© Donal G. Burke 2013

It has been held by tradition that those born of the surname Burke or de Burgh derive from William de Burgh, an Anglo-Norman adventurer who arrived in Ireland sometime about 1185. This William died about 1204 and was father of Richard, first Lord of Connacht and grandfather of Walter de Burgh, Earl of Ulster. While written in Latin as de Burgo, letters written as early as 1327 in the Anglo-French language of the day relating to the most prominent members of the family in Ireland give the name as ‘de Bourk,’ suggesting a close link with how the name sounded to the contemporary Irish who wrote the name ‘de Búrc,’ ‘a Búrc’ or simply ‘Búrc’.[i] Based on the phonetics of the Anglo-Norman name in everyday use in medieval Ireland the name de Burgh became Burke or Bourke in that country, with the exception of a small few who in later generations reverted to the former.

The basic elements common to all arms of those armigerous persons of the name Burke or its variants forms, such as Bourke or de Burgh, in Ireland, the descendants of William de Burgh, are the field and ordinary ‘Or a cross Gules’ (a red cross upon a gold shield). A variation upon this included a lion rampant Sable in the upper dexter canton but this lion charge appears to have been a later addition to certain arms and did not form part of the arms of all armigers of the name Burke in the early modern period. It is apparent, however, that the arms ‘Or a cross Gules’ was not borne by the senior-most members of the family immediately following their arrival in Ireland.

The family appear to have been of minor landowning status in England prior to the political rise of both William and his brother Hubert in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries and at that time the arms ‘Or a cross Gules’ was prominently borne by the mainline of another family.

The earliest heraldic arms clearly identifiable as borne by Anglo-Norman magnates that would continue as family arms associated with their descendants date from about the early to mid twelfth century.[ii] It is unlikely, therefore, that any arms later associated with the de Burghs in Ireland predate this period.

Earliest arms

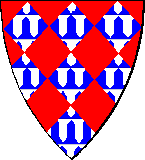

One of the earliest shields associated with a member of this family was that of Hubert de Burgh, who rose to become Justiciar of England and Earl of Kent. This Hubert, whose lands lay, and life was spent, primarily in England, was a brother of William, the first of the family of Ireland.[iii] Hubert bore for arms ‘Lozengy Vair and Gules’ or a variation thereon and illustrations of his shield were given by Matthew Paris in his historical works ‘Chronica Majora’ and ‘Historia Anglorum’, dating from the mid thirteenth century.[iv] The arms of another of this family, one Reymund de Burgh, who drowned in 1230, and believed to have been a nephew or kinsman of Hubert in England, was also given in the same manuscripts as the same as that of Hubert.[v]

Shield of Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent and brother of William de Burgh, progenitor of those of the name Burke in Ireland. (from Boutell’s ‘The Handbook to English Heraldry.’)

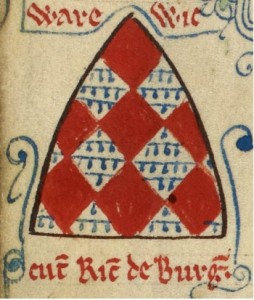

The death of William de Burgh’s son Richard, Lord of Connacht, one time Justiciar of Ireland and nephew of Hubert de Burgh, was recorded by Paris as occurring in 1242 in two of his manuscripts. Richard’s accompanying arms vary in both. In the copy known as British Library Royal Ms. 14 ‘Historia Anglorum’ Richard de Burgh’s arms are shown as identical to those of his uncle and to Reymund de Burgh.[vi] While Paris’ contemporaneous manuscript ‘Chronica Majora’ gives the same arms again for both Hubert and Reymund, the arms of Richard de Burgh are displayed in that manuscript as ‘party per pale Gules and Or, a bordure Vert.’[vii] While Paris gives two differing versions of Richard’s arms, his evidence regarding the de Burgh’s arms may be taken to be generally reliable given that he personally knew Hubert de Burgh and was therefore familiar with details of his family.[viii]

The inverted shield of Richard de Burgh from ‘Historia Anglorum’ dating from circa 1250 to 1259. (c) British Library Board, Royal Ms.14 CVII Historia Anglorum.

The shield of Richard de Burgh, after the ‘Chronica Majora’ of Matthew Paris, dating from the mid thirteenth century.

Or a cross Gules

It was not uncommon for fictitious origins to be ascribed in later centuries to certain arms. In relation to the Burkes, a tradition held that the arms of the mainline of the de Burghs in Ireland was bestowed during the crusades to the Holy Land, when, on the killing of a prominent Saracen by the ancestor of the de Burghs, King Richard I of England dipped his finger in the blood of the fallen and tracing with it a cross in blood upon the gold shield of de Burgh, bestowed on him those arms as ‘Or a cross Gules’ to be held as his family’s thereafter.[ix] That this is of later construction is evidenced by the fact that Richard King of England was engaged on crusade to the Holy Land in the early 1190s, at which time the progenitor of the family in Ireland, William de Burgh, was occupied in Ireland and about which time his children were only born. The de Burghs do not appear to have borne these arms in the late twelfth century and there is likewise no evidence to suggest any of his immediate family in Ireland undertook the crusade to Palestine.

About 1265 Richard de Burgh’s second son Walter, Lord of Connacht, acquired the earldom of Ulster, thus becoming overlord of a large part of the island of Ireland. He died in 1271 and was succeeded by his son Richard, known as the Red Earl of Ulster. In the years between the death circa 1242 or 1243 of Richard Lord of Connacht and the latter years of the thirteenth century, the mainline of the de Burghs in Ireland adopted new arms of a cross upon a simple shield.

Joseph Foster in his ‘Feudal Coats of Arms’ attributes to Walter de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, the arms ‘Or a cross Gules’ on the basis of their appearing as such in Powell’s Roll of Arms and Jenyn’s Ordinary.[x] Powell’s Roll (which Foster renames as ‘Ashmole’), however, simply displays ‘Or a cross Gules’ as the arms of ‘the Earl of Ulster.’ The roll itself, being dated between 1345 and 1351, post dates the period in which the de Burgh’s held the earldom and so could refer to either of the Earls Walter, Richard or the last earl, William. Similarly Jenyn’s Ordinary, collated about the late fourteenth century, post-dates the lives of Walter and his son Richard, Earls of Ulster.

No contemporary medieval compilation or ‘roll’ of arms clearly gives arms for Walter de Burgh as Earl of Ulster. One ‘Walter de Burg’ is given with the arms ‘quarterly Argent and Gules overall a cross of the second (Gules)’ in Walford’s Roll of Arms, dating from circa 1275, but it is unclear if this is a reference to Walter Earl of Ulster. Some commentators have attributed these arms to the Earl but the Roll itself does not specifically state that this is the same Walter.[xi] Another source attributes these arms to one Walter de Burgh holding lands in Norfolk who served as a witness to a deed in 1280, nine years after the Earl’s death.[xii] No evidence is given, however, to justify the attribution of those arms to that Walter either and that same author equates a seal to Walter Earl of Ulster bearing a simple shield with an indented chief.[xiii] However, the original source quoted by that author, Birch’s ‘Catalogue of Seals’ simply stated that that seal was that of one Walter de Burgo, dated during the reign of King Henry III (1207-1272) and made no reference to his being Earl of Ulster.[xiv]

It is clear that at the end of the first two generations of de Burghs in Ireland the arms borne were not those of ‘Or a cross Gules.’ It is uncertain if the cross as heraldic ordinary was adopted by Walter or by his son Richard, but it appears to have been adopted by one or the other at some stage in the latter half of the thirteenth century.

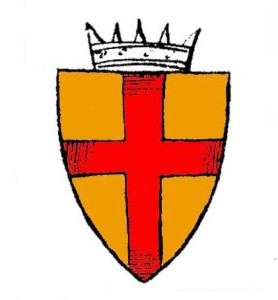

The first of the mainline of the de Burghs clearly identified in contemporary records as bearing a cross as the primary element on his shield appears to be Richard, the Red Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht, who obtained seisin of his estates in 1280. Richard’s seal, dated circa 1305, carried a simple cross upon a plain shield.[xv] The Marshal’s Roll of Arms dated circa 1295 gives his arms as Earl of Ulster as ‘Or a cross Gules’ and the same arms are again replicated for the Earl of Ulster in the Collin’s Roll, dating from the same period, circa 1296.

Arms of de Burgh Earl of Ulster, after the tricked arms of Harl. Ms. 5866, dated circa 1606. The coronet in this case is not a crest but used by the seventeenth century illustrator as an indicator of rank.

Bigod Earls of Norfolk

These arms became inextricably associated with the de Burghs in later years but from a much earlier period had been prominently borne in one form or another by the Bigods, Earls of Norfolk in England. [xvi] The mainline of the Bigod Earls of Norfolk used Or a cross Gules as their arms up to and during the lifetime of Roger 4th Earl of Norfolk. His nephew, Roger, 5th Earl of Norfolk, succeeded to the title in 1270 and served as Marshal of England. He came to use both the Or a cross Gules and also the hereditary arms associated with that office made prestigious by the le Marshall family ‘per pale Or and Vert a lion rampant Gules’.[xvii]

Roger 5th Earl of Norfolk died in 1306 without issue. Four years before his death he surrendered the earldom to the king, who re-granted it to him but entailed only to the heirs of Roger, effectively disinheriting his younger brother John Bigod. On Roger’s death the title became extinct and both title and lands were subsequently granted to a younger brother of the king. Junior branches of the Bigods continued to use variations on ‘Or a cross Gules’ but during the lifetime of the Red Earl of Ulster at the latest, who inherited his Irish estates in 1280 and died in 1326, those arms came to be more associated with the mainline of the de Burghs.[xviii]

It has been suggested that the de Burghs came to use the arms of the Bigods through intermarriage with a descendant of the Bigod family. Richard the Red Earl was grandson of Isabel Bigod, sister of Roger 4th Earl of Norfolk. Isabel married firstly Gilbert de Lacy, son of Walter Earl of Meath and by him had at least three children.[xix] Gilbert died during his father’s lifetime and was survived by two daughters, who became the heiresses of their grandfather Walter de Lacy.[xx] Isabel married secondly Sir John fitzGeoffrey, by whom she had two sons and four daughters. Avelina, daughter of Isabel Bigod and John fitzGeoffrey married Walter de Burgh, Earl of Ulster.

Avelina’s brother Richard fitz John died without a male heir and his sisters Avelina, Joan, Maud and others were his next heirs. Through his mother Avelina, Walter de Burgh’s son Richard, the Red Earl, would inherit part of Richard fitzJohn’s property in Thomond.[xxi]

De Lacy Earl of Ulster

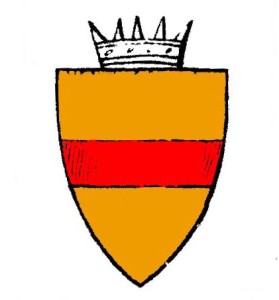

It is noteworthy, however, that the arms which came to be used by the de Burghs, in all likelihood after their acquisition of the earldom of Ulster, resembled to an extent those given in an early seventeenth century armorial as borne by de Lacy, previous earl of Ulster, who were said to have borne both ‘Argent, a fess Gules’ and ‘Or a fess Gules.’ [xxii] Richard the first Lord of Connacht had married Isobel Bigod’s sister in law, Egidia, sister of Gilbert and daughter of Walter de Lacy Earl of Meath. This Walter was brother of Hugh, Earl of Ulster. Walter de Lacy died in 1241 leaving only two granddaughters as heiresses and Hugh de Lacy died in 1243 and, without a male heir or possibly a legitimate female heiress, his Ulster earldom was taken in hand by the King.[xxiii] That earldom was then later granted, in exchange for other lands, to Walter de Burgh.

Arms of de Lacy Earl of Ulster, after the tricked arms of Harl. Ms. 5866, dated circa 1606. The coronet is again used in this case by the seventeenth century illustrator as an indicator of rank and not as a crest.

Immediate family of the Red Earl of Ulster

The Red Earl’s eldest son died without issue in 1304 and his second son Sir John married in 1308 Elizabeth de Clare. John died, however, in 1313 and Elizabeth went on to marry secondly Theobald de Verdun and thirdly Roger D’Amory. Elizabeth’s personal seal, dated circa 1333, carried the arms of her father and three husbands.[xxiv] That of her first husband, John de Burgh, was given as a simple cross upon a plain shield, with a label of three points indicating his position as heir to the earldom of Ulster after the death of his elder brother Walter. Elizabeth, circa 1353, also used another seal displaying arms of ‘per pale, dexter, that of de Clare, (her father) and sinister, that of de Burgh, (a cross without the label); all within a bordure guttée. [xxv] The same Lady Elizabeth de Burgh was patroness of Clare Hall, later Clare College, Cambridge and her arms appear again as those of de Clare impaled with de Burgh within a bordure, apparently guttée, in the seal of that Hall dated from the mid fourteenth century.[xxvi]

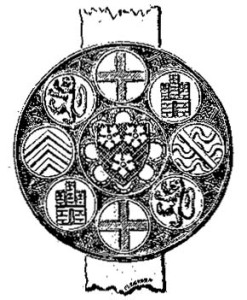

One personal seal of Elizabeth took the shape of a circle, within which were five shields or roundels taking the form of a cross. Two of the roundels were identical, the arms of the de Clare family on either arm of the cross, at the centre that of Roger D’Amory, the lower that of Theobald de Verdun and the uppermost that of de Burgh, a cross on a simple shield, with a label indicating her husband John’s position as heir after the death of his elder brother.[xxvii]

Seal of Elizabeth, Lady Bardolf, daughter of Roger D’Amory, carrying the shield of de Burgh ‘Or a cross Gules’ alongside those of D’Amory and de Clare, with those of her husband John, Lord Bardolf at centre. (from Boutell’s ‘The Handbook to English Heraldry.’)

The Red Earl’s final heir, after the death during his lifetime of both his eldest and second sons, was his grandson William, son of John de Burgh and Elizabeth de Clare, who became the 3rd Earl. The 3rd Earl was killed in 1333, leaving eventually only an heiress Elizabeth, through whom her father’s title and properties in time descended to the Mortimer family. The inheritors quartered their arms with that of de Burgh, with Edmund, last Earl of March and Ulster, KG, quartering the Mortimer arms with the ‘Or a cross Gules’ of de Burgh. [xxviii]

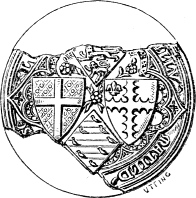

Seal of Matilda of Lancaster, widow of William de Burgh, Earl of Ulster who was murdered in 1333, displaying the shields of her first husband William de Burgh, her second husband Ralph D’Ufford and on a lozenge the arms of her mother’s family de Chaworth. (from Boutell’s ‘The Handbook to English Heraldry.’)

Seal of Edmund Mortimer, dated circa 1400, with quartered arms of Mortimer and de Burgh. (from Boutell’s ‘The Handbook to English Heraldry.’)

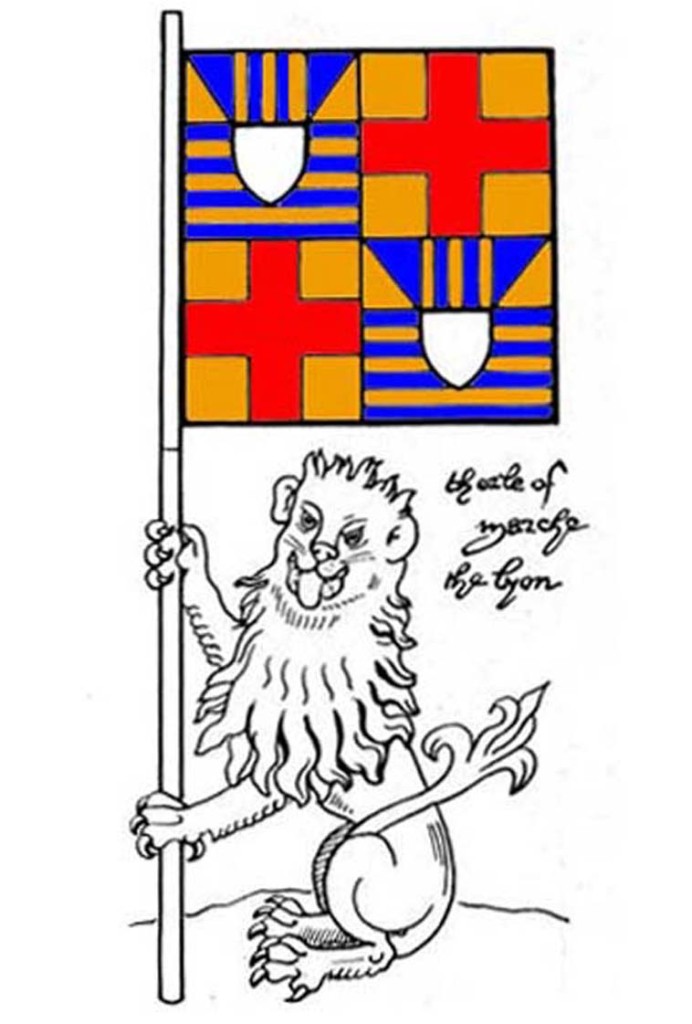

Banner of Roger Mortimer, Earl of March and Ulster, slain in Ireland in 1398, displaying the quartered arms of Mortimer and de Burgh and supported by the white lion associated with the earldom of March. (after a tricked illustration in ’Banners, Standards and Badges from a Tudor Manuscript in the College of Arms,’ 1904.)

As the town of Galway formed part of the estates of the de Burghs and the Mortimers were the heirs in law to those estates, a variation of these arms, quartered but with those of de Burgh in the first and fourth quarters and those of Mortimer in the second and third served as the arms of the town from the late fourteenth century to the late fifteenth century.[xxix]

The black dragon of Ulster

When Edmund Mortimer died in Ireland in 1425, his vast lands, including the former de Burgh earldom of Ulster and lordship of Connacht, descended through his sister Anne to his nephew, the young Richard Duke of York. Born in 1411, this Richard became, at the age of fourteen, heir to two branches of the English Royal family with a strong claim to the throne of England. His father had been executed in 1415 for plotting to install Edmund Mortimer on the throne in place of King Henry V, claiming the then king as the son of a usurper.

‘A blacke dragon’ was given as one of the badges that Richard 3rd Duke of York, son of Richard Duke of Cambridge and Anne Mortimer, was said to utilise ‘by the erldom of Wolstr (Ulster).’[xxx] (A Badge was an emblem used to signify allegiance or ownership and the badge of a particular lord could be found upon his banner, his property or on the apparel of his retainers.) York’s use of the black dragon served as a reference to his descent from the de Burgh Earls of Ulster and his inheritance through his mother, the heiress Anne, of their estates.

Richard Duke of York was appointed Lord Lieutenant (the King’s Representative) of Ireland in 1447 and in 1449 he arrived in Ireland. On his arrival among the Irish chieftains of Ulster to take their submission he was said to have unfurled the ‘black dragon’ banner associated with the earldom of Ulster, a reminder of his own descent from the de Burgh Earls to whom the ancestors of the Irish chieftains had owed allegiance.[xxxi] It is unclear if this dragon emblem dated from the period of the de Lacy earldom but was clearly associated with the de Burgh’s earldom.

York’s attempts to gain ultimate authority in England were thwarted at the battle of Ludlow in 1459 and in 1460 he was killed. The House of York did, however, attain the throne in the person of Richard’s two sons; Edward and Richard and on the accession of Edward as King Edward IV, the former de Burgh earldom of Ulster and Lordship of Connacht were merged in the Crown of England.

The dragon of Ulster, derived from his de Burgh ancestors and described as ‘a black dragon segreant with gold claws’ was among the badges used by King Edward IV.[xxxii] Other badges used by the same king included a falcon with a closed fetterlock, the black bull of the de Clare family, a sun in splendour, a white hart and a white wolf.[xxxiii] The latter, a white wolf, was also given in one manuscript as a badge associated with the Ulster earldom.[xxxiv]

It is worthy of note that, as Sir Peter Gwynn-Jones, Garter King of Arms, explained in his book ‘The Art of Heraldry,’ the heraldic dragon appeared with only two legs prior to the fifteenth century. The two legged dragon came to be known later as a ‘wyvern’ while a dragon was shown with four legs from the fifteenth century. This would suggest that, if the de Burghs as Earls of Ulster carried a black dragon on a banner or as a badge, the heraldic creature would have appeared more akin to the modern wyvern than the modern dragon.

Association with Ulster and the Earldom

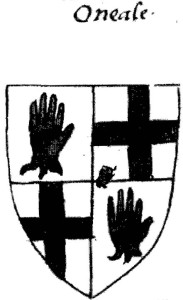

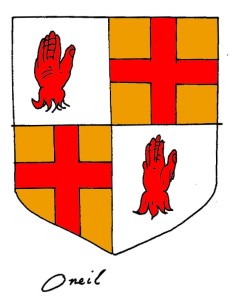

Through Walter de Burgh and his immediate de Burgh descendants as Earls of Ulster ‘Or a cross Gules’ came to form what would be, in the modern period, the basis for the arms of the province of Ulster. By the late sixteenth century or early seventeenth century the de Burgh arms came to be utilised by at least one O Neill as a device associating him with a claim to Ulster itself, with his bearing for arms quarterly first and fourth, Argent a dexter hand couped at the wrist Gules, second and third Or a cross Gules.[xxxv]

Arms of O Neill from Harl. Ms. 6096, dated circa 1603. Those of ‘Camock Oneale Erle of Tirrone’ were given in the same book with a dexter hand appaumee between two lions combatant.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, in which time the administration of King Henry VIII sought to bring the Irish chieftains to subjection, the northern chieftain Con bacach O Neill was desirous to have the title of Earl of Ulster. His ambitions in that regard were opposed by King Henry VIII, who expressed wonder that ‘a man who had so frequently and heinously offended’ should think ‘of asking the name and honour of Ulster, one of the great Earldoms of Christendom, and the King’s proper inheritance.’[xxxvi] King Henry VIII wrote to the Lord Deputy and Council in Ireland from Westminster in April of 1542 refusing the title of Earl of Ulster to O Neill and again in July from Hampton Court informing them that O Neill may be created a peer by any title except that of Earl of Ulster.[xxxvii] He was thereafter created 1st Earl of Tyrone.

Hugh 2nd Earl of Tyrone is given on different occasions in the records of the Ulster King of Arms, between 1595 and 1606, with two different coats of arms. While he is referred to about 1606 as ‘Hugh O Neill, traitor Earl of Tyrone’, his arms are shown as Argent a dexter hand couped at the wrist Gules, on either side, supporting the hand a lion rampant combatant Gules and over all a bend Sable. To signify his rebellion his coronet is shown aslant.[xxxviii] His arms, as Earl of Tyrone and Baron of Dungannon, were given elsewhere in the same office records, between about 1595 and 1603, as quarterly first and fourth, Argent a dexter hand couped at the wrist Gules, second and third Or a cross Gules.[xxxix]

Arms of O Neill Earl of Tyrone and Baron of Dungannon after the tricked arms of Harl. Ms. 5885, dated circa 1603.

It is noteworthy that in associating the armiger with the earldom or territory of Ulster, the heraldic authorities or the armiger at this date utilised the simple Or a cross Gules, without any additional charge in any of the cantons. They thereby incidentally made the distinction between the arms of the earlier Earls of Ulster and the contemporary arms borne about that time by the then head of the Clanricarde Burkes and the Mayo Burkes, descendants of a junior line of the de Burghs.

In 1552 the Office of Arms was established in Ireland with the appointment of the first Ulster King of Arms, the heraldic officer with jurisdiction over Ireland. The Ulster King of Arms derived his authority from the Crown and his arms and that of the Office of Arms, by virtue of prominently bearing in its composition the arms of Ulster, incidentally carried thereby the arms of de Burgh, as did to a lesser degree its eventual successor in the Republic of Ireland, the Genealogical Office, its arms being registered in 1945.[xl] The arms of the Norroy King of Arms, inheritor of the Ulster King of Arms title in Great Britain, likewise incorporated a variation of the Ulster arms thereafter as Norroy and Ulster King of Arms.

While the state of Northern Ireland, created in the early twentieth century, bore for arms an elaboration upon ‘Argent a cross Gules’ the grant of supporters to the arms of the Government of Northern Ireland included a banner bearing the de Burgh arms of Ulster ‘Or a cross Gules’ between the forelegs of its sinister supporter; a rampant stag.[xli]

In the west the long association of the de Burghs or Burkes with the town of Loughrea, once the seat of power of the de Burgh Earls in Connacht and their descendants the Burke chieftains and Earls of Clanricarde, saw that town incorporate the cross Gules into the composition of its town arms in the late twentieth century.

Irrespective of any earlier arms borne by early members of the family in Ireland and whether Walter Earl of Ulster bore any arms other than ‘Or a cross Gules’, over time it came to be believed by their descendants and held by later heraldic authorities, that ‘Or a cross Gules’ dated from William de Burgh, the progenitor of the family, as all the armigerous branches of the name in Ireland, not only those descended from his son Richard, first Lord of Connacht, but also those now believed to be descended from William, Sheriff of Connacht, a younger son of the progenitors, came to bear arms based on the basic red cross on a gold shield.

Continued in Part II

[i] Sayles, G.O. (ed.), Documents on the Affairs of Ireland before the King’s Council, Dublin, I.M.C., 1979, pp. 126-7. No. 155. ‘The advice tendered to Elizabeth de Burgh by her council in Ireland 1327.’

[ii] Bartlett, R., England under the Norman and Angevin kings 1075-1225, The New Oxford History of England, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2000, p.247. The earliest given by Bartlett are those of Waleran, Count of Meulan, who died in 1166 and those of Gilbert de Clare, who died 1152.

[iii] Nicholls, K.W., A Charter of William De Burgo, Analecta Hibernica, No. 27, IMC, Dublin, 1972, pp. 120-122. That William had a brother named Hubert is confirmed in a charter whereby William de Burgh granted lands in Meath and in Connacht to William le Petit, Seneschal of Meath and from 1192-1194 joint Justiciar of Ireland. The lands he granted to le Petit in Meath included lands about the parish of Moymet, which Walter de Lacy had previously given to this William de Burgh and his brother Hubert de Burgh. William de Burgh describes Hubert in this charter as ‘Hubert de Burgo fratri meo’. William de Burgh’s eldest son Richard is clearly described as Hubert de Burgh’s nephew in 1234; Sweetman, H.S. (ed.), Calendar of Documents relating to Ireland, 1171-1251, London, Longman & Co., Trubner & Co., 1875, p. 329. No. 2217, dated Oct. 7, 1234. ‘The King notifies that Richard de Burgh has made a fine with him of 3,000 marks to have such seisin of his lands of Connaught as he had when the King disseised him owing to his account at the time when he was justiciary of Ireland, and the strife with Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent, his uncle,’ etc. (Pat. 18 Henry II, m.3)

[iv] British Library, Royal Ms. 14. C. VII, Historia Anglorum, dated 1250-1259, fol. 135v.

[v] British Library, Royal Ms. 14. C. VII, Historia Anglorum, dated 1250-1259, fol. 116v. Reymund is therein referred to as ‘Reimund de Burgo nepos Huberti.’ His arms in the Historia Anglorum are simply drawn in outline form, without colour.

[vi] British Library, Royal Ms. 14. C. VII, Historia Anglorum, dated 1250-1259, fol. 134v. ‘Scutum Ricardi de Burgo.’

[vii] Lewis. S., The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora, California Studies in the History of Art, (Horn, W. and Marrow J. (ed.), University of California Press in collaboration with Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1987, Appendix 2, pp. 450-454. Chronica Majora, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Ms. 16, f. 160v; Richard de Burgo, f. 162; Hubert de Burgh, fol. 76v. (80v.); Reymund de Burgh.

[viii] Lewis. S., The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora, California Studies in the History of Art, (Horn, W. and Marrow J. (ed.), University of California Press in collaboration with Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1987, p. 5; For his familiarity with heraldry refer to ‘Vaughan, R., Matthew Paris, Cambridge, University Press, 1958, pp. 250-253.

[ix] Bourke, E., Burke People and Places, Whitegate and Castlebar, Ballinakilla Press and De Burca Rare Books, 1984, p. 8.

[x] Foster, J., Feudal coats of arms, James Parker & Co., London, 1902, p. 41.

[xi] Nichols, J.G. (ed.), The Herald and Genealogist, Vol. IV, London, J.G. Nichols and R.C. Nichols, 1867, pp. 337-340. This same source attributes arms to William, brother of Walter Earl of Ulster of ‘quarterly Or and Azure’ on the basis that one of that name was attributed those arms in the Charles Roll of Arms, which date from about 1285, but again there is no evidence to confirm that the armiger listed in that Roll was brother to the Earl of Ulster.

[xii] Moor, C. (coll.), Knights of Edward I, Vol. I, ‘A to E’, The Publications of The Harleian Society, Vol. LXXX, Leeds, John Whithead and Son, Ltd., 1929, p. 162.

[xiii] Moor, C. (coll.), Knights of Edward I, Vol. I, ‘A to E’, The Publications of The Harleian Society, Vol. LXXX, Leeds, John Whithead and Son, Ltd., 1929, p. 162.

[xiv] De Gray Birch, W., Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol. II, Trustees of the British Museum and Longman and Co, etc., 1892, p. 582. No. 7949. ‘Walter de Burgo,’ ‘a shield of arms of early shape, a chief indented’ bearing the inscription ‘+ S’ Walteri de Bvrgo.’

[xv] Richardson, D., Magna Carta Ancestry: a Study in Colonial and Medieval families, 2nd edition, Salt Lake City, D. Richardson, 2011, p. 357. Refers to ‘Ellis, R.H., Catalogue of Seals in the Public Records Office, Vol. I, 1978;13.

[xvi] British Library, Cotton Ms. Nero D. I., f.171v. Matthew Paris, ‘Book of Additions,’ dated circa 1250. The arms Or a cross Gules were depicted by Paris as borne by the ‘Comitis Bigod’.

[xvii] Foster, J., Feudal coats of arms, James Parker & Co., London, 1902, p. 25. Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and Earl Marshal of England bore ‘per pale Or and Vert a lion rampant Gules’ at the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Rauf Bigod bore the same arms oppressed by a baston Argent.

[xviii] De Gray Birch, W., Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol. II, Trustees of the British Museum and Longman and Co, etc., 1892, pp. 508-9. Ralph Bigot, Lord of Stokton, etc., Counties Norfolk and Suffolk, knt., circa 1368 used a seal carrying ‘a shield of arms; one a cross engrailed five escallops.’

[xix] This Gilbert was brother of Egidia de Lacy, wife of Richard de Burgh, first Lord of Connacht.

[xx] Curtis, E., A History of Medieval Ireland, London, Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1978, pp. 137-8.

[xxi] Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, Vol. III, Edward I, London, H.M. Stationary Office, 1912, p. 391. No. 507. Richard fitzJohn, 27 Edward I.

[xxii] British Museum, Harl. Ms. 5866 (N.L.I. Dublin POS no. 1426)

[xxiii] Knox, H.T., Notes on the Marriages and Successions of the de Burgo Lords of Connaught and the Acquisition of the Earldom of Ulster, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1898, p. 415; Curtis, E., A History of Medieval Ireland, London, Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1978, pp. 137-8.

[xxiv] De Gray Birch, W., Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol. II, Trustees of the British Museum and Longman and Co, etc., 1892, p. 580. Nos. 7934-9.

[xxv] De Gray Birch, W., Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol. II, Trustees of the British Museum and Longman and Co, etc., 1892, p. 580. No. 7940.

[xxvi] De Gray Birch, W., Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol. II, Trustees of the British Museum and Longman and Co, etc., 1892, p. 33. No. 4734.

[xxvii] Montagu, J. A., A guide to the study of heraldry, William Pickering, London, 1840, p.37.

[xxviii] Foster, J., Feudal coats of arms, James Parker & Co., London, 1902, p. 41.

[xxix] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, pp. 243-5. ‘A Description of the Corporate Arms used by the Town of Galway at Different Periods.’

[xxx] Planché, J.R., On the badges of the House of York, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Vol. XX, London, printed for the Assoc., 1864, pp. 18-33. ‘In the year 1813 Sir Henry Ellis, then Principal Librarian at the British Museum, communicated to the Society of Antiquaries An Enumeration and Explanation of the Devices borne as Badges of Cognizance by the House of York, being the copy of a memorandum written on a blank leaf of parchment at the beginning of the Digby MS. No. 22; the handwriting, in Sir Henry’s opinion, being contemporary with Richard Duke of York, father of King Edward IV.’

[xxxi] Curtis, E., Richard, Duke of York, as Viceroy of Ireland, 1447-1460; With Unpublished Materials for his Relations with Native Chiefs, J.R.S.A.I., Seventh series, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1932, p. 165.

[xxxii] Rothery, G.C., Concise Encyclopedia of Heraldry, Senate, London, 1994, p.66. (First published as ABC of Heraldry, Stanley Paul & Co., 1915)

[xxxiii] Rothery, G.C., Concise Encyclopedia of Heraldry, Senate, London, 1994, p.226. (First published as ABC of Heraldry, Stanley Paul & Co., 1915)

[xxxiv] Planché, J.R., On the badges of the House of York, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Vol. XX, London, printed for the Assoc., 1864, p. 27. Reference is made to the white wolf as a badge attributed in a Lansdowne MS. to the earldom of Ulster.

[xxxv] British Museum, Harl. Ms. 5885 (N.L.I. Dublin POS no. 1426) and British Museum, Harl. Ms. 6096 (N.L.I. Dublin POS no. 1427)

[xxxvi] Sidney, H., Sir Henry Sidney’s Memoir of his government of Ireland 1583, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, First series, Vol. III, 1855, p. 46. Footnote no. 6.

[xxxvii] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, pp. 62-3.

[xxxviii] British Museum, Harl. Ms. 5866 (N.L.I. Dublin POS no. 1426)

[xxxix] British Museum, Harl. Ms. 5885 (N.L.I. Dublin POS no. 1426) Harl. Ms. 6096, about 1603, gives the arms of ‘O Neale’ as ‘quarterly first and fourth, Argent a dexter hand couped at the wrist Gules, second and third Or a cross Gules’, it give those of ‘Camock O Neale, Earl of Tirone’ as Argent a dexter hand couped at the wrist Gules and on either side, supporting the same, a lion rampant combatant Gules.

[xl] Hood, S., Royal Roots, Republican Heritage, The Survival of the Office of Arms, Dublin, The Woodfield Press in association with the National Library of Ireland, 2002, plate 1.

[xli] Hood, S., Royal Roots, Republican Heritage, The Survival of the Office of Arms, Dublin, The Woodfield Press in association with the National Library of Ireland, 2002, p. 126.