© Donal G. Burke 2013

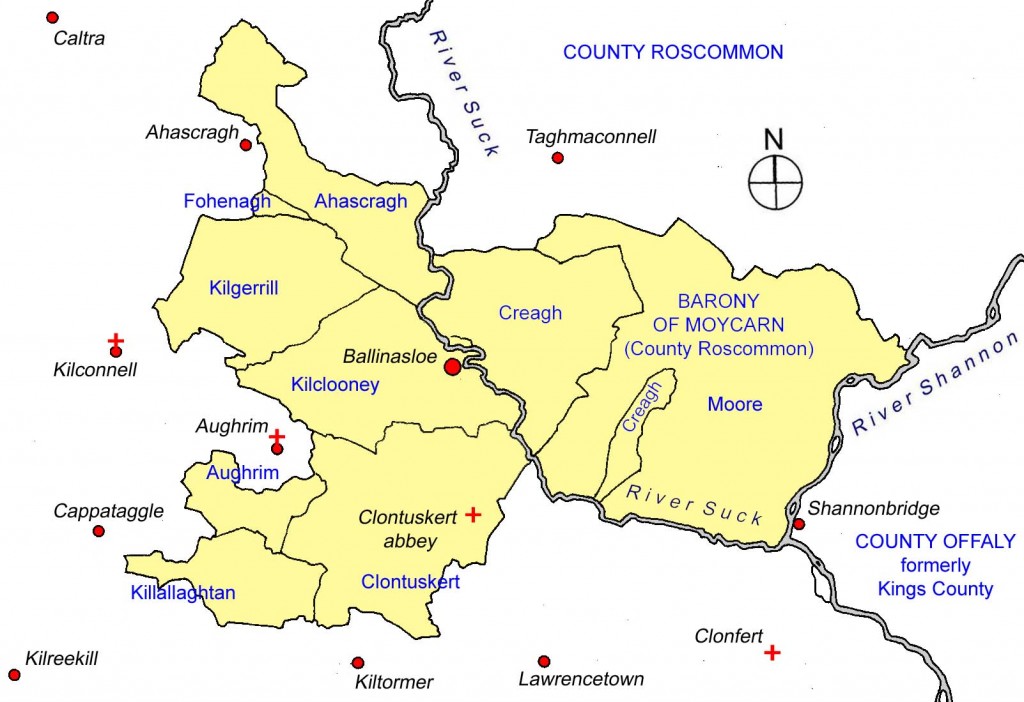

In the late medieval period a large territory within Uí Maine, the ancestral lands of the O Kellys in the eastern region of the later County of Galway, was occupied by a junior sept of the name, the head of which was a tributary of the more senior O Kelly chieftain of Uí Maine. Known as the Clann mhaicne Eoghain, ‘the family of the sons of Eoghan’, the family derived their name from Eoghan finn O Kelly, a younger son of Domhnall mór O Kelly, chieftain of Uí Maine in the mid thirteenth century. Their territory within Uí Maine straddled the River Suck and on the western side of the river included the parishes of Kilcloony, Kilgerrill, Killallaghtan and part of the parish of Clontuskert. On the eastern side of the Suck their lands lay in the parishes of Creagh and Moore.[i] In the seventeenth century their ancestral lands came to form part of the half-barony of Clonmacnowen in County Galway and the half-barony of Moycarn in County Roscommon.

The half baronies of Clonmacnowen, County Galway and Moycarn, County Roscommon (in yellow), on either side of the River Suck, as they stood in the mid nineteenth century, wherein lay the lands associated with the Clann mhaicne Eoghain sept of the O Kellys, with various ecclesiastical centres, modern towns and villages (in red).

Origin of the family

The O Kellys of east Galway are an offshoot of the wider Uí Maine family group, whose ancestor has traditionally been held to be one Maine mór, son of Eochaidh feardaghiall, chief of a tribe of people who established themselves as the dominant group in the south-eastern region of Connacht by about the end of the fifth century.[ii]

The ancient Irish tract ‘life of St. Grellan’ describes this family grouping as ‘the race of Colla da Chríoch,’ from whom they were said to be descended and relates the story of their migration from Oirghialla in Ulster, by way of an area known as Druim clasach and Tír Maine (later Anglicised ‘Tir Many’) in what would later be known as County Roscommon. In this account their leader Maine, son of Eochaidh, is said to be of Goedilic descent, a race of people who came to dominate the earlier tribes of Connacht. The historian Rev. Patrick K. Egan, however, in his book ‘the Parish of Ballinasloe’ was of the opinion that it is more likely that Maine mór and his tribe originated in County Roscommon rather than Ulster and were of an earlier race settled in Ireland before the Goedelic.

Maine mór and his descendants appear to have subjugated many of the existing tribes and peoples that inhabited their land and established a petty kingdom, covering much of the later east Galway named from their progenitor as Uí Maine (later Anglicised as ‘Hy Many’). The senior-most family descended from this Maine was the O Kellys, from whom the rulers or chieftains of Uí Maine were drawn.

Original extent of the territory of Uí Maine

The nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan described the original extent of the territory of Uí Maine or Hy Many as extending ‘from Clontuskert, near Lanesborough in the county of Roscommon southwards to the boundary of Thomond or the county of Clare and from Athlone westwards to Seefin and Athenry in the present county of Galway.’ It included the later parish of Lusmagh, a narrow strip of land that extended eastward across the River Shannon towards Leinster and extended from there, on the Connacht bank of the Shannon down to Lough Derg and to the lake or river of Graney in the north eastern corner of the modern County Clare.

In addition to its application as a territorial name, the term Uí Maine was also applied to the extended family grouping that encompassed all the descendants of Maine mór and many of the later principal native Irish families who ruled or populated the territory such as the O Maddens, O Lorcans and MacCuolahans shared a common descent with the O Kellys of Uí Maine.

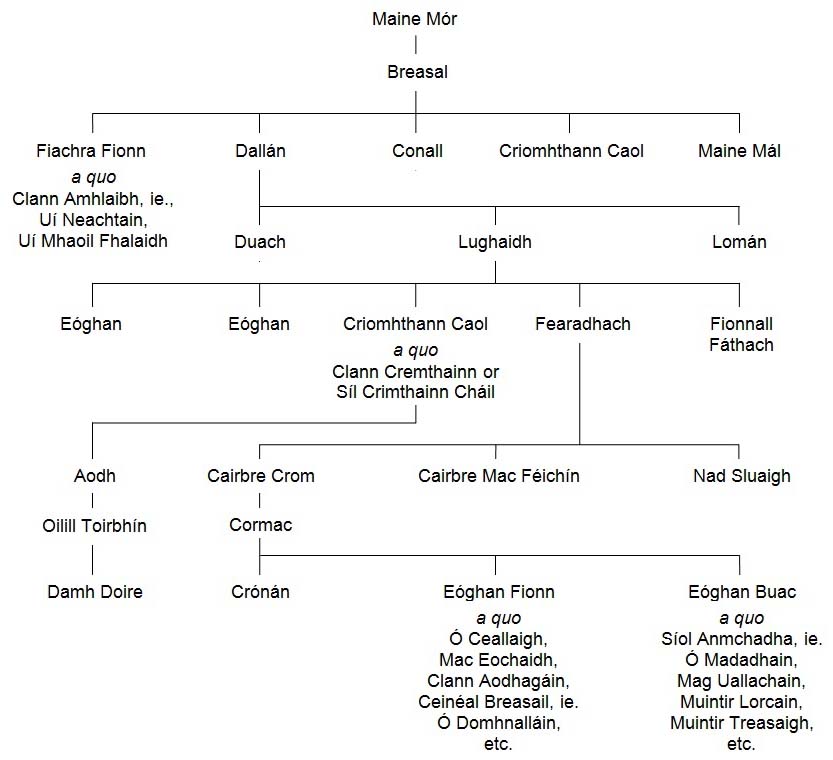

Most of these senior descendant families of the Uí Maine claim descent more specifically from Cairbre crom, a fifth generation senior descendant of Maine mór, reputed to have flourished about the early or mid sixth century A.D. This Cairbre crom reputedly had one son, Cormac, who in turn is said to have had three sons; Crónan, Eoghan fionn ‘the fair’ and Eoghan buac. While families such as the O Maddens and Cuolahans derived their descent from Eoghan buac’s son Anmchadh and were identified as the ‘Siol Anmchadha’, the ‘seed’ or ‘posterity’ of Anmchadh, the O Kellys descended from Eoghan finn.

Pedigree showing various prominent early members of the Uí Maine, derived from MacFirbisigh’s seventeenth century ‘Great Book of Irish Genealogies.’

Ceallach

The O Kellys derive their name from Ceallach, said to have been fourteenth in descent from Maine mór. O Donovan was of the view that this Ceallach may have flourished in the mid ninth century and died about 874, basing his calculation on the fact that one Cathal MacOilioll (‘son of Ailill or Oilill’) chieftain of Uí Maine died in 844 and this Cathal was given as being a generation earlier in descent from Maine mór in pedigrees. It is unclear if Ceallach ever held the chieftaincy of the territory as Cathal son of Oilill was mentioned as chieftain in 834 at which time he plundered the religious foundation at Clonmacnoise and defeated the Irish king of Munster, while, as O Donovan observed, no mention was made of Ceallach in Irish Annals.[iii]

There is much confusion relating to the pedigrees at this time and another reference to the same Ceallach, in which he granted a number of townlands to the Church at Clonmacnoise as ‘Kellagh mac Finachta mic Oillilla mic Innraghta mic Fithiollaigh mic Dluthaigh mic Dithcolla mic Eoghain finn mic Cairbre croim.’[iv]

A number of the chieftains of Uí Maine at this time about the end of the ninth and beginning of the tenth century were of a different line of the Uí Maine than Ceallach or Ceallach’s son Aedh (later anglicised ‘Hugh’).[v]

Ascendancy of the line of Ceallach

Ceallach’s grandson Murchadh, son of Aedh son of Ceallach is believed to have succeeded to the chieftaincy of Uí Maine after the death in 936 of the chieftain Murchadhan son of Sodhlachan, of a different line of the Uí Maine, descended from Criomhthann Caol. At his death in the year 960 he is referred to as ‘Murchadh son of Aedh, lord of Hy Many in Connacht.’[vi]

Thereafter the descendants of Ceallach appear to have maintained for much of the time the ascendancy among the other family branches in the kin group. Murchadh appears to have been succeeded by his brother Geibhennach son of Aedh and was killed in battle at Ceis Corainn.[vii] Another of the family, Tadhg mór (‘the great’), son of Murchadh, attained the chieftaincy about the year 1001 and was killed at the battle of Clontarf in 1014, fought between the High King of Ireland and the Irish King of Leinster and his Norse allies. Fighting on the side of the High King Brian Ború, he was slain, according to a later poem, ‘ina onchoin a ndiaidh Danmarc,’ translated by O Donovan as ‘as a wolf-dog pursuing the Dane.’[viii]

Connor son of Tadhg mór appears to have been king of Uí Maine after his father, but it is unclear if he immediately succeeded him. His death in battle in Meath in the year 1030 as ‘lord of Uí Maine’ was recorded in the Gaelic ‘Annals of the Four Masters’, but prior to that the same annalists record the death in 1019 of Donal son of Muireadhach, chief of Uí Maine. Donal’s descent is uncertain but the line of Tadhg mór appears to have regained the chieftaincy after him.

A conflicting account, given in a fourteenth century poem praising a later O Madden, gives that O Madden’s ancestor, Gadhra mór son of Dunadhach, as holding the office of chieftain of all Uí Maine following the death at Clontarf of Tadhg mór. This was discounted by O Donovan, who asserted that it in all likelihood a construction of the poet’s imagination to inflate the history of the O Madden chieftain and did not agree with the obituary of this Gadhra mór, who was described by the annalists at his death in 1027 as ‘lord of Síl Anmchadha’, the area of Uí Maine under the chieftaincy of O Madden.[ix] Síl Anmchadha would go on to become an autonomous territory under the O Maddens, separate from the territory of the O Kellys.

As a Gaelic territory, the kingship or chieftaincy of Uí Maine was open to all eligible men within the extended ruling house of the former chieftain. The kingship therefore did not descend from eldest son to eldest son by primogeniture. Donnchadh, one of the immediate family, held the chieftaincy for a time until in 1074 he was killed by his kinsmen or relative Tadhg son of Connor son of Connor son of Tadhg mór. O Donovan, in contradiction of a number of pedigrees, gives this Tadhg as the father of Diarmuid who in turn was father of Connor Moenmoy O Kelly, king of Uí Maine.

Connor ‘Moenmoy’ was king of Uí Maine in the mid to late twelfth century and together with his son Tadhg ‘tailteann,’ his brother Diarmuid and Melaghlin the son of Diarmuid O Kelly and their followers, was killed in battle in 1180 by Connor Moenmoy O Connor, the son of Rory O Connor, King of Connacht. The slain O Kelly king, according to tradition, was reputed to have built the chapel known as O Kelly’s Church at Clonmacnoise in 1167 and, in the territory of Moenmoy (a wide area about Loughrea) erected twelve churches and presented three hundred and sixty-five chalices to the Church.[x]

The arrival of the Anglo-Normans

In the late twelfth century a group of Anglo-Norman adventurers landed in Ireland and within a short period the Anglo-Norman lordship of Ireland was established by the King of England. The king of Uí Maine at the arrival of the first organised wave of Anglo-Normans into Ireland appears to have been Murchadh son of Tadhg O Kelly, but he was killed in 1186 by Connor Moenmoy O Connor. It is unclear if he was succeeded immediately thereafter by Domhnall mór O Kelly, son of Tadhg tailteann, as some pedigrees state Domhnall mór only attained the chieftaincy about 1203.

Grants to various Anglo-Normans within Uí Maine or Omany

From the first years of the thirteenth century the King of England had taken to himself lands about Athlone, on the borders of the wider O Kelly territory of Uí Maine. The area was strategically important as a crossing point on the Shannon and a base from which to keep a check on the O Connor Kings of Connacht and his own knights.

In 1204 King John of England came to an arrangement with Cathal crobhdearg (ie. ‘red hand’) O Connor, the Gaelic king of Connacht, in which the English king was to have two cantreds out of the O Connor kingdom of Connacht for his own use. The cantreds taken by King John in this agreement were Tirmany and part of Uí Maine, the ancestral lands of the O Kellys, to be known as the cantred of Omany.[xi] Land about Athlone and Roscommon were acquired by a small number of colonists initially and, in 1210, the King had a royal castle built at Athlone and further lands within Tirmany and Omany were parcelled out among the same colonists.

The King of England extended a grant of Connacht to the Anglo-Norman William de Burgh and in 1235 his son Richard de Burgh succeeded in gaining effective control over the O Connor kingdom. About 1252, less than twenty years after the conquest, one Oliver de Aspreville had a grant of lands in Omany about Aughrim from the Crown.[xii] By the following year these lands were acquired by Sir Richard de Rupella.[xiii]

In 1253 the Crown granted the two Manors of Aughrim and Suicin in Omany to Sir Richard de Rupella (also known as de Rokele or Rochelle).[xiv] The Manor of Suicin is believed to have been situated about the east bank of the River Suck about Ballinasloe in the heart of lands that would come to be regarded as those of a sept of the O Kellys known as the Clann mhaicne Eoghain.[xv]

De Rupella went on to acquire a sizeable estate in the area, in 1258 receiving a grant from Prince Edward, the King’s eldest son, of the entire cantred of Omany.[xvi] De Rupella encountered strong opposition within Omany from the O Kellys and the native Irish and found it difficult to derive a substantial rental income from the lands. It is unclear if he or his son introduced a small number of colonists on their lands but for the most part his lands appear to have been tenanted by the native Irish, underdeveloped and unproductive.

Between the years 1281 and 1285, the Anglo-Norman Theobald Butler acquired the cantred of Omany and other lands from Philip de Rupella, including the Manor of Suicin.[xvii] The Butlers, like de Rupella, was vigorously opposed on occasion by the O Kellys, with the Butler lands about Aughrim burned in 1307.

Decline of the Anglo-Norman colony

By the early fourteenth century the Anglo-Norman colony throughout Ireland was in decline and in 1333 William de Burgh, Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht was murdered. With the sudden loss of the Earl without a male heir and infighting among the leading members of the family, the principal lordship in Ireland began to crumble. The English Crown was not in a position to adequately address the situation and in the turmoil that followed in Connacht, the native Irish such as the O Kellys, began to expand and regain ground previously lost to the Anglo-Normans.

The Manor of Suicin and all of the Butler lands were thereupon taken by the O Kellys and, with the effective power of the English Crown reduced to an area about Dublin by the mid fifteenth century, remained in the possession of their descendants into the sixteenth century.

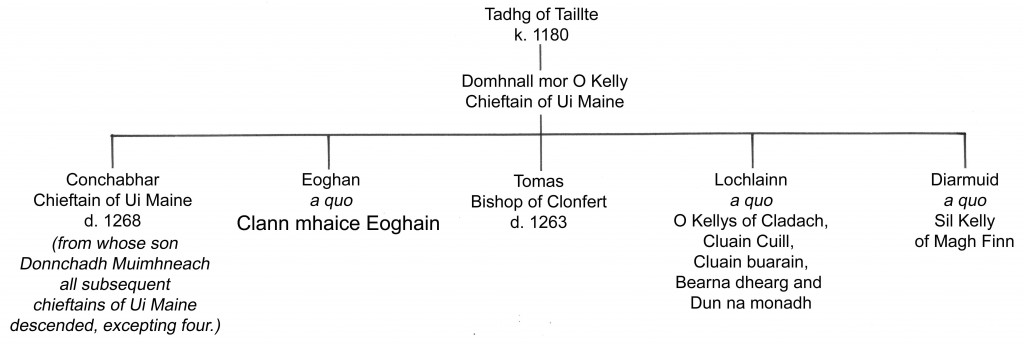

The descendants of Domhnall mór, chieftain of Uí Maine

Domhnall mór O Kelly, chieftain of Uí Maine in the early thirteenth century, was said to have married Duvcola, a daughter of Domhnall mór O Brien, King of Munster and to have had five sons; Conchabhar, Eoghan (also given as Eoghan finn, ie. ‘the fair-haired’), Tomas, Lochlann and Diarmuid.[xviii] Conchabhar attained the chieftaincy of Uí Maine and died in 1268. Almost all of the later senior lines of the O Kellys and subsequent chieftains of Uí Maine are held to be descended from Donnchadh Muimhneach, son of Conchabhar, with the exception of four, who were descended from Conchabhar’s younger brother Eoghan finn.[xix]

Domhnall mór’s son Tomás O Kelly pursued a career in the Church and attained the office of Bishop of Clonfert, dying in 1263.[xx]

From the Bishop’s younger brother Diarmuid O Kelly is said to be descended the family of Mac Eochadha, now known as Keogh, ‘who possessed the territory of Magh Finn, containing forty quarters of land and comprising the entire of the parish of Taughmaconnell’ across the River Suck in the later County Roscommon.[xxi]

The sept of Clann mhaicne Eoghain

From Domhnall mór’s second son Eoghan (or third according to some sources) descended the sept of Clann mhaicne Eoghain, who gave their name to the barony of Clonmacnowen in east Galway, ‘a sept who had always a chief of their own, but who was tributary to the chief of all Hy Many.’[xxii]

Clann mhaicne Eoghain was applied as a term to encompass all those branches of the name descended from Eoghan finn son of Domhnall mór, many of whom formed minor septs or ‘sub-septs’ and branches of their own within the wider Clann mhaicne Eoghain sept. An early account of the wider Clann mhaicne Eoghain gave as their principal strongholds as Áth Nadsluaigh and Tuam Srutha. Both were located in the parish of Creagh on the Suck, protecting the crossing fords on the river. The former is likely to have related to the approximate position of the later castle known as Ballinasloe Castle, while the latter was located further north on the Suck, in the modern townland of Ashford, where the ruins of a castle (known as ‘Toamshroer’ or variants thereon) stood in the early modern period.[xxiii]

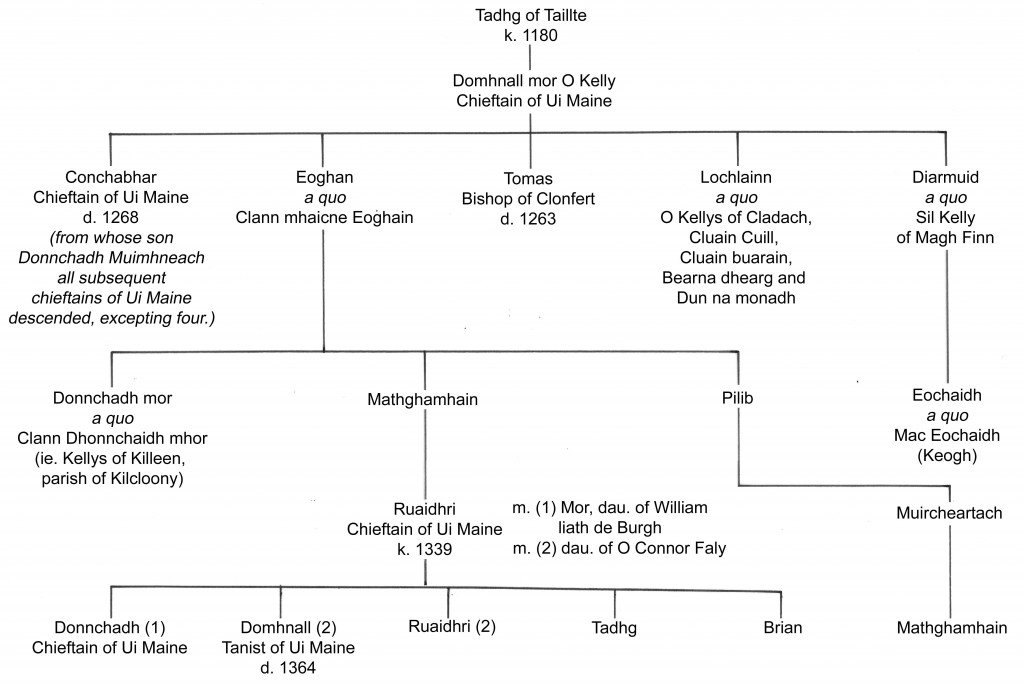

Various genealogies give the sons of Eoghan finn as Donnchadh mór, Mathghamhain (or ‘Mahon’) and Pilib (or ‘Philip’).[xxiv] From Donnchadh mór descended the line of the Kellys of Killeen in the parish of Kilcloony.[xxv] This line has been equated by the historian Fr. Patrick K. Egan with the ‘Clann Donnchaidh mhór’ and although given in some pedigrees as more senior in line of genealogical descent from the progeny of Donnchadh mór’s younger brothers, they would later be found owing services and rents to the descendants of Mathghamhain in the sixteenth century.[xxvi]

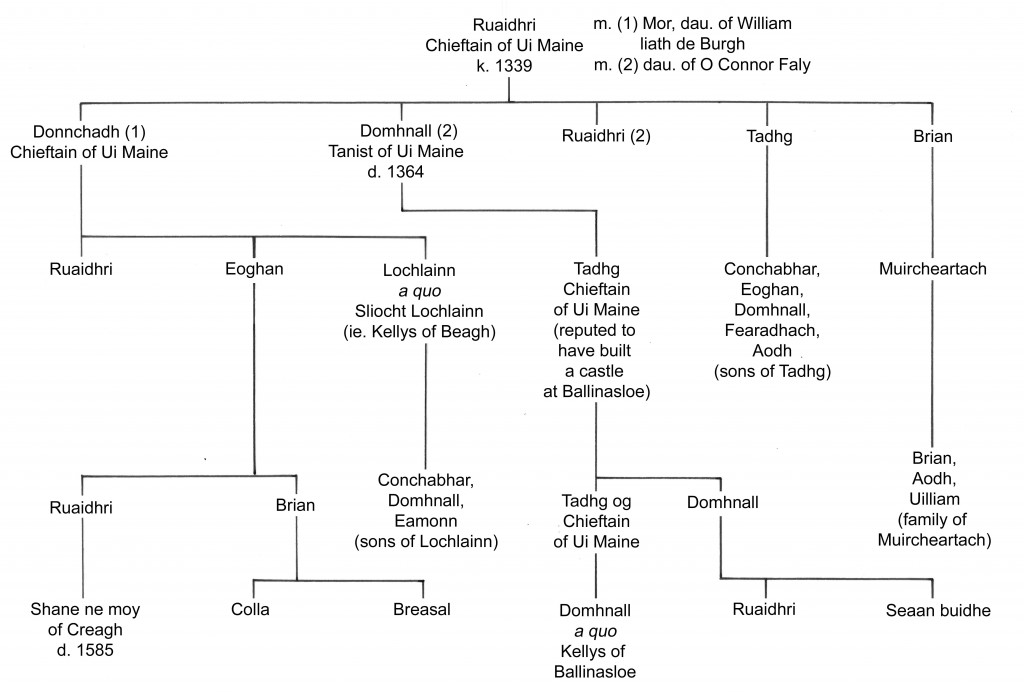

The most powerful descendants of Eoghan finn within the Clann mhaicne Eoghain were the progeny of Mathghamhain. From him derived four chieftains of the wider Uí Maine, the first of whom was his son Ruaidhri (also known as Ruaidhri na maor), described by the Irish annalists as chieftain or lord of Uí Maine in his obituary. He was killed by Cathal son of Aedh O Connor after departing O Connor’s residence to return to his own in 1339.[xxvii] O Donovan described him as chieftain for three years and twice married, firstly to Mor, daughter of William liath de Burgh and secondly to a daughter of O Connor Fahy. [xxviii] By his first wife he is said to have had a son Donnchadh and by his second wife at least two sons; Domhnall and Ruaidhri.[xxix] MacFirbhisigh also attributed to him at least two other sons; Tadhg and Brian.[xxx]

Donnchadh son of Ruaidhri na maor attained the chieftaincy of Uí Maine in the mid fourteenth century.[xxxi] His half-brother, Domhnall son of Ruaidhri held the office of tanist or ‘chieftain designate’ but died while still tanist in 1364.[xxxii] Domhnall’s son Tadhg, however, went on to attain the chieftaincy of Uí Maine and was credited with the construction of a castle of Ballinasloe. He was said to have held the chieftaincy for four years. His son Tadhg óg was the last of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain to hold the chieftaincy and did so for only three days, before he died.[xxxiii] Having three sons, he was ancestor of a branch of the sept known as the Kellys of Ballinasloe whose lands lay in the vicinity of the later castle of Ballinasloe.

Although the line of the Kellys of Ballinasloe, derived from that Domhnall son of Ruaidhri who died in 1364, produced two chieftains, the lines derived from the tanist’s elder half-brother Donnchadh was the more senior in line of genealogical line of descent.

Fr. Egan noted that in the pedigree of this family given by the antiquary John O Donovan, the latter relied to a large degree on a genealogy provided by O Farrell in his ‘Linea Antiqua.’ Fr. Egan was of the view that O Farrell’s pedigree may have been missing a number of generations after Ruaidhri na maor. Nevertheless he believed that the lines of descent of the pedigree were probably correct, if not the detail.[xxxiv]

O Donovan and O Farrell’s pedigree give the sons of Donnchadh son of Ruaidhri na maor as Ruaidhri, Eoghan and Lochlainn.[xxxv] The seventeenth century antiquary Dubhaltach MacFirbhisigh in his ‘Great Book of Genealogies’ gives at least two sons of Donnchadh; Seaan and Lochlainn.[xxxvi] From the latter he gives three sons Conchabhar, Domhnall and Éamonn.[xxxvii] O Donovan described the family derived from this Lochlainn as the Kellys of Beagh, a denomination in the parish of Creagh, near Ballinasloe, on the eastern side of the River Suck. Fr. Egan identified these Kellys of Beagh as the ‘Sliocht Lochlainn,’ ‘the posterity of Lochlainn’ who in the late sixteenth century owed services and rents to the head of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain.[xxxviii]

O Farrell’s pedigree gives the descent of the last head of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain as derived from Eoghan, son of Donnchadh son of Ruaidhri na maor.[xxxix] Eoghan is reputed to have married a daughter of O Madden (which in all likelihood is intended to mean the then chieftain of territory to the immediate south of Clonmacnowen) and had at least one son Ruaidhri, who in turn had a son Shane na maighe (ie. Shane ‘of the plain’), also described as Shane ne moye or John na moy O Kelly, who flourished between the mid to late sixteenth century.

The reassertion of the Crown’s authority in Connacht

From the mid sixteenth century the officials of the Tudor Crown of England had made significant developments in extending the power of the monarch across the country. In tandem with military action against the rebels, the English officials pursued their policy of bringing Ireland in line with English law and land tenure. Part of the Anglicization process involved the dividing of Connacht into shires or counties about the 1570s and into smaller administrative units called baronies. Part of the territory of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain on the western side of the Suck was initially included with the larger territory of the O Maddens (known as Síl Anmchadha) to their south to form the barony of Longford and only later separated from the barony of Longford to form the half-barony of Clonmacnowen in its own right.

Extensive surveys were required to determine the extent and nature of Gaelic landholdings and divisions and about 1574 a list of the chief men of the barony of Longford, ‘which containeth the country of Sillanchy and Clonvicknoyne.’ The principal were recorded as the O Madden, Owen O Madden, Cogh O Madden and Shane ne Moye O Kelly, indicating the prominence of Shane ne Moye who held at that time the headship of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain. A more detailed list of the gentlemen of the barony and their castles or residences identified those of the Clonmacnowen part of the barony as Melaghlin O Kelly of Lykloystrane, Gyllernew O Donnelan of Lysnasille, Shane ne moye of Cloynigne (ie. the modern townland of Cloonigny, in the parish of Kilgerrill), Mahe mcTully of Garowally (Garbally) and Tvell O Donnellen and Gillpatrick O Donnellan of Ballydonnellan.

Shane ne moy O Kelly of Creagh

As the head of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain, Shane ne Moye held extensive lands within the territory of the wider sept. A number of chieftains and lesser heads of septs were induced by the English administration to surrender their lands, which in many cases included those lands that were associated with the office of head of the territory and were his under Gaelic law only for the duration of his term in office. In return for surrendering their lands to the Crown, he would receive a re-grant of those lands at the hands of the Crown under English law, ensuring that these lands were now his personal property as opposed to sept lands, to be passed on within his immediate family under English law. The Irish landholder would hold his lands under English tenure, paying a rent to the Crown and would be theoretically placed in a more secure position with regard to his overlord as he would no longer be subject to the exactions and services due to that overlord. However, he was also required to surrender any services and dues that by tradition he exacted from those within his own immediate territory. Some were allowed to continue those rents and services for a time, to be discontinued after the lifetime of the landholder.

Shane ne Moye surrendered the lands in his control about 1578 and in that year received a grant from the Queen of the lands, rents and services that he claimed as his within Clonmacnowen.[xl] He was described in that grant as ‘Shane ne moy O Kelly, late of Creagh, Co. Roscommon, gentleman’ and the grant comprised ‘all the manors and lands of Towyn alias Twunsrwra, Creagh, Killynmalron, Behagh, Downe(lowe), Garwalle, Clonekyn, Balledonyllan, Tolrose, Keill Garraf, Cowllery, Colleghcally, Cornesharrogh, Lurce, Cillalachdan, Parklosnisker, Ballylough and Belligh, Counties Roscommon and Galway, also all rents and services of and upon Sleightowen, Sleight McDonell, Sleightloghlen, Cleindonoghmore, Sleight McBrien, Sleight Mahon, Sleight Donell Clery, Sleightcossnyhown and Sleight Shane in the province of Connaught. To hold for life, remainder to Rory ne moy, his son and heir, in taile male, remainder to Shane ne moy, another son of the said Shane, and his heirs for ever.’[xli]

Fr. Egan in his book ‘The Parish of Ballinasloe’ identified some of these sub-branches of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain owing services and dues to Shane ne moye. The ‘Sleightloghlen’ he identified as the ‘Sliocht Lochlainn’ (or ‘the posterity of Lochlainn’) who were the Kellys based at Beagh in the parish of Creagh. He identified the ‘Cleindonoghmore’ (‘Clann Donnchaidh mhór’, ‘the family of Donnchadh mór) as the Kellys of Killeen in the parish of Kilcloony and suggested that the Sleight McDonell may have been the Kellys of Ballinasloe, all descendants of Eoghan finn, the progenitor of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain.[xlii]

The lands granted to Shane ne Moye comprised lands on both sides of the River Suck, and included the parish of Creagh on the east side of the Suck in County Roscommon in its entirety. In addition to other lands, he claimed the lands of Garbally (‘Garwalle’) which was Church land and held and retained at that time by the MacTullys.

The residences of Shane ne moy O Kelly

Shane ne moy had possession of three castles or tower-houses within his territory (and possibly another residence at Cloonigny in the parish of Kilgerrill) and at various times was described as seated at each. His principal castle, called Killeen, lay on the western side of the Suck in the parish of Kilcloony. The early modern denomination appears to have comprised the modern townlands of Perssepark, Killeen and Tobergrellan, with the O Kelly castle situated within the later Perssepark.[xliii] The remains of this castle was still in existence in the mid twentieth century, when Fr. Egan described it as lying beneath a heap of rubble in the garden of Perssepark House.[xliv] The site of the same castle was not recorded on any of the Ordnance Survey maps dating from the mid nineteenth century.

In addition to Killeen, he held the castle of Creagh on the eastern side of Suck, where he described a resident circa 1578 and the castle of Toamshroer or Tuaimsrurra in the modern townland of Ashgrove.[xlv] His castle of Creagh was indicated in ‘Petty’s Atlas’ of 1683 as ‘Castlecreagh’ and situated in the modern townland of Creagh by the side of the modern public road, while a substantial building was indicated on the same map, close to the banks of the Suck, as ‘Tamshuragh.’ The site or remains of this castle were not indicated on mid nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps. (The remains of an early church called ‘Templereelane’ were shown, however, in that vicinity, but these disappeared by the late twentieth century with only the earthwork traces of its boundary wall remaining.)

In 1574 he was recorded as seated at Cloonigny in the parish of Kilgerrill and while Fr. Egan gives his son Rory as holding the castles of Creagh and Cloonigny in Rory’s lifetime, neither of the inquisitions taken after the deaths of Shane ne moy or Rory or an account of the property of Rory’s son Donell specifically mention a castle in their possession in that location. (Donell was given as holding the castle of Creagh circa 1618 but only a half-quarter of Cloonigny. No mention was made at that time in the Calendar of Patent Rolls of King James I to a castle on those lands, although this source commonly lists both extant and ruinous castles.) A substantial rectangular enclosure is situated in Cloonigny, measuring approximately 48m wide and 64m long and aerial photography would suggest that a tower or structure stood within the enclosure, about the south-western boundary but this may not have been in use in 1618.

The sixteenth century English garrison at Ballinasloe

By the late 1570s and early 1580s the English administration of the province had established a strong presence at Ballinasloe, valued as a strategic crossing point on the Suck. Initially the castle of Ballinasloe on the Suck was taken in hand by the Crown and granted to Richard ‘sassanach’ Burke, 2nd Earl of Clanricarde, who ruled an extensive territory to the west between the lands of the O Kellys and the town of Galway. In 1576, after Clanricarde fell from favour (being suspected of fermenting unrest in the province), the English Lord Deputy, Sir Henry Sidney removed the castle at Ballinasloe from his control and an English constable was installed there with a garrison for the better maintenance of the English interest. Before Sidney left he had construction commenced on a bridge ‘over the great river of Sowke, hard by the castle of Balislogh’ which would facilitate easier access for troops and officials into the province.[xlvi] The same bridge was completed before March of 1579 by Sir Nicholas Malbie, who was appointed Colonel or Governor of Connacht. Captain Anthony Brabazon, Malbie’s son-in-law, came to be seated at Ballinasloe by the 1580s and acquired a large estate in the vicinity, at the expense of a number of Gaelic families, in particular the Kellys of Ballinasloe.

The Composition of Connacht 1585

To finance their administration and military presence in Connacht, the government resolved that a rent be agreed and charged from each division of land in the province. The rent would be payable to the crown, and called the Composition rent, after an agreement drawn up in 1585, between the Queens servants and the Connacht chieftains; the Composition of Connacht, effectively abolishing the various exactions and services imposed by the ruling Gaelic chieftain. By signing up to the Composition document, the signatories acknowledged their lands as private property, held under English law, in return for the agreed rent and on condition that they provide an agreed number of soldiers to support the administration when required. In so doing the signatories repudiated the Gaelic legal system in favour of that of England.

The principal men of Uí Maine, in agreeing to the Composition arrangement, agreed to the abolition of the Gaelic chieftaincy of Uí Maine held at that time by the then O Kelly, Hugh of Lisdalon.[xlvii]

The Indenture of O Kelly’s County, made between the Queen’s representative and the foremost men of Uí Maine ‘on both sides of the river of Suck in the province of Connaught’ included ‘Shane ne moye O Kelly of the Criaghe, gentleman’ among the participating parties.[xlviii] That indenture recognised the territory of ‘Imanny (Uí Maine) called O Kellie’s Country’ as containing five baronies and gave the territory of ‘Clonmacknoyne, otherwise Shane ne Moye’s country on both sides of the Succe’ as located within the barony of Moycarn.’ (Clonmacnowen would later be established as a half-barony in its own right.)

The Butler Earl of Ormond re-asserted his family claim to the medieval Butler lands at Aughrim in the late sixteenth century and had his claim to those lands confirmed under English law, forcing the prominent branch of the Kellys who had held these lands for several centuries to rent their lands from Ormond. Despite Ormond’s ancestor’s previous title to the manor of Suicin about Ballinasloe, the Clann mhaicne Eoghain retained possession of those lands in the late sixteenth century.

Property and dues of Shane ne moy O Kelly

For the latter years of life Shane ne moye O Kelly was described as seated at ‘Kyllen’ (recte: Killeen).[xlix] He died in November of 1585 and was survived by his widow Cecilia ny Donelan and at least three of his sons. An inquisition taken about three months after his death into the extent of his property and dues revealed not only his extensive lands but that he was still in receipt of the services and dues from sub-septs within Clonmacnowen in accordance with the ancient Gaelic custom. The juror’s findings suggest that while the nature of the exactions may not have been specific. He ‘exacted and demanded from these families his expenses every time he went to Dublin or any other large town.’[l] The families in question were given as the ‘Sleuight Donyll,’ ‘Sleuight McOwen’, ‘Sleight Loghlin’ and the ‘Clan Mulrony’, all of whose lands lay on the eastern side of the Suck in County Roscommon. Of these the ‘Sleuight Donyll’ (ie. the Kellys of Ballinasloe) held the greater extent of land under Shane ne moy, amounting to fifteen quarters. On the western (County Galway) side of the Suck he derived rents from ‘the sept called Clan Donoghmore,’ ‘Sleight Donell Clery,’ ‘Sleught Bryan,’ ‘Sleught Maghon’ and the ‘Sleight Cosny Howne.’ Of these the ‘Sleught Bryan’ may have held the greater extent of lands, amounting to nine quarters. As his sons would not be in receipt of the exactions from the eastern families or rents from the western families, Fr. Egan suggested that these expired on his death, in a similar way to which the rent due from Clonmacnowen to the O Kelly chieftain of Uí Maine, Hugh of Lisdalon, would expire on the latter’s death.[li]

Immediately prior to his death Shane ne moy was seised in fee, on the eastern side of the Suck, of ‘the Castle of Toamshroer (modern townland of Ashford) and of one quarter adjacent with appurtenances.’ He also held ‘the castle called Creagh and one quarter adjacent with appurtenances and of a half-quarter in the town, village or hamlet called Carrin, and of a half-quarter in the town, village or hamlet called Cornaservog (modern townlands of Gortnasharvoge and Cloonabrack) and of a half-quarter in the town, village or hamlet called Kyllen Mulrony (modern townlands of Cuilleen, Tonlemona and Attirory) and of one cartron or the half part of a quarter with appurtenances in the town, village or hamlet called Kylbegla (Kilbegly, in the parish of Moore, adjacent to Creagh) and a half cartron of land, viz. an eighth part of a quarter with appurtenances in the town, village or hamlet of Kylgarrow,’ (modern townlands of Kilgarve and Portnick, with part of the ‘Townparks’ of Ballinasloe town) all held by letters patent of the Queen in capite by knight’s service and ‘afterwards to his son Rory and his heirs male and in defect of such heirs to John Burke, Viscount Clanmorris for a term of eighty years.’[lii]

Rory was also heir to Shane ne moy’s property on the western (County Galway) side of the Suck, most of which lay in the parish of Kilcloony and north into those parts of the parishes of Kilgerrill and Ahascragh in Clonmacnowen. There, Shane ne moy was seised in fee taile male ‘of the Castle of Kyllen and of two quarters of lands of various kinds, (the modern townlands of Perssepark, Killeen and Tobergrellan) and of one quarter with half a quarter in Downeloe (modern townland of Dunlo) and of three parts of a quarter in the town or hamlet and lands of Garvally (Garbally) and of half a quarter called le Lurge (the hill near Ballinasloe whereon this part of the inquisition was taken), one cartron and half a cartron in Caldraghlee (modern townlands of Deerpark and Eskerroe), one cartron in Knock Ro (Knockroe), half quarter in the town or hamlet of le Shean, half quarter with appurtenances in Downgogan (modern townland of Dundoogan, parish of Kilgerrill), one cartron in Cowlenegore, half quarter in Kylbelardagh (‘Killvolagh’ in Kilgerrill parish), a sixth part of a quarter in Kyllaremore (modern Killuremore, parish of Kilgerrill, adjacent to Kilcloony), half quarter in Clyard, one quarter called Cormucklagh, two cartrons of Kylglass, half quarter in Ballyeughtar (modern townlands of Cornamucklagh, Kilglass and Ballyeighter in the parish of Ahascragh), half quarter called Caldragh Killuremore, one quarter called le Grandge (possibly Grange in the parish of Kilcloony) and one cartron and half of a cartron in Kyl-b-y.’ [liii]

When Shane ne moy had surrendered his lands to the Crown in 1578, some of those lands had included Church lands long in use or detained by the O Kellys. After the translation of Stephen Kirwan to the Clonfert diocese as Reform (or ‘early Protestant’) Bishop in 1582, Captain Anthony Branbazon obtained a lease in perpetuity of thousands of acres of Church lands in the parishes about Ballinasloe from Bishop Kirwan, including lands at ‘Tuaimsrurra’ (modern townland of Ashford) in the parish of Creagh. There Shane ne moy held a castle and had claimed the entire parish of Creagh in his surrender of 1578, but Brabazon’s lease of these lands significantly increased his holdings locally at the expense of some of those long-established families such as the O Kellys.[liv] In an inquisition taken into the extent of Brabazon’s lands in 1604, a number of years after his death, Brabazon was found to have possessed ‘the ruined Castle of Tuam Srower and of the quarter of the same name upon which the said castle is built’ among other lands formerly held by Shane ne moy. Both Rory and Shane oge, sons of Shane ne moy, were among at least eight persons who claimed lands that Brabazon held in his possession. The quarter of Tuaimsrurra was held in its entirety by the late 1630s by the Bishop of Clonfert.

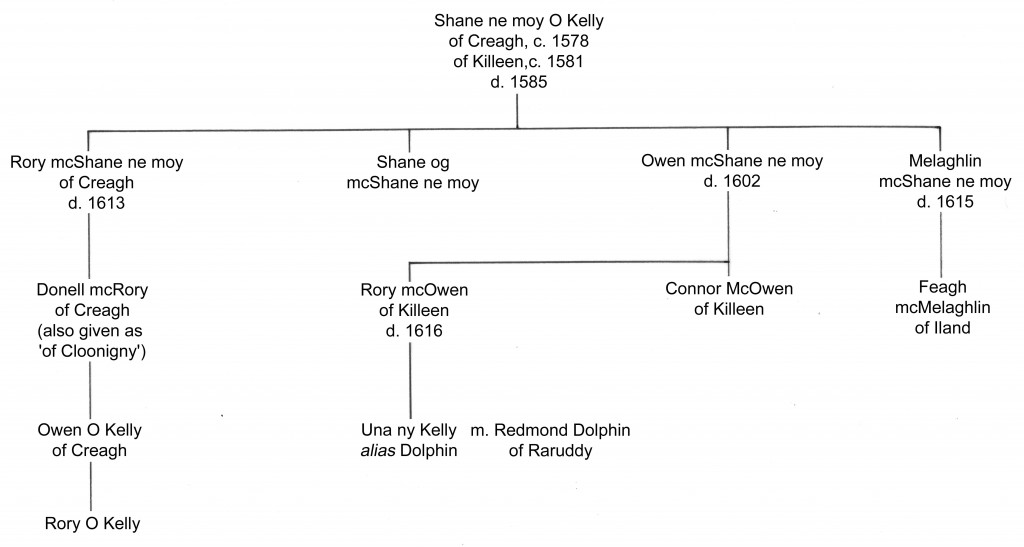

Immediate family of Shane ne moy

Shane ne moy had at least four sons; Ruaidhri (or Rory mcShane na Moy), Shane oge, Eoghan (or Owen) and Mellaghlin (or Malachy) and at least two daughters; Mor, who was married to Donal O Madden, last chieftain of Síl Anmchadha and Onora ne moy, who was pardoned by the Crown alongside her sister and brother-in-law and a number of O Fallons in 1581.[lv]

In 1581 ‘John alias Shane ne moy O Kelly of Killen, County Galway’, together with ‘Rory mcShane ne moy O Kelly, Mallachie or Mellaghlen mcShane ne moy O Kelly and Shane oge mcShane ne moy O Kelly’ all of ‘Killen’ were foremost among a number of individuals of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain who were issued a pardon by the Crown in 1581 on the recommendation of Sir Nicholas Malbie, then governor of Connacht and Thomond.[lvi] Shane ne moye’s son Eoghan was not among those issued a pardon on that occasion.

The senior line of Rory mcShane ne moy of Creagh

Rory as his heir would appear to have been the eldest surviving son of Shane ne Moy and was described as ‘Roger alias Rory McShane na Moy’ and ‘Rory O Kellie of Creagh’ at his death. He died in about January 1613 and after his death an inquisition taken into the extent of his lands on the Galway side of the Suck found him to have been proprietor of half a quarter in ‘Cloon Ingny’ (ie. modern townland of Cloonigny) in the parish of Kilgerrill and one cartron of ‘Cleymore alias Cohrmore’ (modern townland of Cleaghmore) in the parish of Kilcloony. From a later account of his son’s lands it is apparent that he held other lands across the Suck in Creagh, which were in all likelihood detailed in a separate inquisition.

Rory’s heir was his eldest son Domhnall or Donell, who held lands on both sides of the Suck. About 1618 as Daniel McRory O Kelly of Creagh, gentleman, he was confirmed in possession of the half quarter of ‘Cloinguy alias Sighane’ (Cloonigny), a half quarter of ‘Dungroagin’ (Dundoogan), both in the parish of Kilgerrill and one cartron of ‘Corhoure (ie. Cleaghmore); parcel of the four quarters of Dunleo. These lands formed his estate on the County Galway side of the river and on the other he held the castle and a half quarter of Creagh and one cartron of ‘Caldraghereagh or Glanton’ (modern townland of Glentaun), all in the parish of Creagh in the half barony of Moycarn.[lvii] In 1629 Donell McRory made over his lands in Cleaghmore in perpetuity to William Tully of Cleaghmore.[lviii]

The lines from the junior sons of Shane ne moy

Eoghan (or Owen) would appear to have been the second surviving son of Shane ne moy, given the extent of his inheritance when compared with that of his brothers. All of his property lay on the western side of Suck. He held a half share of the castle of Killeen and lands in that quarter, together with lands called Lisdony in Clunsaile, lands in ‘Donleo in the quarter of Caldragh’ and in Garbally, all in the parish of Kilcloony. In the parish of Kilgerrill he held lands in the denomination of Kigerrill itself, Killveilaha (‘Killvolagh’), in a part of the denomination of Killuremore called Garrinegrallagh. He held a parcel of land in a part of the denomination of Cregan called Shanbally (modern townland of Shanboley, adjacent to that of Creggaun) in the parish of Ahascragh and a parcel called Glinan in Gortcarne in the parish of Clontuskert. He died in March 1602 and was succeeded by his son Rory McOwen.

This Rory McOwen O Kelly of Killeen, gentleman, was 18 years and unmarried when his father died. In 1612, as part of his marriage plans with Ellen Ny Coawge, he conveyed his half share of Killeen castle and in the lands at Kylvalagh, Lisdowny, Shavally and Gortecarne to Richard McCoawge of Derrydonnell and Theobald McCoawge of Lissduff to the use of Ellen for her lifetime ‘and afterwards to the use of Rory and his heirs.’ He appears to have died at a relatively young age in April 1616, leaving as his heir his six year old daughter by Ellen Ny Coawge; Una Ny Kelly.

At his death he was seised in fee of lands in ‘Killower’ (Killure), Downloe and ‘Eyrgerrill’ (Kilgerrill). From the lands assigned to her use, Ellen Ny Coawge continued to receive profits while his mother Una Ni Tumultagh was also still alive and received as her dower a third part of all of his property.[lix] Through the later marriage of the heiress Una Ny Kelly, her father’s share of the O Kelly lands would pass into the hands of another family.

Una Ny Kelly married Redmond Dolphin of Raruddy, near Loughrea, a descendant of family settled in east Galway since the Anglo-Norman occupation and both husband and wife in 1631 demised her father’s half share of Killeen castle and the O Kelly lands at Killeen, ‘Keilveilleha’ (Killvolagh), Lissdowney, Killgerril, Gortcarne, Killuermore and Donloe to John Burke, Viscount Clanmorris for a term of eighty years.[lx]

It would appear likely that ‘Connor McOwen O Kelly of Killene, gentleman’ who possessed a half quarter of Kellin (Killeen) and lands in Lisdowny, Coilvelaha, Dunleo, Gortecharne and lands in ‘Caryownegrallagh, being a sixth part of a quarter of Killuremore’ in the parish of Kilgerrill about 1618 was a younger son of Owen son of Shane ne moy.[lxi] Another son may have been William mcOwen mcShane O Kelly, who was killed in rebellion during the wars about the end of the sixteenth century. He was declared guilty of treason and his lands confiscated and a parcel of those lands, comprising a small section of lands at Gortecharne in the parish of Clontuskert was among an extensive grant of lands extended by the Crown to the Earl of Kildare about 1609.

Shane ne moy’s son Mellaghlin (also given as ‘Malachy alias Milaghlin McShane Namoy’) appears to have been younger than Ruaidhri or Eoghan. He died in January of 1615 seised in fee of an island known simply as ‘The Island’ with a cartron of land adjacent to the same island in the half barony of Clonmacnowen. He was succeeded by his eldest son and heir Ffeogh McMelaghlin Namoy, who about 1618 as ‘Feagh McMelaghlin O Kelly of Iland, gentleman, possessed a half of Carowlumnaghtagh (Cleaghmore) and a half cartron of Knockanduin in the half barony of Clonmacnowen.[lxii]

There would appear to be little reference to Shane ne moy’s son Shane oge (ie. Shane the young) in the early seventeenth century but he was living about 1604 when he claimed part of the lands held by the deceased Captain Anthony Brabazon. He may have been the second son of Shane ne moy, given the reference made to him in line of succession in the 1578 grant to his father and may have died prior to 1618.

1641 Insurrection

With the prospect of fresh land confiscation’s and colonisation’s looming large in the background and unable to depend on an unreliable monarch or an increasingly powerful anti-Roman Catholic English Parliament for satisfaction, several of the Ulster Roman Catholic land-owners took advantage of the divisions then current between the King and English parliamentarians and in 1641 rose up in arms against the colonists. The leading rebels claimed as justification for their actions that they were rising out in support of the King, in his struggle with an English parliament determined to divest him of his powers. As the Ulster rebels, composed mostly of the Gaelic aristocratic families, claimed to be acting in the interest of the Crown, the old Anglo-Norman families or the Old English, found themselves on the same side as the Gaelic lords, facing a common enemy. Many of the Old English joined the insurgents and the rebellion met with considerable initial success.

In 1649, after the forces of the English Parliament had successfully dealt with the forces loyal to the King in England, a Parliamentary army under Oliver Cromwell was sent from England to suppress Ireland. By 1652 the Cromwellians had effectively defeated the various Irish armies and proceeded to redistribute the land ownership in Ireland in part to pay those who had financed and fought their campaigns and in part to install a new landowning class in Ireland favourable to their government.

Cromwellian period

Anthony Brabazon of Ballinasloe, grandson of the first Captain Anthony Brabazon, took a leading part in the Insurrection in 1641. As governor of Ballinasloe, he held out at his castle at Ballinasloe for the rebels until the castle was taken by the Cromwellians in 1651.[lxiii] After the final defeat of the Irish forces by the Cromwellians Brabazon was declared exempt from pardon and his castle at Ballinasloe was garrisoned by men under the Cromwellian Major Despro, who would reside there for a number of years.

In the aftermath of the war various accusations were made regarding the activities of Brabazon in his prosecution of the war, ranging from pillaging of neighbours and others supportive of the Parliamentary forces, to murder, by him or his men, of English Protestants. One case in particular with which he was accused was that of the murder of William Hughes and the wife of one Harry Collier, murdered by Brabazon’s soldiers during the siege of Athlone.[lxiv] He was similarly accused of protecting the murderers of an Englishman named Collins.[lxv] In addition it was claimed that ‘the Pope’s nuncio lay at his house in Ballinasloe.’ One of his principal accusers was Owen O Kelly of Creagh, gentleman, described by O Donovan and Fr. Egan (on the basis of O Farrell’s ‘Linea Antiqua’) as son of Donell or Daniel mcRory O Kelly of Creagh and the senior representative of the line of Shane ne moy O Kelly.[lxvi]

Reduction of the senior representative of the sept from landed proprietor to tenant

The senior-most branch of the O Kellys of Clonmacnowen, that of Donell son of Rory son of Shane ne moy lost possession of much of their lands in Counties Galway and Roscommon as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century.

Following the turmoil of that period and the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, an Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time. Under the Act of Settlement Donell McRory Kelly was confirmed in possession of lands in the parish of Ahascragh, amounting to seventy-six profitable Irish acres that had been previously allocated to him by the Cromwellians in the townland of Lunaghtaine.[lxvii]

While Donell McRory was confirmed as owner of the Lunaghtaine land, it would appear that he or his son remained at Creagh, but as tenants rather than owners. Anthony Brabazon’s widow Ellis, who married Theobald Dillon of Loughlin in County Roscommon, had retained part of the Brabazon property under the Cromwellians, while the rest was confiscated to provide for new settlers and those transplanted into Connacht. She retained part of their Creagh lands and under the Act of Settlement was confirmed in possession of the lands of Donell McRory in the half quarter of Creagh, amounting to one hundred and seventeen profitable Irish acres, which included Shane ne moy’s castle thereon.[lxviii]

Donell mcRory’s lands in Glantaun, adjoining the townland of Creagh, were confirmed upon others under the Act of Settlement, while in the parish of Kilcloony Matthew Tully was confirmed as owner of Donell’s lands in Derrymullen (and were later acquired by the Trench family). His lands in Cloonigny in the parish of Kilgerrill were allocated to the Countess Fingall, while the O Kelly lands in that parish in Dundoogan had been acquired before the Cromwellian transplantations by the Donnellans.[lxix]

Donell’s son Owen was listed in a census of 1659 as one of the principal persons of standing in the parish of Creagh, alongside Daniel Kelly of Ardcarne and Bryan of Attyfarry, but as noted by Fr. Egan, was ‘now reduced to the status of tenant to the widow of Anthony Brabazon.’[lxx]

This Owen O Kelly was born about 1614, as he was forty years of age when he made the deposition against Anthony Brabazon in 1654.[lxxi] His date of death is uncertain but the pedigree of this family in O Farrell’s ‘Linea Antiqua’ terminates in giving Owen’s son as Rory O Kelly.[lxxii]

While the property of Shane ne moy’s son Eoghan had passed from the family through the marriage of an heiress, the small estate of Feagh, son of Shane ne moy’s son Mellaghlin, comprising land in Fedan in the parish of Creagh and Carrowlumnagh (ie. modern Cleaghmore) in the parish of Kilcloony, was also taken from his ownership and confirmed upon others under the Act of Settlement. Like the senior branch descended from Shane ne moy, the minor sub-septs of the Clann mhaicne Eoghain such as those based about Killeen and Beagh were deprived of ownership of their lands also in the Cromwellian period, to the extent that the O Kellys as a family group were no longer significant landholders in what had been their ancestral territory of Clonmacnowen by the end of the seventeenth century.

Fr. Egan related the tradition, still current about Ballinasloe in the mid twentieth century, that one John O Kelly, described in the story as ‘the heir of Moycarn’ (the half-barony on the Roscommon side of the Suck wherein lies the parish of Creagh) after returned from abroad, was riding through Ballinasloe when his horse shed a shoe. The blacksmith engaged to replace the shoe was said to have spiked the replacement, laming O Kelly’s horse and thereby enabling pursuers to catch up with him atop Kilbegley Hill in the parish of Moore, where they murdered him, reputedly at the instigation of his half-brother. According to Fr. Egan, the spot was thereafter marked by a small cairn of stones. While no more than a tradition, Fr. Egan was of the view that if true, the victim would appear to have been of the senior line of Shane ne moy and the story could only relate to the period between the mid to late seventeenth century, given his description as the ‘heir of Moycarn.’[lxxiii]

Writing in the mid nineteenth century, John O Donovan in his ‘Tribes and Customs of Hy Many’ described the descendants of Shane ne moy of Creagh collectively as the ‘sliocht Seaain O Kelly’ or ‘the posterity of Shane’ but he was unable to say whether this family group had a living representative at that time.[lxxiv]

[i] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7.

[ii] Knox, H.T., The Early Tribes of Connaught: part 1, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth series, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1900, p. 349; Mannion, J., The Senchineoil and the Sogain: Differentiating between the Pre-Celtic and early Celtic Tribes of Central East Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 58, 2006, pp. 166, 168; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Leabhar na g-ceart or The Book of Rights, Dublin, M.H. Gill, for the Celtic Society, 1847, p. 106.

[iii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 97.

[iv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 98.

[v] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 98. O Donovan states that these chieftains of Ui Maine, apparently successive; Mughron son of Sochlachan, Sochlachan son of Diarmuid and Murchadhan son of Sochlachan, were all of a tribe known as the Cruffons, ‘who sank at an early period.’

[vi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 98.

[vii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 99.

[viii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 99.

[ix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 99.

[x] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 101-2.

[xi] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1903, Part v, pp. 284-5.

[xii] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1903, pp. 285-6.

[xiii] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1903, pp. 285-6.

[xiv] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1903, pp. 285-6; Egan, P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 33.

[xv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 33, 35, 39.

[xvi] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1903, pp. 285-6.

[xvii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 35.

[xviii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7.

[xix] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7; Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp. 49-53.

[xx] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 103.

[xxi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 102.

[xxii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 102; Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7.

[xxiii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7, 301.

[xxiv] Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp. 53-55, the line descended from Pilib is given by MacFirbhisigh as ‘Pilib son of Mathghamhain son of Muircheartach son of Pilib son of Eóghan son of Domhnall mór; Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7.

[xxv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7, 75, 87.

[xxvi] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 38-9.

[xxvii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7; Annals of the Four Masters.

[xxviii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 126.

[xxix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 126.

[xxx] Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp. 53-55; Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 36-7.

[xxxi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 126-7.

[xxxii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 126-7; Annals of the Four Masters.

[xxxiii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 126-7.

[xxxiv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 36, footnote 42.

[xxxv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 126-7.

[xxxvi] Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp. 53-55. MacFirbhisigh gives the sons of Seaan son of Donnchadh son of Ruaidhri as ‘Seaán ballach, Fearghal, Ruaidhri, Domhnall, Maol Eachlainn and Eóghan.’

[xxxvii] Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, p. 53.

[xxxviii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 38-9.

[xxxix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 126-7.

[xl] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 38-9.

[xli] Calendar of Fiants Queen Elizabeth I, The thirteenth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records in Ireland, 12 March 1881, Dublin, A. Thom & Co., 1881, Appendix IV, Fiants Eliz. I, p. 89, no. 3381. Coagh O Fallon of Miltown in County Roscommon, the head of the O Fallons, received a grant of his lands that same day, 26th July 1578.

[xlii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 38-9.

[xliii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 72, 315.

[xliv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 72.

[xlv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 301.

[xlvi] Sir Henry Sidney’s Memoir of his Government of Ireland (continued), Ulster Journal of Archaeology, First series, Vol. 5 (1857), p. 313-4.

[xlvii] O Flaherty, R., Ogygia: or, A chronological account of Irish events: collected from very ancient documents, (translated by Rev. James Hely), Vol. II, Dublin, W. M’Kenzie, 1793, Part III, pp. 318-321.

[xlviii] O Flaherty, R., Ogygia: or, A chronological account of Irish events: collected from very ancient documents, (translated by Rev. James Hely), Vol. II, Dublin, W. M’Kenzie, 1793, Part III, p. 318-321.

[xlix] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 301.

[l] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 301.

[li] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 72.

[lii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 301.

[liii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 301.

[liv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Royal Visitation of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, 1615, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. XXXV, (1976), p. 71; Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 47-8. ‘Captaine Brabson of Ballynasloagh Esq.’ obtained a lease in perpetuity at that time of lands in ‘Killconnill, Killcomodam, Killuir, Killcluine, Tuaimsrurra, Cluinborrin and Rahkhray.’

[lv] Calendar of Fiants Queen Elizabeth I, The thirteenth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records in Ireland, 12 March 1881, Dublin, A. Thom & Co., 1881, Appendix IV, Fiants Eliz. I, p. 140, no. 3729.

[lvi] Calendar of Fiants Queen Elizabeth I, The thirteenth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records in Ireland, 12 March 1881, Dublin, A. Thom & Co., 1881, Appendix IV, Fiants Eliz. I, pp. 139-140, no. 3720.

[lvii] Calendar of Patent Rolls, 16 James I, p. 417, dated 28th November 16th.

[lviii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 302-3.

[lix] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 302-3.

[lx] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 302-3.

[lxi] Calendar of Patent Rolls, 16 James I, p. 418, dated 28th November 16th.

[lxii] Calendar of Patent Rolls, 16 James I, p. 418, dated 28th November 16th.

[lxiii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 83.

[lxiv] Trinity College Dublin, Ms. 831, fols. 279r-280v. Deposition dated 28th June 1653.

[lxv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 85.

[lxvi] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 85-6; O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 126-7.

[lxvii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 131, 146.

[lxviii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 87-8. Brabazon’s daughter Sara was allocated lands Tumsrura and Edward Brabazon lands in Beagh, all in the immediate vicinity of Ballinasloe.

[lxix] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 131-2.

[lxx] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 88-9.

[lxxi] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 85-6.

[lxxii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 126-7.

[lxxiii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 85-6.

[lxxiv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 126-7.