© Donal G. Burke 2013

A brief history of O Madden’s country in East Galway

Continued from ‘Thirteenth century.’

Richard de Burgh, the Red Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht

While the start of the new century saw the Red Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht engaged in consolidating his lordships and erecting castles at various strategic locations, the early years of the century also witnessed Richard de Burgh suffer personal loss. His brother Theobald died at Carrickfergus on Christmas eve 1303 after returning with the Earl from an expedition to aid the King in Scotland. Within a short time of one another, his wife Margaret and his eldest son and heir, Walter, died in 1304. Nine years later, his next eldest son and heir John, married to Elizabeth de Clare, would also predecease his father.

Affairs in Scotland impinged on the affairs of Ireland with the Earl participating in a number of expeditions as part of the King of England’s forces. Elizabeth de Burgh, the eldest daughter of the Red Earl, was married to Robert de Brus or Bruce, a Scottish aristocrat of Anglo-Norman descent who harboured a claim to the kingship of Scotland but at the time of his marriage to the earl’s daughter was still siding with the King of England in his wars in Scotland. In the spring of 1306 Robert Bruce was proclaimed King of Scotland but his wife, the Earl’s daughter, was held a prisoner by King Edward I in England.

O Madden and O Kelly and Sir William liath de Burgh

The Anglo-Norman presence in the easternmost region of the later County Galway side by side with the native Irish is evidenced by the remains of various mottes and moated sites about the area and in the survival of such placenames as Corballynagall (ie. Corbally of the ‘Gall’ or ‘Foreigners’) about Abbeygormacan on the western border of Síl Anmchadha, about which the Anglo-Norman de Valles or Walls held lands.[i]

In the east of the Connacht lordship, the head of the O Maddens, like many of the Gaelic lords within the Earl’s dominion, when called upon, was required to answer the Earl’s summons like any other vassal and attend upon him with his armed followers to assist the Earl in his wars. In 1308 Eoghan (or ‘John’) O Madden was in the company of Rory O Connor and Tadhg O Kelly and such prominent Anglo-Normans of the Connacht lordship as Thomas Dolfyn, Geoffrey de Valle, Philip Haket and Richard le Blake who attended with men at arms upon Sir William liath de Burgh, then serving as Deputy Justiciar, on a military expedition on the king’s behalf against the Irish of Leinster.[ii]

The power of Sir William liath and the trust placed in him by the Earl may be gauged by the Irish annalists report on the political situation in Connacht after the slaying of Aedh O Connor by his own constable, at the instigation of Sir William liath, in 1309. ‘Connacht was without a king for the greater part of a year after that, being under the sway of William de Burgh. And the said William gave the title of king to the son of Aedh.’[iii]

In 1314 Eoghan O Madden and Tadhg O Kelly were again on the same side, as allies of Murtagh son of Turlough O Brien, Sir William liath de Burgh’s candidate for the kingship of Thomond in his struggle against Donagh O Brien, the candidate supported by de Burghs opponent, Sir Richard de Clare. It is also likely that several of the leading Gaelic families of Sil Anmchadha formed part of the Gaelic contingent of the Red Earls forces on the various occasions he served the King in his wars in Scotland at the end of the thirteenth and start of the fourteenth century.

Edward Bruce in Ireland

In 1315 Edward Bruce, brother of the Scottish king, Robert Bruce, landed in Ulster, and many of the native Irish flocked to his banner. The Red Earl gathered a great force of his Anglo-Norman and Gaelic allies and vassals at Roscommon, including Felim O Connor King of Connacht and marched to engage Bruce. Sir William liath was with the Earl in the campaign, leading a small party who sought to catch Bruce by surprise about Louth.

Bruce covertly induced Felim O Connor to leave the Earl’s forces while Felim’s rival Rory, brother of Aedh breifneach, seeing so many of his rivals supporters out of Connacht at the time saw an opportunity to make a grab for power. Rory also held negotiations with Bruce and offered to push the Anglo-Norman out of Connacht, to which Bruce agreed with the proviso that Rory not trespass or plunder the lands of Felim.

Rory, however, while Felim was still with the Earl, gathered his allies and mercenaries and struck deep into Sil Murray and on into the rest of Connacht, burning all in his path including Dunamon, Roscommon, Rinndown and Athlone and had himself proclaimed king at the traditional site of Carnfree. Rory and his men left the Earl’s army on learning of Rory’s actions but found himself unable to oust Rory.

When Felim’s men left the Earl’s camp, the Red Earl’s forces were obliged to retreat to the castle of Connor, where they suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of Bruce in September 1315. In the battle of Connor O Neill and the Irish of Ulster, together with the Scots, took the Earl’s forces by surprise and, while several prominent Scots knights fell, the Scots won the field. Sir William liath de Burgh was taken prisoner and an account written a month later reported that he was ‘said to have been sent to Scotland.’[iv]

The Earl repaired to Connacht, which was thrown into turmoil as the O Connors took full advantage of the situation and where the Irish swept across the lordship devastating Anglo-Norman settlements. The Butler castle and lands at Aughrim in the cantred of Omany was burned and Rory O Connor burned de Bermingham’s castle at Dunmore. [v] Tadhg O Kelly burned and plundered the Earl’s own cantred of Maenmagh about Loughrea, while the Earl, rendered politically and militarily impotent following his defeat and bereft of support, was left ‘a wanderer up and down Ireland all this year with no power or lordship’[vi] To him repaired a number of Gaelic chieftains who had previously been loyal, such as O Madden of Sil Anmchadha and who were now ousted by their rivals who supported Felim.

The following year Felim assembled a large force of his own supporters, including his MacDermott foster-father, de Bermingham and others to fight Rory and contest the kingship and in February ‘on the moor of Tochar’ Felim defeated Rory. He immediately seized the kingship, plunders Rory’s supporters and took hostages of the O Kellys, O Maddens and other chieftains of Connacht. He then turned on the Anglo-Normans of west Connacht, killing a number of the leading knights of that territory. Having imposed his will on north Connacht he made for the Anglo-Norman castle of Meelick on the Shannon in east Galway. There he met with more of his allies and burned and broke down the castle and made for Roscommon to destroy that settlement.[vii]

In the Summer of 1316 Edward Bruce was inaugurated as High King of Ireland by his Irish followers. The Anglo-Norman settlements across Connacht were being ravaged by the resurgent Irish, while the Earl found himself at a loss to adequately respond. The Earl diverted several supply ships intended for the support of Coleraine to ransom his kinsman Sir William liath from the Scots and by the beginning of Autumn Sir William liath was back in Ireland and made for Connacht with a band of soldiers led also by de Bermingham and other Anglo-Normans of Connacht. His arrival was recorded as significant by the annalists, who say that Felim immediately called upon his subjects to expel de Burgh and assembled for that purpose a large army across the region between Assaroe and Sliabh Aughty. The strength of this army assembled by Felim may be gauged from the presence of his O Brien allies from Thomond in Munster, the king of the Irish of Meath and the king of the Irish of Breffni in addition a wide array of O Connor’s own Irish followers of Conncht such as the O Kellys of Ui Maine.[viii]

The battle of Athenry 1316

Felim marched to de Bermingham’s town of Athenry in east Galway to oppose the Anglo-Norman force. The two armies met in front of the town on the 10th of August and in the ensuing battle Felim O Connor was killed. The defeat was a heavy blow to the Irish of Connacht, in which Tadhg O Kelly, chief of Uí Maine together with twenty-eight of the ruling house of the O Kellys were killed. Members of almost every ruling house of the Irish in Connacht lost leading individuals. Of those families of east Galway, other than the O Kellys, who lost leaders were rebels of the O Maddens, O Concannon and others, including MacEgan, O Connor’s brehon.[ix]

The thirteenth century hall-keep of Athenry Castle.

It was Sir William liath who took the leading role in re-establishing de Burgh dominance in Connacht in the wake of the battle of Athenry. With the Gaelic forces of those opposed to the de Burgh’s spent in Connacht, Sir William liath brought a large force into Síl Murray and imposed his will on the surviving O Connors and their allies. The victory at Athenry was such that it was said the victors were able to significantly add to the walled defences of the town from the profits derived from the weapons and equipment of the defeated dead.

A new pliant O Connor King was set up by the de Burghs in Connacht but in Ulster Edward Bruce still maintained a dominant position, holding court in de Burghs former castle of Carrickfergus. Having sought the practical support of his brother from Scotland he took to the field again in 1317 but achieved little of lasting significance. He and his brother Robert were confronted by the Red Earl in Leinster but the Earl was forced to retreat to Dublin, where he was followed by the Scots. Doubts persisted concerning the Red Earls determination to oppose the Bruce brothers and the mayor of that town, fearing that the Earl would surrender the town to Bruce, imprisoned the Earl in Dublin Castle. The Scots, however, lacking the necessary provisions for a siege, withdrew and continued into Munster, returning later to Ulster. Richard de Burgh languished in the Dublin prison for four months before he was released in June by the King’s order under humiliating conditions.

The following year Edward Bruce launched another campaign south but was defeated and killed at Faughart near Dundalk. His invasion coincided with successive years of famine and disastrous weather in Ireland and that, combined with the widespread destruction of crops and property caused by the wars, left the lands of much of the Anglo-Norman lordship of Ireland waste and further depleted of colonist tenants on the ground for some time thereafter.

The Red Earl, back in power after the final discomfiture of Bruce, set about attempting to restore his authority across his lands and Eoghan O Madden was among those rewarded by the Earl for his loyalty during the Bruce wars. The Earl had a grant of English common law extended to Eoghan, his brothers, a nephew and their heirs in 1320. These grants were given out in a new policy to reconcile the Gaelic Irish lords to the Government, enabling them to appeal to the English courts for justice. On parchment, the Earl also entered into a treaty with O Madden, granting O Madden one third of Connacht, with ‘no English stewards to preside over his Gaels, and he and his free clans to be equally noble in blood with his lord de Burgo.’ In practice, the O Kellys proved to be a resilient force in Uí Maine, and not only did the O Maddens actual territory remained confined to Síl Anmchadha but the Butlers failed to re-establish themselves in their lands of Uí Maine in the immediate aftermath of the Bruce defeat. Nonetheless, the head of the O Maddens was left in a strong position within his immediate ancestral lands by the following decade by virtue of this grant.

The death of the Red Earl and Sir William liath de Burgh

In 1324 the powerful figure of Sir William liath de Burgh died and two years later, in 1326, after a controversial life, ‘Richard Burke, the Red Earl Lord of Ulster and Connacht and the best of all the Galls of Ireland, died …before the feast of St. Peter ad Vincula.’ His eldest son Walter de Burgh having died in 1304 and his second son John in 1313, the Earl was to be succeeded by John’s underage son William, a minor at his grandfather’s death. The de Burgh estates yet again reverted into the King’s hands until the heir came of age. Taking control of the lands was not straightforward and Walter de la Pulle, the Escheator for Ireland, was allocated expenses in the year of the Earls death ‘because of the danger of the ways in bringing men at arms with him to the parts of Connacht, Limerick and Tipperary to take the lands and tenements of Richard de Burgh, late Earl of Ulster, into the kings hands.’ [x]

The death of Sir Walter de Burgh

During the minority spent in England of the Red Earl’s heir, William de Burgh, to be known as the Brown Earl of Ulster, Sir William liath’s eldest son Sir Walter de Burgh established himself as a powerful figure within the de Burgh lordship. Sir Walter pursued his own vigorous policies that in certain areas were directly opposed to those pursued by the young Earl, who came of age and took control over his lands in the autumn of 1328. While occasionally supporting the Earl, Walter and a number of his brothers, a generation older than the Earl, continued to assert their own schemes independent of the Earls, harrying Turlough O Connor of Connacht who had the recognition of the King of England and the support of the Earl and the Earls uncle Sir Edmund de Burgh, the Red Earl’s son. After blatantly opposing the Earl against O Connor, the Brown Earl had Walter and his brothers Edmond Albanach ‘the Scotsman’ and Reymond de Burgh taken captive and Walter was allowed to starve to death in the Earl’s Ulster castle of Northburgh in 1332. Walter’s body was thereafter brought back to Connacht and buried alongside that of his father in the presbytery (the chancel or ‘sanctuary’) of the church of SS. Peter and Paul at the Dominican friary of Athenry.[xi]

The murder of the Brown Earl

In retaliation for the death of Walter, his sister, married to one of the Earls chief Anglo-Norman tenants in Ulster, connived with members of her husbands family, the de Mandevilles, and a number of others, to avenge her brother and in 1333 the conspirators had the twenty-one year old Brown Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht murdered.

The Earl had no son, but three young daughters, his heiresses, who were soon after taken by their mother to England. All three, Elizabeth, Margaret and Isabella were minors at the earl’s death and only Elizabeth appears to have survived infancy.[xii] A bitter interfamilial feud broke out among the de Burghs. Several powerful junior branches of the de Burgh family were well established in Connacht, and these went to war with the dead earls uncle, Sir Edmund de Burgh, who was given a lease of the Connacht lands during the minority of the Brown Earl’s daughters. With the sudden loss of the Earl without a male heir and infighting among the leading members of the family, the principal lordship in Ireland began to crumble. In Ulster, the powerful O Neills, along with the Maguires and O Cathains broke free of the Crown, and in the turmoil that followed in Connacht, the native Irish such as the O Maddens, began to expand and regain lost ground.

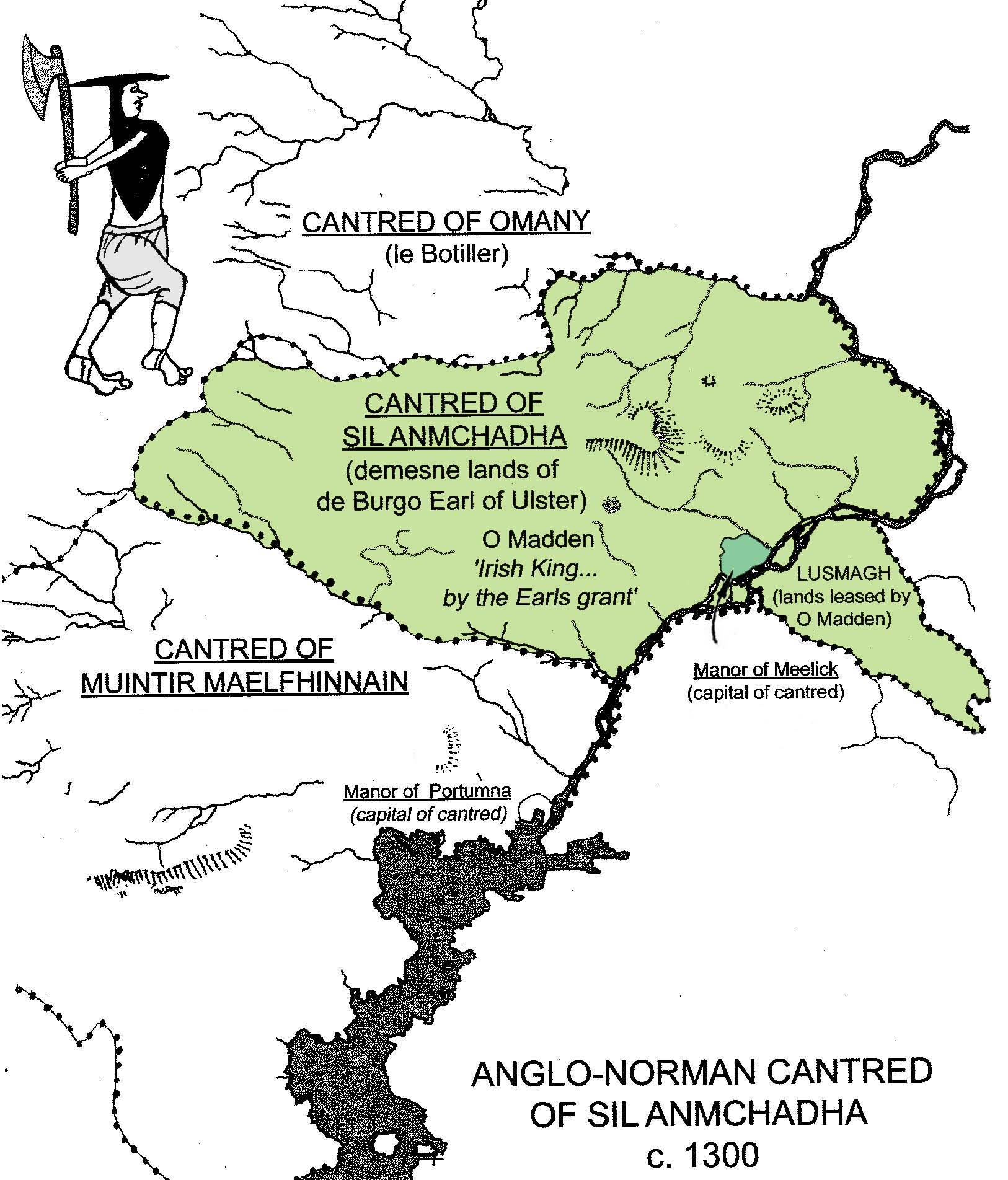

The cantred of Síl Anmchadha or ‘Syllanwath’ circa 1333

The Anglo-Norman presence in Síl Anmchadha at the time of the Earl’s death was recorded in an Inquisition Post Mortem, a survey of the entire lordship, undertaken by the Anglo-Norman administration to enable the Crown assess the extent of the late Earls property and dues. The inquisition revealed a lordship under pressure in certain areas from a well-entrenched Irish nobility and with a significantly diminished value.

By 1333 the cantred of Sil Anchadha or ‘Syllanwath’, then part of the Anglo-Norman manor of Loughrea, had lost almost two thirds of its former value.[xiii] In the Post Mortem, two principal Anglo-Norman tenants were recorded in Síl Anmchadha, Geoffrey de la Vale and the heirs of Henry Crok. A townland in ‘Leswagh’ was among the lands held in fee by de la Vale and would appear to equate with Lusmagh on the eastern side of the Shannon across from Meelick.[xiv] Meelick castle was described by the jurors as being ‘enclosed by a stone wall, and is part of the manor of Loghry (recte: Loughrea). In it are a stone chamber, with a chapel annexed, and a kitchen which is ruinous, together with other ruinous houses, which are worth nothing beyond the repairs, because they need large repairs.’[xv] The borough at Meelick was still there at this time, which the burgesses held in fee and was worth six pounds.

Two granges or monastic farms were mentioned in Síl Anmchadha at ‘Monbally’ but these were worth little owing to the amount of repairs needed to the properties.[xvi] Also mentioned were several areas of ploughland and wasteland, a weir, fishery and waterwheel.[xvii]

Within Síl Anmchadha, the head of the O Maddens, described by the inquisition jurors simply as ‘Omadan, king of the Irish of that country’ held the status of a free tenant, effectively a free man whose lands were usually held by knights service, the tenure of which were protected by the Crown of England. In the inquisition of 1333, O Madden held lands in Síl Anmchadha about Timsallagh in the parish of Kilquain (or later Quansboro) and at Killyncathall. O Madden was described as owing monies from a third part of one townland in ‘Townsillagh’, but in 1333 nothing could be gained from him from that townland as he ‘holds it in hand, but does not trouble to pay anything.’[xviii] Another of the native landholders, one Molrighlyn M’Lok’n (possibly one Melaghlin MacMelaghlin O Madden) held lands in Síl Anmchadha about ‘Kenkill’, which has been suggested as the townland of Cankilly in the parish of Clonfert.[xix]

Elsewhere in the cantred, monies were formerly derived from the betaghs of seven townlands in ‘Moyfyn’ but ‘now nothing can be got, because they lie among the Irish of Omani (ie. ‘the O Kellys and others) who occupy the said lands by the strong hand.’ The Earl’s grant of privileges to O Madden likewise strengthened his position in the territory and while certain betaghs in the cantred formerly owed livestock to the lord with a certain value and services, it was found that in 1333 they now did not pay anything as they were ‘under O Maden, an Irish king of that country, by the Earl’s grant by his letter.’[xx] Likewise, the value to the heir to the lordship of the ‘Pleas and perquisites of the Court of Silanwath’ were significantly diminished from their former worth because ‘William, late Earl of Ulster’, granted the same to O Madden for life.

Excluding various prominent members of the wider de Burgh family, among the other principal Anglo-Norman tenants elsewhere in the easternmost region of the Connacht lordship at the time of the 1333 Inquisition, Thomas Dolfyn was tenant of lands about Rathgorgyn, Kilnegolan and Rathnethan in the cantred of Maenmagh (a wide region about Loughrea). Walter Husee held lands, it would appear, about Kiltullagh, while other tenants about that cantred were given as Philip Baron, Thomas son of Eustace, Walter Erle and Walter Broun.[xxi] About Athenry the de Berminghams served as chief tenants. Further to the south east of Connacht, in the cantred of Muintir Mailfinnain, with the exception of de Burghs, the only named principal tenant was one Peter Polay at Kilmocorok, which may equate to the parish of Kilmalinoge, north of Portumna. At locations such a Meelick, Loughrea, Monbally or Kilcorban, various unnamed demesne tenants and betaghs of de Burgh were also present in the landscape.

Decline of the Anglo-Norman settlement in Síl Anmchadha

The borough of Meelick itself, it would appear, was destroyed or fell into decline shortly after 1333 by the Native Irish in the wake of the Earls murder and the Anglo-Norman colony in Síl Anmchadha failed to recover in the face of a resurgent Gaelic aristocracy. The O Maddens regained effective overall control of their ancient patrimony, made easier by the paucity of significant Anglo-Norman landholders based in the cantred, and took possession of de Burghs castle at Meelick. Unlike the town that grew up around the monastic foundation at Clonfert, the borough of Meelick was an Anglo-Norman creation and an integral part of the Connacht lordship, dependent on a significant local Anglo-Norman military presence and the order imposed by the Earl’s administration for its survival. The fall of the castle and manor to the O Maddens sealed the fate of the Meelick settlement. With regard to the de Croks and the thin veneer of a locally based knightly class, their estates appear to have been consumed by the Gaelic resurgence and they thereafter disappear as a significant presence in the cantred landscape.

Despite the setback to the English colony, expansion beyond their traditional borders was not an option for the O Maddens. To the north of Síl Anmchadha the Butlers, while retaining title under English law to their lands, were forced to relinquish physical control of their estates about Aughrim in the lordship of Uí Maine to the rejuvenated O Kellys. To the west and southwest the O Maddens were bordered by cadet branches of the de Burghs or Burkes, ready to assert their military and political strength to maintain their position and such Anglo-Norman families as the de Valles or Walls and Dolphins.

In the ensuing violence, the Connacht de Burghs carved out for themselves their own local territories from the disintegrating lordship, side-by-side and vying with, the native Irish aristocracy in relentless power struggles. They consolidated their power principally about the lands on which they themselves were settled, and so, those lands further from their political centres, over which they formerly held sway, but maintained only a lesser presence such as Síl Anmchadha, fell prey to the advances of hostile neighbours or their former Gaelic lords. Only one of the Brown Earl’s heiress daughters, Elizabeth, lived to a marriageable age, and through her marriage the vast de Burgh lands, under English law, passed into the hands of her husband and, through later marriages, into the hands of the English Royal family. Elizabeth de Burghs husband and his heirs were, in law, the lords of Connacht, but the de Burghs position was unassailable and they remained the dominant power in Connacht

O Madden and the Gaelic resurgence

By the mid to late fourteenth century the O Maddens had regained control over their ancestral lands of Síl Anmchadha, the extent of the territory altering little from this period to the middle of the seventeenth century.

Over the fourteenth century the lack of a sustained effort by the English Crown to expend funds on shoring up their Irish Lordship, much of which were diverted towards their campaigns in Scotland and elsewhere, lent itself towards a further lessening of recourse by its subjects to a central government unable to deal with the decline of their colony. The Anglo-Norman colony in Connacht did not immediately cut its ties with the Crown to which it owed feudal allegiance, but the lack of a strong central authority meant that it would be necessary to assert themselves by force to maintain their position than have recourse to an English law that did not have a strong representative in the west. Violence increased as both Anglo-Normans and Gaelic Irish also saw an opportunity to further their own political and territorial ambitions in this absence.

The King of England still sought the support of his Irish-based feudal vassals to assist in his foreign wars. While peace was proclaimed by the Kings representatives at the outdoor assembly area of Rathsecer in 1333 to the younger brothers of Sir Walter who had supported their brother in his flouting of the Kings policy under the Brown Earl, internal strife between senior members of the de Burghs would leave Connacht in turmoil for much of the century.

The conflict between the party led by the Red Earl’s son Sir Edmund and the party led principally by Sir William liath’s sons Sir Edmund Albanach and Reymond de Burgh resulted in the Red Earl’s son being captured and, with a stone tied around his neck, drowned in Lough Mask. Uncertain of the extent to which punishment for this crime would be pursued by the King, Sir Edmund Albanach gathered a fleet of ships together and withdrew further out of reach. The King, however, acknowledged the reality of the situation on the ground and still continued to treat with Sir Edmund and his brother. In August of that same year the King issued a ‘grant to Edmund de Burgh and Reymond, his brother, of sufferance for two years in respect of their adherence to certain opponents and rebels against the king in Ireland in the past, inasmuch as laudable testimony is now given as to their bearing towards him and his people there for some time.’[xxii] The brothers not long thereafter re-established their position in Connacht and, in consideration of their recent loyalty, secured a pardon in 1340 from the King for their part in the murder. Four years later the King wrote to ask Sir Edmond to supply twenty men at arms and fifty hobelers (light mounted men) for the war against the King of France and in 1347 wrote to Sir Edmond and Reymond to come to help him in the war against France and to bring ten men at arms and sixty hobelers.

Throughout this period Sir Edmund grew in power and in 1342 deposed the O Connor king with whom he had been contending for some time and with his allies set up a new king, Aedh O Connor. The dominance of Sir Edmond and his brothers within Connacht was also opposed, however, by the immediate descendants of the Red Earl and the descendents of the Red Earl’s younger brothers Hubert and John de Burgh, who were established in southern Connacht, known as the Clanricard or ‘family of Richard’ and also by the de Burghs of Munster. While Edmunds influence was stronger closest to his base in north Connacht, the Clanricard de Burghs exerted more influence in south Connacht and maintained an on-going enmity with their near neighbours to the east, the O Maddens and O Kellys. In 1343 Cathal O Madden ‘the most distinguished of his own tribe for hospitality and renown’ was killed by the Clanricard.

The Clann Riocard Burkes, O Madden’s principal enemies to the west

The de Burghs or Burkes as they came to be known across Connacht and Munster, while not formally renouncing allegiance to the King of England, possessed their estates, and drew an income from them, that under English law was due to the heiress of the Brown Earl and her husband, King Edwards younger son, Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence. In 1347 Lionel was created Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht but was not in a position to fully benefit from the incomes that were his due. Being an absentee he had little sway west of the Shannon and at a distance there was little he could do to enforce his rights. That year both rival houses of the de Burghs, that of Sir Edmund and of the Clanricard submitted to the Crown’s representative but the reality on the ground did not alter.

The O Maddens, as enemies of the Clanricard, tended to ally themselves with the Clanricards principal rival, Sir Edmond Albanach. In 1355 the O Maddens killed a prominent member of the Clanricard. Richard óg de Burgh responded that same year in an attack on Sir Edmond and his O Madden allies, with sixteen chief men of the Síl Anmchadha among those killed. The continual warfare between both de Burgh factions was regarded as responsible in part to the failure in 1357-58 of the heiress Elizabeth de Burghs officials to collect any income from Connacht. ‘No one’, it was claimed ‘dared to come there on behalf of the lady because of the war between Edmond de Burgh and Richard de Burgh.’[xxiii]

The term Clanricarde appears to have applied solely to the descendants of the Red Earl’s sons Hubert and John de Burgh up until the middle of the fourteenth century. By 1355 it appears that Richard og de Burgh, grandson of Sir William liath’s son Richard, allied himself with the Clann Riocaird. In doing so he appears to have gained prominence among that faction and attained a leadership role.

Although the original Clann Riocaird were a more senior line in genealogical descent from the Earls of Ulster than the line of Sir William liath, the leadership position attained by the descendants of Sir William liath’s son Richard among the original Clann Riocaird ensured that they held a more senior political and military role within the southern region of Connacht. Over time, as the descendants of this Richard consolidated their leadership role over that territory, the name Clann Riocaird became equated with their line as distinct from the original Clann Riocaird and the territory over which they achieved dominance known as Clanricarde.

Of the original Clann Riocaird, the descendants of Hubert and John de Burgh were relegated to a subservient position, rendering services and dues to the senior-most descendants of Sir William liath’s son Richard, their family lands being confined to a smaller region within the territory of Clanricarde about Kilchreest and elsewhere. The descendants of Hubert came to be known as the MacHubert Burkes, while the senior-most descendants of Huberts brother John became known as MacRedmond Burke.

Hereinafter the term Clanricarde Burkes came to refer to the descendants of Sir William liath’s son Richard, among which family the chieftaincy of the territory of Clanricarde was confined.

Lionel, Duke of Clarence, Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht

Lionel Duke of Clarence was eventually sent to Ireland in 1361 as the King’s Lieutenant at the head of a large army to attempt to contain the situation and regain control on the ground. His term in Ireland lasted until 1366, but in 1363 his wife Elizabeth de Burgh died. Lionel’s period in office in Ireland make little impact upon his Ulster and Connacht estates and he was unable to dislodge the incumbent de Burghs or Burkes from Connacht, who were gradually becoming more assimilated into the Gaelic environment. Two years after Lionel’s departure he married a niece of the Visconti of Milan, but died later that same year, leaving only Philippa, his daughter by Elizabeth de Burgh, as his heiress. Through Philippa’s later marriage to the English magnate Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, the legal title to the Ulster and Connacht estates passed to the Mortimers. The death of Lionel and the eventual passing of the titles to an English absentee only occasioned to render the de Burghs more secure in their possession of their territories.

At the close of the century, in 1394 the King of England, Richard II sailed for Ireland, with an entourage that included the Mortimer Earl of March, to attempt to regain lost ground. The King received the submission, among others, of Ulick de Burgh or Burke, head of the southern or Clanricarde Burkes, Walter de Bermingham of Athenry and O Connor Don of Connacht, who were knighted by the King. Though reconciled to the Kings grace, the Burkes maintained only a nominal relationship with the Dublin government and continued to hold their lands in spite of English law.

Throughout the following century the history of the eastern region of what would later be known as County Galway would involve raid and counter-raid between the rival families, the O Maddens, O Kellys and Burkes and their various allies, with little reference to the diminished authority of the Crown or the owners under English law to much of the lands of Connacht.

Continued at ‘Fifteenth Century.’

[i] Walsh, T., History of the Irish hierarchy with the monasteries of each county, biographical notes of the Irish saints, etc., D. & J. Sadlier & Co., New York, 1854, p. 444. Corbellynegall or ‘Corbally of the foreigners’ appears to be a reference to Corballymore in the early modern parish of Abbeygormican. In the 1407 Episcopal Rentals of the Diocese of Clonfert this denomination is given as ‘Corballimore nangall’ and listed alongside a number of others about the parish of Abbeygormican. (Nicholls, K.W., The Episcopal Rentals of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, IMC, 1970, p. 138.) The townland of Corballybeg lies near Corballymore in that parish but this appears as early as 1407 as a separate and distinct townland and would appear to be that ‘Cluain Idolsy alias Corballibeg’ listed in the 1407 Rentals immediately before Corballimore nangall. Another Corballybeg and Corballymore were located in the parish of Doonanoughta.

[ii] Connolly, P., An Account of Military Expenditure in Leinster, 1308, Analecta Hibernica, No. 30, 1982, pp. 1, 3-5.

[iii] Annals of Inisfallen.

[iv] Phillips, J.R.S., Documents on the early stages of the Bruce Invasion of Ireland 1315-1316, Proceedings of the R.I.A., Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, Vol. 79, 1979, pp. 263-4. Account of John le Poer of Dunoyl, dated Dunoyl, 3 October 1315.

[v] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), p. 241.

[vi] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), p. 241.

[vii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 243-9.

[viii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 243-9.

[ix] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 243-9.

[x] Connolly, P., Irish Exchequer Payments 1270-1496, Dublin, IMC, p. 315.

[xi] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, p. 212.

[xii] Knox, H. T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No.4, 1902, p. 406.

[xiii] Knox, H. T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No.4, 1902, Part II, pp. 393-406. ‘Total of old value of this cantred, part of the manor of Loghry, £116 8s. 2d. Total of value now, £42 10s. 4d.’

[xiv] Holland, P., The Anglo-Norman landscape in County Galway; land- holdings, castles and settlements, J.G.A.H.S., Vo. 49, 1997, p.185. (Richard son of Gilbert de Valle sued the prior of Abbeygormican ‘for fifty-four acres of land with their appertenances in Fynoughta, of which Dermod O Feigher, the former abbot, had unjustly disseized his father’. The same Dermod O Feigher was said to be abbot of Abbeygormican about 1309, in which year ‘William son of William Hackett, sued the abbot for five acres of pasture and forty of turbery in Corbellynegall.’ T. Walsh, History of the Irish hierarchy with the monasteries of each county, biographical notes of the Irish saints, etc., D. & J. Sadlier & Co., New York, 1854, p. 444.)

[xv] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No.4, 1902, Part II, pp. 393-406.

[xvi] A grange appears to have been centred in the parish of Kilquain, that gave its name to a quarter of that name but it is unclear of this was created at a later date.

[xvii] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No.4, 1902, Part II, pp. 393-406.

[xviii] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No.4, 1902, Part II, pp. 393-406.

[xix] Holland, P., The Anglo-Norman landscape in County Galway; land- holdings, castles and settlements, J.G.A.H.S., Vo. 49, 1997, p.185.

[xx] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 32, No.4, 1902, Part II, pp. 393-406.

[xxi] Holland, P., The Anglo-Norman landscape in County Galway; land- holdings, castles and settlements, J.G.A.H.S., Vo. 49, 1997, p.184-5.

[xxii] Cal. Pat. Rolls. Ed. III. Vol. IV.

[xxiii] Lydon, J., The Lordship of Ireland in the Middle Ages, Four Courts Press, Dublin 2003, p.124