© Donal G. Burke 2015

Edward MacLysaght, in his ‘Irish Families, Their Names, Arms and Origins,’ described the name Moran as essentially a Connacht name and held that the majority of the population so called belong to the Connacht counties of Mayo, Galway, Roscommon and Leitrim. This he ascribed to the presence at one time of ‘two quite distinct septs of O Morain and O Moghrain, now both anglicised Moran’ who ‘held their territory in that province. O Morain was a chief in County Mayo and resided near Ballina; O Moghrain, earlier O Mughrain, of Uí Maine, was chief of Criffon in Co. Galway and another was head of a powerful family in Co. Roscommon, seated near Ballintubber.’[i]

The earliest reference to the Uí Mughrain or Uí Muroin of Uí Maine occurs in the Book of Lecan, an early fifteenth century manuscript compiled from earlier manuscripts. They were described therein as one of the three oirrigh (‘under-kings’ or sub-chieftains) over the Síl Crimthainn Cháil or ‘the Race or ‘Seed’ of Crimhthainn Cael,’ alongside the Uí Mailruanaidh (O Mulrooneys) and Uí Chathail (O Cahills).[ii] The Uí Muroin were given as such between the former and latter.

The Síl Crimthainn Cháil

The Síl Crimthainn Cháil were a name applied to a group of related families who formed an offshoot of the wider Uí Maine family group, whose ancestor has traditionally been held to be one Maine Mór, son of Eochaidh feardaghiall, chieftain of a tribe of people who established themselves as the dominant group in the south-eastern region of Connacht by about the end of the fifth century.[iii]

Maine Mór and his descendants appear to have subjugated many of the existing tribes and peoples that inhabited their land and established a petty kingdom, covering much of the later east Galway named from their progenitor as Uí Maine (later Anglicised Hy Many).

In an early account of the duties and services rendered by the various branches and family groups within the wider Uí Maine to the chieftain, the Síl Crimthainn Cháil, together with the Clann Aedhagain, were given as having ‘the headship of every people who revenge the insults of Uí Maine.’ In addition the Síl Crimthainn Cháil or Crumhthann were responsible for the ‘conartha’ or hounds of the chieftain of Uí Maine and ‘the proclamation of his battles.’[iv]

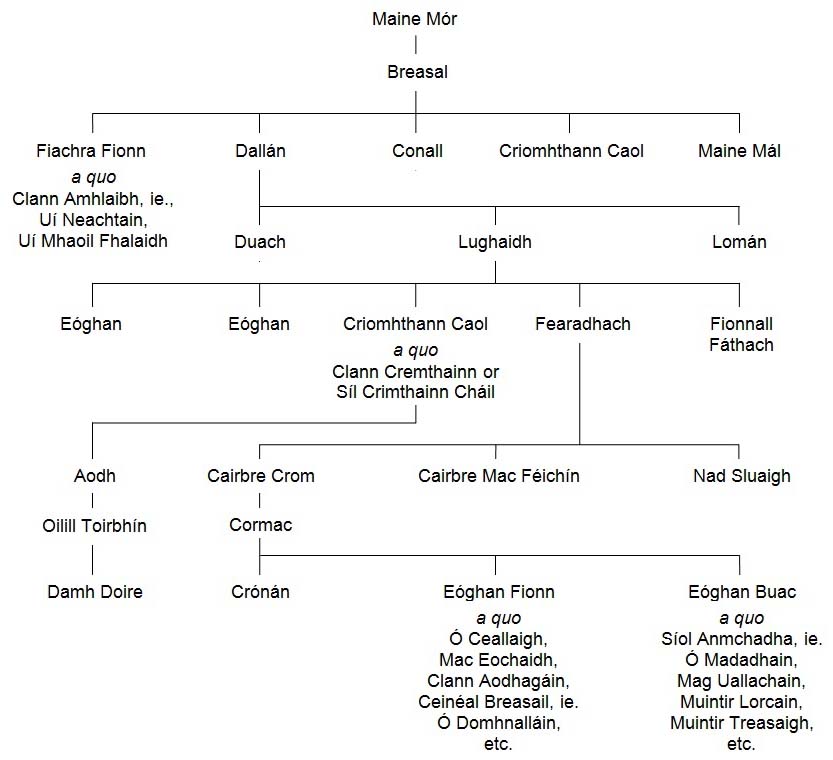

The Síl Crimthainn Cháil would appear to have descended specifically from Crimthann Cael or Caol (ie. Crimthann ‘the slender’), one of the five sons of Lughaidh, son of Dallan son of Breasal son of Maine mór. He appears thus as the ancestor of Sochlachán, who died in 908, an early chieftain of Uí Maine in the Book of Lecan and also in MacFirbisigh’s seventeenth century ‘Great Book of Genealogies,’ where he is given as Criomhthann Caol. An earlier Crimthann Cael also appears in the pedigrees of the Uí Maine (including that given by MacFirbisigh) as an uncle of Lughaidh son of Dallán and younger son of Breasal son of Maine Mór and the nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan gave that Crimthann Cael as the ancestor of the Síl Crimthainn Cháil in his ‘Tribes and Customs of Hy Many.’[v]

Pedigree table showing prominent early members of the Uí Maine, as given by MacFirbisigh in his ‘Great Book of Irish Genealogies.’

There is no evidence to suggest that Crimthainn Cael attained the chieftaincy of Uí Maine, but an early fourteenth century poem addressed to Eoghan O Madden listed among the early chieftains of Uí Maine Crimthainn Caels’ father Lughaidh, his uncle Duach, his grandfather Dallán and his grandfather’s brothers, great-grandfather and great-grandfather.[vi] According to the same poem Lughaidh’s son Feradhach succeeded to the chieftaincy. He was killed by one Marcan who thereby attained the chieftaincy but who in turn was slain and the chieftaincy thereafter attained by Cairbre Crom, son of Feradhach. After ruling for nine years about the mid sixth century, Cairbre Crom was reputedly killed by his brother Cairbre Mac Feichine, who then became chieftain.[vii] Cairbre Mac Feichine was said to have ruled for twenty six years before he was killed by Crimthainn. The identity of this Crimhthainn is uncertain but may have been Crimthainn Cael given that he was uncle of both Cairbre Crom and Mac Feichine. Crimthainn did not, however, attain the chieftaincy thereafter but rather Cormac son of Cairbre Crom. The poem addressed to Eoghan O Madden was incomplete in its list of chieftains and considered by John O Donovan to be imperfect ‘but valuable in preserving the names of several chiefs of this territory not to be found in any other authority.’[viii]

There is no evidence to suggest that any descendants of Crimthainn Cael attained the chieftaincy in the immediate generations following his death, with that office held for much of that time by various descendants of his brother Feradhach. However, a number of representatives of this family group descended from Crimthann Cael did provide chieftains over the entire territory of Uí Maine about the latter years of the ninth and early tenth century. (O Donovan confined the number of descendants of Crimthainn Cael who served as chieftains of Uí Maine to three.)[ix] Sochlachán, who served as chieftain of Uí Maine about the end of the ninth century, died as a priest in 908.[x] It is taken that he resigned the chieftaincy several years prior to his death as his son Mughron held the chieftaincy of Uí Maine in the early years of the tenth century and died in 904 as chieftain of Uí Maine in his father’s lifetime. The Annals of the Four Masters recorded for that year that ‘Mughroin mac Sochlachain, tighearna Ua Maine, d’ég,’ or Mughroin son of Sochlachan, lord of Uí Maine, died. The same annals recorded the death of his father four years later; ‘Sochlachán mac Diarmada, tighearna Ua Maine, d’ég h-i c-cleircecht (ie. in the clerical state).’

Mughron’s brother Murchadan or Murchatan acquired the chieftaincy and appears to have succeeded Mughron.[xi] He died as chieftain of Uí Maine in 936, the Annals of the Four Masters describing him at his death as ‘Murchadh mac Sochlacháin.’ Murchadan was given in the Book of Lecan and by MacFirbisigh as the senior-most representative of the Clann Cremthainn or ‘family or sons of Cremthann’ and his descent given as son of Sochlachán son of Diarmuid son of Fearghus son of Murchadh son of Dubh Dhá Thuath son of Daimhín son of Damh Doire son of Oilill Toirbhín son of Aodh son of Criomthann Caol one of the five sons of Lughaidh one of the three sons of Dallán son of Breasal son of Maine Mór.[xii] (The Book of Lecan, however, gave Damh Doire as son of Ailell son of Coirbin son of Aodh).

Dominance of the descendants of Ceallach

The Síl Crimthainn Cháil were eclipsed by the middle of the tenth century by the senior-most members of the family group reputedly descended from Cairbre Crom. If the first representative of the Síl Crimthainn Cháil to be chieftain was Sochlachán and if the fourteenth century poem addressed to Eoghan O Madden was correct, by implication, therefore, the acquisition of the office of chieftain by members of the Síl Crimthainn Cháil was an aberration rather than the natural order, given that both distinct branches, descendants of Crimthann Cael and those of his nephew Cairbre Crom, were separated by approximately ten generations by the lifetime of Sochlachán. However, as neither Sochlachán or his two sons were mentioned in the fourteenth century poem, it is possible that earlier members descended from Crimthainn Cael may have held the chieftaincy at various times but no record of such survived.

From Cairbre Crom descended many of who would later become the most prominent of the Uí Maine families such as the O Maddens, O Donnellans, MacCuolahans, O Treacys, O Lorcans, O Coffeys and others. Politically the senior-most family descended from Cairbre Crom would prove to be the O Kellys, from whom the later rulers or chieftains of Uí Maine were drawn.

The O Kellys of eastern Connacht claim derive their name from one Ceallach, said to have been fourteenth in descent from Maine Mór. (The nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan was of the view that this Ceallach may have flourished in the mid ninth century and died about 874, basing his calculation on the fact that one Cathal MacOilioll (‘son of Ailill or Oilill’) chieftain of Uí Maine died in 844 and this Cathal was given as being a generation earlier in descent from Maine Mór in pedigrees.) It is unclear if Ceallach ever held the chieftaincy of the territory as Cathal son of Oilill was mentioned as chieftain in 834 at which time he plundered the religious foundation at Clonmacnoise and defeated the Irish king of Munster, while, as O Donovan observed, no mention was made of Ceallach in Irish Annals.[xiii]

Ceallach’s grandson Murchadh, son of Aedh son of Ceallach is believed to have succeeded to the chieftaincy of Uí Maine after the death in 936 of the chieftain Murchadhan son of Sodhlachán, of the Síl Crimthann Cael. At his death in the year 960 he is referred to as ‘Murchadh son of Aedh, Lord of Hy Many in Connacht.’[xiv] Murchadhan’s brother Geibheannach was chieftain at his death in 971.[xv] Thereafter the senior-most descendants of Ceallach, who came to be known from their common ancestor as O Kellys, appear to have maintained for much of the time the ascendancy among the other family branches in the kin group.

Chieftains of Creamthainn or Cruffon

O Donovan described the Síl Crimthann Cael or ‘Cruffons’ as having ‘sunk at an early period.’[xvi] The three senior-most families ruling over the group were given in the Book of Lecan as the Uí Mailruanaidh, Uí Muroin and Uí Chathail, described as sub-chieftains over that group of families under the chieftain of Uí Maine. This was repeated by the Gaelic poet and historian John O Dugan, who died in 1372, in his topographical poem in which he wrote;

‘O Cathail, O Mudhroin mear / O Maolruanaidh na ríghfhleadh / Croind díona an ur-fhuinn eanaigh / Ríogha Crumhthainn crichfheadhaigh…’[xvii]

‘O Cahill, O Muroin the swift, / O Mulrooney of the royal feasts / sheltering trees of the rich boggy land / kings of Crumhthann, wooded district…’

The poem is believed to relate to a period prior to the late twelfth century as it refers to O Mulally or Lally and O Naughton as lords of the territory of Maenmagh about Loughrea, from which they were dislodged, possibly in the time of Conchobar maenmhaighe O Conchobhair or O Connor, who died in 1189.[xviii] Of these three it would appear that the Uí Mailruanaidh were the most prominent in the late tenth and early eleventh century and were described as lords or chieftains of a region which derived its name from the wider family group and came to be known as Creamthainn (anglicised ‘Cruffon’). It would appear therefore that both Uí Morain and Uí Cathail had been eclipsed in that region by the Uí Mailruanaidh at least by the late tenth century.

It is noteworthy, however, that the account in the Book of Lecan naming the three sub-chieftains of Creamthainn stated that two of the three sub-chieftains were of the same race as the Síl Crimthainn Cháil and one of another separate and distinct family group known as the Síol Muireadhaigh. This latter group were of the same stock as the O Connor Kings of Connacht and were not directly related to the Uí Maine families. The tract did not identify which of the three was of the Síol Muireadhaigh and which of the Uí Maine.

The extent of Creamthainn or Cruffon

Denis Henry Kelly of Castle Kelly, in a letter to John O Donovan, described Cruffon in the early nineteenth century as ‘the name by which the peasantry still designate a large district in the county of Galway, long celebrated for its coarse linen manufacture, containing the barony of Killyan and a large tract of Ballymoe.’[xix] The Ordnance Survey Letters of 1839 relating to County Galway described Cruffon in more detail as having extended from ‘Mount Talbot to Mount Bellew and from Creggs to Castleblakeney or Caltragh in the par of Killosolan. It includes the parishes of Killian, Killoran, Ballynakill, Killasolan and part of Athleague.’ Another account described it as having ‘extended from Mount Talbot to Mount Bellew and from Creggs to Castleblakeney. It contained the barony of Killian (less that part of the parish of Taghboy in County Galway) and the parish of Killasolan in Kilconnell barony.’[xx]

Other families who held lands in Creamthainn or Cruffon, other than the Uí Maelruanaidh, Uí Morain and Uí Cathail, appear to have been the MacEgans, with the Clann Aedhagain, together with the ‘Crimthainn,’ having at an early period ‘the headship of every people who revenge the insults of Uí Maine.’ That they held lands in Creamthainn into the medieval period would appear to be confirmed by the account of the lands of the Clann Aedacain being plundered in 1260 in a raid on lands in Cruffon directed by Walter de Burgh, the Anglo-Norman lord of Connacht, during an expedition against Feidhlim Ua Conchobhair. They were, however, descended from Cairbre Crom and therefore of a distinct and separate line of the Uí Maine to that of the Síl Crimthainn Cháil.

Ua Maelruanaidh, Lord of Creamthainn or Cruffon

In the period prior to the general adaption of surnames by the Gaelic Irish, and possibly prior to the period when Sochlachán of the Síl Crimthainn Cháil acquired the chieftaincy of Uí Maine, one of the lords of the district or people known as Creamthainn was given as Cian son of Eochaidh, who died in 867. However, by the latter years of the tenth century, after the accession to power over Uí Maine of the immediate descendants of Ceallach, the lord of Creamthainn was given as Maelseachlainn Ua Maelruanaidh, who was slain by the Uí Ceallaigh in 998 or 999.

The Annals of the Four Masters, in describing the killing in 1029 of Brian ua Conchobhair, ‘Ríoghdhamhna Connacht’ (ie. ‘one eligible to attain the kingship of Connacht’) by the lord of Creamthainn identified the latter as Maolsechlainn mac Maol Ruanaidh, ‘tighearna Crumhthann’ or ‘lord of Creamhthainn.’ Although he was called therein ‘mac Maol Ruanaidh’ or ‘son of Maol Ruanaidh,’ it would appear that he was more correctly ‘Ua Maol Ruanaidh’ as the same annals mentioned in the following year that ‘Tadhg an Eich Ghil ua Concobhair, rí Connacht, do mharbhadh lasan n-Gott, i. la Maol Sechlainn ua Maol Ruanaidh, tigherna Midhe agus Cremthainne.’ Although the structure of the text would appear to be unclear, it would appear to translate as ‘Tadhg of the white horse Ua Conchobhair, King of Connacht, was killed, together with an Gott, King of Midhe, by Maol Sechlainn Ua Maol Ruanaidh, lord of Creamthainn.’ The death of both individuals was confirmed by both the Annals of Loch Cé and of Ulster, albeit neither source mentioned the individual responsible for the killing.[xxi] It is further confirmed by the killing in 1036 of Maol Sechlainn Ua Maol Ruanaidh, tighearna Cremhthainne, by Aedh Ua Conchobhair in revenge for the deaths of Tadhg an Eich Ghil and Brian Ua Conchobhair.

The position of the senior-most Ua Maelruanaidh as a significant sub-chieftain within Uí Maine in the mid eleventh century is confirmed in an account of a plundering raid made in 1048 into the territory of Dealbhna by the ‘ríghdhamhnibh nó taoiseachaibh h-Ua Máine’ (ie. the ‘princelings’ or ‘leaders’ of Uí Maine), in which all the ‘ríogh-thoisigh’ or ‘royal-leaders’ were killed. Those killed were given as ‘Ua Maol Ruanaidh, Ua Flannacáin, an Cleireach Ua Taidhg and mac Buadhachain, the last given as ríghdhamhna Dealbhna.’[xxii]

Seventeenth century

Despite the dominance within Creamthainn of the Uí Maelruanaidh in the eleventh century, no record of any of the name survived as significant landed proprietors within that district or in east Galway by the early seventeenth century. By that time there was no landed proprietor of the name Moran the possessor of lands within what had been the territory of Creamthainn or Cruffon. The only landed proprietors of the name O Moran did, however, survive in east Galway in the early and mid seventeenth century, near the border of County Galway with that of Mayo, to the north-west of, and at a distance from, Cruffon.

Donnogh, Thomas, Shane and Owin O Mouran of Cloonmore were among the many of County Galway issued a general pardon by the Crown in 1603, the first year of the reign of King James I.[xxiii] Although Cloonmore is a common place-name throughout the county and country, it would appear likely that the Cloonmore in question was the denomination of that name in the parish of Dunmore, given the location of the only landed proprietor of the name in the county within the same parish in the following decade. Cloonmore lay to the west of the lands of the MacEgan castle of Park and to the south-east of the modern village of Dunmore, while the lands of David O Moran lay to the north of Cloonmore, about a hill in the modern townland of Knockaunbrack and to the east of the modern village of Dunmore in the second decade of the seventeenth century.

About 1618 David O Moran of Knockenbracke in Galway County, gentleman, held two thirds of the quarter of Knockenbracke, two thirds of the half quarter of Tuarnamiltoge, and one third of a quarter of Rinclaremore, all in the half barony of Ballymoe.[xxiv]

In 1641 the only landed proprietor of the name Moran in County Galway was Davey Muran holding two thirds of the quarter of ‘Knockanbrae’ (recte: Knockaunbrack) in Dunmore parish. It is unclear if he was the same individual who held the same section of land over twenty years earlier or if he was a close family member.

The O Morans lost possession of their lands in the parish of Dunmore as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century. The land previously owned by Davey Muran or Moran was acquired by others and as a result the only discernible senior line of the name disappeared from the ranks of the landed families of east Galway. In the late 1660s, following the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, Moran’s land at Knockaunbrack formed part of extensive estates acquired by Sir George St. George.[xxv]

[i] MacLysaght, E., Irish Surnames, Their Names, Arms and Origins, Fourth Edition, Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 1985, p. 129.

[ii] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 70-73. ‘Trí h-orra ar Sil Crimthainn Cháil, dá orrig d’á shíl féin ocus orrig do Shil Muireadaigh.’

[iii] Knox, H.T., The Early Tribes of Connaught: part 1, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth series, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1900, p. 349; Mannion, J., The Senchineoil and the Sogain: Differentiating between the Pre-Celtic and early Celtic Tribes of Central East Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 58, 2006, pp. 166, 168; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Leabhar na g-ceart or The Book of Rights, Dublin, M.H. Gill, for the Celtic Society, 1847, p. 106.

[iv] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 89-91.

[v] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 24, 73 footnote e. O Donovan refers to a manuscript preserved in Trinity College Dublin H. 2. 17, p. 49.

[vi] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, 1843, pp. 13-14.

[vii] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, 1843, p. 15. O Donovan gave Cairbre Mac Feichine as ‘ancestor of the tribe called Cinel Feichin, who were seated in the barony of Leitrim, in the south of the county of Galway.’ He gave two of his sons of Brenainn Dall, who died in 597 and Aedh Guaire, relative of St. Rodanus of Lorrha.

[viii] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, 1843, pp. 13-14.

[ix] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, 1843, p. 73. Footnotes e.

[x] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 27. Footnotes f,g.

[xi] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 27. Footnotes f,g.

[xii] Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. II, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp. 45-7; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, 1843, p. 27.

[xiii] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, 1843, p. 97.

[xiv] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 98-99.

[xv] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 98-99.

[xvi] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 98-99.

[xvii] O Donovan, J. (ed.), The Topographical Poems of John O Dubhagain and Giolla na naomh O huidhrin, Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society, Dublin, 1862, pp. 48, 68-71; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 73. Footnote e.

[xviii] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 70-71. Footnotes a, b.

[xix] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 73. Footnote e.

[xx] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839, p. 109; MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. lxi.

[xxi] Annals of Loch Cé, 1030.6; Tadhc an Eich Ghil macCathail mic Conchobhair i. airdrigh Connacht agus an Got, ri Midhe occcisi sunt; Annals of Ulster, 1030.5; Tadhg H Concobhair ri Connacht agus In Got rí Midhe occisi sunt.

[xxii] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, 1048.17.

[xxiii] Cal. Pat. Rolls, 1 James I, p. 19.

[xxiv] Cal. Pat. Rolls, 16 James I, p. 414.

[xxv] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. xiv-xvii, xix, 298.