© Donal G. Burke 2017

The following is a selection of the memorials erected at the former Franciscan friary of Kilconnell. Various memorials in this friary were recorded in Volumes 1 and 2 of the Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead in Ireland and in Volumes 1 and 2 of the Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society.

I

Existing memorials within church nave and chancel

The ruins of Kilconnell friary

Sir Thomas Molyneux, Bart., visiting the ruins of the Franciscan friary at Kilconnell in April of 1709, noted that ‘their churchyard is surrounded by a wall of dead men’s sckulls and bones pil’d very orderly with their faces outwards, clear round against the wall to the length of 88 foot, about 4 ft. high and 5 ft. 4 in. broad, so that there may be possibly here to the number of 50,000 sckulls; within they shew you Ld. Gallway’s and other great men’s heads killed at Aghrim. (Molyneux appears to have attempted to give an accurate description of the wall of bones, using his cane, ‘2 ft. 8 in. long’ as his measuring stick.) ‘This abbey was in good repair’ he noted, ‘and inhabited by Fryers in K. James time, so that some of the woodwork, the wainscot, and ordinary painting yet remains: nay I am told 2 of ye Fryers are yet alive, and live, tho’ blind with age, on ye charity of the neighbouring papists, in a poor cabin, in a very small island, which they showed me, not ½ a mile from Kilconnell in a bog; they employ one to beg for them, and by that means subsist near their old habitation’.[i] The Rev. Charles P. Meehan in his ‘Rise and Fall of the Irish Franciscan Monasteries’, first published in 1869, states that the bog upon which the friars took refuge after the battle of Aughrim was known in his time as ‘The Friar’s Bog‘. Expanding on this, Francis G. Biggar in his 1902 article on the friary in the Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society commented that this bog was a ‘pasture field’ near the house of a man surnamed Blaken in the previous year. Situated, he said, about half a mile north of the friary, Biggar noted that it was in 1901 called ‘Monambraher Friary’ on the Ordnance Survey map. He was of the opinion that this was so recorded on the map at the instigation of the antiquary John O Donovan, who had recorded in his Ordnance Survey Letters of 1838 that an abbey bell was found in ‘Moin na-mbrathair’ (ie. bog of the friars) in the townland of Ellagh, near Kilconnell. O Donovan confirmed the tradition that the friars, after Aughrim, fled to Moin na-mbrathair’, wherein they built cottages but he added that they remained there until fifty-four years prior to his visit, ie. about 1784.

Of the wall of skulls and bones, there is no indication of its existence or survival intact in the late eighteenth century as such a feature may have been expected to appear in Francis Grose’s depiction of the ruins in his ‘Antiquities of England and Wales’ of 1786 and O Donovan made no reference to any such osteal wall in the 1830s. However, it does appear that some considerable number of skulls and bones were strewn about the site into the nineteenth century as Biggar noted that they ‘lay about in heaps’ until some time about 1860 or 1870 when ‘Lord Clonbrock and some local gentlemen got some sort of decency brought about, which if not resisted was barely tolerated by the peasantry’.

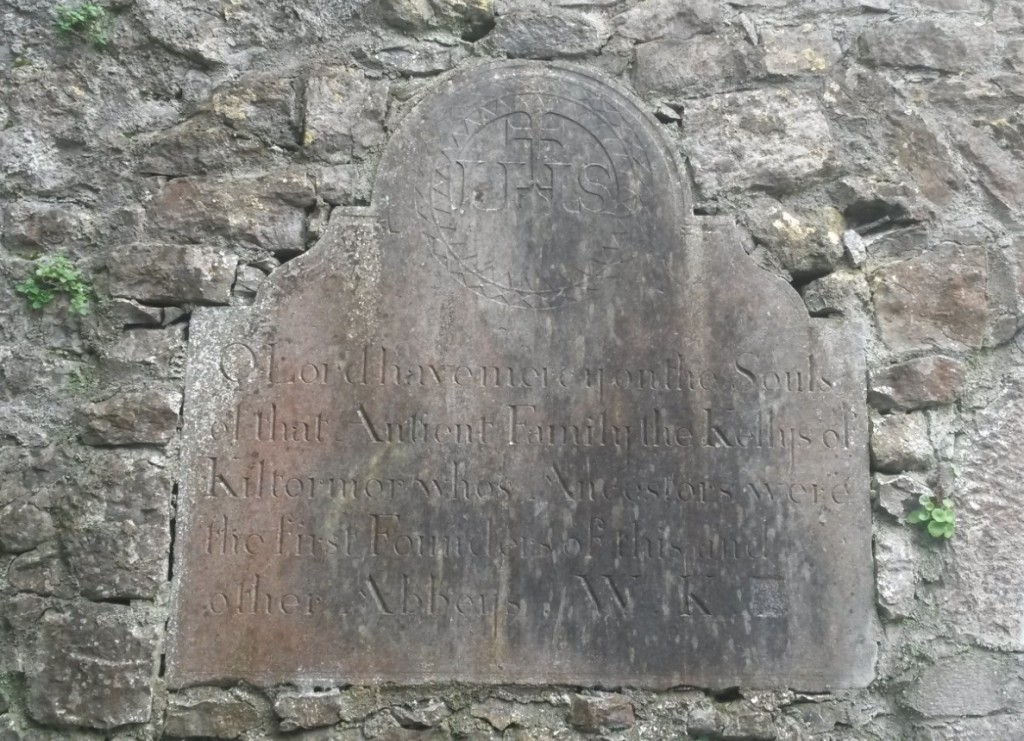

A stone tablet set in the south wall of the chancel, near the east window:-‘IHS O Lord have mercy on the Souls of that Antient family the Kellys of Kiltormer whos Ancestors were the first Founders of this and other Abbeys. WK’

This memorial was evidently erected prior to 1838 as John O Donovan recorded the inscription thereon during his visit of October of that year. Samuel Lewis in his 1837 ‘Topographical Dictionary of Ireland’ gave the village of Kiltormer-Kelly as lying within the parish of Kiltormer in County Galway. The village is now known simply as Kiltormer. While much of the land about the parish of Kiltormer in the mid-nineteenth century formed part of the estate of the Cromwellian Eyre family resident at Eyreville, Lewis described the village of Kiltormer-Kelly as located on the estate of Charles Kelly, ‘a friar, whose ancestors founded Kilconnell Abbey and some others in this country.’

The friar and Kelly family to whom Lewis made reference resided in the mid-nineteenth century at Bettyville, in the nearby townland of Cloonlahan (Eyre) in the parish of Killoran, adjacent to that of Kiltormer. The family and estate papers of the Eyre family of Eyreville, at Kiltormer, contain several documents which make reference to a Kelly family holding land adjacent to the Eyreville estate from the late seventeenth century and into the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. While the documents do not provide sufficient detail to provide a continuous pedigree of the Kelly family throughout that period, the earliest member appears to have been Bryan mcShane O Kelly of Urachree whose estate in the parish of Clontuskert was confiscated in whole or in part by the Cromwellians in the mid 1650s and who was allocated approximately thirty-one profitable Irish acres in the quarter of Kiltormer. He was described as of Kiltormer in the marriage agreement drawn up in 1678 between him and William Cahan of County Sligo, relating to the prospective marriage of Bryan mcShane’s son and heir apparent Hugh Kelly mcBryan and Cahan’s daughter Margaret.[ii] Hugh Kelly mcBryan came to reside at Tonrogee (apparently the modern townland of Tanrego) and later at ‘Balliowaghane’ in County Sligo but leased his lands about Kiltormer for a time about 1696 to Captain Samuel Eyre of Eyrecourt, who later founded the Eyreville branch of that family. Hugh’s widow Margaret, who had an interest in the same Kiltormer lands ‘by right of her dower’ leased the same lands in 1722 to Eyre, then of Newtown or Eyreville for the duration of her natural life. While Hugh and Margaret Kelly’s son Peter appears to have been living in County Sligo in 1722, members of the family retained an interest in the Kiltormer lands, with Thady Kelly making representation in 1772 to Samuel Eyre the younger regarding the lands which had previously been set to Samuel the younger’s uncle Col. Stratford Eyre. The Kelly lands lay in what became known as the modern townland of Kiltormer West and upon which developed the small village of Kiltomer. John A. Kelly appears to have been a senior member, if not the senior-most member of the family leasing lands at Kiltormer West at the end of the eighteenth century.

In April 1836 Charles Kelly, ‘Dominican Fryar’ (to whom Lewis made reference in his Topographical Dictionary of the following year) and Malachy Kelly, both with an address of ‘Bettyville, Aughrim,’ were among five Catholic clergymen, one Protestant clergyman and five ‘lay gentlemen’ who appended their names to an appeal for clemency to the Lord Lieutenant and Governor General of Ireland, requesting the commutation of the sentence imposed on two local boys from Transportation for Life to Imprisonment. Malachy Kelly, when writing to Ambrose Madden of 112 Talbot Place, Dublin in January 1843, gave his address as ‘Bettyville, Kiltormer’ and informed Madden that ‘Fr. Charles’ had died but that the rest of the family were well.[iii] The Freeman’s Journal dated 27 August 1846 recorded the death at Bettyville of Malachy Kelly Esq. at the age of eighty years.

This Kelly family of Bettyville, evidently descended from the Kellys of Urachree, who were a minor sept of the wider O Kelly family of Uí Maine by the early seventeenth century, were clearly the same family of Kiltormer who had the memorial stone erected at Kilconnell. While they were descended from individuals who may have ruled the territory of Ui Maine at some distant stage, there were a number of more senior branches of the name, closer in line to the last ruling chieftains who may have had a stronger claim to precedence in erecting a memorial to their ancestors who founded the friary at Kilconnell.

The ruins of Bettyville, near Kiltormer in the early twenty-first century.

Flamboyant tomb in nave at the west door

It is not known with certainty to whom this tomb belonged or the identity of its occupant or occupants. The only part of the inscription decipherable in 1901 when Francis Joseph Biggar described the tomb was given as ‘V D MONUMENTUM EJAM ETIAM’. He described the canopy as flamboyant in nature and the front divided into six panels, ‘each one filled with a saintly figure, surmounted by their respective name, which are as follows:- Sanct. Johannes, Sanct. Lodouic, Sancta Maria, Sanct. Johanes, Sanct. Jacoib, Sanct. Dinais. The finial is divided into two panels, in the one on the left is the figure of a bishop, with a crozier in his left hand, the right hand with the three fingers uplifted in the act of blessing. The panel to the right has the figure of an Abbot with a plain staff in his right, blessing with his full right hand’.[iv]

Brendan Jennings opined in a 1945 article in the Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical society that this tomb may have been that built for his own internment by Bishop Boetius MacEgan OFM who died in 1650.[v] Boethius MacEgan, a Franciscan friar, was appointed Bishop of Elphin in 1625. John Lynch, Archdeacon of Tuam in his 1672 Ms. ‘De Praesulibus Hiberniae’ recorded that ‘for not ignoring that death was approaching he took care a tomb should be erected for himself, at his own expense, in the ‘capitulo’ of the Kilconnell Convent, into which convent he betook himself for two years before his death, so that he might be at liberty the more studiously to procure the salvation of his soul, where in the seventieth year of his age, after duly administering the diocese for thirty-five years, he changed this life, as we trust, for a better one, on Low Sunday 1650’.[vi] Bigger took this ‘capitulo’ to indicate the ‘chapel’ of the friary while Jennings took this to have indicated the ‘chapter room’. The location is uncertain from this source as, while ‘chapter room’ may be a closer translation of the original note, Jennings acknowledges that it was unlikely that a tomb was constructed in a chapter room.

Jennings was of the view that the Bishop may have been interred in the flamboyant west door tomb, based on the importance of its architectural form, the fact that one of the two carved figures at the finial is a bishop carrying a crozier and that the corresponding finial figure may have been that of St. Francis with habit. These he felt were ‘symbols which might appropriately appear on the monument of a Franciscan bishop and as no other Franciscan bishop but Boetius MacEgan is known ever to have been buried at Kilconnell’ he felt that ‘further investigation on these lines might lead to a definite decision’.[vii]

The two figures either side of the finial of the west door tomb, that of the left evidently a bishop with mitre and crosier, that on the right, which Biggar may have found difficult to inspect from ground level, is undoubtedly St. Francis, bearing the stigmata with the wounded side visible through his habit. Similar depictions of the saint are to be found surviving from several other Franciscan foundations including Meelick in East Galway.

While Jennings argument is compelling for the west door tomb as the possible resting place of a bishop, its architectural form more reflects the style of the early sixteenth century and would appear to contradict its construction by Bishop Egan. Its form is much closer to that of a late medieval tomb than that fashionable about the mid seventeenth century, when Bishop MacEgan commissioned his own tomb.[viii] Jennings was aware also that there is a ruined tomb in the transept of the church, part of which appears to have once been part of the Bishop’s tomb, bearing as it did the inscription; ‘Orate pro anime reverendissimi dom(ini) ac fratris nostri Boetii Egan’ but was of the view that this part of the tomb had become detached from the original monument and found its way to the transept tomb at some stage. This transept grave, he noted, was that of one Michael Dalton of Raara.

While the location of Bishop MacEgan’s tomb is still not known with any certainty, its use in the early eighteenth century was the cause of some controversy and implies that it was not only still then known but was intact. The issue arose in the early 1720s when a ‘strong report was lately spread abroad among ye secular benefactors (of the friary) and even Doctor Edmond Kelly ye present Lord Bishop of Clonfert’ that the friars and their guardian Fr. Anthony Kelly senior consented to the burial of Mrs. Mary Hamiltion alias Kelly of Lisduff ‘in ye tombe erected formerly by my Lord Bishop Boetius Egan of Elphin’. In the presence of Commissary Visitator Fr. Francis Keally on 20th May 1723 twelve friars at Kilconnell appended their signatures to a document denying that they ever gave consent to that burial in that tomb and went further, railing ‘against all right or title whatsoever yt may be hereafter pretended by ye family of Lisduff, or theire adherants, allys, or relatives’.[ix]

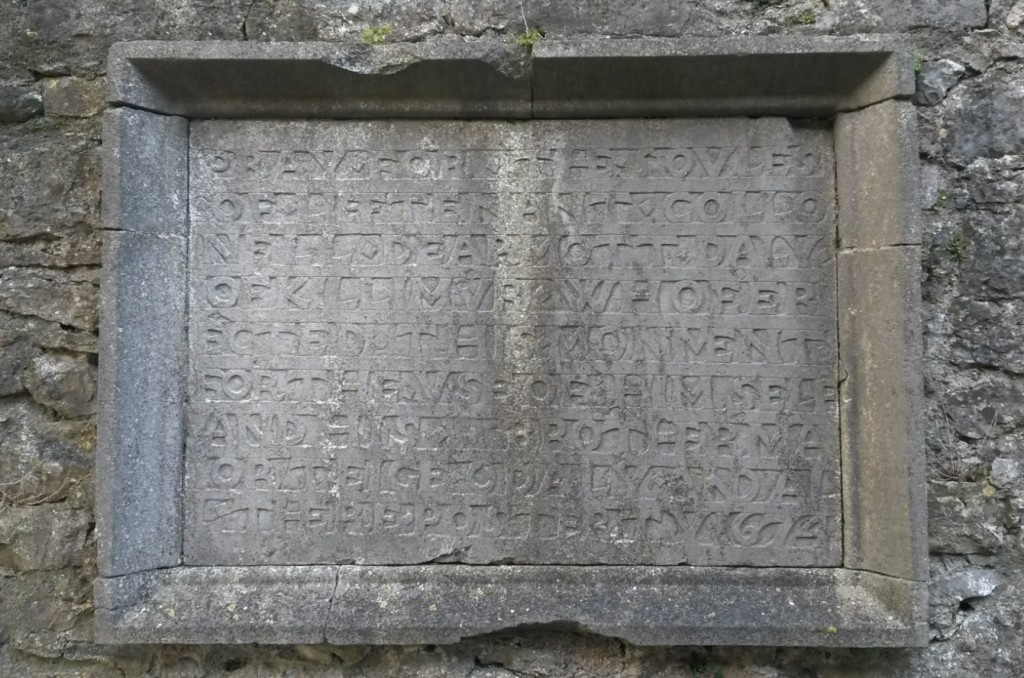

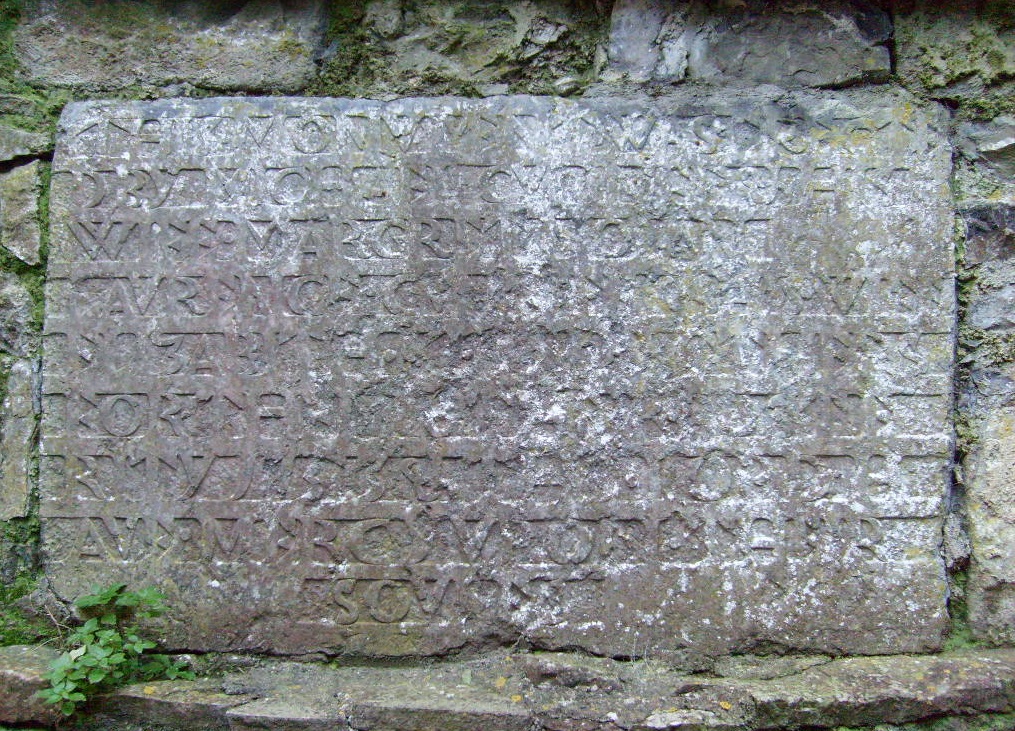

On a large stone tablet in raised lettering on the north wall of the chancel:-‘Pray. for. the .sovles. of. Lieftent. Collonell. Dearmott. Daly. of. Killimvr. whoe. erected. this. Monment. for. the. vse. of. himself. and. his. brother. Maiior Teige O Daly. and. all there posterity 1674’.

Lieut. Col. Dermot Daly of Killimor or Killimordaly was the great grandson of Dermot O Daly, believed to have been the first of his family to settle in County Galway, who received a grant of the Manor of Laragh in County Galway in 1578 and who died in 1614. Martin J. Blake, in his article on the ‘Families of Daly of Galway with Tabular Pedigrees’ (JGAHS, Vol. XIII, 1919-1920, p. 140) gave the erector of the memorial, who died in 1699, as the eldest son of Donagh, son of Teige O Daly, who were in their respective generations the senior-most descendant of that Dermot O Daly of Laragh and Killimor who died in 1614. His grand-uncle, Dermot O Daly, second son of Dermot of Laragh and Killimor, served as a captain in the Royalist army and was responsible for the defence of Tirellan castle in 1642. That grand-uncle may also been that Major Dermot O Daly whose troops were besieged in the friary of Kilconnell by Cromwellian forces in 1651.

An account of the defence of Kilconnell by O Daly and his soldiers was given twenty-one years later by John Lynch in his aforementioned ‘De Praesulibus Hiberniae’ . In that account he relates that the Cromwellian ‘horse and foot, stubbornly assaulting the monastery of Kilconnell, stoutly attacked two or three troops of the confederates, which Dermot O Daly commanded as Major. But the besieged bravely repelled the hostile attack as long as gunpowder lasted, and when destitute of gunpowder with rocks and the skulls and bones of the dead hurled against the besiegers, they for some time drove them from the approach, when a a woman, graceful in excellent beauty of form, showing herself to the soldiers so as to be seen, supplied gunpowder to the soldiers, man by man, from an apron, the whiteness of which the nitrate powder did not darken in the blackness. At length on a wild night, the besieged taking care, the pealing of the greater bell, a very brisk rattling of the drums, and a hasty sound of the musical trumpet, burst forth with a tumult, which struck such fear to the besiegers that, persuading themselves that by that signal the neighbouring inhabitants were being summoned to bring present aid to the besieged, turned suddenly away into flight, they raised the siege and never afterwards returned to attack the monastery. Whence a pious persuasion settled in the minds of many that the prayer of either the prelate lately buried in it (ie. Boetius Egan, buried the previous year), or of others interred in it, had obtained for the monastery that safety, because had it been then assaulted, beyond doubt it had been leveled to the ground.’

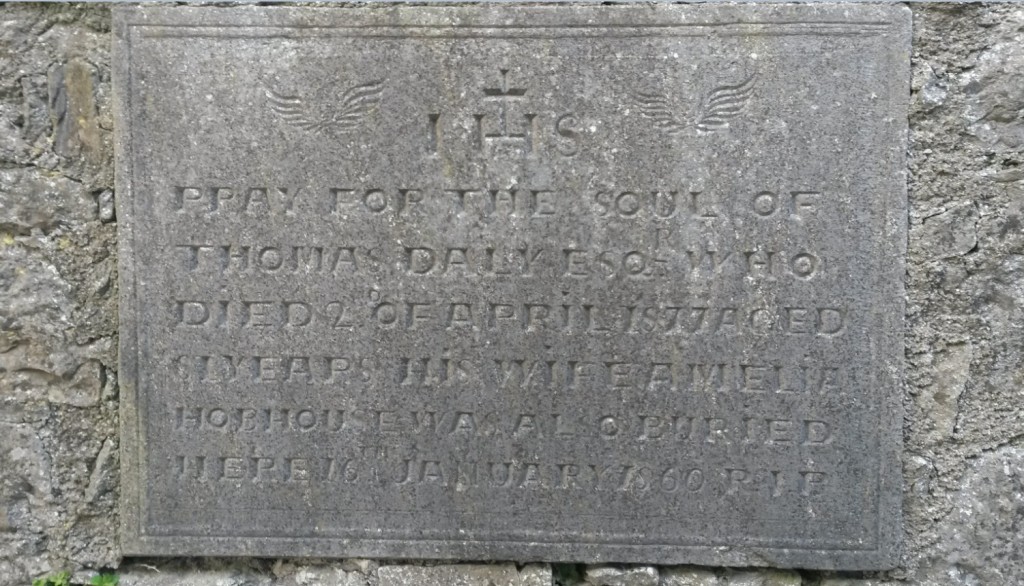

On a mural tablet below that of Lt. Col. Dermot Daly and Major Teige O Daly:- ‘Pray for the soul of Thomas Daly Esqr who died 2 of April 1877, aged 81 years. His wife Amelia Hobhouse was also buried here 16th January 1860. R.I.P.’

This Thomas Daly was second son of Dominick Daly of Galway by his wife Joanna Harriet Blake who was son of Malachy Daly of Benmore, County Galway. On 13th November 1841 Thomas Anthony Daly married Amelia, daughter of Sir Benjamin Hobhouse, baronet. The wedding took place in Dover and as the groom was a Roman Catholic, the wedding was conducted according to the rites of the Roman Catholic Church and the rites of the Church of England. Amelia Daly alias Hobhouse died at Holles Street in Dublin. In contemporary obituaries relating to the death of his wife in 1860 Thomas Daly was given as resident at Prospect Hill, Galway. The obituary of Thomas A. Daly, Esq., given in the Galway Vindicator newspaper, described his death seventeen years later as having occurred at Averard, near Galway City, ‘where he had been residing for some time for the benefit of his health’. He was given therein as ‘son of the late Dominick Daly Esq., Mount Pleasant, Loughrea and brother of the late Sir Dominick Daly, one of our ablest colonial governors’. The senior-most representative of the Benmore branch of the Daly family in the mid nineteenth century was Thomas’ elder brother Malachy, a banker in Paris in the 1840s. In 1865, not long after returning to Italy from Constantinople, where he had served for a time as private secretary to Sir Henry Lytton Bulwer, Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Malachy Daly died aged 79 years while bathing at Porto d’Anzio. He was described in his obituary in ‘The Gentleman’s Magazine’ as descended ‘of an old Roman Catholic family of County Galway’ and ‘greatly respected and esteemed by the English and Irish Catholic colony in Rome.’ Their youngest brother Sir Dominick Daly, who died in Adelaide in South Australia in 1868, served for a time as Provincial Secretary of Lower Canada, as Lieutenant Governor of Tobago, as Lieutenant Governor of Prince Edward Island and finally, from 1861 until his death, as Governor of South Australia.

‘This Monument was erected by Christopher Alexander and Edward Bytagh for the use of themselves and their posteritie Ano Do 1685’.

An armorial stone bearing a crude depiction of the arms and motto of the Daly family.

Although crude in nature it may date from the late seventeenth or eighteenth century as dateable examples of stones bearing similarly primitive armorial carving may be found in east Galway.

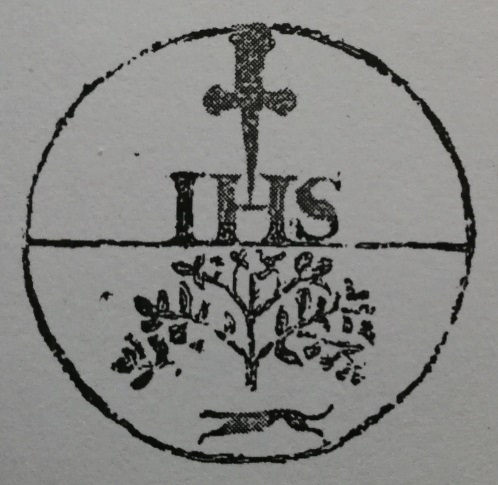

On a stone lying flat in the chancel:- ‘O Lord have mercy on the Soul of Peter Daly, Esq., of Cloncha, Depd this life 11th July 1845, to whose memory this was erected by his wife, Fanny A. J. Daly’.[x] Atop this inscription, in the upper half of a large roundel a cross atop IHS and in the lower half what appears to represent a dog running beneath a bush or tree. The depiction in the lower section of this roundel is clearly intended as the crest of the same Daly family.

Detail taken from a rubbing by F. J. Biggar of the Daly of Cloncha stone, showing the dog courant and tree of the Daly crest. (JGAHS, Vol. I, 1901, p. 165.)

This branch of the Daly family were seated at Clooncah in the parish of Killimordaly in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Lewis in his Topographical Dictionary of 1837 gives Clooncah as the seat of P. Daly. In 1854 the Cloncha estate of Philip Daly was offered for sale in the Encumbered estates Court.

Biggar described this O Daly tomb in the north wall of the chancel as being ‘altar-shaped with a rich canopy of quite different design (to that located at the west door), consisting of a rose tracery on a circular arch, the panels in front being plain’. There was no inscription upon the tomb but the modern O Daly white marble slab (commemorating members of the Daly family of Raford) inserted into the wall above the altar stone he noted ‘does not add to its beauty.’ The architectural features of this tomb would suggest a construction date sometime about the mid fifteenth century. A black and white photograph of this tomb taken by the American Professor Edwin C. Rae in the mid twentieth century survives in the Edwin Rae collection at Trinity College Dublin and shows the presence of a box-tomb to the left of this wall-tomb and adjoining it, protruding at right angles from the wall-tomb into the body of the choir. This box-tomb was no longer in place by the early twenty-first century.

Located to the immediate east of the Daly tomb, this unidentified tomb, Biggar described as ‘another altar-like niche on the north wall close to the east end quite uninscribed that I can find out nothing about.’ Biggar conjectured that it may have been ‘a sedilia’ ‘as it was quite close to the altar’. Although this altar stone is low, given that sedilia, or in its singular form, a ‘sedile’, would normally be constructed on the south wall of the choir, this niche is undoubtedly a tomb. Similar such tombs, whose features suggest a possible construction date in the fifteenth century, may be found in the friaries of Ennis or Quin in County Clare, Adare, County Limerick or Lislaughtin in County Kerry. Erected in such close proximity to the high altar, this would have been a particularly high status burial site of an important individual or family.

In June 1715 Hugh Kelly of Ballyglas, County Roscommon, regarded as the last in the male line of the Kelly family of Aughrim, transferred ownership of his ancestral tomb or burial place in Kilconnell friary church to his relative Charles Daly of Calla, Co. Galway. The eldest son and heir of Tadhg O Kelly, sometime of Aughrim, Hugh of Ballyglas described the ancestral tomb as having been built by ‘Hugh O Kelly alias Hugh na Gallagh’. Rather than a reference to the Kellys of Gallagh, an alternate line of the name, this may have been a reference to Aedh or Hugh na coille (ie. ‘of the wood’), an ancestor of the Kellys of Aughrim, who attained the chieftaincy of Ui Maine and was killed in 1469. In the deed of transfer, dated 6th June 1715, the burial place was described as located ‘between the tomb, grave or burial place of the same Charles Daly and the high altar in the same convent or monastery, at the Gospel corner of the same altar. It is unclear if it is a wall tomb or simply a grave to which the deed refers. If a tomb it is unclear to which tomb; the wall tomb known as the Daly tomb, to which was later affixed the memorial to the Dalys of Raford or the unidentified tomb, considered by Biggar to be more akin to a sedile. The architectural features of the canopy of either could comply with a date corresponding to the lifetime of Hugh na coille, particularly so the former.

Biggar noted the presence in 1901 of a stone near the north wall of the chancel bearing the inscription in raised latters:- ‘ORATE-PRO-ANIMABUS-THOMAE-HUGONIS-MANNIN-IONNIS- MALACHIAE-MANNIN-GULLIELMI-HUGNOIS-MANNIN-OMNIUM-DE-MINLOGH-QUI-HOC-SEPULCHRUM-SIBI-ET-SUIS-FIERI-FECERUNT-ANNO DNI-1648’.

A simple altar tomb on the south wall of the chancel, known as the O Kelly tomb. On the base facing stone below the altar is inscribed the words:-‘Eleven generations of the Clooncannon family interred here to 1823’. Upon the rectangular altar stone, in descreasing lines about its edge is inscribed the words:-‘Here-under lyeth the bodies of Donagh Grane O Kelly Doniell O Kel. Shane O Kel. and Fardoragh O Kel. desended from Shane O Kelly who caused this ingription to by done for him and his pos.’ In later lettering at the centre of this dedication is inscribed the words:-‘Built 1512 Now Inlarged by Wm Kelly Cloncanon 1823’.[xi]

The modern townland of Clooncannon Kelly lies in the parish of Ahascragh. William Kelly who had the words inscribed on this tomb in 1823 would appear to have been a younger son of Michael Kelly of Clooncannon, who died in 1782, leaving five sons and seven daughters. By Michael’s will of June 1782 the estate passed in trust to William’s elder brother Ferdinand to possess for the duration of his life and to pass then to his heirs male lawfully begotten and in the absence of those male heirs to his next brother William and so on in remainder in like manner in the absence of male heirs to their other brothers. As Ferdinand died in October 1791 without male issue, William would appear to have been next in line to inherit by virtue of that will. William was abroad, however, in 1791 and Ferdinand’s only two young daughters by his wife Mary Walsh; Rose and Maryanne, entered into possession of the house and estate of Clooncannon. On Michael’s return in the following year he brought a case of ejectment against his nieces, who based their defence upon an earlier May 1782 will made by their grandfather William Kelly. When the jury disagreed about the outcome in 1793, the judge recommended the arbitration of mutual friends to decide the matter amicably and the agreement reached in 1794 saw the lands of Clooncannon relinquished to William Kelly. A legal dispute continued however into the following century involving William’s sons Michael and John, William’s niece Rose, married to Charles Lennon and others.[xii]

Rev. Maffett recorded the following inscription in the early 1890s from a flat stone, its upper corner broken, in the centre of the chancel:-‘…the Bodies…Michael Kelly of Girran Esq who Died the 2 day of Iune 1701 Aged 63 Years and his Wife Margaret Kelly alias Daly and his brother Anthony Kelly for them and their Posterity’.

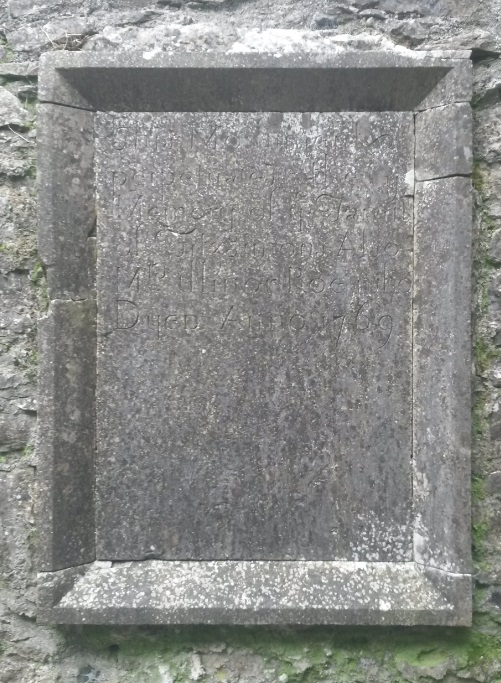

The same source recorded the following inscription on a flat stone in the choir:-‘IHS Pray for the Soul of Mr. Edward Kelly of Cloones….Co. Roscommon, who departed this life ye 22 Day of February 1769 Agd. 62 years. This monument was erected by his family. R.I.P.’

Rev. R. S. Maffatt recorded in the late nineteenth century the memorial on the south wall of the choir bearing the inscription:-‘Sacred to the memory of Joseph Page died August 2nd 1850 aged 80 years. R.I.P.’ Given that Page is an uncommon surname locally and the date of death, this is likely to have been the same Joseph Page mentioned by John O Donovan in his 1838 Ordnance Survey Letters. O Donovan stated then that ‘Joe Page of Moin na mbrather has in his possession a wooden statue of St. Francis which belonged to this abbey’. He would also appear to have been the same Mr. Page of Moin na mbrather to whom O Donovan made reference in the same source as having found the bell of this abbey in the bog of Moin na mbrather a few years prior to O Donovan’s visit. Despite the short time interval, O Donovan stated that the bell was no longer in existence in 1838. It weighted twelve stone, he said, and noted the tradition that it was reputed to have been the loudest bell in Connacht. When F. J. Bigger visited the friary ruins about 1901 he was unable to trace the whereabouts of this bell or the effigy of St. Francis. He had not given up hope of success, however, ‘with the assistance of some local enthusiast.’ He also noted the local tradition then current that the bell was still buried in the same bog.

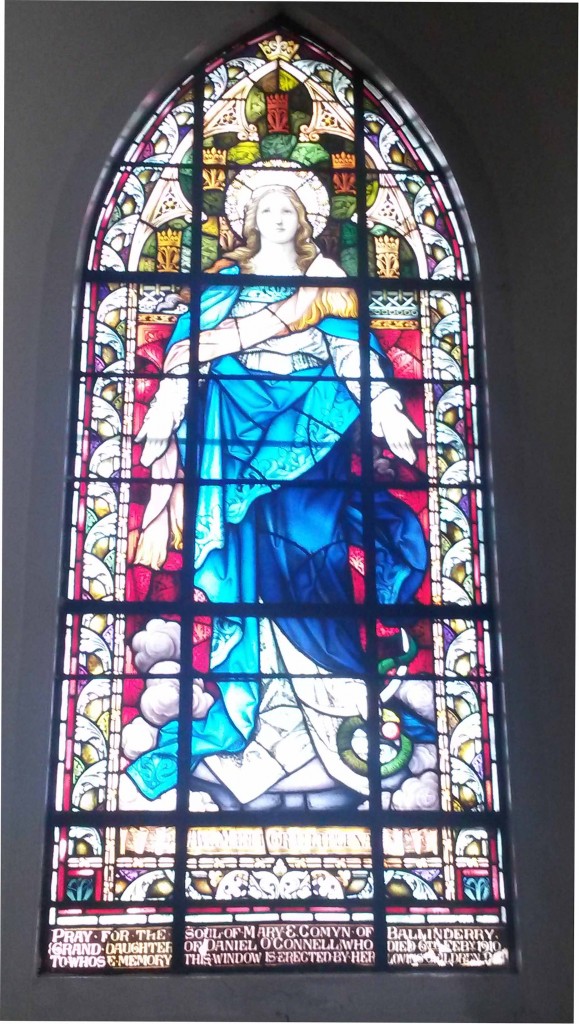

The Ward of Ballymacward armorial stone at Kilconnell friary, incorporated into a later memorial to the Comyn family. Representatives of a family of Sodhan origin in east Galway, the Ward or Mac an bhaird family, with a small kin-group of others such as the O Mannions, Dugans and Scarrys, are held by tradition to have been established in that region prior to the arrival or rise of the O Kellys and the Uí Maine family group. Andrew Comyn of Ryefield, Elphin, County Roscommon married Sabina Ward, sister and heiress of Lewis Ward of Ballymacward and Ballinderry House, Kilconnell in County Galway in 1786 and through this marriage the Comyn family came to be established in the east of County Galway in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century. The armorial stone was evidently incorporated in the Comyn monument by John Ward Comyn of Ballinderry who died in 1929 at the age of ninety-three years. In addition to Andrew Nugent Comyn and his wife and brother, other members commemorated later in an inscription at the base of the stone were Nicholas O Connell Comyn, his son Reginald and Mary Cecilia, wife of the former.

This stone in Kilconnell appears to be the only surviving evidence of the complete achievement of arms of the Ward family of County Galway. As no markings appear on the stone to indicate colour, the stone makes clear the composition but not the original tinctures used on the crest or shield. There is no evidence of a member of this particular family surnamed Ward having their arms recorded in the records of Ulster King of Arms or in those of his successor the Chief Herald of Ireland prior to the second decade of the twenty-first century. The Comyn family utilised a different coat of arms but no record of those arms were recorded in the office of Ulster King of Arms or that of the Chief Herald’s prior to the twentieth century. It was only in 1959 that the Comyn arms were confirmed by Gerard Slevin, Chief Herald of Ireland, as those by right appertaining to Major John Andrew Comyn of Springmount, Mallow, County Cork, grandson of Andrew Nugent Comyn of Ballinderry, Kilconnell, County Galway and Ryehill in County Roscommon, the applicant’s descendants and the descendants of Andrew Comyn of Ryefield.

For further details on the Ward of Ballymacward and Comyn families refer to ‘Heraldry’.

The stained glass window commemorating the death of Mary Comyn of Ballinderry, emphasising her descent as granddaughter of Daniel O Connell. The window was erected by her children in the Roman Catholic church at Kilconnell village, where the family occupied the front pews during their time at Ballinderry.[xiii]

Detail taken from a rubbing of the stone commemorating Michael Ward, Esq., his wife and son, exhibiting the Ward crest and motto found also on the armorial stone incorporated into the later Comyn memorial. (JGAHS, Vol. I, 1901, p. 166.)

On a stone lying flat under the tower;- ‘IHS INRI Lord have mercy on the soul of Michl. Ward Esqr. d.d. 1804 aged 58 Also his wife Margret Ward alias O Daniel, d.d. 1809, aged 54, their son Joseph Ward, Esqr. d.d. 18 March 1818, Aged 42.’[xiv] F. J. Biggar produced a rubbing of the decorated top of this slab which shows in two circular panels either side of a cross fitchee the motto ‘honor virtutis premium’ and on the other a sinister arm embowed, possibly emanating from a curtain or cloud, its hand clasping a short sword. This crest and motto appears again nearby in the choir on an armorial stone incorporated later into a memorial to the Comyn family of Ballinderry and serve to confirm the arms on the Comyn memorial as those of Ward.[xv]

Ribwork to underside of tower

The impaled arms of a Kelly armiger at Kilconnell Abbey, which appears to relate to one Bryan Kelly of Cregan and his wife Susanna Kelly alias Moore. (Vigors, Col. P.D., French, Rev. J.F.M. (eds.), Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead, Ireland, 1892, Vol. II, No. I, pp. 120-121.) Although crudely carved, the treatment of the lions rampant is similar to that employed in a number of other carved armorial stones of east Galway dating from the eighteenth century, such as that of a Lorcan armiger at Meelick and that of an Eyre at Cloonkea in the parish of Clonfert.

It is possible that the earliest surviving example in the east of County Galway of the Moore family of Cloghan Castle in Lusmagh, Kings County, Cloonbigney and Clooncoran, County Roscommon occurs on this armorial stone. The crudely carved stone commemorates an armiger of the Kelly family and stands against the southern wall in the grounds of the choir of the abbey. The elements of the composition stand in high relief from the stone itself with no clear outline of a shield other than that suggested by a scroll-like decorative element extending down from the crest to the base of what is intended as the shield. The arms given here are impaled arms, with a clear strong vertical line in relief dividing the dexter and sinister sides, the Kelly arms given on the dexter side. The arms of the armiger’s wife’s family is depicted on the sinister side, dominated by a lion rampant over what are a pair of barely-discernible incised horizontal lines in chief behind.

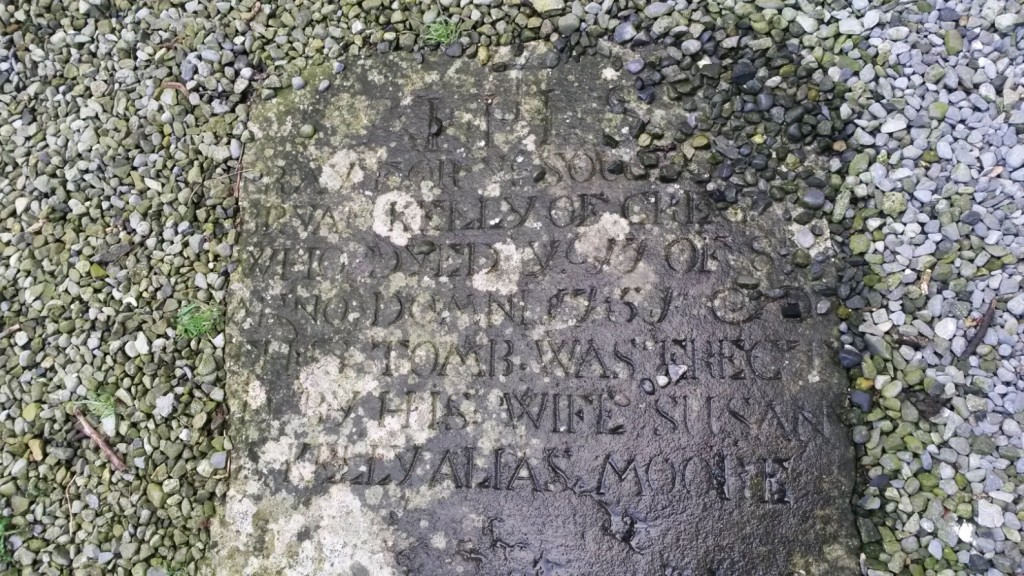

No inscription was provided on this stone but Rev. R.S. Maffett visited the abbey at Kilconnell in the late nineteenth century and noted in 1892 an inscription on a flat stone at the foot of the armorial stone; ‘IHS, Pray for ye Soul of Bryan Kelly of Grigan who died ye 17 of 8 Anno Domini 1751. This stone was erected by his wife Susanna Kelly alias Moore.’ It would appear likely that the armorial stone may be that of this Bryan Kelly with the arms on the sinister side a primitive representation of the Moore arms, the incised twin horizontal lines behind the lion’s head intended to represent the bars Sable associated with the Moores of Barmeath from whom the family of Cloghan castle, Cloonbigny and Clooncoran descend. The lion rampant Gules upon the bars was associated with this latter family.

This stone commemorating Bryan Kelly and his wife may have been difficult to decipher accurately on the occasion of Rev. Maffett’s visit and reads more correctly ‘Bryan Kelly of Cregan’. The Kelly armiger in this case would appear to have been a representative of the Kelly family of Creggaun House in the parish of Ahascragh, whose lands lay in the barony of Clonmacnowen, north of the town of Ballinasloe and within a short distance across the River Suck of the property of the Moores at Cloonbigny and Clooncoran. The property of this Kelly family, containing a house and demesne of over three hundred acres was advertised for letting in March of 1826, following the death of Hugh Kelly, Esq., who left no family.[xvi]

The inscribed flat stone whose inscription was noted by Maffett is still located within the body of the chancel but the heraldic stone, located against the wall of the chancel, is at a short distance from the flat stone. As it is positioned on axis with the 1751 stone, it is uncertain if it was originally in this position when recorded by Maffett or if the stone was originally immediately ‘at the foot’ of the armorial stone as described by him.

On a mural slab in the south wall of the chancel:- ‘IHS pray for ye soul of James Waldron, who d.d. 1762 Errectd by his wife Mary Waldron’.

IHS This monument was erected by Maddin Burke for his wife Frances Burke alias Donelan who dyed the 19 March 1753 for them & their posterity and the Lord have mercy upon their souls. 1734[xvii]

II

Memorials within aisle, transept, Donnellan chapel and ancillary rooms

An armorial stone tablet set in the wall of the small sacristy on the north side of choir in Kilconnell friary reads ‘Here lies the body of Mathias Barnewall the 12 Lord Barron of Trimlestowne who being transplanted into Conaght with others by orders of the usurper Cromwell dyed at Monivae the 17 September 1667 for whom this monument was made by his sonne Robert Barnewall the 13 Lord of Trimlestowne. Here lyeth alsoe his unckle Richard Barnewall James Barnewall whoe dyed at Cregan the 2 October 1679 and James Barnewall of Aghrim. God have mercy on theire soules.’

On a mural tablet to the right hand side of the Barnewall memorial in the sacristy, the following inscription:-‘This monument perpetuates the Memory of ye Family of Fitzsimons. Also Mrs. Ellinor Roe who Dyed Anno 1769′.

A Fitzsimons family were seated at Carrownea, in the parish of Ballymacward, to the north-west of Kilconnell, in the early nineteenth century. Near that house, in the adjacent townland of Carrownea Upper, was located a small circular burial ground that, at the end of the nineteenth century, was used as a burial place for unbaptised children. Children were still being interred there in 1902. While the burial ground was unenclosed in that year, with cattle grazing across the land, F.J. Biggar and Herbert Hughes reported that it had previously been enclosed and noted the presence on their visit of a small upright slab beside an aged thorn bush at the centre of the burial ground bearing the inscription:-‘Mr. Fitzsimons has enclosed this small berual place AD 1838′.[xviii]

On a mural tablet in the east wall of the small sacristy on the north side of the choir:- ‘This monument was erected by Michael Cvnnfe & his wife Margret Nolane Lavrence Cvnnfe & his wife Elizabith Ke__b_others for them & their posterity 1753 & the Lord have mercy vpon their sovles’.

On a ruined tomb in the transept, Biggar noted the following inscription in 1901:- ‘Pray for the soul of Michael Dalton of Raara, Esq., who died 28th of January 1752’. Round the edge of the stone he noted what he described as evidently a portion of the monument erected by Boetius Egan, as noted above.

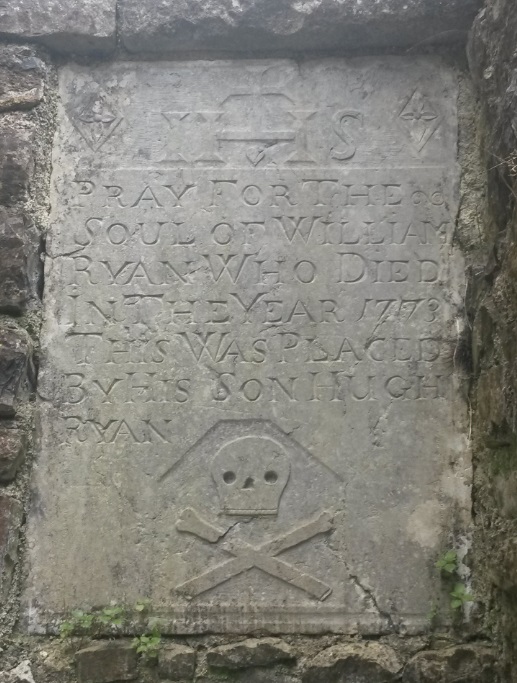

A stone placed at high level in the cloister passage to the tower:-‘IHS Pray For The Soul of William Ryan Who Died In The Year 1773 This Was Placed By His Son Hugh Ryan’. Beneath the inscription a primitively carved skull and crossed bones.

On a vertical stone in the cloister passage to the tower:- below a crest on a wreath of an arm in armour embowed, without gauntlet or glove, holding a short sword beneath the motto ‘vincam vel moriar’ the inscription ‘Here rest the remains of the Stanfords of Balindery & B.glass This Enclosure was erected by the only Surviving member Captain Francis Stanford AD 1849′.

On the wall of the cloister ambulatory, to the right of the door to the tower stair, a mural slab with the inscription:-‘Sacred to the memory of Anne Hozier of this parish who departed this Life the 13th day of February 1844 aged 84 years. Having survived her beloved husband Thomas Michael Hozier, Solicitor, 51 years. R.I.P. This tablet was erected by their affectionate son and only child James Hozier of London’. The stone bears the suppliers details ‘Denham, 83 Regent St., London’.

On the west wall of the south aisle, a limestone mural memorial bearing the inscription:-‘In Loving Memory of John Callanan who died March 25th 1874 aged 52 And His Wife Margaret M. Callanan who died Dec. 15th 1902 Aged 70 years. Ellen Callanan died May 10 1908 Aged 86 yrs and Mary Callanan nee Fahy who died June 27th 1910 aged 32 years’ and on the same memorial at lower level:-‘Joseph Callanan died October 18th 1836 aged 64 years Marjorie Callanan died July 1st 1940 aged 21 years Kathleen Josephine Callanan nee Keary died 25th September 1957 aged 78 yrs William Callanan died 7th August 1969 Alice Callanan died 23rd December 1988 P. Callanan R.I.P. died 19. 3. 1990’.

An inquisition of 1616 noted the existence of a chapel called ‘Tawhell Donellans Chapell’ among the buildings of the friary. Rev. Meehan mentioned in 1869 the local tradition still then current ‘that O Donnellan of Ballydonnellan built a portion of the church and monastery’. It is certain, he noted, ‘that Tully O Donnellan in 1412 erected the mortuary chapel which to this day (ie. 1869) is called Chapel-Tully’. Kilconnell, he noted, was still at that time the burial place of the O Donnellans.[xix] The Donelan chapel is taken to be that small structure accessed from the south transept, containing a memorial to James Donelan, who died in 1701. Biggar noted in 1901 that this was only O Donnellan tomb then to be found and, situated on the north wall of this chapel, bore the following inscription, in raised letters:-‘Hic iacet. D-iacob donnellan, s-t. aci. can. doctor. obit 29 8bris. 1701. in cuius. memoriam. hoc. monumnetum. erectum. fuit. ab. illustrisimo. do. do. Mauritio. Donelan. e. clune, an. do. 1705. pro suo. etiam. monument.’ Since that date two stones were laid about the centre of that chapel, one of which reads ‘The Donelans of Ballydonellan Castle and Killagh House Rest in Peace’ and the other ‘IHS Stephen Joseph Donelan, Killagh, whose remains are buried beneath this stone.’

[i] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell in the County of Galway, JGAHS, Vol. 2, 1902, pp. 3-20. ‘Ms. notes of a visit to Kilconnell by Sir Thomas Molyneux, Bart., in 1709, preserved in Trinity College Dublin, Class 1, Tab. 4, No. 12 and published in the Miscellany of the Irish Archaeological Society, Vol. 1, Dublin, 1846’ and footnote, p. 11.

[ii] The Family and Estate Papers of the Eyre Family of Eyreville, in possession of the author.

[iii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 25-0-39/JOD/168.

[iv] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell in the County of Galway, JGAHS, Vol. I, 1901, pp. 145-167.

[v] Jennings, B., The Abbey of Kilconnell: Two Documents, JGAHS, Vol. 21, No. 3/4 , 1945, pp. 184-189.

[vi] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell in the County of Galway, JGAHS, Vol. 2, 1902, pp. 3-20.

[vii] Jennings, B., The Abbey of Kilconnell: Two Documents, JGAHS, Vol. 21, No. 3/4 , 1945, pp. 184-189.

[viii] Examples of tombs commissioned in the early or mid seventeenth century in east Galway may be found in the MacJonack Burke tomb at Kilnalahan or the hannin tomb at Abbeygormacan.

[ix] Jennings, B., The Abbey of Kilconnell: Two Documents, JGAHS, Vol. 21, No. 3/4 , 1945, pp. 184-189. An abstract of the 1728 will of Edmond Kelly, barrister, sometime Attorney General of Jamaica, who purchased the Lisduff estate in 1716 and who died in March 1727/28, suggests that this Mary Hamilton alias Kelly of Lisduff was aunt of this Edmond and wife of Darcy Hamilton of Fahy, County Galway. The Pedigree of the Hamilton family of Manor Eliston and Fahy 1591-1767 in G.O. Ms. 165 (formerly part of the records of Ulster King of Arms) suggests that Darcy Hamilton may have been twice married, he being given therein as married to Catherine, daughter of Robert French of Rahassane, Co. Galway.

[x] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell in the County of Galway, JGAHS, Vol. I, 1901, pp. 145-167.

[xi] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell in the County of Galway, JGAHS, Vol. I, 1901, pp. 145-167.

[xii] Irish Equity Reports of Cases (during the years 1844 and 1845), Vol. VII, Dublin, Hodges & Smith, 1845, pp. 98-113.

[xiii] Nolan, L., The Past Recalled, Scannell, J and Cooke, C. (eds.), The Social History of Aughrim since 1691, Aughrim Development Co. Ltd., 2004, pp. 158-163.

[xiv] Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead in Ireland, Vol. II, Part II, being the years 1892-93-94, Peter Roe, Dublin, 1895, pp. 118-127.

[xv] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell in the County of Galway, JGAHS, Vol. I, 1901, pp. 145-167.

[xvi] Dublin Evening Post, 23 March 1826. Creggaun, given as ‘Cregane’ was described as situated one mile from Ballinasloe by a foot-way and three miles by the high-road; within three miles of Ahascragh and ten of Athlone. The house was described in March 1826 as ‘a commodious dwelling house, the greater part of which is new and slated.’

[xvii] Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead in Ireland, Vol. II, Part I, being the years 1892-93-94, Peter Roe, Dublin, 1895, pp. 118-127.

[xviii] Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead in Ireland, Vol. V, No. II, Part I, being the year 1902, C.W. Gibbs & Son, Dublin, 1903, p. 216.

[xix] Jennings, B., The Abbey of Kilconnell: Two Documents, JGAHS, Vol. 21, No. 3/4 , 1945, p. 186; Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell in the County of Galway, JGAHS, Vol. 2, 1902, p.11.