© Donal G. Burke 2014

The Wall family are of Anglo-Norman descent, their family name appearing in the Latin documentation of the medieval period as de Valle. The lands of the principal Connacht branch of the wider family in the late medieval and early modern period lay to the northeast of the town of Loughrea, in the parish of Kilreekill and included parts of the adjacent parish of Abbeygormacan to its east. Like the Burkes and the nearby Dolphins, the family had gradually become gaelicized by the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

A pedigree registered in 1716 by Hawkins Ulster King of Arms gives several principal Wall families of Ireland as descended from one William Du Vall or Wall, who accompanied Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke to Ireland in 1172 and who died in 1210.[i] This source gives John Du Vall alias Wall of Johnstown, County Carlow, the son of this William Wall as having had four sons who each founded prominent families; William of Johnstown, ancestor of the Walls of Johnstown, County Carlow and of Kilcash and Rathkien, County Tipperary; Walter of Droughty, County Galway, the second son, ancestor of the Walls of Coolnamuck, County Waterford; Richard, ancestor of the Walls of Dunmoylan, County Limerick and John, the fourth son, ancestor of the Walls of Ballymalty.

Hawkins Ulster was not noted for the accuracy of his genealogical pedigrees and two conflicting pedigrees survive from the same Ulster King of Arms relating to this same wall descent. While the former is dated 1716, another earlier pedigree appears in G.O. Ms. 159 (Genealogical Office manuscript) and gives the four brothers as the sons of the first William Du Vall alias Wall, knight and made no reference to a John as father of the four brothers. Both pedigrees give Walter, the second eldest of the four brothers, as ‘of Droughty, County Galway.’ The earlier pedigree, however, gives Walter and the nine consecutive lineal descendants of Walter, as all seated at Droughty. Noticeably, none of their spouses, however, are from Connacht and derive from such places as Counties Waterford, Tipperary, Kilkenny and Carlow. The 1716 pedigree likewise gives the same spouses from the same locations but only gives the original Walter as ‘of Droughty, County Galway’ and gives the succeeding ten generations as ‘of Coolnemucky, County Waterford.’

At the introduction to the 1716 pedigree Hawkins attributed the removal of the Walls from Droughty to a dispute that arose during the lifetime of Richard de Burgh, the Red Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht, involving the original Walter Wall of Droughty which resulted in Wall quitting the lands of the Red Earl and settling at Coolnemucky or Coolnamuck within the lands of the Butler Earl of Ormonde, wherein his descendants remained seated thereafter. While members of the Wall family did come to be seated at Coolnamuck, Hawkins pedigree made no mention of the fact that members of the Wall family remained in possession of lands about Droughty or Drought in the parish of Kilreekill within the lands of the de Burgh Earls of Ulster into the early modern period.

With regard to the family later found in east Galway, persons of the name occur in east Connacht from the thirteenth century. Sir Walter de Valle and Gilbert de Valle appeared alongside other Anglo-Normans with landed interests in Connacht, such as William Croc and William Haket, as witnesses to a number of legal transactions involving the transfer of lands about the manor of Aughrim, in the cantred of Omany in east Connacht between Theobald Butler, Sir Richard de Rupella and others about 1270.[ii]

Gilbert de Valle held lands connected with Abbeygormacan by about the end of the thirteenth century or the beginning of the fourteenth century on the borders of what was formerly the territory of the O Maddens. Richard son of Gilbert de Valle sued the prior of Abbeygormacan in what would later be east Galway ‘for fifty-four acres of land with their appurtenances in Fynoughta, of which Dermod O Feigher, the former abbot, had unjustly disseized his father’. (This Fynoughta may be a reference to the nearby Finnure or the quarter of Fynagh in the early modern parish of Clonfert.) This Richard de Valle appears to have flourished about the early years of the fourteenth century as the same Dermod O Feigher was said to be abbot of Abbeygormacan about 1309, in which year ‘William son of William Hackett sued the abbot for five acres of pasture and forty of turbery in Corbellynegall.’[iii]

As Walter de Valle was described as a knight about 1270, he would appear to have been a senior figure within the family based in Connacht, as the taking of knighthood in the medieval period was an expensive undertaking involving significant obligations on the part of the knight to his overlord. One Walter de Valle was one of six knights of the lordship of Connacht and eight others who served as jurors in an inquisition taken at Castledermot in 1305.[iv]

Another of this wider family, Adam de Valle, held of the King, in capite, in Connacht ‘three villatas of land in the march near the Irish at the Cammys, Mornolk, Hynchecoulcass and Molaghnumches.’[v] He died about 1307 and an inquisition taken in that year stated that his heir was Stephen de Valle and aged at least twenty-one years. Because of the unsettled nature of Connacht at the time ‘in these days of war’, Stephen sought to dispense with the proving of his being of age and to have direct seisin of the lands, on the basis that to leave the area would be dangerous. Given that the three villatas were claimed by his son to have composed Adam de Valle’s entire estate in Ireland, it would appear unlikely that this Adam was the same man as one Adam de Wal, found holding lands at Balychery in the Manor of Ardrahan in 1289.[vi]

A number of the Anglo-Norman Crok family and their allies, led by Sir John Crok, were charged and committed to prison or fined for their parts in raids on Connacht lands about 1305.[vii] The depredations in Connacht appear to have involved damage to the lands there of Geoffrey de Valle, for which one John de Burgh was detained in prison in Dublin about 1305 on charges of felony, arson, robbery and other crimes ‘committed in the company of John Crok, knight.’[viii]

In what may have been a related case, Sarra, widow of Philip Crok and Mabilla, widow of Eustace Crok made a legal appeal in what was then the county of Connacht against Walter de Valle, it would appear attributing responsibility to him for the death of their husbands. Walter, who ‘rendered himself to the King’s prison’, disputed the nature of the accusations. Both women were commanded to appear before John Wogan, the Justiciar in Ireland, in April of 1306 in relation to the case, but on the appointed day the Sheriff reported that neither could be located. Both were then required to appear ‘at the house of Robert Haket and Nicholas Crok, their pledges to prosecute.’[ix]

The Geoffrey de Valle whose Connacht lands were raided by the Croks was in all likelihood the same Geoffrey de Valle who in 1308, along with such prominent Anglo-Normans and Gaelic Irish of Connacht as Thomas Dolfyn, Philip Haket, Richard le Blake, Rory O Connor, Tadhg O Kelly and John or Eoghan O Madden, attended with men at arms upon the Deputy Justiciar Sir William liath de Burgh on a military expedition on the king’s behalf against the Irish of Leinster.[x]

While the location of the lands of Geoffrey de la Valle raided was not given, he did hold lands in ‘Leswagh’ (modern parish of Lusmagh) in the cantred of Síl Anmchadha, the ancestral lands of the O Maddens, at the time of the 1333 Inquisition Post Mortem of the Lordship of Connacht following the murder that year of the young de Burgh Earl of Ulster by conspirators both within and without his own wider family group.[xi]

Decline of the Anglo-Norman colony

With the sudden loss of the Earl without a male heir at a time when the Anglo-Norman colony was in decline and infighting among the leading members of the family, the principal lordship in Ireland began to crumble. In Ulster, the powerful O Neills, along with the Maguires and O Cahans broke free of the Crown, and in the turmoil that followed in Connacht, the native Irish such as the O Kellys and O Maddens, began to expand and regain lost ground.

The Wall family, in the upheaval following the Gaelic resurgence in the fourteenth century, maintained a presence within the gaelicised territory ruled by the descendants of the de Burgh lords of Connacht, the Burkes of Clanricarde. With the Gaelic O Kellys and O Maddens expanding from the east and regaining lost ground, the Walls survived on their lands about Kilreekill in close proximity to Loughrea, the centre of power of the Burke overlord of Clanricarde and in close proximity to the lands of the Anglo-Norman Dolphins.

Wall lands in the late 14th century

The Wall property in the late fourteenth century was described in a document relating to the revenues of the diocese of Clonfert as ‘the land of Claynaedy, alias de Valle, at Maenuagh.’[xii] (This latter appears to be ‘Moenmoy,’ the Anglo-Norman cantred about Loughrea and the wider territory wherein the O Naughtons and O Mullallys were said to have held sway prior to the arrival of the Anglo-Normans.) The Wall lands at that time were concentrated principally within the parish of Kilreekill, which then lay in the half barony of Athenry and would only later be included in the adjoining barony of Leitrim. Among the denominations in their territory from which the Church claimed an income were Trochte (Drought), Imleagh (Emlagh), Culfada (early modern quarter of Coolfadda) and Cathiragaraigh (Cahernagarry) and ‘‘Balleannabolgort and Rosscluaynmen’, all in the parish of Kilreekill.[xiii] Another denomination in the Wall’s territory that may also have been in that parish was ‘Ballenacircy alias Tyrol.’ Wall’s territory at that time also extended to the east into that part of the adjacent parish of Abbeygormacan that lay in the barony of Leitrim and included ‘Corballe’ (Corbally), ‘Corballenagall at Fennyr’ (Corballymore at Finnure), ‘Balleyogain’ (Ballyhogan) and the quarter of ‘Fynnuyrchuer’ (Finnure) and ‘Corracorrche’ (Cooracurkia).[xiv]

Phillip de Valle came to an agreement with Maurice O Kelly, Bishop of Clonfert, sometime between about 1378 and 1393 regarding Wall lands that were about that time forsaken or left waste and from which the Church was to derive a rental.[xv] The lands comprised ‘Fyndhuir’ (Finnure), ‘Corbaile,’ (Corbally) ‘Bayleyogan’ (Ballyhogan) and ‘Corchork’ (Cooracurkia), all of which lay in the parish of Abbeygormacan and on their eastern border with the O Maddens. [xvi]

The identity of Philip de Valle within the wider de Valle or Wall family is uncertain but he would appear to have been a senior, if not the senior-most, individual of the name in east Galway. The Annals of Connacht, in recording the occurrence of a great pestilence or plague in the territories of Conmaicne Cuile and Clanricarde in 1401, stated that Pilip a Fal (ie. Phillip de Valle or Wall) died of this plague. The Walls were not established in Conmaicne Cuile, a territory in the later County Mayo, which would suggest this plague victim was a prominent individual of the name in Clanricarde and so of the family established about Kilreekill.

Location of Wall territory about Kilreekill and Abbeygormacan (in green) in relation to adjacent families, the late medieval territory of the O Maddens to the east (in yellow) and various modern towns and villages in east Galway.

Burial place at Athenry

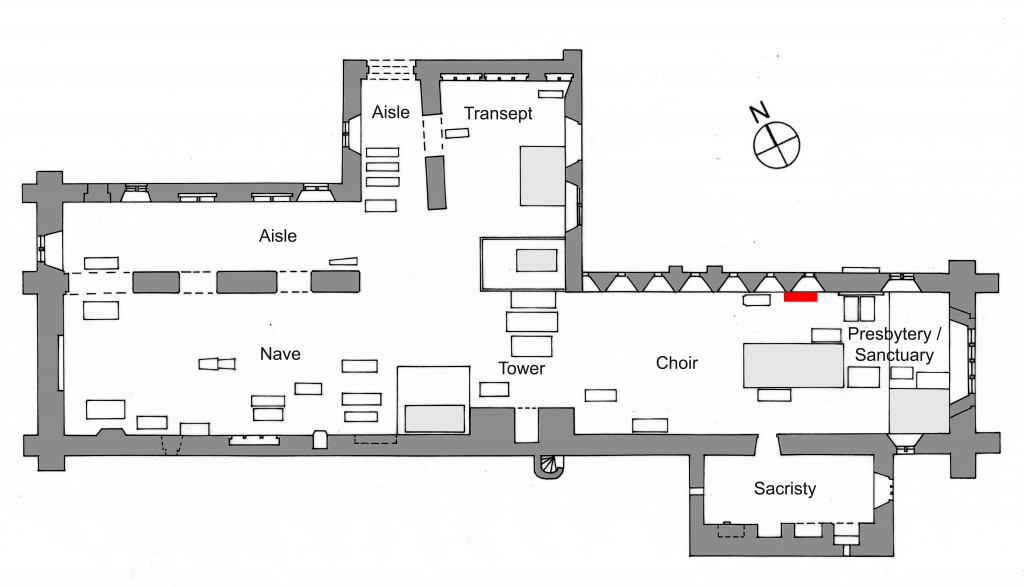

The prominent position of the Walls locally may be evidenced in the location of their burial place at the Dominican friary at Athenry. The Walls had long been associated with the friary, which had been founded by Meiler de Bermingham in 1241. Many of the high status burials were located about the choir or presbytery, in close proximity to the high altar. Their burial ground lay on the north side of the choir, approximately between the tomb of the friary founder and the north wall, adjoining which would be buried Thomas O Kelly, Bishop of Clonfert. The location of the Wall burials was marked by a triple-arched tomb built into the north wall of the choir. Among those of the family recorded as buried there before the mid fifteenth century were Gilbert de Wale and his wife Diruayl and adjoining them were buried Phillip de Wal and his immediate descendants.[xvii]

Location of the Wall family tomb at the Dominican friary, Athenry. (Plan of Church of SS. Peter and Paul after R.A.S. Macalister.)

Location of the Wall family tomb at the Dominican friary, Athenry. (Plan of Church of SS. Peter and Paul after R.A.S. Macalister.)

The Wall family tomb recessed into the north wall of the choir at Athenry friary. A stone tablet, bearing the arms of the Wall family and accompanying inscription, now supported on a stone ledge immediately on the left of the low triple-arched tomb recess, would appear to have been relocated to its current position in the twentieth century, as R.A.S. Macalister recorded its location under the central arch of the same triple-arched tomb when he visited the friary ruins about 1913. The now badly-defaced triple-arched tomb would therefore appear to have been the Wall family tomb repaired in the late seventeenth century by Walter, the son of Peter Wall.

Kilbocht friary

Within the Wall territory one Hugh or Hugo de Wall founded a friary for regular tertiaries or lay members of the Franciscan Order at Kilbocht, on a rise in the middle of the surrounding plain, within a short distance to the west of the Wall castle of Drought.[xviii] The friary was small in size, the nave of its church no wider than fifteen feet wide and approximately sixty-six feet or thereabout in length with a small side chapel. Little evidence, physical or written, would remain of the foundation but the friary, or at least a building thereof, would appear to have been extant in the early years of the sixteenth century as Matthew MacCraith, Bishop of Clonfert, died there in 1507.[xix]

The surviving ivy-laden walls of the church nave at Kilbocht, viewed from the fallen east gable wall.

In an environment where the Gaelic culture prevailed and distanced from the power of the English Crown, the descendants of the earlier Anglo-Norman settlers such as the Burkes, Walls and Dolphins, gradually adapted and adopted in varying degrees the customs of the native Irish. In all likelihood, one Willielmus de Valle, mentioned as one of seven arbitrators alongside Sir William de Burgo (Burke), ‘Captain of his Nation’ and others in a dispute of 1424 concerning the inheritance of one Henry Blake senior, a burgess of the town of Galway, was a senior member of this family.[xx]

Machaire an Fhaltaigh, ‘the plain of the Wall.’

By the later middle ages, at which time the effective power of the English Crown was confined to an area in the east of the country in the immediate vicinity of Dublin, the head of the Wall sept in Connacht was numbered among the ‘petty lords and captaines’ of the territory of Clanricarde in English documentation. With the heads of various families of Anglo-Norman descent by then known by such Gaelic titles as MacWilliam (Burke), MacFheorais (Bermingham), MacHubert (a branch of the Burkes), the head of the Walls was by that time identified by the English as ‘The Ffealtaghe’, an anglicised form of the Irish ‘An Fáltach’ or ‘The Wall’.[xxi]

The ancestral lands of the Walls, composed of twenty-four quarters of land in the half barony of Athenry was given in the late sixteenth century as ‘Magheryfaltaghe otherwise called Magheryaltaghe.’[xxii] This was an anglicised corruption of the Irish ‘machaire an Fháltaigh’, translating as ‘the plain of The Wall’ and as such was an accurate description of their patrimony. The area inhabited by the family formed a large plain about the parish of Kilreekill on the eastern border of the territory of Clanricarde, between the town of Loughrea and the territory of the O Maddens to the east.

Edmund and John fitzUllyke Valle or Walle of Maghareanaltay (i.e., Magheryfaltaghe) and John fitzJohn Walle of the same, gentlemen, were among a number of individuals pardoned by the Crown in October of 1551. In the case of the Walls, Edmund and John fitzUlllyke (ie. sons of Ulick) were pardoned for their slaying of their brother Ullyke. John fitzJohn appears to have been regarded as an accessory to the murder, described as being present when the crime was committed.[xxiii]

The castle of Drought

The principal residence of the head of the sept appears to have been the castle or tower house of Drought in the modern townland of that name, which was in ruinous state by the mid nineteenth century. A reference was made in the records of the Office of the Ulster King of Arms to the death in May 1561 of Ulick oge Wale of Droght in Co. Galway, who, by his wife Margaret Ny Bryan had at least one son, another Ulick, who was only four years of age at the death of his father. An inquisition taken twenty five years after Ulick oge’s death found that he had been seised in fee of the castle of Droght, together with a half quarter of land called Leighcarrowe Droght which were deemed free from all exactions. He was also seised in fee of the half quarter called Leighcarrowe Cowlyn, of a quarter called Carrowe Togher and of a cartron in Clonmean. The Earl of Clanricarde made annual demands and the Bishop of Clonfert rental demands from the same lands while Ulick oge himself made annual demands from certain lands in the territory of ‘Magheryaltagh’. The lands subject to Wall’s demands comprised four quarters of Balle Wolare, three quarters of Cowlefad, three cartrons of Kylmean, four quarters of Ballykylrickill and four quarters of Fynnoragh. Immediately upon Ulick oge’s death Walter Wall entered upon his castle and took possession of one half of the property. The other half of the castle was occupied in a similar manner by Ulick oge’s wife Margaret ny Bryan.[xxiv]

In 1574 Walter Wall was described as holding the castle of Drowghty, while John Wall was resident at Cowrly (possibly ‘Cowrte’ or Ballynecourt). That same year, John Wall, together with the head of the Dolphin family and Ulick óg beg Burke of Dunsandle, was listed as one of the chief men of the half barony of Athenry.[xxv]

The Earl of Clanricarde maintained a close relationship with certain of the principal members of the Walls in the late sixteenth century, with Richard 2nd Earl of Clanricarde choosing John or Shane Wall as the foster father of William Burke, one of his younger sons. That same William joined his brother John Burke in rebellion and when he gave himself up to the English authorities at Galway both he and his foster father were executed at the same time in that town in June of 1581. This John Wall resided as Ballynecourt, near Drought, as the inquisition taken in 1585 relating to his property described him as ‘of Ballyne Cowrt’ and prior to his attainder in May of 1581 and subsequent execution as having possessed, in addition to the castle and townland of Cowrte, lands in the immediate vicinity of that castle. Significantly in relation to the dating of that residence, the inquisition stated that the castle of Cowrte was built by the same John Wall but that about four or five years prior to John Wall’s attainder Walter Wall, ‘consanguineus’ or ‘cousin’ of John entered upon the castle and lands of John and occupied the same (but by what right the jurors of 1585 knew not). Following the attainder and the consequent forfeiture of the felon’s property to the Crown the same property was leased to Thomas Dillon, the Queen’s Justice of the Province of Connacht, who was holding it for the Queen at the time of the inquisition.[xxvi]

That same year of 1581 Ullyck oge Wale of Droght, Walter Wale of Droght, gentlemen and Sandell fitzJohn of the same were issued pardons alongside Redmond na scuab Burke of Clontuskert, brother of Richard 2nd Earl of Clanricarde.[xxvii] In 1582, among others issued a pardon were ‘Gilbert Wale of Maghair faltagh’, ‘Walter Wale McShane of Court’ and ‘Hugh boye Wale McShane of the same.’ Another of this family pardoned at that time may have been one identified only as ‘James mcShean of Court,’ while ‘John keoghe (ie. caoch or ‘blind’) Wale of Maghenalt’ was pardoned in 1584.[xxviii]

From the mid sixteenth century the officials of the Tudor Crown of England had made significant developments in extending the power of the monarch across the country. To finance their administration and military presence in Connacht, the Government resolved that a rent be agreed and charged from each division of land in the province. The rent would be payable to the crown, and called the Composition rent, after an agreement drawn up in 1585, between the Queens servants and the Connacht chieftains; the Composition of Connacht, effectively abolishing the various exactions and services imposed by the ruling Gaelic chieftain. By signing up to the Composition document, the signatories acknowledged their lands as private property, held under English law, in return for the agreed rent and on condition that they provide an agreed number of soldiers to support the administration when required. In so doing the signatories repudiated the Gaelic legal system in favour of that of England.

Walter Wall of Droghtye was described as chief of his name in the indenture relating to the territory of Clanrickard at the Composition of Connacht of 1585.[xxix] At this time, by letters patent dated July 1585, ‘all the lands, etc., whatever, spiritual and temporal in Droghtie, the castle of Court, Ballecowlefadd, Ballenawle, Ballekillrickell, Ballefennor, and elsewhere within the cantred and lordship or juristiction of Magherialtagh; which upon surrender were granted to Walter Wale of Droghtie and his issue male.’[xxx]

Within sixty years of the Composition the Walls would no longer be the principal landholders within their former territory. As early as January 1588 the Queen directed her Lord Deputy and Chancellor to make a grant to one John Rawson that would include ‘BallyCourte, with the lands thereto belonging in Maghery-Altough’.[xxxi] This was evidently part of the estate of John Wale of Ballynecourt (also given as Shane Wall of Courtwall), attainted for his part in rebellion against the Crown and whose lands were therefore declared forfeit. As the lands of this John Wall of Ballynecourt included the ‘castle’ of ‘Court’ or ‘Ballynecourt’ he was evidently that Shane Wall executed in 1581, and whose residence formed part of the property confirmed upon Walter Wall and his male issue in 1585. It is possible that this is the same ‘John Wall of Courtnewaltagh’ whose daughter Joane married Redmond Bermingham of Fenwoy in Co. Galway and by whom the same Redmond, who died in 1636 and was buried at the Cathedral in Tuam, had two sons and five daughters.[xxxii] The loss and redistribution of these Ballynecourt lands significantly diminished the power and influence of the principal family of the Walls locally, as the property and lands identified were these and other lands forfeited lay at the heart of their sept lands about Kilreekill.

Ballynecourt, parish of Kilreekill

Among the many to whom a general pardon was granted in 1603 in the first year of the reign of King James I were Ulick oge Walle of Droight and Redmond Walle of the Court, gentlemen.[xxxiii] It would appear that there were two principal residences in close proximity to one another within Machaire an Fhaltaigh; one at Drought and one at Ballynecourt, which also appears to have been known as Drumnecourty, Court, Courtwale or Courtnewaltragh. This latter would later be known by its English translation as the modern townland of Wallscourt.[xxxiv] Ballinecourt in the early seventeenth century was described as having a castle, containing a vault, a cellar, etc.’ and thereabout three cottages, twenty-five arable acres and seventy-six acres of pasture, mountain and bog and a mill-race ‘in Ballinecourte otherwise Courtmagheraltagh’[xxxv] It is likely that this building was located at the site of ‘Wallscourt House’, which would appear to have been a substantial house dating from at least the early seventeenth century and which lay in ruins in the mid nineteenth century.

Rawson may not long have held the lands granted him at Kilreekill as the lands about Ballynecourt were allocated to another following the accession to the throne of King James I. Among the vast tracts of land about the country acquired by in 1606 by the loyalist and land speculator Sir John King of Dublin was ‘half the town and lands of Coulfada and half quarter of land in the fields thereof and half quarter in Glannayne, a half cartron in Cartronclogh and a half cartron in Carrowboy, parcel of the estate of Shane Wall of Courtwall, attainted.’[xxxvi]

Acquisition of Wall lands by Robert Blake

The same estate at Kilreekill changed hands in May of 1612 when King James I granted to Robert fitzWalter fitzAndrew Blake of Galway, gentleman, a wealthy Galway merchant, lands in the half-barony of Athenry that included ‘the castle of Ballynecourt, three cottages, a water-course, where a mill was formerly built in the town of Ballynecourt, twenty five arable acres and seventy-six acres of pasture, mountain and bog, parcel of the estate of John Wale of Ballynecourt, attainted.’ In addition he received ‘half the town and lands of Coulfadda and a half quarter therein, half of the half quarter of land of Glanmyne, a half cartron in Cartronclogh and a half quarter in Carrowboy, parcel of the estate of John Wale of Courtwale, attainted.[xxxvii]

Among the lands granted Blake in the half barony of Athenry were ‘Eymellagh, one quarter; Knockanegilline, a half quarter; Lissenuske otherwise Lissemiskie, one cartron;[xxxviii] Carhinduff, a half quarter, lying in Ballydroghty; Meanseightragh and Meansoughtragh, one quarter;[xxxix] one quarter lying in Ballykillrickill; Cormanmore, one cartron in Cuolfadda; Carrowboy, a half quarter;[xl] Glannaskehy, one quarter; Bealanelare, one quarter in Ballynoulter; Lissenlooma, a half quarter; Leaghcarrowentobber, a half quarter lying in Ballyfunnor;[xli] Fieraghmore, one tenth of a quarter lying in the quarter of Carhaheyhunney; the quarter of Cahernegarry. Also, in the adjacent barony of Loughrea he was granted the castle, town and bawn of Carha and three cartrons. These he was to hold of the Earl of Clanricarde by knight’s service and a rent from every quarter.[xlii] Robert Blake was also granted among other lands in Counties Galway, Mayo and Meath an estate about Ardfry, which by coincidence was located in the parish also known as Ballynacourty, immediately south of the town of Galway, where his descendants would later be seated.

These lands combined consisted of much of the parish of Kilreekill and the wider ancestral lands of the Walls, from Cahernegarry in the west of the parish to Glennaskehy in the north, across through Ballinlaur, Kilreekill and Meanus to Finnure in Abbeygormican in the east of the Wall territory. By virtue of this grant and loans he extended to several of the more prominent Wall landholders, Blake effectively replaced the senior men of the Wall family as the principal landowner in what had formerly been Machaire an Fhaltaigh.

When he died in 1615 Blake’s will made provision for his lands in ‘Magheraltaghe in the barony of Athenry’ and the mortgages or rent-charges that he had there on the lands of Ulick oge Wall of Droghty and his son Shane Wall, along with significant other property elsewhere, to be bequeathed to his eldest son and heir Richard Blake of Ardfry.[xliii]

Among the many landholders of County Galway recorded as receiving a regrant of their lands from King James I there were few of the name Wall. Among those were Peter McEdmund Wall of Knockanekillin, gentleman, who held one half quarter of Knockanekillin in Athenry barony while Redmund Walle of Courtnewaltragh, gentleman, held one fifth of one half quarter in the parcel known as Feermore in Athenry barony.[xliv]

Lands detained from the Protestant Church

In enumerating the lands and rents detained from the See of Clonfert in 1615, Roland Lynch, Protestant Bishop of Clonfert, claimed the Walls as a sept possessed in that diocese Droghta, four quarters, Killrickill, four quarters, Balleinoulter, four quarters and Finiure, four quarters, and as a sept, with the exception of various branches of the O Maddens, detaining the largest area of land from the Bishop in the diocese.[xlv] As the Walls detained Finnure from the Church it would suggest that the lands to the west of Kilreekill, in the parish of Abbeygormacan, were still part of their territory at this time.

Walls about Kilreekill in the late 1630s

A number of the leading members of the family were still resident about Kilreekill and adhered to the Roman Catholic faith despite the efforts made in the early decades of the seventeenth century to identify and prosecute those who refused to attend Anglican services. Micheal Smith, an English-educated Protestant minister, who was appointed vicar of Kilreekill, reported twelve persons of varying social status who refused to attend the Protestant service held in the parish church in Killrickill on Sunday 22nd July 1632. Of this twelve, against whom Smith testified in court, the three of highest local standing were given as Ulicke Walle, John Walle and James Walle, all described as gentlemen, testifying to their continued refusal to convert and to their continued prominence locally. (It appears likely that Smith or at least members of his family may have resided locally as the lands of Nicholas Smith, ‘an English protestant, who resided at Walls Court, were plundered by men allegedly led by such prominent Galway landholders as Col. Richard Burke and John Daly of Benmore among others after the outbreak of the 1641 Rising. At that same time those of Michael Smith were likewise plundered by men led allegedly by John Madden of Longford.)[xlvi]

Robert Blake’s son and heir, Sir Richard Blake, knighted in 1624, was, alongside the Earl of Clanricarde, one of the largest individual landholders in the parish of Kilreekill in the heart of the ancestral lands of the Walls in the mid seventeenth century. His estate included that granted earlier to his father and by the late 1630s included others in the parish of Kilreekill such as the half quarter of Knockanekillin, formerly the estate of Peter McEdmund Wall. There were only about two landed proprietors of significance of the name Wall in the late 1630s, with their estates confined to the parish of Kilreekill. The largest landholder was one identified as ‘Mc Ulick oge Wall and another’, who with Sir Richard Blake, jointly held the quarter of Droughtie, the half quarter of Kilbought and the quarter of Cahirnegarrie. It is likely that this is Ulick oge Wall’s son and the same individual as John Wall Mc Ulick who also held the cartron of Gortneside in the same parish. The only other landed gentleman was Peter Wall, holding the quarter of Carra and the half quarter of Lislone located also in Kilreekill parish.[xlvii]

Cromwellian Period

A number of the Walls lost possession of their lands as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century, including one Walter Wall, who was simply given as ‘of County Galway’ when he was decreed 219 profitable Irish acres by the Cromwellians in May of 1656. Following the turmoil of that period and the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, an Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time.

‘Walter Wall of Carra’ was given as head of a family and one of the dispossessed landowners in 1664 whose lands was confiscated by the Cromwellian authorities and whose names were submitted to the Lord Lieutenant in that year for consideration for restitution.[xlviii] This Carra appears to be the modern townland of Carra, located in Kilreekill parish in the seventeenth century but given in the nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps as geographically situated in Kilcooly parish and belonging to the parish of Killoran. The same Carra in the seventeenth century records also state that while it lay in Kilreekill parish it was part of Killoran parish.[xlix]

By a decree of the Cromwellian Commissioners for transplanted persons, Walter Wall, together with one Brian O Brien were each adjudged a moiety (a half portion) of fifty-one acres in Caroegare and Castlequarter in the barony of Comcomroe in County Clare on 16th August 1677.[l] Wall was described as ‘of Carra, Co. Galway’ in 1684 when he leased the same Clare lands to John McDonough of Ballykeile in County Clare, implying that, despite the upheavals, he was at that time resident at Carra.[li]

It is likely that this is the same Walter Wall who was allocated an area of land in the quarter of ‘Clonmeane’ in the parish of Kilreekill after the demise of the Cromwellian regime and under the Act of Settlement.[lii] Dorothy Wall, relict of Walter Wall, prior to 1700, claimed as a dower 62 acres in Cloonamane in the half barony of Athenry.[liii]

One John Wall was also confirmed an estate under the Act of Settlement in the late seventeenth century, in the parish of Killyan in the half barony of that name, where, jointly with one John Sutton, he held lands of approximately two hundred and three profitable Irish acres in Carrowmore and Bonrom, two hundred and sixty six in the quarter of Carhownafrevy and other lands in that same parish. Their lands appear, however, to have been later acquired by the Hollow Blades Company at the end of the century.[liv]

Another individual of the name Wall, given as one John oge mc John mc James Bale, was proprietor of lands in the parish of Killoran in the barony of Longford in East Galway in the late 1630s.[lv] This would appear to be the same man as John Wall of Ballinroan, a denomination of land in that parish, who had his estate confiscated in whole or in part by the Cromwellian authorities and was by them allocated lands in Tynagh of 110 profitable Irish acres in June of 1656.[lvi] This same John Wall was confirmed in possession of a smaller parcel of land in the two quarters of Clonepreisk and Gortenery in that part of the parish of Tynagh that lay within the barony of Longford in east Galway.[lvii] His former lands in Killoran were confirmed under the same Act on others.

The Wall tomb at Athenry

During their time in the county the Cromwellian soldiers caused much damage to several religious houses including the Dominican friary at Athenry, where many of the tombs of the leading families of the county were located. Members of the principal family of the Walls were buried within the church of SS. Peter and Paul at that friary, their tombs location about the north wall of the choir, in close proximity to those of the Burkes of Clanricarde, the Berminghams and the Burkes of Derrymaclaughny, testifying to their prominent social position in the territory in the late medieval period. The Cromwellians ruined or defaced the Wall’s tomb during the destruction of the priory itself.[lviii] About thirty years later, in 1682, a memorial tablet was erected by Walter Wall ‘fich Peeter’ (ie. ‘fitz Peter’ or ‘son of Peter’) in place of the former, depicting the armorial bearings of the family and describing the family in Gaelic terms as ‘the sept of Walls of Droghty’.[lix]

In the late twentieth century the Wall armorial stone was supported on a stone ledge and set against the north wall of the choir of the abbey, to the left of a triple-arched arcade-tomb. When R.A.S. Macalister visited the ruins of Athenry Abbey about 1913 he recorded the Wall armorial stone as ‘built in under the central arch’ of this tomb, which would suggest that this arcade-tomb was that claimed by the Walls and the armorial tablet had been moved thereafter.

Walter Wall’s taking it upon himself to restore the tomb of his ancestors would suggest that he may have been the principal representative of the name in the late seventeenth century and was likely to have been Walter Wall of Carra.

Baron Wallscourt of Ardfry

Under the Acts of Settlement following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Robert, son and heir of Sir Robert Blake of Ardfry, obtained from the Crown a re-grant of his family’s former estates. In early 1681, in addition to the lands about Ardfry and elsewhere in Counties Galway, Mayo and Meath, he was re-granted the former lands of the Walls about Kilreekill.[lx] The 1681 re-grant mirrored closely the original grant of 1612 to his grandfather, with almost all the denominations about Kilreekill accounted for in the later grant. On this occasion, however, Carra does not appear to have been part of the Blake estate. The quarter of Droghty, which his father previously jointly held with the son of Ulick Wall before the Cromwellian period and the cartron called Gortneside or ‘Garnesidy’ previously held by John son of Ulick Wall were in their entirety among Robert Blakes 1681 lands as was that of Ballynecourty which was described as ‘Wallscourt alias Drumnecourty alias Ballynecourty.’[lxi]

While the Wall family declined in significance in their former territory, the name continued in the title granted to a later Blake associated with the lands, when, in 1800, Joseph Henry Blake of Ardfry, one time M.P. for County Galway in the Irish Parliament was created Baron Wallscourt of Ardfry.[lxii] A direct descendant of Sir Robert Blake, his title derived from the two large estates the family had acquired in 1612, that of Ardfry and the ancestral lands of the Walls about Kilreekill.

For the arms of the principal line of this family, refer to ‘Wall’ under ‘Heraldry.’

[i] N.L.I., Dublin, G.O. Ms. 160, pp. 40-44; Burke, B., The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales comprising a registry of armorial bearings from the earliest to the present time, Harrison and sons, London, 1884, Vol. III, p. 1066.

[ii] Curtis, E. (ed.), Calendar of Ormond Deeds, Vol. i, 1172-1350 A.D., Dublin, I.M.C., 1932, pp. 67-8.

[iii] Walsh, T., History of the Irish hierarchy with the monasteries of each county, biographical notes of the Irish saints, etc., D. & J. Sadlier & Co., New York, 1854, p. 444. Corbellynegall or ‘Corbally of the foreigners’ appears to be a reference to Corballymore in the early modern parish of Abbeygormacan. In the 1407 Episcopal Rentals of the Diocese of Clonfert this denomination is given as ‘Corballimore nangall’ and listed alongside a number of others about the parish of Abbeygormacan. (Nicholls, K.W., The Episcopal Rentals of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, IMC, 1970, p. 138.) The townland of Corballybeg lies near Corballymore in that parish but this appears as early as 1407 as a separate and distinct townland and would appear to be that ‘Cluain Idolsy alias Corballibeg’ listed in the 1407 Rentals immediately before Corballimore nangall. Another Corballybeg and Corballymore were located in the parish of Doonanoughta.

[iv] Sweetman, H.S. (ed.), Calendar of Documents relating to Ireland preserved in Her Majesty’s Public Record Office, London, 1302-1307, London, Longman & Co., 1886, p.136. No. 436. Dated July 4th 1305.

[v] Mills, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Justiciary Rolls or proceedings in the court of the Justiciar of Ireland, Edward I, Part 2, XXXIII to XXXV years, London, A. Thom & Co. Ltd., 1914, p. 278. The lands are unidentified but as the lands are described as bordering the lands of the Irish, from the placename ‘Camas’, usually indicating a winding stream or river and on the basis that part of Hynchecoulcass may be a reference to an ‘Inis’ or ‘Inch,’ indicating the presence of an island or low meadow along a riverside, it is possible that the march or border was formed by an adjacent stream or river. One Robert Gent accounted for rent of a carucate of land at Molaghmokys, in the County of Roscommon about 1324 or 1315. (The Thirty-ninth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records and the Keeper of the State Papers in Ireland, Dublin, Alex Thom & Co., 1907, Appendix, ‘Accounts of the Great Rolls of the Pipe of the Irish Exchequer for the reign of Edward II.’ Pipe Roll, a.r. viii, Ed. II, (no. 42.), p. 54.)

[vi] Holland, P., The Anglo-Norman landscape in Co. Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 49, 1997, pp.159-193.

[vii] Mills, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Justiciary Rolls or proceedings in the court of the Justiciar of Ireland, Edward I, Part 2, XXXIII to XXXV years, London, A. Thom & Co. Ltd., 1914, pp. 44, 125.

[viii] Mills, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Justiciary Rolls or proceedings in the court of the Justiciar of Ireland, Edward I, Part 2, XXXIII to XXXV years, London, A. Thom & Co. Ltd., 1914, pp. 465-6.

[ix] Mills, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Justiciary Rolls or proceedings in the court of the Justiciar of Ireland, Edward I, Part 2, XXXIII to XXXV years, London, A. Thom & Co. Ltd., 1914, p. 341. 35 Edward I.

[x] Connolly, P., An Account of Military Expenditure in Leinster, 1308, Analecta Hibernica, No. 30, 1982, pp. 1, 3-5.

[xi] Holland, P., The Anglo-Norman landscape in Co. Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 49, 1997, pp.159-193.

[xii] Nicholls, K.W., The Episcopal Rentals of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, IMC, 1970, pp. 139-140.

[xiii] Balleannabolgort was identified by K.W. Nicholls as the prebend of that name, also called ‘Ballenoulloryt,’ ‘Ballynnadbuloyrt’ or ‘Balenoulter,’ which comprised the modern townlands of Ballintober East and West, Ballinlaur and Glennaskehy, all in the northern end of Kilreekill parish. The obsolete fifteenth century prebend of Culfada he identified as including the modern townland of Doon and adjacent townlands in that same parish. (Nicholls, K.W., Rectory, Vicarage and Parish in the Western Irish Diocese, J.R.S.A.I., Vol. 101, No. 1, 1970, p. 80.)

[xiv] Nicholls, K.W., The Episcopal Rentals of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, IMC, 1970, pp. 139-140.

[xv] The date of the agreement may be regarded as having occurred between these dates, the year in which Bishop O Kelly was consecrated Bishop of Clonfert and the year in which he was translated thereafter to Tuam. He was, however, appointed before March 1378 but consecrated in March.

[xvi] Nicholls, K.W., The Episcopal Rentals of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, IMC, 1970, pp. 139-140.

[xvii] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, pp. 212-3.

[xviii] Ó Clabaigh, C., The Mendicant Friars in the medieval diocese of Clonfert, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 59, 2007, p. 31.

[xix] Ó Clabaigh, C., The Mendicant Friars in the medieval diocese of Clonfert, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 59, 2007, p. 31.

[xx] Hardiman, J., A Chronological description of West or h-Iar Connaught, written A.D. 1684 by Roderick O Flaherty Esq., author of the ‘Ogygia’, edited from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College Dublin, with notes and illustrations, Dublin, Irish Archaeological Society, 1846, p. 201-202.

[xxi] Hardiman, J., A Chronological description of West or h-Iar Connaught, written A.D. 1684 by Roderick O Flaherty Esq., author of the ‘Ogygia’, edited from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College Dublin, with notes and illustrations, Dublin, Irish Archaeological Society, 1846, p. 323-6.

[xxii] Hardiman, J., A Chronological description of West or h-Iar Connaught, written A.D. 1684 by Roderick O Flaherty Esq., author of the ‘Ogygia’, edited from a manuscript in the library of Trinity College Dublin, with notes and illustrations, Dublin, Irish Archaeological Society, 1846, p. 323-6.

[xxiii] Morrin, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Patent and Close Rolls of Chancery of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, Vol. I, Dublin, Alex, Thom & sons, 1861, p. 249. pardon dated, October 27th, 5th Edward VI; The Irish Fiants of the Tudor Sovereigns during the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Philip and Mary and Elizabeth I, Vol. 1, 1521-1558, Dublin, Edmund Burke Publisher, 1994, p. 632.

[xxiv] N.L.I., Dublin, G.O. Ms. 218, p. 304; National Archives, Dublin, R.C. 9/14 Repertories of Inquisitions (Exchequer), Vol. 14, County Galway, Eliz.–Wm. III, pp. 83-87.

[xxv] Nolan, J.P., Galway Castles and Owners in 1574, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. I, 1900–1901, No. ii, pp. 109-123.

[xxvi] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of the State Papers relating to Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth 1574-1585,London, Longman, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1867, p. 308; National Archives, Dublin, R.C. 9/14 Repertories of Inquisitions (Exchequer), Vol. 14, County Galway, Eliz.–Wm. III, pp. 35-36.

[xxvii] Fiants Eliz. I

[xxviii] Calendar of Fiants Queen Elizabeth I, The thirteenth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records in Ireland, 12 March 1881, Dublin, A. Thom & Co., 1881, Appendix, p. 193-4:The Irish Fiants of the Tudor Sovereigns during the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Philip and Mary and Elizabeth I, Vol. 2, 1558-1586, Dublin, Edmund Burke Publisher, 1994, p. 632.

[xxix] O Flaherty, R., A Chronological Description of West or h-Iar Connaught, Dublin, Irish Archaeological Society, 1846, pp.323-4.

[xxx] Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland, 1800, 13 James I, Part 1, pp. 281.

[xxxi] Calendar of the Patent and Close Rolls of Chancery in Ireland from the 18th to the 45th of Queen Elizabeth, Vol. II, Dublin, A. Thom, 1862, January 13th (1588), 13th Eliz. The lands at BallyCourte and other lands about the country were granted at that time to Rawson in recognition of his having given up the ‘customership’ of Athlone, ‘appertaining to the manor House there.’

[xxxii] N.L.I., Dublin, G.O., Ms. 70, Funeral Entries, p. 133. No arms, impaled or otherwise, were depicted in this funeral entry.

[xxxiii] Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland, 1800, I James I, Part I, pp. 18-20.

[xxxiv] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, p. 284.

[xxxv] Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland, 1800, 13 James I, Part 1, pp. 281

[xxxvi] Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland, 1800, 3 James I, p. 81.

[xxxvii] Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland, 1800, I0 James I, Part 4, pp. 223-4. Also Blake, M.J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, London, Elliot and Stock, 1905.

[xxxviii] This would appear to equate with the modern townland of Glenmeen in the parish of Kilreekill, wherein lies a ringfort called Lissaniska. The townland of Glenmeen was given in 1612 as ‘Glanmyne.’

[xxxix] Meanseightragh and Meansoughtragh, ie. Meanus iochtarach and Meanus uachtarach, ‘Meanus Lower’ and ‘Meanus Upper.’ Identified in a later 1681 re-grant as ‘Meanes’, this is the modern townland of Meanus, upon the border of which with the townland of Lecarrownacappoge and the modern townland of Wallscourt (formerly ‘Ballynecourty’ or ‘Ballinecourt’) the village of Kilreekill developed.

[xl] Carrowboy is identified as the modern townland of Newgrove in the parish of Kilreekill. (Blake, M.J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, London, Elliot and Stock, 1905, p. 91.)

[xli] This half quarter called Leaghcarrowentobber ‘lying in Ballyfunnor’ would appear to be the modern townland of Carrowntobber in the parish of Abbeygormican, barony of Leitrim, which lies near the modern townland of Finnure and wherein a number of wells known as St. Brendan’s wells and a cross were once situated. A later 1681 re-grant of much of these same lands makes reference to a quarter of land called ‘Ballintobber alias Carrowntobber’ which may be the denominations known as Ballintobber East and Ballintobber West in the parish Kilreekill, in which lay a well known as Tober grellaun, ‘the well of Grellan or St. Grellan.’

[xlii] Calendar Patent Rolls,10 James I, p. 224, dated 16th May 10th. In June of 1615, Sir John Kinge and Sir Adam Loftus were granted half of Coulfada and three quarter parts of a quarter in the same, half of the half quarter of Clanmine, a half cartron of Cartronclough, a half quarter of Carrowboy, with a crown rent payable, parcel of the estate of John Wale of Courtwale, attainted and the castle of Ballinecourt, containing a vault, a cellar, etc. and three cottages, 25 arable acres and 76 acres of pasture, mountain and bog and a mill-race in Ballinecourte otherwise Courtmagheraltagh, parcel of the estate of the said John Wale. Also they were granted at that time for a Crown rent ‘all the lands, etc., whatever, spiritual and temporal in Droghtie, the castle of Court, Ballecowlefadd, Ballenawle, Ballekillrickell, Ballefennor, and elsewhere within the cantred and lordship or juristiction of Magherialtagh; which upon surrender were granted to Walter Wale of Droghtie and his issue male, by patent, dated 27July 26th Eliz.’ A Crown rent was payable on all of these lands. (Calendar of the Patent Rolls of the Chancery of Ireland, 1800, 13 James I, Part 1, pp. 281) These lands correspond closely with those granted to Robert Blake in 1612 and which were re-granted to his grandson in 1681.

[xliii] Blake, M.J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, London, Elliot and Stock, 1905, pp. 247-250, Appendix. The will of Robert Blake fitzWalter fitzAndrew, Galway, merchant.’ Robert Blake made provision that his eldest son Richard, later knighted by the Lord Deputy in 1624, would inherit ‘my land sin magheraltaghe in the barony of Athenry that I have in fee simple or free-farm, my mortgage or rent charge that I have there upon Ulick oge Wall of Droghty for 40 marks and of his son Shane wall for 10 marks.’

[xliv] Cal. Pat. Rolls, 17 James I, p. 440.

[xlv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Royal Visitation of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, 1615, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 35, 1976, p.72.

[xlvi] B. MacCuarta S.J. (ed.), A presentment of Recusants, East Galway, 1632’, JGAHS, Vol. LXI, 2009, pp. 74-78. The lands of the same Michael Smith, later Archdeacon of Clonfert, were spoiled by John Madden of Longford in December of 1641 on the outbreak of the rebellion of that year; Tallon, G. (ed.), Court of Claims, Submissions and Evidence 1663, Dublin, I.M.C., 2006, p. 281.

[xlvii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 314-315.

[xlviii] The Irish Genealogist, Vol. 4, p. 275.

[xlix] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. 315.

[l] N.L.I., Dublin, Inchiquin Papers (compiled by B. Kirby, 2009), Collection List No. 143, Ms. 45,142/7, p. 126.

[li] J. Ainsworth (ed.), The Inchiquin Manuscripts, Dublin, Stationary Office for the Irish Manuscripts Commission, 1961, p. 406.

[lii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. 316.

[liii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 207. Entry no. 1838.

[liv] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. 258-260.

[lv] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962,

[lvi] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. 157; Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Marquess of Ormonde K.P., Presented at Kilkenny Castle, Vols. I, II, III, Historical Manuscripts Commissions, Fourteenth Report, Appendix, Part VII, London, Eyre and Spottiswode for Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1895, p. 176. ‘List of Transplanted Irish 1655-1659, No. 1, ‘An account of lands set out to the Transplanted Irish in Connaught.’

[lvii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p.202.

[lviii] The destruction of the burial place was recorded on the replacement memorial erected in place of the original; ‘Here is the antient sepulchre of the sept of Walls of Droghty…demolished by Cromwellians and re-edified by Walter Wall…’

[lix] Macalister, R.A.S., The Dominican Church of Athenry, J.R.S.A.I., Sixth Series, Vol. III, No. 3, 1913, p. 221.

[lx] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, p. 284.

[lxi] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, p. 284.

[lxii] Blake, M. J., Blake Family Records 1600-1700, Second series, London, Elliot Stock, 1905, pp. 179-184.