and despite his mature years and position as chieftain of one of the foremost Gaelic families in Leinster, it is evident that armorial bearings of their chieftain or his immediate predecessors were unknown to him in 1582.

Ulster’s reference in the letters patent to Morertaghe oge’s descent of a family bearing arms would appear to have been more than a necessary social conceit, intended to provide in heraldic theory the Gaelic chieftain with the same historically-armigerous status as his Old English or New English peers. In the case of the Kavanaghs, it is possible that arms may have been assumed or used by some of Morertaghe oge’s immediate predecessors. A shield containing a lion passant above two crescents appeared on the seal of Donal reagh McMurrough Kavanagh, who styled himself ‘King of Leinster’, appended to a deed of 1475. The same seal, still bearing Donal reagh’s name, was later used by his grandson Murrough, appended to a document dated 1525.[v] This is a rare example of a surviving seal of a Gaelic king or chieftain displaying an armorial shield. Devices found on a number of early Gaelic seals do not appear to have been intended as heritable devices but it is possible in the case of the Kavanaghs that the lion may have been assumed by the users as such and may have given rise to its use on later arms. In addition, at least one other of the name, Cahir mcArt Kavanagh, had submitted to the Lord Deputy in 1550 and in 1554 had been created for the duration of his lifetime Baron of Ballyan. He died shortly thereafter, however, and it is uncertain if he was granted or confirmed arms by Ulster. (It should be noted that arms were associated with ‘McMurrough’, the Gaelic title of the head of the Kavanaghs in one of Ulster’s registers dating from about the late sixteenth century. Those arms may therefore date from about the time of Morertaghe oge and possibly earlier. These would have been roughly contemporaneous with Morertaghe oge’s patent and variations of two of these are found in the quarterly arms of Morertaghe oge; ‘Gules a lion rampant Or’ attributed to ‘McMurogho’ and ‘Sable three garbes 2,1 Argent’ attributed to ‘Dermond McMurgh King of Leinster in the time of Henry II.’ Although incorporated into the arms of Morertaghe oge, it is unlikely that Dermot McMurrough King of Leinster ever bore heraldic arms, having died circa 1171 and these are almost certainly a later attribution.) Irrespective of whether another of the name bore arms unknown to Morertaghe oge in the mid sixteenth century, it is clear that Morertaghe oge did not make use of arms prior to 1582 and his application for the same to the Office of Arms in Dublin is, in addition, further evidence of the fact that the Ulster King of Arms was the only heraldic authority in the country with whom those of all traditions, whether Old English, New English or Gaelic, came to engage.

The absence of arms of many Gaelic families in the earliest surviving of Ulster’s records, taken together with comments made by the eminent English antiquary Sir Henry Spelman at the end of the sixteenth century, would lend further credence to the Lord Deputy’s comments mid-century regarding the Gaelic chieftain’s general antipathy towards heraldry at that time. Writing sometime about 1595 in his Latin treatise on the subject of heraldry, entitled ‘Aspilogia’, Spelman noted that Ireland in earlier times had closely resembled or ‘been the image of’ England with regard to heraldry but at the time of his writing many of the noblest and foremost families of Ireland were without heraldic arms.[vi]

Spelman’s remarks imply that the prominent families to whom he made reference were without arms as opposed to simply not having had their arms recorded in the office of the Ulster King of Arms. Spelman did not expand upon his remarks as to whether those families without arms were of Anglo-Norman, New English or Gaelic origin. However, given the predominance of armigerous families of Anglo-Norman origin of the first rank, together with those of middle rank of the Pale or of New English origin in the earliest records of Ulster’s office from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, it would suggest that many of those to whom Spelman referred included some of the senior-most Gaelic families.

The arms of the Gaelic families were not originally intended to be borne on a shield in battle and the need for simplicity to facilitate ease of recognition on that field was not paramount. Gaelic lords, however, did use heraldic devices for identification on seals in their legal transactions with the colonists and between themselves from a relatively early period. The arms of Gaelic families tend to feature charges of an anatomical, botanical or a zoological nature placed on a field and, while certain of those arms borne by Gaelic families could be simple of design, such as those of O Conor Don of Connacht, on occasion the combination of such charges could be erratic and busier than that employed by the earliest Anglo-Norman armigers.

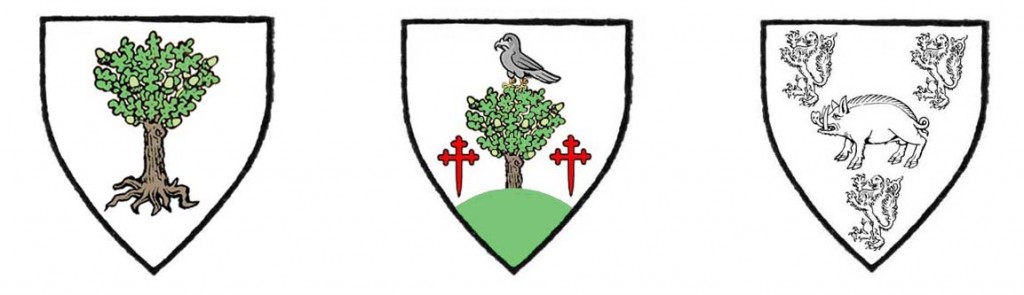

The shields of O Conor Don (left), Concanon (centre) and the untinctured shield of Ward (right), families of ancient origin in east Galway.

The extension of the use of heraldic arms

For the greater part of its history, Ireland, like elsewhere in Europe, possessed a socially-stratified society. The upper echelons of medieval Irish society was composed of those of Native Irish origin and those of Anglo-Norman origin, the latter whose ancestors arrived in Ireland in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries. Like their Gaelic counterparts, those of Anglo-Norman origin who remained within the sphere of influence of the English Crown laid claim to their social standing based upon their pedigrees. Hand in hand with the Anglo-Norman’s claim to exalted ancestry and position was associated his claim to bear the heraldic arms of his predecessors. However, unlike their Anglo-Norman counterparts, no such claim to arms would appear to have been made by the medieval Gaelic aristocracy, as heraldry did not form part of their culture until a later period.

With the increase in power of the English Crown in Ireland and the granting of titles and lands to be held under English law to a number of prominent Gaelic chieftains in the sixteenth century, this would appear to have altered. Arms were recorded in Ulster’s office for several such Gaelic lords from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, but the number of such individuals were few. However, following the more general and widespread acceptance of English laws of inheritance and the recognition of the authority of the English Crown by the broad mass of the landed classes of Ireland in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the right to bear heraldic arms became an important social indicator among those who composed the ‘gentry’ or upper classes of Ireland, whether of Old English, New English or Gaelic origin, and it was taken that anyone of the social rank of gentleman or greater, bore or was entitled to bear, a coat of arms.

It should be noted that not all senior representatives of families of Gaelic, Anglo-Norman or English origin were armigerous and heraldic arms were not associated with many Irish families, particularly those of minor landowning status by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, not all arms borne or claimed by senior representatives of families were officially recorded in the office of the Ulster King of Arms or in certain cases such records may not have survived. Examples of such cases within and about east Galway include the Colohans, Wards and Larkins, all of ancient origin in that region and the senior-most members of whom were all minor landed proprietors in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The only evidence that arms were used or claimed by the Colohans of Cogran and Ashgrove in King’s County is the description of those arms in a letter written in 1842 to the antiquary John O Donovan by an old acquaintance familiar with the family. Of the Wards of Ballymacward, the only physical evidence of their bearing or assuming arms is the survival of an armorial headstone in the ruins of the Franciscan friary at Kilconnell. In a like manner, there is no evidence of officially registered arms in the records of the Ulster King of Arms relating to representatives of the Lorcan or Larkin family of east Galway but evidence of their use of armorial bearings is found on an eighteenth century armorial headstone in the grounds of the Lorcan chapel at the Franciscan friary at Meelick. These are the only known surviving evidence of certain members of these families having claimed arms and, in the latter two cases, had these headstones not survived, there would be no proof that arms were ever associated with these families. The same situation was not restricted to those of Gaelic or native Irish origin, and, prior to a confirmation of arms granted to one of the name in the early 1940s, the only surviving public evidence of senior members of the Pelly family of east Galway bearing arms was a badly eroded eighteenth century armorial headstone in Portumna priory.

The armorial headstone relating to Anthony Lorcan who died in 1744 and members of his family in the ruins of the Lorcan family chapel at Meelick in County Galway, the only evidence of senior members of this family using armorial bearings.

The recording and regulation of arms from the sixteenth century

With the re-assertion of Crown influence and power in the sixteenth century came a greater regulation of heraldry and a more assiduous recording of pedigrees and arms of the most prominent Irish houses.

As part of its remit, the office of the Ulster King of Arms was involved from about the late sixteenth century in the ceremonies relating to the funerals of a significant number of individuals of the more socially prominent families. A decree of 1627 made the recording of the death of an armiger obligatory and the deceased’s heir or executor was required to submit details to Ulster King of Arms. This may have contributed to the familiarity of some of those families with the representation of such details as the differencing of arms between brothers within the same family and the correct achievement to have carved on memorial stone tablets at their ancestral burial places, particularly in the seventeenth century.

Details and arms were recorded in the ‘Funeral Entries’ of the Office of the Ulster King of Arms from early in the seventeenth century for members of such families as the O Kellys, Burkes, Brabazons and later for Eyres among others, suggesting the involvement of heraldic officials in those funeral arrangements. The involvement of the office, being often costly, may have also been a contributing factor in the lack of involvement of heraldic officials in the funerals of those of lesser social standing or of lesser means.[vii]

An example of a high status funeral in the region involving officials of the office of the Ulster King of Arms was that of the Rt. Hon. John Burke, Viscount Clanmorris, a younger son of the Earl of Clanricarde. In recording the arms, offspring and marriage details of Viscount Clanmorris, who died in November of 1633, Albone Leverett, then Athlone Pursuivant (a junior Officer of Arms), noted that ‘he was interred with funeral Achivements belonging to his degree the xvii of December in the Abbey of Athenry.’[viii] Likewise, in the following century, Ulster’s office recorded the death at his residence on Fleet Street, Dublin, of Colonel Melaghlin Donolan, senior-most member of the Donolans of Ballydonnellan in east Galway and his burial in November of 1726. Both he and his father, Colonel John Donolan, who died in 1710, were recorded in the office’s ‘Funeral Entries’ as having been buried ‘with Escocheons.’[ix]

In England, an extensive series of visitations of the various regions by heralds in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries sought to ensure that all of those claiming arms were entitled to do so. Those whose arms had not hitherto been officially recorded in the herald’s registers could seek a confirmation of their right to those arms if it were found that they were entitled to do so by descent from a previous armiger or by previous grant. In Ireland there were few visitations undertaken as a result of the social and political unrest throughout that same period and the possibility arose that many who bore or claimed arms were not recorded in Ulster’s Register. As a result of this and other related factors, the Crown extended the right to the Ulster King of Arms to issue a confirmation of arms to a petitioner, if that petitioner could prove long use of those arms by several generations of his family over an extended period. The loss of an amount of Ulster’s records both in the late seventeenth century and at later periods ensured that this facility remained not only a feature of Ulster’s practice into the twentieth century but also of that of his successor; the Chief Herald of Ireland.

The historical implications of the right to bear heraldic arms

Given the hereditary nature of heraldry, genealogy and heraldry have been intimately intertwined, with any claim of entitlement to bear arms, other than a new grant of arms, based upon genealogical proof of descent from an armiger (ie. one bearing, or entitled to bear, heraldic arms). An example of the importance of genealogical proof of noble ancestry and the entitlement to heraldic arms in the early modern period is found in experience of many of the Irish Jacobite émigrés who left Ireland in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The great majority were supporters of the Roman Catholic King James II who was deposed in favour of his daughter Mary and her Protestant husband William of Orange. Most settled on the Continent in the realms of the Catholic monarchs of France or Spain. There they were dependant on the provision of a certified pedigree or statement confirming their noble status in order to achieve high rank or advancement in the army and at Court. The deposed King James II appointed John Terry as Athlone Pursuivant or herald to the Stuart Court in exile in France and it was Terry to whom many émigrés would apply for pedigrees and arms. In his work, however, Terry would liaise where necessary with the Ulster King of Arms in Dublin or with heralds in England or Scotland, who derived their authority ultimately from the Royal House which displaced the Stuarts. Following Terry’s death the descendants of those Irishmen or their countrymen newly arrived on the Continent later in the eighteenth century would continue to apply to the Ulster King of Arms in Dublin in relation to genealogical and heraldic matters, irrespective of the political differences of their respective monarchs, to establish their claim to gentility in their newly adopted countries.

The equation of rank or social status with the bearing of heraldic arms continued into the twentieth century, with one of the last of the Irish R.M.s (Resident Magistrates) writing in the mid-twentieth century on the subject of heraldry that ‘arms-bearing is the official insignia of ‘gentility’ and anybody who is armigerous is ipso facto an official ‘gentleman’ without any regard to his birth or even to his manners at table.’[x] This is held to be the case into the early twenty-first century in such jurisdictions as those of the English College of Arms and the Scottish Lord Lyon King of Arms.[xi] However, a grant of arms by a lawful authority in those jurisdictions or a grant or confirmation of arms by the former Ulster King of Arms is regarded by many commentators not as a creator of ‘gentle’ rank or ‘gentility’ in itself but rather a signifier or acknowledgement of ‘gentle rank,’ given that a heraldic authority does not have the power to ennoble. In the words of John Philip Brooke-Little, then Norroy and Ulster King of Arms, “while some few grants read like patents of gentility, the vast majority read as they are intended to be understood, namely as recognitions of existing gentility.”[xii]

Sir Nevile Wilkinson, the last Ulster King of Arms, died in 1940 and the office was continued by Thomas Ulick Sadleir as Acting Ulster King of Arms until 1943. In that year heraldic responsibility for what would be the Republic of Ireland passed to the Irish State’s Genealogical Officer (later known as the Chief Herald of Ireland) who succeeded to many of the functions and powers of the Ulster King of Arms. The regulation of heraldry had previously been maintained in Ireland in the absence of the monarchy during the Interregnum, when the Cromwellian authorities had appointed one Richard Carney to the position of Principal Herald of Arms for the whole dominion of Ireland with grants issued under letters patent of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. (The post of Ulster King of Arms was resumed after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660). Likewise, the practice of heraldry continued in the Republic of Venice in the absence of monarchy under the elected Doges and, after the establishment of the new Irish Free State and later the Republic of Ireland, heraldry continued to be regulated by the State. While the title of ‘Ulster’ was attached to the existing post of the ‘Norroy King of Arms’, a member of the English College of Arms to whom was transferred jurisdiction over Northern Ireland, the Chief Herald of Ireland became the State authority on all heraldic matters relating to the Republic of Ireland.

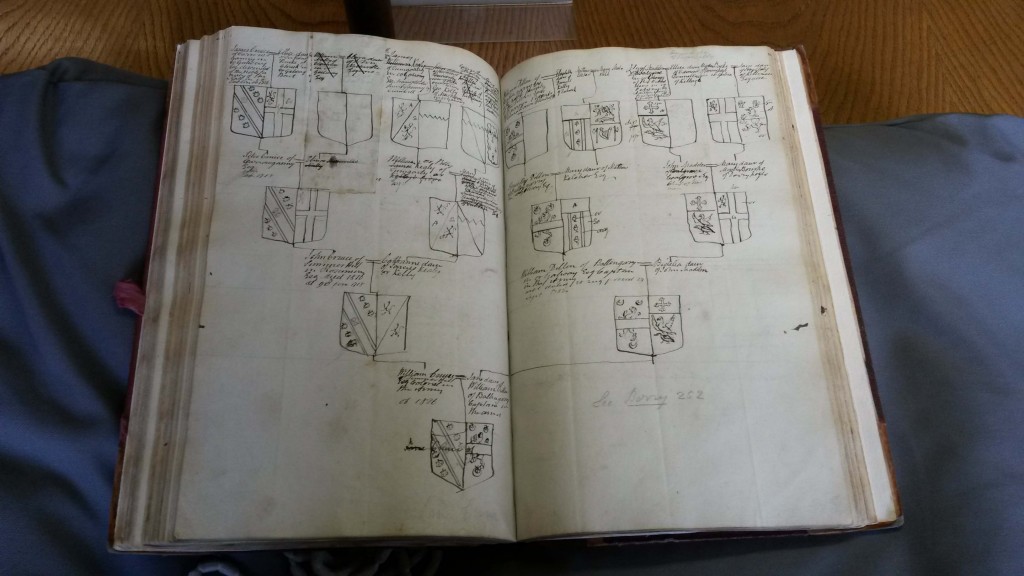

An armorial pedigree depicting the arms over several generations of the ancestors of Colonel William Cruice of Summer Hill, Co. Roscommon, who died in 1826, and his wife, Jane Dillon, in Genealogical Office Manuscript No. 205, part of the genealogical and heraldic records of the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland, formerly those of the Ulster King of Arms. © N.L.I., Dublin, Genealogical Office.

The Chief Herald of Ireland, as the repository of the original records of the Ulster King of Arms and the inheritor of most of Ulster’s functions in the Republic of Ireland, provided continuity as heraldic successor to Ulster in the Republic from the mid twentieth century. The practice of heraldry by the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland involves as part of its work the granting or confirmation of arms within the particular tradition and customs that have been handed down through succeeding Ulster Kings of Arms and Chief Heralds of Ireland since the mid sixteenth century, tempered to reflect the constitutional and societal changes that occur in modern Ireland. As the Constitution of Ireland states that all citizens are equal before the law and that titles of nobility shall not be conferred by the State, a grant or confirmation of arms by the Chief Herald of Ireland, as the State’s heraldic authority, cannot be said to confer any social rank upon, or ennoble, the recipient of any such grant or confirmation.

In keeping with the constitution of the Republic, which guarantees equality between genders, the State’s heraldic authority makes no differentiation between male and female offspring of armigers in relation to marks of cadency. In certain other jurisdictions only male offspring utilize these standardized symbols to identify their place in the order of birth of offspring of armigers, ie. eldest, second, third sons, etc., thus distinguishing one individual’s arms from another within the same immediate family. The office of the Chief Herald recognizes in its practice all children, male and female, in applying marks of cadency.

With regard to female armigers, the Chief Herald of Ireland has granted arms to ladies with shield, helmet and crest from the late twentieth century. Prior to that period, in common with most lawful heraldic authorities, the arms of ladies had, for the most part, been exemplified on lozenges, without helmet or crest, on the basis that ladies traditionally would not have borne military accoutrements of that nature. From about the late 1990s the Chief Herald has granted arms to ladies with shield, helmet and crest, recognizing the role that may now be played in the modern period by women in the military field.

In keeping with other modern societal changes, the Chief Herald of Ireland does not make any distinction between armigers, or children of armigers, born within or without marriage. The practice has altered from that employed by the Ulster King of Arms, who, in keeping with then common practice, applied brisures or identifying marks to denote illegitimacy. An example of the former approach taken was the confirmation of arms granted in 1895 by Arthur Vicars, Ulster King of Arms, to Frederick James Eyre, gentleman, of North Adelaide, ‘in the colony of South Australia’ and his descendants with a shield exhibiting a bordure wavy and a crest debruised with a baton sinister. Both marks denoted descent from his father Thomas Eyre of St. Helier on the Island of Jersey, who was a natural son of Thomas Eyre, formerly of the town and parish of Eyrecourt, County Galway, ‘Brigadier-General of the South American Patriotic Forces in the American War of Independence and sometime Captain of the Fifty-first Regiment of Foot in the British Army.’[xiii]

The former Kildare Street Club on Kildare Street, Dublin, home to the Genealogical Office and the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland since 1987, following its relocation from Dublin Castle.

The right to bear a coat of arms

As heraldry, as it came to be regulated in Ireland, had its origins in the Anglo-Norman period, the general rule in England is applicable in Ireland that a coat of arms is the property of one individual and not all members of the same name. That coat of arms is then inherited by the eldest son of the armiger. Other descendants of the original armiger who can prove a direct line of descent from the armiger are entitled to bear the arms, but with a variation approved by the correct heraldic authority to differentiate their arms from those of the senior representative of the family. A common error is the mistaken belief that there exists an automatic right to a specific coat of arms on the part of a person bearing the same surname as another properly entitled to bear that same coat of arms. The concept of one coat of arms that belongs automatically to everyone of the same surname or extended group has no basis in heraldic law in Ireland.

An unfortunate practice developed in the modern period whereby many purveyors of images of arms have attributed arms to customers that by right belong to the senior member of one particular family, on the incorrect assumption that all those bearing the same name (or in some cases an unconnected but similar name) are entitled to bear those arms. In Ireland, the Chief Herald of Ireland ‘retains and exercises the right to regulate the use of arms.’

Sept Arms

With regard to the regulation of the use of arms in Ireland, much confusion arose in particular in relation to what became known in the mid twentieth century as ‘sept arms.’ Dr. Edward MacLysaght, first Chief Herald of Ireland and Genealogical Officer, in the introduction to his 1957 publication of ‘Irish Families, their Names, Arms and Origins’ elaborated on his theory of ‘sept arms.’ (A sept could be taken as a family group of people all bearing the same name, originating in the same place and descended from a common ancestor.) MacLysaght’s theory advocated the notion that all those bearing certain surnames in Ireland, if it could be taken that they were of the same sept and if a coat of arms was associated with a prominent line of that same sept, were entitled to a ‘proprietorial interest’ in those same arms. They could, he suggested, display the same arms without impropriety. His theory could be read as directly contradicting the conventionally accepted laws of heraldry in Ireland and Great Britain by which those arms categorized by him as ‘sept arms’ were more properly those to which the senior-most representative descended from the original armiger was solely entitled.

The widespread popularity of MacLysaght’s publication facilitated the dissemination of his remarks regarding ‘sept arms’ both in Ireland and abroad and contributed in no small part to the misapprehension by many that the laws of heraldry as practiced in Ireland allowed for individuals of the same sept to bear the same arms. However, MacLysaght appears to have recognized a subtle distinction between what he described as a ‘proprietorial interest’ and the actual right to bear heraldic arms and, while he qualified his remarks in the same work by stating that, for a person to bear arms ‘in the true heraldic sense,’ a confirmation or grant of arms from the Chief Herald of Ireland was necessary, much confusion arose. MacLysaght’s remarks were used by some to claim the right to bear arms that were more correctly the property of others.

MacLysaght provided blazons and illustrations of the arms which he suggested could be taken as ‘sept arms’ and could be ‘displayed’ by those of the name believed to be of the same sept. An example of the erroneous approach taken would be the assumption by those of the surname Fitzgerald that all individuals of that ‘sept’ were entitled to bear the arms illustrated as the pronominal or ‘Great Arms’ of the name. MacLysaght’s work gave the ‘sept arms’ associated with the surname Fitzgerald as ‘Argent, a saltire Gules,’ the undifferenced shield which from the medieval period has formed the basis of the heraldic birthright of the Fitzgerald Earls of Kildare and later Dukes of Leinster.

Difficulties arise with certain of the arms given as ‘sept arms’ in ‘Irish Families’ in relation to their previous assignment by heraldic authorities to identifiable individuals and their descendants. One such case is the arms shown by Dr. MacLysaght as the ‘sept arms’ of O Coffey of County Cork. At least three separate and distinct families of Coffeys of Native Irish origin existed; one established in County Cork, one in the east of County Galway and one in the midlands of Ireland. MacLysaght blazoned the ‘sept arms’ of O Coffey of County Cork as ‘Vert, a fess Ermine between three corns or Irish cups Or’ with a crest of ‘a man riding a dolphin Proper.’ Those same arms, however, were confirmed in 1684 by his predecessor Sir Richard Carney, Ulster King of Arms, as appertaining to Reverend Thomas Coffy of Lynally in King’s County and his posterity, each ‘bearing their due difference according to ye law of Armes.’ The subject of the confirmation was a native of Ireland, who, having been a scholar at Trinity College Dublin in 1638, served as Master of the Free School in Dublin in the early 1640s and Anglican Minister of Finglas in 1654. The incumbent of Lynally since at least 1665, he died as Vicar of Fercall in March of 1690 and was buried at Lynally. His memorial there described him as ‘Thomas Coffy, Clearke, Master in Arts of Trinity Colledge Dublin, Vicar of Fercall and one of His Majestie’s Charles II Justices of the Peace in the King’s County.’[xiv] The only difference between the arms confirmed upon Rev. Thomas Coffy and his heirs and those attributed by Dr. MacLysaght as the sept arms of O Coffey of County Cork lay in a motto having been assigned to the former. However, that minor difference was of no significance as mottos are not regarded as an heritable element in Irish armory.

If MacLysaght’s theory was to be read as implying that anyone of the name O Neill whose family originated in County Tyrone was entitled to bear the arms given by MacLysaght as the sept arms of O Neill, it would be in disregard of the fact that the same shield but with crest and motto was confirmed in 1918 by George Dames Burtchaell, Deputy Ulster King of Arms, unto Francisco de Assis Enrique Jose Maria Federico Luciano Maria del Rosario del Santissimo Sacramento Iveson y O Neale of the Kingdom of Spain and the other descendants of his ancestor James O Neale of Roscrea, County Tipperary who flourished in the late seventeenth century, each to exhibit on their respective individual arms ‘their due and proper differences.’ In granting the 1918 Confirmation of Arms, the Deputy Ulster King of Arms recognised that King Charles III of Spain had authorised the same family of O Neale to use these arms by warrant dated 1776, and Deputy Ulster issued the confirmation with the usual provision that these arms were to be borne solely by the armigers of this particular line ‘for ever’ ‘according to the laws of Arms and without the let, hindrance, molestation, interruption, controlment or challenge of any manner of person or persons whatsoever.’[xv] The same could be said for many of those arms described as ‘sept arms’ in that same publication.

In his 1957 publication Dr. MacLysaght associated those of the surname Keating with sept arms of ‘Argent a saltire Gules between four nettles leaves Vert,’ with a crest of ‘a boar statant Gules armed and ungled Or holding in the mouth a nettle leaf Vert.’ Fourteen years earlier, however, on the last day of March of 1943, Thomas Ulick Sadleir, Acting Ulster King of Arms, had certified that the same shield and crest did ‘by right belong and appertain unto Reginald Keatinge of Howth, County Dublin, Esq., O.B.E., Honorary Serving Brother of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem in England, J.P., Co. Dublin, descended from Oliver Keating of Kilcoan in the County of Wexford, Esq., whose Arms and Pedigree were recorded in this office in 1618, and his descendants, observing and using their due and proper differences according to the Laws of Arms.’[xvi]

Similarly, it is important to note that, from the context of the social system within which Gaelic society existed before and immediately after the establishment of Ulster’s office, there was no question of every member of the same sept being entitled to display heraldic arms. Not only would it have been contrary to the Laws of Arms in Ireland and England in the sixteenth century and thereafter, but, given the hierarchical structure of Native Irish society and the wide social range, from lord to labourer, across which all those of the same sept would fall, it would have been inconceivable that any of that name of a social rank less than gentleman or its equivalent could without impropriety even ‘display’ arms at that time.

In addition to MacLysaght’s own qualification regarding ‘sept arms’ and the bearing of arms in the ‘true heraldic sense,’ his theory regarding ‘sept arms’ was not, and is not, accepted by his successors to the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland, the State’s authority on all heraldic matters related to Ireland.

The Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland states that ‘in Ireland one is only entitled to bear a coat of arms if;

- One has proven descent from an armiger whose arms are registered in the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland, has satisfied the Chief Herald as to one’s position in the scheme of cadency (ie. system of symbols to distinguish between otherwise identical arms within the same family) and thereafter issued with a certificate of arms, including such differences as required, or

- One has been confirmed arms by the Chief Herald of Ireland, exhibiting any distinctions deemed appropriate by the Chief Herald, where the armiger has shown by a high standard of proof that the same arms were used by three generations of the family or at least one hundred years, or

- One is granted arms by the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland.’

A grant of arms may also be made with a special remainder ‘so that, depending on the terms, arms may also be enjoyed by the collateral descendants of a common male ancestor.’ An example of this is an instance where a grant of arms is made to one individual and his descendants and simultaneously to a brother of that same individual and his posterity as the descendants of their father as the common ancestor, each to bear their respective arms with due and proper differences.

The Republic of Ireland is one of the few countries in the world to have retained a State-authorized regulated heraldic authority to which a petition for a grant or confirmation of arms may be addressed. Those to whom arms may be granted by the Chief Herald of Ireland consist of;

- a citizen of Ireland or an individual who has an entitlement to become a citizen.

- a person resident in the State for at least the five year period immediately before the date of the application for a grant of arms.

- a public or local authority, corporate body or other entity which has been located or functioning in Ireland for at least five years.

- an individual, corporate body or other entity not resident or located in Ireland but who or which has substantial historical, cultural, educational, financial or ancestral connections with Ireland.

According to the National Library of Ireland, the response of the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland to the continuing ‘tradition of the Irish abroad seeking grants of arms from home, is the expression of the Nation’s “special affinity with those of Irish ancestry living abroad who share its cultural identity and heritage’, as set out in Bunreacht na hÉireann, or the Constitution of Ireland.’[xvii]

Issued in the name of the Irish State by one of the oldest surviving cultural institutions in the country, a grant or confirmation of arms from the Chief Herald of Ireland serves as an enduring heritable manifestation of the common bond between the original grantee and his or her descendants, between all descendants of the grantee and of the bond between those same descendants and their country of origin. The same grant, reflecting the centuries-old customs and traditions that constitute the Laws of Arms, recognizes the grantee and his or her family within that context as a share-holder in the cultural heritage of the island in a unique and particular way, adding their personal history to those of countless armigers of Ireland whose arms have been entered in the same Register of Arms since the middle of the sixteenth century.

[i] Hamilton, H.C., (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p. 191.

[ii] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 422, Vol. I.

[iii] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 422, Vol. I; Crawford, J. G., Anglicizing the Government of Ireland, Irish Academic Press in association with The Irish legal History Society, Dublin, 1993, p. 456. The arms of John Garvey, Dean of Christ Church in Dublin were also included among the entries dating from Narbon’s period as Ulster King of Arms. Born in Kilkenny, he was the eldest son of John O Garvey of Murrisk, County Mayo. Educated at Oxford he held various offices before becoming a prebendary of St. Patrick’s, Dublin in 1560. He became dean of Christ Church in 1565 and later became a member of the Irish Privy Council. He was appointed Bishop of Kilmore in 1585 and Archbishop of Armagh four years later. He died in 1595.

[iv] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 422, Vol. I, p. 2; NLI Dublin, n2805, p. 1707, Denization of Oneale, etc. The division of all the septs of the Kevanaghes. Patent given to Mortogh oge O Kevanaghe for bearing a coat of arms; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Elegy on the death of the Rev. Edmond Kavanagh by Rev. James O Lalor, Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society, Vol. I, 2nd Series, 1856-1857, pp. 118-143; Cal. State Papers, Eliz I, 1574-1585, pp. 310, 409; Cal. State Papers, Eliz. I,1586-1588, pp. 288-9. According to O Donovan, Narbon Ulster blazoned Cavanaghe’s arms on the grant or confirmation of 1582 as ‘quarterlie fower coates, the first gules a lyon rampant argent armed langued azure, the second vert a cross (a cross fourchee is here depicted) betweene six crosses crossletts fitches or, the third argent thre vipers 2,1 vert, the fourth azure three garbes 2,1 or.’ Henry Sheffield of County Carlow, writing to Lord Burghley in March 1587, described Morertaghe oge as a man of seventy years of age and chief of the Kavanaghs when he was murdered in November of the previous year by Henry Heron and his men on the pretext of four cows having been stolen. Sheffield attributed Heron’s actions in part to the grudge held against the Kavanaghs by Heron’s brother-in-law Dudley Bagenal. As a result two of Morertaghe oge’s sons and their men ambushed Bagenal in March of 1587 and killed him.

It should be noted that G.O. Ms. 84 Draft Grants c. 1580-1690 gives arms from ‘McMorogho’ of ‘Gules a lion rampant Or’ and ‘Azure three crescents Or’ were given therein for ‘the King of Leinster.’ (Most other late sixteenth century and early seventeenth century records of Ulster’s office give the lion rampant of ‘McMorogho’ as Argent) Also included in that same manuscript was a depiction of the arms of ‘Dermond mcMurgh, King of Leinster in the time of Henry II’ tricked ‘Sable three garbs 2 and 1, Argent.’ Those entries appear to date from the late sixteenth century but are believed to date from approximately 1580 at the earliest. The arms of ‘McMorogho’ ie. McMurrough, the chieftain of the Kavanaghs, bears a close resemblance to the first quarter in Morertaghe oge’s arms. In other later Registers from Ulster’s Office the arms of ‘Mack Murough’ were shown as ‘Argent a lion passant and two crescents in base Gules.’ An example of such an entry occurs in G.O. Ms. 61, Irish Arms ‘B’. The entries therein appear to have been compiled c. 1650 but many of its Irish arms are evidently derived from older manuscripts in Ulster’s office such as Funeral Entries from earlier in the century. An entry also occurs in G.O. Ms. 61 for ‘Dermot fitzDerbynangall King of Leinster.’ Dermot fitz Derbynangall or Dermot son of Dermot na nGall was attributed there arms of ‘Sable a lion rampant Gules armed and langued Or.’ While again similar to those of Morertaghe oge, this individual would have flourished in the late twelfth century as was unlikely to have borne arms at that time. The same mid seventeenth century register gave the arms of ‘Cavanagh’ as ‘Vert a cross moline between eight crosses crosslet fitchee.’ The arms of ‘Idrone’ but as a family name ‘Odrone in the County of Catherloyh’ as also depicted separately in the same manuscript as ‘Argent three vipers coiled Vert.’ This same error also occurred in G.O. Ms. 98. Entitled ‘Irish Arms – Smith Rouge Dragon 1613,’ this manuscript bears the date of 1613 and the name of William Smith who held the office of Rouge Dragon Pursuivant of Arms in Ordinary at the English College of Arms from 1597 to 1618. It depicted the same three coiled vipers Vert on a shield Argent as the arms of ‘Odrone, Baron of Odrone.’

William Smith’s 1613 compilation of Irish Arms to a great extent reflect other near contemporary armorial registers from Ulster’s office in the same small number of family names of Gaelic origin which occur. These consisted of the bearings of; ‘Camok O Neale Erle of Tirone, Hugh O Neale Erle of Tirone, Tirlow Obryan Erle of Tomond, Mack-more Erle of Glencar (ie. MacCarthy More Earl of Clancare), Odrone Baron of Odrone, Bryan, Sir Barnaby Fitzpatrick, Mac-Artimore (MacCarthy More), Mac Marhoo (ie. McMurrough), Mack Marhow (ie. MacMahon), possibly ‘Madane,’ Lord Ossory (ie. Fitzpatrick Baron Upper Ossory), O Noyle, O Neale, O Brian, O Brian, (two different bearings), O Conehoo (ie. O Connor) and O Henleyne (ie. O Hanlon). This amounts to a maximum of eighteen coloured shields out of a total of three hundred and thirty-five coloured shields. (The arms of Bryan are included with those of Gaelic origin as they appear quartered in the arms of the Earl of Thomond but their origin as arms are more likely to have been Anglo-Norman. Those of ‘Ogan’ bear a close resemblance to those of Wogan of Rathcoffey, given in ‘Irish Arms B,’ and if this surname was intended as ‘Wogan’ their origin would also have been Anglo-Norman.) The number of Gaelic surnames involved amounted to a maximum of ten. The compilation is non-exhaustive as it does not include individuals such as Sir Brian O Rourke, executed in 1591, whose arms appear in other contemporary armorials but the small number of Gaelic arms in relation to the arms of those of other origin corresponds to a number of other contemporary armorial manuscripts that once formed part of Ulster’s records.

[v] Graves, J., Original Documents of the MacMurroughs, Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Society of Ireland, 4th Series, Vol. 6, No. 53, Jan. 1883, pp. 22-36; Curtis, E., Some Further Medieaval Seals out of the Ormond Archives, including that of Donal Reagh MacMurrough Kavanagh, King of Leinster, JRSAI, 7th Series, Vol. 7, No. 1, June 1937, pp. 72-76.

[vi] ‘Et in Hybernia (quae antiquioris Angliae imago est) plurimi habentur nobiles è primariis families, etiam nunc dierum asymboli.’ Spelman, H., Aspilogia, in Bysshe, E. (ed.), De Studio Militari by Nicholas Upton, Tractatus de Armis by John de Bado Aureo and Aspilogia by Henry Spelman, Roger Norton, London, 1654, p. 51; Sitwell, Sir G. R., The English Gentleman, The Ancestor, No. 1, April 1902, Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd., Westminster, 1902, p. 80; Keen, M., Origins of the English Gentlemen, Tempus Publishing Ltd., Stroud, 2002, p. 72. In ‘Aspilogia’, Spelman also remarked that many notable or ‘not ignoble’ families of England were without heraldic arms prior to the time of King Henry VI, whose reign began in 1422.

[vii] Ó Comáin, M., ‘The Poolbeg Book of Irish Heraldry’, Poolbeg Press, Dublin, 1991, p. 57.

[viii] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 64-79 Funeral Entries (Ms. 68, p.13)

[ix] NLI, Dublin, G.O., Ms. 79 Funeral Entries, Vol. 17 c. 1619-1729, pp. 237, 254; O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 172.

[x] Sir Christopher Lynch-Robinson, Bt. and Adrian Lynch-Robinson, Intelligible Heraldry, Macdonald & Co., London, 1948, p. 114.

[xi] Franklyn, J., Shield and Crest, an account of the art and science of heraldry, MacGibbon & Kee, London, 1967, p. 2; Fox-Davies, A.C., The Right to bear arms, by ‘x,’ London, Elliot Stock, 1900, 2nd edition, p. 32. ‘Nothing a man can do or say can make him a gentleman without formal letters of gentility – in other words, without a grant of arms to himself or to his ancestors, either near or far removed.’

[xii] Fox-Davies, A.C., A Complete Guide to Heraldry, revised by J.P. Brooke-Little, Norroy and Ulster King of Arms, London, Bloomsbury Books, 1985, p. 16, f.2. A practical application of the consequence of arms-bearing in the early twenty-first century is exemplified in the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta, where entry to the Order in the noble grades is based, in part, on proof of the candidate or his family being noble for a determined period of time. The word ‘noble’, as used in the Order of Malta in Ireland, is not restricted to titled nobility but ‘has retained its earlier and broader sense and applies to all who are of noble status by birth or creation.’ With regard to the Irish Association of the Order of Malta, it is held that ‘the outward sign of nobility has been for many centuries the public use of heraldic arms. Those who lawfully use (or bear) such arms are described as armigerous and their right to use a particular coat-of-arms is considered to be a normal attribute of nobility.’ From that viewpoint, ‘the earliest date when a family is known to have had the right to use a particular coat-of-arms has, for the last four centuries or so, come to be regarded as the date of elevation of the family to noble status.’ (‘Notes on noble proofs in general’, The Irish Association of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta, commonly called the Sovereign Order of Malta, revised protocol – May 1984.’)

[xiii] NLI, Dublin, G.O., Ms. 110, Grants, Confirmations and Exemplifications of Arms, Vol. H, 1880-1897, fol. 179.

[xiv] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 85, Draft Grants c.1630-1801, p. 46; Burtchaell, G.D. and Sadleir, T.U. (eds.), Alumni Dublinenses, Alex, Thom & Co. Ltd., Dublin, 1935, p. 161; Vigors, Col. P.D. and French, Rev. J.F.M. (eds.), Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead, Ireland, Vol. III, No. III, 1897, p. 487. An armorial monument at Lynally church dating from the same year of Ulster’s confirmation bears the impaled arms of Coffy and Hide and the inscription ‘This monument was made for Thomas Coffy Clearke and his deare wife Anne Hide and their posteritie Anno Dom: 1684.’ Below the tablet was recorded Rev. Thomas Coffy’s tombstone bearing the inscription ‘Here lyeth the body of Thomas Coffy Clearke, Master in Arts of Trinity Colledge Dublin, Vicar of Fercall and one of His Majestie’s Charles II Justices of the Peace in the King’s County who died March ye 30 1690.’

[xv] NLI, Dublin, G.O., Ms. 111B, Grants and Confirmations of Arms, Vol. L, 1914-1919, fol. 50; Fox-Davies, A.C., Armorial Families, A Directory of Gentlemen of Coat-Armour, 7th Edition, London, Hurst & Blackett Ltd., 1929, p. 1467. The crest in the 1918 confirmation of arms to the descendants of James O Neale was blazoned as ‘out of a ducal coronet a cubit arm the hand holding a sword all Proper and the motto given as ‘Lamb dearg Eirinn.’ The same shield but with a crest of a dexter arm in armour, embowed, holding in the gauntlet a sword all Proper was given as part of the achievement of the descendants of Jorge Owen O Neill ‘The O Neill,’ Peer of the Portuguese realm, Grand Officer of the Royal Household of His Faithful Majesty the King of Portugal, Comte de Tyrone in France, born in 1848 and who died in 1925. In this latter case, above the arms was given the motto ‘Lamh dearg Eirinn aboo’ and below ‘Caelo solo saelo polentes.’

[xvi] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 111F, Grants and Confirmations of Arms, Vol. P, fol. 240.

[xvii] www.nli.ie/en/history of the office of the chief herald.