© Donal G. Burke 2015

Kiltormer in the early twentieth-first century is a parish and village in the barony of Longford in the east of County Galway, in what was in the late medieval period Síl Anmchadha, the ancestral territory of the O Maddens. Samuel Lewis in his 1837 ‘Topographical Dictionary of Ireland’ gave the name of the parish as Kiltormer and the village therein as Kiltormer-Kelly. While much of the land about the parish of Kiltormer in the mid nineteenth century formed part of the estate of the Cromwellian Eyre family resident at Eyreville, Lewis described the village of Kiltormer-Kelly as located on the estate of Charles Kelly, ‘a friar, whose ancestors founded Kilconnell Abbey and some others in this country.’[i] The friar and Kelly family to whom Lewis made reference resided in the mid nineteenth century at Bettyville, in the nearby townland of Cloonlahan (Eyre) in the adjacent parish of Killoran.[ii]

Lewis described Kiltormer-Kelly as ‘a rising village, in a well-cultivated district, within five miles of the Grand Canal and has cattle fairs on the 17th of February, May, August and November.’ He noted that ‘a fine quarry of black marble’ had recently been discovered in the vicinity.

According to the Registry of Clonmacnoise, a quarter of land in Kiltormer was one of the seventeen townlands and three dúnta or strong fortified places that Cairbre crom, ancient chieftain of the territory of Uí Maine or Hy Many, reputedly bestowed upon the Abbey of St. Ciaran of Clonmacnoise.[iii] Cairbre crom was regarded in the Gaelic manuscripts and pedigrees as the sixth century ancestor of the O Kellys, Maddens, Egans, Kennys, Treacys, Larkins and many of the families of east Galway and south Roscommon and while the Registry significantly post-dates the alleged bestowal by him of the site at Kiltormer, it would suggest that a site within the parish of Kiltormer was regarded as having an ecclesiastical use from a very early period.

By at least the late medieval period a parish church, in all likelihood similar to those surviving examples at Kilmalinogue or Kilclooney in east Galway, had been constructed at Kiltormer. In the late fifteenth century Phillip ‘odownylay’ (ie. O Donnelly or O Donnellan), priest of the diocese of Clonfert was assigned the perpetual vicarage of the parish church of ‘Kiltormoyr.’ About late 1487 or early 1488 he presented a petition to the Papal authorities in which he referred to his having repaired and restored ‘at great expense’ the church at Kiltormer, which had prior to that time lain in ruin.[iv]

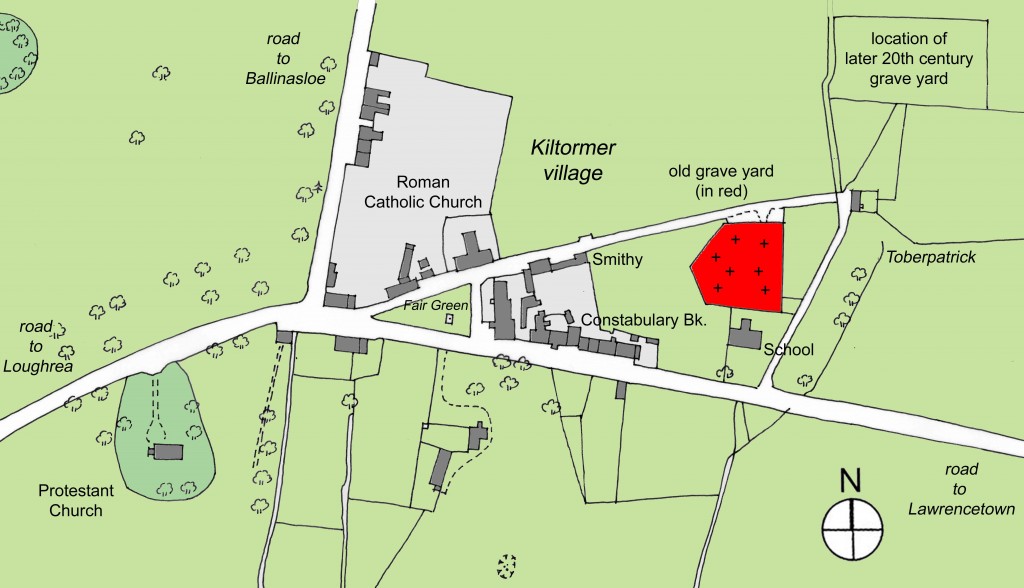

The church Odownylay claimed to have repaired is likely to have been located at the old graveyard in the townland of Kiltormer West in the middle of the later village. In a letter dated November 1838 Patrick O Keefe, in describing the antiquities of the parish, referred to the ‘old grave-yard still in use’ and the Protestant church of the parish as having once stood in that graveyard, in which church service was performed until a few years prior to O Keefe’s arrival.[v] That church he described as having been ‘thrown down’ or demolished not long before 1838, with only the foundation visible to O Keefe. (St. Thomas’s Church, a new Protestant church, was constructed at Kiltormer about 1815 on a site given by Thomas Stratford Eyre.)[vi] It would appear that this demolished church was the earlier medieval church of the parish and, like Kilreekill and certain other churches, may have been adapted for later Protestant use. (Kilreekill, originally a Roman Catholic church, served as a place of worship for a nascent Protestant community in the 1630s.)[vii] No trace of its foundation was apparent in the graveyard by the late twentieth century.

Map by the author showing the location of the old graveyard (in red) in the late nineteenth century village of Kiltormer, with the Roman Catholic church located at the Fair Green, the early nineteenth century St. Thomas’s Protestant church to the west of the village proper and Toberpatrick in a field to the east of the old graveyard.

The location of the Kiltormer church in use in the late medieval period in the modern townland of Kiltormer West is confirmed by O Keefe’s description of the old Kiltormer graveyard being located near a holy well called Tobar Pádruig (ie. ‘the well of Patrick or St. Patrick.’), in the townland of Newtown-Eyre ‘at which a pattern or station was held on the first Sunday of August.’[viii] While Toberpatrick is located in close proximity to, and to the east of, the old Kiltormer graveyard it occurs in the modern townland of Kiltormer East and not in the townland of Newtowneyre. No well of that name was shown on the mid nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps in that townland but a well of that name was shown on the same maps in Kiltormer East, where it is still visible into the twenty-first century. No ruins of a church was indicated within the boundary of the old graveyard on the same maps, which indicated the location of the more recent Protestant church in the townland of Newtowneyre, to the west of the village proper.

For a selection of graveyard inscriptions refer to ‘Old graveyard burials.’

[i] Lewis, S., A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, London, S. Lewis & Co. , 1837.

[ii] Charles Kelly, ‘Dominican Fryar’ and Malachy Kelly, both with an address of ‘Bettyville, Aughrim,’ were among five Catholic clergymen, one Protestant clergyman and five ‘lay gentlemen’ who appended their names to an appeal for clemency to the Lord Lieutenant and Governor General of Ireland in April 1836, requesting the commutation of the sentence imposed on the sixteen year old Edward Killilea and the fifteen year old Daniel McKeigue from Transportation for Life to Imprisonment. Both men had been found guilty of manslaughter. (The one Protestant clergyman who appealed for clemency was ‘M. Groome, Rector, Kiltormer Glebe.’) Malachy Kelly, when writing to Ambrose Madden of 112 Talbot Place, Dublin in January 1843, gave his address as ‘Bettyville, Kiltormer’ and informed Madden that ‘Fr. Charles’ had died but that the rest of the family were well. (RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 25-0-39/JOD/168).

[iii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 15.

[iv] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 14: 1484-1492, London, (1960) Vatican Regesta 732: 1488, pp. 220-223.

[v] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, p. 113. Letter dated Loughrea, 6 November 1838.

[vi] Lewis, S., A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, London, S. Lewis & Co. , 1837.

[vii] B. MacCuarta, S.J. (ed.), A presentment of Recusants, East Galway, 1632’, JGAHS, Vol. LXI, 2009, pp. 74-78.

[viii] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, p. 113. Letter dated Loughrea, 6 November 1838.