© Donal G. Burke 2014

In the early seventeenth century the lands of the principal landholding family of the name Callanan lay in the townland of Grange in the parish of Fahy in the heart of Síl Anmchadha, the territory over which the chieftain of the O Maddens held sway. One of the earliest references to this specific family is to that of one ‘Cormock O Callanan of Grawnge’, who received a pardon in 1586.[i]

While the O Maddens and many of the other leading families of that territory were known as the ‘Síol Anmchadha’ or ‘seed of Anmchadha’ and were a branch of the wider Uí Maine family group, the O Callanans were of a different kin group.

The name was associated at an earlier period with a district much further to the west in Connacht, near Lough Corrib, within the diocese of Annaghdown. In his ‘Great Book of Genealogies,’ the seventeenth century Irish scholar Dubhaltach MacFirbisigh gives the Uí Challannáin of Ceall Chathghaile or Ceall Chathail as the physicians of Muintir Mhurchadha or of the O Flaherty chieftains of the Muintir Mhurchada.[ii] As such, MacFirbisigh states, they belonged to the Uí Bhriúin Rátha, a branch of the extensive Uí Bhriúin kin-group whose principal branch provided the O Connor Kings of Connacht at one time. Another version of this account describes the ‘Uí Callanain’ as the ‘comharba’ of ‘Cill Cathail’ while the following line gives ‘Uí Cendudhain’ (O Canavan) as the physician to the O Flaherty chieftain.[iii]

The Clonfert antiquary Rev. P.K. Egan was also of the view that the O Callanans were the comharbas or ‘coarbs’ of Kilcahill.[iv] The comharba was either a cleric or laymen who administered certain church lands associated with early monastic foundations. As ‘comharba’ he was regarded as the ‘successor’ to the founder of the particular church with which the lands under his control were associated and the selection of comharba was often made from among a sept or family who came to be regarded as the hereditary guardians of those lands. O Flaherty’s description of the O Callanans as hereditary physicians is noteworthy, however, as members of the name which flourished in the O Madden territory of Sil Anmchadha in east Galway appear to have been such in at least the late medieval period or early modern period.

The wide Uí Bhriúin kin-group was reputed to descend from one Brian, son of one Eochaidh Muighmheadhóin. Early references give this Brian as having six sons and later genealogies give him as having twenty-four. It has been suggested that this increased figure was a result of various tribes unrelated to the Uí Bhriúin who came under the control of the Uí Bhriúin claiming or being given pedigrees connecting them genealogically with their over-kings. In MacFirbisigh’s pedigree the Uí Bhriúin Rátha are given as descended from Cairbre Airdcheann, seventeenth son of Brian son of Eochaidh Muighmheadhóin. The Uí Bhriúin Rátha and Seola, however, are among those whom scholars believe may have been tribes of a different descent but given later fictitious Uí Bhriúin origins.[v]

The Muintir Mhurchadha (ie. ‘the people of Murchadh’) were a branch of a tribe known as the Uí Bhriúin Seola, closely connected with the Uí Bhriúin Rátha.[vi] Within the land of the Uí Bhriúin Rátha to the east of Lough Corrib and north of Galway, they occupied a district between Tuam and the Lough Corrib.[vii] Within this area lies the modern townland of Kilcahill in the parish of Annaghdown, between the towns of Claregalway and Tuam in County Galway.[viii] This would appear to have been the ancestral lands of the O Callanans, or at least a principal branch of the name, in the early medieval period.

The chief family of the Muintir Murchadha were the O Flahertys.[ix] Upon the conquest of Connacht by the Anglo-Normans in the mid thirteenth century, the O Flahertys were pushed further west, to the opposite bank of Lough Corrib.[x] It would appear that the O Callanans maintained a presence thereafter in the general vicinity about Kilcahill, with one Cormock O Callenane of Kiltoroughe, gentleman, party to a mortgage agreement with Burkes of Leackaghbegg in the barony of Clare in County Galway about 1621.[xi] This Kiltoroughe is to the modern townland of Kiltroge, near the later town of Claregalway, wherein stood the castle of Kiltroge, in the parish of Lackagh, barony of Clare.[xii] The castle and lands of Kiltroge was in the ownership of the Blakes from the thirteenth century and was still in their possession at this time, which would suggest that this O Callanan was renting his lands there.[xiii]

O Callanan of Grange, parish of Fahy

The principal landholding branch of the name established much further to the east, in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, lay within the territory of the O Maddens. Among the earliest references to this specific family is the pardon granted by the Crown to one ‘Gillegery O Kellenan of the Grange’ in 1585, alongside various others, the majority of whom were associated with the territory of the O Maddens. (Also extended a pardon in that year were Melaghlin cantaghe Y Kallanan, kern and Melaghlin O Callenen mcConnoghor O Callenan, kern, but with no identifiable address.) In the following year one ‘Cormock O Callanan of Grawnge’ was among those who received a pardon.[xiv] The townland of Grange in the late sixteenth century was situated in the O Madden territory of Síl Anmchadha (later the barony of Longford) in the parish of Fahy. It lay in close proximity to the castle and lands of the head of the O Horans at Fahy and comprised one quarter of land. The quarter was divided into two half quarters, one known as Lisnegransye and the other Lisdonnell, with the latter appears on Petty’s mid seventeenth century map of the barony to the north of Lisnagrange. Both of these place-names were in use in the mid seventeenth century and appear to relate to two ringforts within Grange that are no longer recorded on maps.

It was not uncommon for the hereditary physician of a chieftain to reside in close proximity to the principal castle of the territory associated with the office of chieftain. Sir John Davies in his 1609 ‘Lawes of Irelande’ noted that the mensal lands of the Gaelic chieftain were inhabited by families who over successive generations provided services to the chieftain. Included by Davies among the list of learned service providers established upon those demesne lands was the chieftain’s physician. Given Grange’s proximity to the north of the O’Madden chieftian’s principal castle of Longford, it may explain the last O’Madden chieftain’s claim to the Callanan’s ancestral lands. (Fitzpatrick E., Ollamh, Biatach, Comharba: Lifeways of Gaelic learned families in medieval and early modern Ireland, Proceedings of the XIVth International Celtic Congress, Maynooth 2011, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 2015, pp. 165-189.) Although occupied by the Callanans, the O Madden chieftain claimed a right to the lands of Grange. Following the death in March of 1605 of Donal O Madden, chieftain and ‘Captain of his Nation’, an inquisition taken at Loughrea in September of 1606 into the extent of his property found that he was seised in fee of numerous lands in addition to the castle of Longford. Included among those lands was Grange, but the inquisition acknowledged that, although counted among the lands of Donal O Madden, Grange was at that time claimed and possessed by Rickard O Calloran (recte: Callanan). (National Archives of Ireland, Dublin, R.C. 9/14, Exchequer Calendar of Inquisitions, Co. Galway, Vol. 14.)

Riccard O Callenan of Maghere-Ineirla (modern townland of Magheranearla, parish of Tiranascragh) was among the many within the barony of Longford granted a pardon by the Crown in 1603, in the first year of the reign of King James I.[xv] Magheranearla lay adjacent to Grange and this would appear to be the same Richard later described as ‘of Grange.’ The only significant landholders of the name in the barony of Longford confirmed in possession of their lands by the Crown in 1618 were Richard O Cullinan (recte: O Callanan) and Hugh O Cullinan of Grange in Galway County, gentlemen, who jointly held the one quarter of Grange.[xvi]

The barony of Longford in the early Seventeenth Century (in yellow), formerly the O Madden territory of Síl Anmchadha, showing the Callanan lands at Grange in the parish of Fahy (in green) and modern villages and towns (in red).

Aeneas Callanan

Aeneas Callanan, who studied as a cleric to serve the infant Protestant Church in the diocese of Clonfert in the early years of the seventeenth century appears to have been one of this family of Síl Anmchadha. While still a student he was given a number of positions in the diocese, the income from which would have supported his studies. At the time of the 1615 Royal Visitation of the diocese, he was found to have held the vicarage of Kiltormer and ‘Lickeridge.’[xvii] The inspectors noted with concern, however, that he had by that time left his studies at Trinity College ‘nere Dublin’ and required the then Bishop, Roland Lynch, to account for the missing student. Lynch’s dedication to the Protestant cause was doubted by the visitators and he could only relate that Callanan had last been a student at Trinity College in April of the preceding year and had thereafter disappeared. He was unaware of his whereabouts.[xviii]

Callanan had remained faithful to the Catholic Church, however, and, given the persecution of that faith, it appears left the country to continue studies on the Continent as a Catholic. He appeared again in Ireland in 1624, causing some concern for the English administration of the province, who were fearful of foreign agents and priests secretly arriving from Rome or Spain fermenting discontent and rebellion within the country.

Sir Charles Coote, Lord President of Connacht wrote to the Lord Deputy Falkland about early May of 1624 to update him on recent information on Callanan and on various friars suspected of gathering support for a rising of the Roman Catholics in Ireland and in Scotland. The Lord Deputy had written to Coote of word he received of a Dominican friar and a ‘tall black man’ ‘out of Spain’ carrying letters on his person, whom the Lord Deputy took to be an O Madden. A spy was at that time with the friar, who informed them of the friars and his companion’s activities. While an O Madden, a soldier returned from the Low Countries, was then reported to be about the country and sought by the authorities, the man with the letters was identified by Coote as Aeneas Callanan.[xix]

Callanan was understood to be travelling incognito with his expenses paid by the King of Spain, but at that time Coote was unaware of what was contained within the letters. From information from his spy Coote could inform Falkland that Callanan landed in Munster, entered Connacht by way of Portumna and visited his father whom Coote described as having ‘lands very near the O Maddyn’s country.’ From there he made his way to the town of Galway ‘to meet with the chief father of that order (the Dominicans), that came over in company with him, one Doctor Lynch, a very learned man’ and brother of the Earl of Clanricarde’s land agent Sir Henry Lynch of Galway. Dr. Lynch travelled to Galway separately from Callanan, by way of Limerick.[xx]

Coote advised Falkland to maintain a careful watch upon the town and fort of Galway, believing it to be ‘a point for foreign invasion and there is a continual concourse of more priests there than in any town in all Ireland, whose assemblies of this kind are the certain forerunners of all rebellions in this country.’ His concern was magnified by what he regarded as reports of gatherings of priests ‘unusual both in the numbers and manner’ with one in particular in County Galway about early May of 1624 involving ‘the whole Popish clergy of the Archbishopric of Tuam. They meet’ he claimed, ‘not only themselves, but the principal gentlemen of the country attend them and their sons, who are merry lusty young men.’[xxi]

According to Coote’s source, Aeneas Callanan stated that two thousand men of the Irish regiment in the Low Counties were to be sent to Ireland ‘with spare arms to arm others that will adhere to them, but that they heard the narrow seas were straightly kept but if it be possible they may pass, they are appointed to land in Connaught near Galwaye.’[xxii] He undertook to pass on more information on Callanan within a short time but little further information survives of Callanan in the Irish records.

Early seventeenth century

The Meelick Chronicles record the death in 1631 of Richard Callanan, ‘a distinguished doctor.’[xxiii] He was buried at the nearby friary church at Meelick in East Galway ‘with his wife on the right side of the choir.’ In the late 1630s the Callanans of Grange were the only family of that name recorded as landed proprietors in County Galway, and the family lands were possessed by Richard Callanan’s son Florence, who held the half-quarter of land called Lisdonnell in Grange.[xxiv] Described at that time as ‘Florence Callanan Mc Richard’, he also held a parcel of land across the River Shannon in the townland of Ballymaccuolahan in the parish of Lusmagh. The half quarter of Lisnegransye was held at that time by the large landholder John Donnellan of Ballydonnellan.

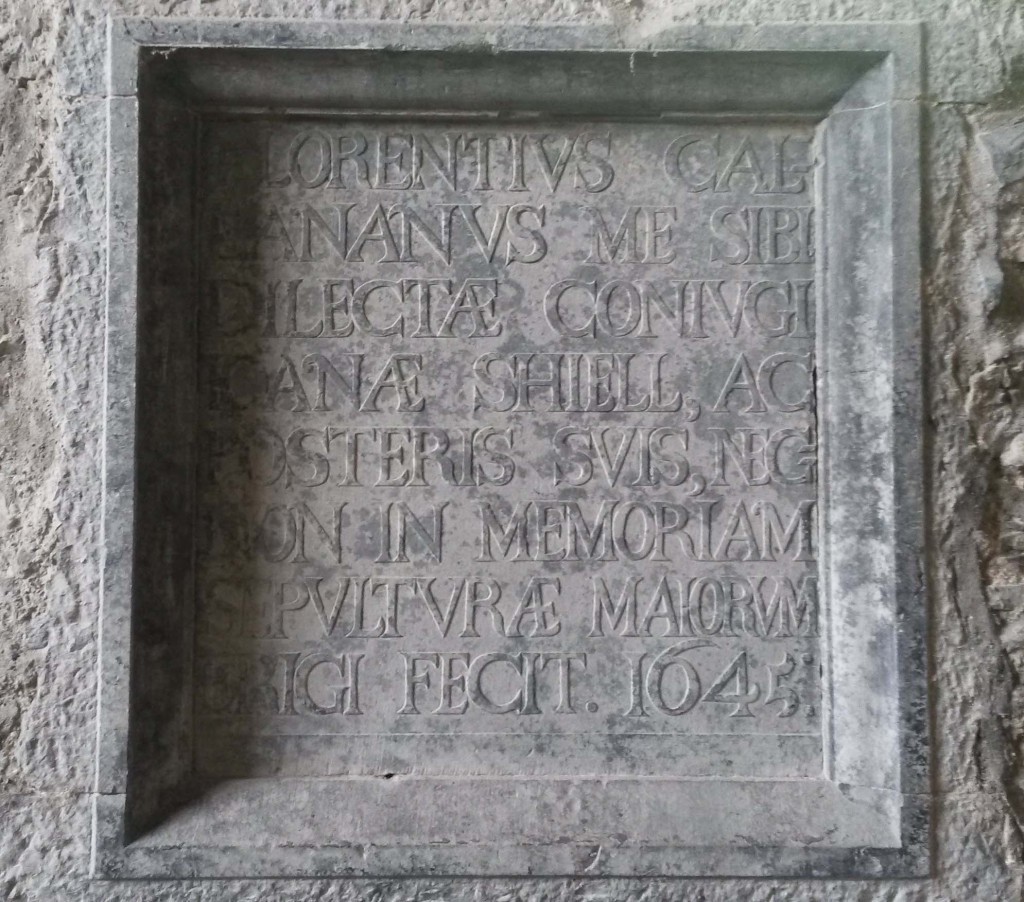

This would appear to be the same Florence Callanan of Grange, who, alongside such prominent local landholders as Ambrose O Madden of Brackloon, Coagh O Madden of Skycur (modern townland of Skecoor), Owen McDonell O Madden of Derryhiveny and William Tully of Cleaghmore, was one of the jurors in 1629 at the inquisition into the extent of lands and dues relating to the merchant Nicholas Blake of Ballymacroe, County Galway.[xxv] Florence Callanan, with his wife, was commemorated on a stone slab erected at Meelick friary church during the Rebellion of the 1640s; ‘Florentius Callananus me sibi Dilectae Conivgi Joanae Shiell, ac posteris suis, negnon in memoriam Sepulturae maioruim erigi fecit 1645.’

The seventeenth century Callanan memorial tablet, set in the south wall of the former Franciscan friary church at Meelick.

Members of the family were also buried at the nearby religious foundation at Clonfert. Richard Callanan, a late sixteenth century or early seventeenth century member of the family, appears also to have been a physician, his headstone, later affixed to the north wall of the nave of Clonfert cathedral read ‘Hic Iacet Dns. Ioes (O Donovans Ordnance Survey Letters give this as ‘Johannes’) et Ricard Callanan, Phici qui hunc tumultu fieri fecerut et ioes obiit 13 Mar 1612. IHS Maria.’

The 1612 Callanan gravestone, affixed to the interior of the north wall of the nave of Clonfert Cathedral.

Meelick friary

The Callanans were closely connected to the Franciscan friary at Meelick and provided members to that community, with one such, V. Rev. Fr. Bro. Eugene Callanan, serving as guardian of Meelick in 1669, 1670 and 1671 at least. The leading members also continued their assistance to the friars in other way. The friary was in need of reconstruction in the late seventeenth century and relied to a degree on the assistance, financial and otherwise, of the surrounding Roman Catholic landed families. Florence Callanan appears to have taken an active part in its support at this time. William Yelverton approved a builder in January of 1685 for rebuilding works to the friary and in February an agreement was drawn up between Cornelius and Edmund Londregan on the one part and Florence Callanan, whereby the Londregans agreed ‘ to give and to deliver unto the said Florence as much fitted timber as will roofe the Abby of Meelick.’

Cromwellian period

The Callanans lost possession of their lands in this area as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century. Florence Callanan of Grange had his lands confiscated and in June of 1656 was allocated 234 profitable Irish acres in the parish of Kiltormer and a similar figure in the parish of Duniry.[xxvi]

Following the turmoil of that period and the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, an Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time. Under the Act of Settlement Nicholas Callanan was confirmed in possession of lands in Kiltormer and Abbeygormacan. Under the Act his Kiltormer estate comprised of 44 profitable acres in Teagh, 102 profitable acres in Drumnegleine and 64 acres in Skycur, the latter two parcels held before the Cromwellian confiscations by Cohagh McLaughlin O Madden. Callanan’s Abbeygormacan lands under the Settlement consisted of only four profitable acres in Lorga.

The Callanan’s former lands at Grange in Fahy was settled upon Jane Coote, Countess Mountrath, as one of a number of parcels she was granted throughout County Galway.[xxvii] From this time until the early twentieth century, the Callanans would be seated in the parish of Kiltormer.

Jacobite-Williamite War

When the Roman Catholic King James II was deposed and the crown offered to his Dutch son-in-law, the Protestant Prince William of Orange and his wife Mary, the Irish Catholics rose up in support of King James, and an army was sent by the French King to reinforce James’ Irish supporters, the Jacobites. In March 1689 James landed in Ireland to head his army here, hoping to regain his throne through Ireland. For their part many of the Irish Catholics hoped to recover much of their former lands that they were denied under the settlements after Charles II had been restored.

At the outbreak of war in Ireland between the Jacobites and the Williamite supporters of William and Mary, many of the most prominent Roman Catholic landholders of county Galway had taken up commissions as officers in the newly formed Irish Jacobite regiments. Four regiments raised from county Galway saw active service throughout the war but the senior-most members of the Callanans appear to have served as officers in a Kings County regiment, with Captain Alexander Callanan, Lieutenants Florence and John Callanan and Ensign Michael Callanan, all serving in the regiment of Colonel Sir Heward Oxburgh.

Following the Jacobite defeat at the hands of the Williamite army of William of Orange, Captain Florence Callanan of Dromglew, County Galway, was among who sought to avail of the articles of the Treaty of Limerick about 1698.[xxviii] This ‘Dromglew’ appears to be the townland identified in the late 1630s as the quarter of Drumnegleine, in the parish of Kiltormer, wherein Nicholas Callanan had been confirmed property under the Act of Settlement. While a large number of Jacobites sailed for France in the immediate aftermath of the war, Florence Callanan remained in Ireland and the Meelick friars recorded the his death in their obituary book thus ‘this 23rd May, 1744 died fortified by the sacraments of the Church, Florence Callanan, spiritual father of this convent, and a cavalry officer of King James II. May he rest in peace.’

Conversions to Protestantism

Skycur in the parish of Kiltormer, (the modern townland of Skecoor) part of the lands confirmed on the family under the Act of Settlement, was the seat of the Callanans by the early eighteenth century. In 1741 the will of Nicholas Callanan of ‘Sciaghcor, Galway’, was proved and in that same year Dominick Callanan of Skycur converted to Protestantism.[xxix] This Dominick would appear to have been among the senior-most of the name in the late eighteenth century as Dominick Callanan ‘of Skeacor,’ gentleman, in a deed dated 14th January 1783 granted a thirty-one year lease commencing on the 1st November of the previous year of the townland of Skeacor to Mathew Connolly of Clonlahan, County Galway, gentleman, ‘for and during the natural life and lives of Mathew Connolly, his brother John Connolly and Mark Lynch of Ballinasloe, Esquire’ for a yearly rent of £20 sterling.[xxx]

In 1775 Peter Callanan of Skycur, gentleman, also converted.[xxxi] This would appear to be the same Peter Callanan whom the friars of Meelick recorded as having died in 1795 as Peter Callanan of Skeacur, Co. Galway was given as deceased at the marriage in April 1812 of his third daughter Honora to James Madden of Summerhill.[xxxii] Brief notes taken by Betham from this Peter’s will describe him at his death as ‘of Cottage, Co. Galway’. His will, dated 11th March 1795 and proved on 5th September of the same year related to the Skycur estate and gave his wife as Honora and his brothers as Joseph and John Callanan. The same document gave his eldest son as Florence and his second as Daniel and his daughters as Helen, Catherine, Honora, Mary, Anne and Frances.

Various nineteenth century members of the family

The Gaelic poet O Raftery composed a poem commemorating a duel which took place during his lifetime involving a Donelan of Ballyeighter and Callanan of Eyrecourt, both of whom were on cordial terms until a dispute arose at a ball or dinner given in Callanan’s residence, in which Donelan took offence at a remark made by Callanan with regard to his behaviour. One later account of the ensuing duel fought between both men gave the duelling ground as located in the townland of Ballydonagh, between Kiltormer and Lawrencetown. One Joseph Hamilton, writing in 1829, recorded that ‘in a duel at Eyrecourt, Mr. Donnellan killed Mr. Callanan, who was his bosom friend and school-fellow. The quarrel was about a neck handkerchief, which the latter lent to the former when absent from home.’[xxxiii] Contemporary newspaper accounts of the encounter give the duelling ground as in Belview, near Ballydonagh and gave the duellists as Edward Callanan of Eyrecourt and Patrick Donelan of Ballyeighter, Esq. The duel was fought on a Saturday in mid October of 1821, with one report asserting that on the first discharge of pistols Callanan was killed instantaneously when Donelan’s ball entered his heart. Another contemporary account asserted that three shots were fired, with Callanan hit on the first shot and mortally wounded by the second. The subsequent inquest returned a verdict of wilful murder against Patrick Donelan.[xxxiv]

Celia, daughter of John Callanan, Esq. of Eyrecourt, Co. Galway married in 1824 Peter Nugent-Fitzgerald, Esq. of Soho House, Co. Westmeath.[xxxv]

John Callanan, Esq. ‘of Tullywood Cottage, near Eyrecourt’ married Eleanor, eldest daughter of the Rev. Dr. Eyre of Eyrecourt, ‘second cousin to the Earl of Arran and grand-niece of the late Lord Eyre’ in 1820.[xxxvi] A branch of Callanan family appears to have settled in Dublin by about the late eighteenth century, with this John of Tullywood Cottage providing an affidavit for Florence, third son of Joseph Callanan of Dublin, wine merchant, by his wife Ellen Fitzgerald to facilitate his entry as a student at Kings Inns. Both of the parents of Florence were deceased when Florence was admitted as a student at Kings Inns in 1821.[xxxvii]

John Calanan, Esq. of Tully and Mrs. Calanan were listed in Pigot’s Directory among the ‘nobility, gentry and clergy’ about Eyrecourt in 1824 while ‘Peter Callanan of Skecur, Eyrecourt, esquire,’ was among the subscribers to Samuel Lewis’s 1837 Topographical Dictionary of Ireland.

One Nicholas Callanan practised as an attorney with an address at Main Street, Eyrecourt in 1846.[xxxviii] He would appear to have been the fifth son of John Callanan of Eyrecourt by his wife Celia O Brien. He was educated at Eyrecourt and thereafter, with an affidavit provided by Florence Callanan, was admitted as a student at Kings Inns in 1824.[xxxix]

Ancoretta Eyre, third daughter of Thomas Stratford Eyre of Eyreville by his wife Grace Lynar Fawcett, married William T. Callanan of Skycur. This Ancoretta Callanan alias Eyre died in 1870.[xl]

Newpark, the name given to the Callanan residence in Skycur, was seat to Peter Callanan about 1855, where he held the townland in its entirety at the time of Sir Richard Griffith’s Valuation of Ireland. He appears to have died before 1858 as he was described as deceased when his youngest daughter, Jane, wife of William Burns, Esq., died at Sandymount Strand in Dublin on 7th May 1858.[xli]

The same Peter Callanan of Skycur appears to have been the father of two young members of the Callanans of Skycur who became embroiled in a homicide case in 1861. The incident occurred on the evening of the eleventh of December of that year, when both Peter and James Callanan were travelling in a car with James Lynch of Garrison and their driver, one Martin Curley and overtook two men at the gate leading to the house of a man named Killeen at Derrywillan, on the outskirts of Tynagh village. Both men, James Hearne of Cloncona and his twenty-one year old brother-in-law Thomas Sheil of Marble Hill, were returning from the fair at Tynagh and, as the car came upon them, one of the men in the car asked of Hearne the identity of the individual who lived at Derrywillan. Lynch, ‘described as ‘of excitable temperament,’ took offence at what he regarded as an insulting response and leaped from the car, followed by the young Callanans ‘and proceeded to inflict punishment for what they considered insolence.’ Sheil rushed to the defence of Hearne and in the ensuing scuffle, suffered a blow to the head with the knotted end of a horse-whip which fractured his skull and left him prostrate on the ground for a time. All the parties eventually went their separate ways and little notice was taken of Sheil’s injury over the following days until he was visited by Dr. Morgan of Eyrecourt. Sheil’s condition was such that the authorities ordered the constabulary from Eyrecourt to proceed to Skycur where James Callanan was arrested and Peter Callanan later surrendered himself to the police. For his part Lynch of Garrison evaded the constabulary initially. Sheil, however, died at five o’clock on the following Monday.[xlii]

The inquest taken on the day after Sheil’s death found his death to have occurred as a result of the blow he received on 11th December and ‘the said blow was given by either James Lynch, Peter or James Callanan, there being no evidence to show by which of the three given, but each aiding and assisting the other.’ James Callanan was committed for trial at the next Galway assizes and Martin Curley, their driver, was called to give evidence. The contemporary newspapers described the deceased as the only son of a widow in comfortable circumstances, of sober and inoffensive habits, but Hearne, on the contrary, was considered ‘to be rather offensive.’ The same newspapers described all three accused as ‘persons in a respectable condition’ and reported that ‘for the Messrs. Callanan the greatest sympathy (is) felt throughout the district. Both young gentlemen have ever been characterized by kindness and amiability of disposition and their disagreeable position at present is, therefore, the more acutely felt by their relatives.’[xliii]

Lynch was eventually apprehended and all three accused were convicted for the manslaughter of Sheil. The judge in the case, Chief Justice Monaghan, sentenced James Lynch and Peter Callanan to twelve months imprisonment with hard labour. James Callanan, owing to his youth, was sentenced to nine months imprisonment and the latter was also required to pay a fine of £30 as compensation for injury done. All were required to find bail to keep the peace for following seven years.

In July of 1879 ‘The Loughrea Illustrated News’ carried the obituary of Peter Callanan P.L.G., who died of consumption at Skycur at the age of twenty-nine years in June of that year. He was described therein as ‘the youngest son of the late Peter Callanan, Esq.’[xliv] In the middle of the 1870s Matilda Callanan was owner of an estate of almost four hundred acres in County Galway while James Callanan of Skycur was listed as among the executors of the 1879 will of one John Brennan who farmed in the townland of Lissreaghan, near Lawrencetown.

Last of the Callanans at Skycur

The family maintained their unbroken line at Skycur from their transplantation in the seventeenth century until the early twentieth century. Despite the conversions to Protestantism of some of the senior members of the family in the eighteenth century, the last of the family at Newpark appear to have been unmarried sisters, Rose and Mary Callanan, both Roman Catholic, the daughters of Peter Callanan. In 1901 Rose, the elder, aged fifty two, was given as head of the family and her sister Mary forty-seven. Both described themselves as landowners. Mary, the younger of the two, died after a long illness at Skycur on 24th January 1903.[xlv] In 1911 Rose was the sole Callanan present at Newpark, although she gave her age as seventy years. The lands thereafter passed out of the hands of the Callanans.

[i] Fiants Eliz. I

[ii] Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp. 448-451. No. 204.8.

[iii] O Flaherty, R., Ogygia: or, A chronological account of Irish events: collected from very ancient documents, (translated by Rev. James Hely), Vol. II, Dublin, W. M’Kenzie, 1793, Part III, Chapter LXVI, p. 369. The historical fragment from which the latter reference to O Callanan as comharba at Kilcahill was said to have been preserved in an ancient vellum manuscript in the library of Trinity College Dublin, H. 2. 27, p. 188.

[iv] Egan, P.K. and Costello, M.A., Obligationes pro Annatis Diocesis Clonfertensis, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 21, 1958, p. 53, footnote no. 3.

[v] Knox, H.T., The Early Tribes of Connaught: Part I, J.R.S.A.I., Vol. 10, no. 4, 1900, p. 350.

[vi] Walsh, P., Connacht in the Book of Rights, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. XIX, nos. i & ii, 1940, pp.13-14.

[vii] Knox, H.T., The History of the County of Mayo to the close of the sixteenth century, Dublin, Hodges, Figgis & Co., Ltd., 1908, between pp. 100 and 101, Map entitled ‘the de Burgo Lordship of Connaught.’

[viii] The ruins of the small church of St. Cathaldus (ie. ‘St. Cathal’) from whom Kilchaill evidently derives its name, lies on the roadside in the adjacent townland of Corrandrum, while near the small church lay an archaeological monument known as ‘leacht Chill Chathail’ or ‘the stone slab of St. Cathal.’

[ix] Walsh, P., Connacht in the Book of Rights, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. XIX, nos. i & ii, 1940, pp.13-14; Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp. 448-451. No. 204.8.

[x] Walsh, P., Connacht in the Book of Rights, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. XIX, nos. i & ii, 1940, p. 11.

[xi] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, pp. 21, 93.

[xii] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, p. 93. This castle was in the possession of one Colonel Thomas Sadler in the 1660s and claimed by one John Blake in the late seventeenth century as ‘formerly in the actual possession of the claimant by descent from his father and ancestors.

[xiii] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, pp. 93-7.

[xiv] The Irish Fiants of the Tudor Sovereigns during the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Philip and Mary and Elizabeth I, Vol. 2, 1558-1586, Dublin, Edmund Burke Publisher, 1994, pp. 676-7 (no. 4675), pp. 680-1 (no. 4689).

[xv] Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland, 1800, I James I, Part I, pp. 18-20.

[xvi] Pat. 16 James I, p. 416.

[xvii] Egan, P.K., The Royal Visitation of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, 1615, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. XXXV, (1976), pp. 67-76.

[xviii] Egan, P.K., The Royal Visitation of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, 1615, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. XXXV, (1976), pp. 67-76.

[xix] Russell, C.W. and Prendergast, J.P. (ed.), Calendar of the State Papers of Ireland of the reign of James I, 1615-1625, London, Longman & Co., 1880, pp. 495-7.

[xx] Russell, C.W. and Prendergast, J.P. (ed.), Calendar of the State Papers of Ireland of the reign of James I, 1615-1625, London, Longman & Co., 1880, pp. 495-7.

[xxi] Russell, C.W. and Prendergast, J.P. (ed.), Calendar of the State Papers of Ireland of the reign of James I, 1615-1625, London, Longman & Co., 1880, pp. 495-7.

[xxii] Russell, C.W. and Prendergast, J.P. (ed.), Calendar of the State Papers of Ireland of the reign of James I, 1615-1625, London, Longman & Co., 1880, pp. 495-7.

[xxiii] N.L.I. Dublin, MS 5203, Copy of records of the Franciscan Convent of Meelick, Co. Galway, made by Fr. James Hynes in 1858. ‘2, March 1631, Obiit Richardus Callanan Insignis medicus stirpis Wadingorum sepultus est cum sua uxor a dextra parti chori.’

[xxiv] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. 180. He is described therein as ‘Florence Callanan Mc Richard’.

[xxv] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, pp. 36-7.

[xxvi] Simington, R.C., The Transplantation to Connacht 1654-58, Shannon, Irish University Press, for the I.M.C., 1970, p. 148, 157; Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Marquess of Ormonde K.P., Presented at Kilkenny Castle, Vols. I, II, III, Historical Manuscripts Commissions, Fourteenth Report, Appendix, Part VII, London, Eyre and Spottiswode for Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1895, p. 128. ‘List of Transplanted Irish 1655-1659, No. 1, ‘An account of lands set out to the Transplanted Irish in Connaught.’

[xxvii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962.

[xxviii] Analecta Hibernica No. 22, I.M.C., 1960, p. 109

[xxix] Index to Clonfert Wills 1663-1857, Supplement to the Irish Ancestor Vol. II, no. 2, 1970; Byrne, E. and Chamney, A. (ed.), The Convert Rolls, the Calendar of the Convert Rolls, 1703-1838 with Fr. Wallace Clare’s annotated list of converts, 1703-78, Dublin, IMC, 2005, pp. 35-6.

[xxx] Registry of Deeds, Dublin, Lib. 347, p. 543.

[xxxi] Byrne, E. and Chamney, A. (ed.), The Convert Rolls, the Calendar of the Convert Rolls, 1703-1838 with Fr. Wallace Clare’s annotated list of converts, 1703-78, Dublin, IMC, 2005, pp. 35-6.

[xxxii] Index to the marriages in Walkers Hibernian magazine 1771-1812 by Henry Farrar; London, 1890, p. 191. The Meelick friars in recording his death made no reference to Peter Callanan having been buried in their church.

[xxxiii] Hamilton, J., The only approved guide through all the stages of a quarrel, London, Hatchard & sons; Betham & Co., Liverpool & Millikin, Dublin, 1829, p. 96.

[xxxiv] Dublin Weekly Register, 20 October 1821; Saunders News-Letter, 22 October 1821, The Belfast Commercial Chronicle, Mon. 22 October 1821, p.1.

[xxxv] Burke, B., A genealogical and heraldic dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland for 1853, Vol. III, London, H. Colburn, (Addenda), p.361.

[xxxvi] The New Monthly Magazine and Universal Register, 1820, London, H. Colburn & Co., Part I, (January to June), p. 760.

[xxxvii] Keane, E. And Beryl Phair, P., Kings Inns Admission Papers 1607-1867, Sadlier, T.U. (ed.), Dublin, Stationary Office for I.M.C., 1982, p. 72. The entry relating to Florence erroneously gives the address of John Callanan as ‘Sullywood Cottage, Co. Galway.’

[xxxviii] Slaters Directory 1846

[xxxix] Keane, E. And Beryl Phair, P., Kings Inns Admission Papers 1607-1867, Sadlier, T.U. (ed.), Dublin, Stationary Office for I.M.C., 1982, p. 72.

[xl] Hartigan, A.S., A short account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway.

[xli] Saunders News-Letter, 8 May 1858, p. 3.

[xlii] Dublin Evening Mail, 24 December 1861, p. 4; Kings County Chronicle, 26 March 1862, p. 5.

[xliii] Dublin Evening Mail, 24 December 1861, p. 4; Kings County Chronicle, 26 March 1862, p. 5.

[xliv] The Loughrea Illustrated News, 1 July 1879.

[xlv] Leinster Reporter, 24 January 1903, p2.