© Donal G. Burke 2013

A list of selected place-names, some current and some no longer in use, within the barony of Longford in the east of County Galway.

This list will be updated and revised on a regular basis.

Map showing seventeenth century parishes of the Barony of Longford (in yellow), County Galway with modern towns and villages (in red).

Abbeyland Great: Refer to ‘Knockmoydarregg’ below.

Addergoole: a denomination in that part of the parish of Abbeygormacan that lies within the barony of Longford, deriving its name from the topography of the surrounding area. The name is a rendering of the original Irish ‘idir ghabail’, that is, ‘between the fork.’ The ‘gabhal’ or ‘fork’ in this case relates to the fork of a river in the immediate vicinity. In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 two denominations were given; ‘Edrugilbeg’ and ‘Edrugilmore scilicet (‘that is to say’) Ballimakin et Isgirboy’.[i] As the modern Addergoole is a distinct townland separate from the two adjacent modern townlands of Ballyvaheen and Eskerboy in the same parish, it would imply that the modern Addergoole equates to the medieval ‘Edrugilbeg’ or ‘Addergoole beag’ (Addergoole Little) and Edrugilmore or ‘Addergoole mór’ (Addergoole Great or ‘Large’) to the area comprised of Ballyvaheen and Eskerboy.

Annaghcorba: Located west of Clonfert on Petty’s mid-seventeenth century map, on the verge of boggy lands in the parish of Clonfert, this equates to the later townland of Annaghcorrib in the parish of Clonfert, the old name meaning ‘the marsh of the comharba’, comharba being a position indicating the successor to the founder of a religious house. This would appear to be that Annohherbye given as part of the ‘manors, castles and lands’ surrendered by the last chieftain Domhnall O Madden in 1585 and regranted to him under English tenure. Refer also to ‘Cartronaceapanamallagh.’

Ballaghill: This would appear to be the modern townland of Ballycahill, parish of Killimor. Refer to the Treacy family, etc.

Ballineclunty: In the 1585 Indenture of the barony of Longford Balleneclanty was composed of four quarters of land. Much of the four quarters that composed lands identified as Ballineclunty was held by members of the O Mullvihill based at Derrin in the sixteenth year of the reign of King James I.[ii] As the O Mulvihills appear as a minor landholding family in O Maddens country in the late medieval and early modern period, confined to an area in that barony about the townland of Derreen in the parish of Kiltormer, it would appear Ballineclunty was located at, or adjacent to, that denomination.

Ballyhoose: a townland in the former parish of Clonfert. It is noteworthy that in the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 that the denomination is given as ‘Byllecuas’.[iii] The ‘Bally’ in this case may be a corruption of the Irish word ‘bile’, an old tree held to be sacred or venerated. P.W. Joyce was of the opinion that the ‘bally’ of Ballyhoose referred rather to a ‘bile’ or old sacred tree than the alternative reading of ‘baile’, and in Irish may have been ‘Bile Chuais’.[iv] The 1407 version of this placename would support this opinion.

Ballyhugh: Refer to ‘Knockmoydarregg’. Colonel Eyre met with active resistance from several of the old native gentry in the early years after his acquisition of vast lands in East Galway in the Cromwellian period. Eyre claimed that in 1662, servants of Fergus Madden of Lismore and others, at the instigation of Fergus ‘came to the barn and haggard on the lands of Ballyhugh’, where John Eyre’s ‘servants were threshing his corn and turned them out and took possession’. This name continues into the modern period, not as an official townland name, but as a local placename, at the junction of the Eyrecourt to Banagher Road (R356) with the local road to Clonfert. Into the twenty first century a family named Staunton, resident at that junction, have for their address ‘Ballyhue’.

Ballymore: Refer to ‘Lawrencetown’.

Ballynaheskeragh: refer to ‘Ballynehaskeragh.’

Ballynebrannaghe: ‘Ballynebrannaghe’ was identified as containing one quarter in the 1585 Inquisition of the lands composing the barony of Longford. Given in the seventeenth century Books of Survey and Distribution as ‘Ballybranngh or Walshtown’ in the parish of Killoran. The alternative name of Walshtown would appear to derive from a direct translation from Irish, with the ‘brannagh’ referring to ‘Breatnach’, a Welshman or Walsh. Given on Petty’s Map in the parish of ‘Killowran’ as ‘Ballinemrana’, to the south west of ‘Clonlaghan.’ An inquisition taken in October 1605 stated that Annaghe Duff O Madden was found in rebellion and that he was seised in fee of one third cartron of ‘Balmcbramaghe’. The same inquisition found that another rebel, Dermode reoghe O Madden was also seised in fee of land in ‘Ballimbrannaghe’. (R.C. 9/14 Galway, Henry VIII-Wm III, Reporteries of Inquisitions Exchequer). John King of Dublin esq. in the third year of the reign of King James I was granted, among other lands, one third cartron in Ballenebrannagh, parcel of the estate of Annagh Duffe O Madden of the same, slain in rebellion and in the same, one half cartron, the estate of Dermod reogh O Madden of the same, slain in rebellion. (Cal. Pat. 3 James I) Five years later, the Earl of Clanricarde was granted a chief rent out of the same lands. (Refer to O Madden family of Longford, etc.) In the sixteenth year of the reign of King James I, Brazill mcShane O Maddin of Ballinabrannagha in Galway co., gent. held one quarter of Ballinabranngha in addition to other lands. One Owen O Maddin of Ballinebranagh was given as a head of family and one of the dispossessed landowners in 1664 whose lands was confiscated by the Cromwellian authorities and whose names were submitted to the Lord Lieutenant in that year for consideration for reinstatement.[v] The will of Brasil Madden of Ballinamranagh in the diocese of Clonfert was proved in 1747.[vi]

Ballynedehy: Refer to ‘Meelick.’

Ballynehaskeragh: ‘The townland of the Esker’, modern townland of Ballynaheskeragh, in the District Electoral Division of Portumna. Given as Ballihisker in the parish of Killimor on Pettys Map. Refer to ‘Treacy’ under ‘families.’

Ballyvaheen: a townland within that part of the parish of Abbeygormacan that lies within the barony of Longford, at one time part of a denomination referred to as Edrugilmore. Refer to ‘Addergoole.’

Bankfield: a local place-name in the townland of Kilnaborris, parish of Clonfert immediately to the west of a small bridge identified as Esker bridge. Bankfield occurs on William Larkin’s 1819 Map of County Galway in the general vicinity of Kilnaborris but south of the public road between Eyrecourt and Banagher. The name Bankfield does not occur on the 1838 O.S. map, but does occur on the later 25 inch map. An area named ‘Monkfield or Gorta Purta’ is identified in a deed of 1762, when James Moore and his wife Mary Moore alias Madden, daughter of Ambrose of Derryhoran, set to James Madden of Kilnaborris, gentleman, twenty five acres of land in the townland of Kilnaborris, commonly called Gortafurth, ‘lying between James Maddens place and Esker and by the old mill’. One Bryan James Madden was seated at ‘Monkfield’, in the parish of Clonfert in 1798, when he leased among other lands those at ‘Gorta Purth, otherwise Monkfield’ to John Hubert Moore of Shannon Grove. (Registry of Deeds, Bk. 555, p.64)

Gorta purta or Gortafurth appears to be an Anglicisation of the Irish ‘gort an phoirt’, ‘the tilled field of the bank’, the ‘port’ or ‘bank’ referring either to a river or stream bank or a turf bank. This, together with the description of it lying between Maddens house at Kilnaborris and Esker, would suggest that Gorta forth is the later ‘Bankfield’.

Bogganimore: Refer to ‘Lowpark’, parish of Killoran.

Boley: (pronounced locally as it would sound in the Irish language as ‘booly’ as in ‘buaile,’ a dairy place), the site of a Domincan convent or church, the site of an earlier convent in ruins to the rear, a later National School and a house on the 1838 O.S. Map. The public road between Portumna and Eyrecourt, that runs in front of this ecclesiastical site and house was significantly altered between 1838 and the start of the twentieth century.

Bouluskeagh: The townland of ‘Bouluskeagh or Flowerhill’, on the west side of the Kilcrow river, in the parish of Tynagh, Co. Galway. Annabella, sister of the builder of Derryhiveny castle and daughter of John mcDonnel mcBrasil O Madden of Derryhiveny married Daniel Madden of ‘Boluske’. Given as ‘Boholaskea’ in the Books of Survey and Distribution, part of the estate of Brassell Mc Farriagh Kittagh O Madden in the parish of Tynagh about 1641. Thomas Nugent was the recipient of part of this O Madden’s estate at ‘Boholaskea’ in the Cromwellian redistribution of lands. An Inquisition of 1585 detailing the extent of the barony of Longford in east Galway gave ‘Boylosky’ as containing nine quarters and so appears to have originally referred to a much larger area in that area of Tynagh west of the Kilcrow river than is covered by the early modern townland of ‘Bouluskeagh or Flowerhill’.

T. S. Ó Máille, referring to the townland of Bolosky in the parish of Killanin, states that both John O Donovan and P.W. Joyce gave the derivation of the name as coming from the Irish ‘buaile uisce’ or ‘watery buaile,’ the latter a dairy location.[vii] Ó Máille, however, contended that the place-name may rather have originated in the Irish word ‘boilsce,’ indicating a ‘bulge,’ which he takes to be associated with the Irish word for a rounded stomach ‘bolg.’ He asserted that the roundness suggested by the Irish word may have been applied to a feature in the natural landscape such as a rounded hill or similar, such as could be found in the townland he surveyed in the parish of Killanin. A similar rounded hillock could also be found in the Tynagh townland of ‘Bouluskeagh or Flowerhill,’ around which the Kilcrow river wound, between that raised ground on the west bank and raised ground on the east bank in the townland of Lismihill. As the area about Flowerhill is generally hilly and the area of ‘Boylosky’ referred to a larger area in the late medieval period, it may also refer to a collection of other hillocks also in that area.

Brackloon: a townland in the parish of Clonfert, deriving its name from a combination of the words ‘breac’, indicating something speckled and ‘cluain,’ a meadow. Refer to ‘Brackloon’ under ‘Architecture’ and ‘O Madden of Brackloon’ under ‘families.’ Refer also to ‘Cloonkea’ in this section in relation to alterations made to the boundary between Brackloon and Cloonkea, which left the tower house of Brackloon situated in Cloonkea.

Brendanstown: a place-name in local use only, as opposed to an official place-name, relating to an area located about a minor public road in the townland of Clonfert Demesne, parish of Clonfert. The origin and age of this place-name is uncertain but a denomination referred to as ‘Gortbrenan’ was listed alongside another, known as ‘Gortbealroyd’ in the 1407 Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert and may have been a reference to this later ‘Brendanstown’.[viii] In that rental list ‘Gortbrenan’ is listed shortly after the town of Clonfert and immediately before nearby townlands of Coolacurn, Cllonkea, Brackloon and others in that general vicinity.

Cagalla: Cagalla once formed part of the property of Rory McCollo O Madden of Brackloon in the late sixteenth century. It appears to have been in the parish of Clonfert, being listed jointly with Lisbeg, but separately from the adjoining townland of Blacksticks, in the early nineteenth century in the Tithe Applotment Books.

Callow Beg: a townland on the banks of the River Shannon in the parish of Meelick. The name is derived from the Irish word ‘caladh,’ used locally in the eastern region of County Galway to refer to low-lying river meadow called ‘callows’ bordering the River Shannon liable to flooding, the grass of which is often cut in summer for hay or winter fodder for livestock. Callow Beg translates as ‘the small callow’ as opposed to the adjacent townland of Callow More or ‘the large callow’ in the same parish.

Callow More: Refer to ‘Callow Beg.’

Camus: A townland in the parish of Meelick bordering the river Shannon. From ‘camas’ in the Irish language a winding river inlet or a bend on a river, derived from the word ‘cam’ a bend or a bent, crooked object.

The word was also used in describing individuals, ie. Donal cam O Sullivan Beare, Count of Bearehaven, a prominent Munster rebel of the Nine Years War, whose perilous mid-winter retreat from West Cork to the temporary safety of O Rourke of Breffni took him through numerous hostile territories, including that of Donal O Madden of Longford castle in east Galway in January of 1603.

Carrowclare: Refer to ‘Meelick.’

Carrowgare: Carrowgare appears on Petty’s seventeenth century map in the vicinity of the later Eyrecourt Demesne in the parish of Donanaghta and appears to have been one of the older townlands that would constitute that later townland in the creation of the demesne by the Eyres. Lands in Carrowgar formed part of the estate of Shane mc William oge O Lorcan who was killed in rebellion during the Nine Years War. The quarter of Carowgare was held in the reign of King James I jointly by Hugh oge O Madden and Melaghlin McHugh oge O Madden.

The name appears to translate as ‘the short quarter’, a quarter being an old measure of land equating in principal to a quarter part of a larger measure or estate known as a bailebetagh. The actual size or acreage of a quarter varied depending on the quality of the land in question forming the denomination and a quarter in turn was composed of four cartrons. In the Irish language a quarter translated as ‘ceathrú,’ from which ‘Carrowgar’ (‘an ceathrú gearr’ or ‘the short quarter’) derived its name.

Carrowkeanagh: referred to as being in the parish of Donanaghta in 1641 and, with lands in Killevny, Ballyhoose, Gortecarde and Clonshease, parish of Clonfert where Teig son of Hugh Daly was allocated lands by the Cromwellian authorities about the 1650s. Among those who possessed land in the quarter of Carrow-Ichoiny in the sixteenth year of the reign of King James I were Hugh oge O Madden and Melaghlin McHugh O Madden, jointly holding one third of a quarter and Conor boy O Madden of Carrow-Ichoiny, holding another third. In 1610 one sixth of a quarter of Carrowynkynyne or Karrownykynin was among the parcel of lands formerly held by Art McDermott O Madden, attainted.’ (Calendar of Patent Rolls of Chancery of Ireland, 7 James I, p. 162. LXVII.)

Cartronaceapanamallagh: Described as ‘Cartronaceapanamallagh, lying in Annaghcorba in the parish of Clonfert, barony of Longford, parcel of the lands of Annagh Duffe O Madden and Dermot Reogh O Madden, slain in rebellion.’ This parcel was among other lands in the barony of Longford granted to Gerald Earl of Kildare in the seventh year of the reign of King James I. The same two O Maddens held lands in Ballybrannagh. (Cal. Pat. 7 James I). By virtue of the inclusion of ‘cartron’ in its name, it would appear to have been a cartron or a fourth part of the quarter of Annaghcorba. The original meaning of this denomination is uncertain but may have referred to ‘the cartron of the level patch of land of the cattle.’ ‘Ceapach’ indicates a ‘tillage plot’ or a ‘level patch of land’ in the Irish language while ‘eallach’ may refer to ‘cattle’ or ‘livestock,’ the genitive singular being ‘eallaigh’ and the genitive plural ‘eallaí.’ Refer to ‘Ballybrannagh’, ‘Annaghcorba’, etc.

Claggernigh: Appears as ‘Clegarna’ on Petty’s map. Refer to ‘Knockmoydarregg’

Clonesmucke: Appears as ‘Clonesmost’ on Petty’s Map. Refer to ‘Knockmoydarregg.’

Clonreliagh: Refer to ‘Springfield’. Identified as ‘Clonreliagh’ in the parish of Killoran on Petty’s Map.

Cloonikinan: Modern townland of Cloonykeevan on Redmount Hill. In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 the denomination is given as ‘Cluain I chiabhain’.[ix] Refer to Madden family, etc.

Cloonkea: A townland in the parish of Clonfert. In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 the denomination is given as ‘Cluainche.’[x] The boundaries of this townland were altered at some point in the nineteenth century to include within its perimeter the tower house of Brackloon. Until the mid to late nineteenth century that tower house lay within the adjacent townland of Brackloon. The dividing boundary ran along a stream running on the east side of the castle. By the late nineteenth century the boundary was altered on Ordnance Survey maps to run along the centreline of the public road on the west side of the castle, thereby rendering the castle in Cloonkea. Refer to ‘Madden of Brackloon’ under ‘families’, etc.

Cloonkela: A place-name in the modern townland of Muingbaun, in the south of the parish of Kilquain. Given as ‘Cloonekellogh’ and variations thereon in seventeenth century sources. Land in this denomination was held by various O Maddens at that time who were described as ‘of Cloonekilly’ or alternatively as ‘of Moveffe’ or ‘the Moye,’ suggesting that the area known as ‘the Moye’ (from ‘maigh’, ‘a plain’) was located in the southern end of the parish of Kilquain. Refer to ‘Madden of Derryhiveny’ under ‘families.’

Cloonshease: Divided in the modern period into the townlands of Cloonshease (Daly) and Cloonshease (Persse), it was given in the mid seventeenth century Books of Survey and Distribution as the quarter of Clonecease in the parish of Clonfert. In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 the denomination is given, alongside ‘Syonacha mc an esgaib’, as ‘Cluavn na sessa’.[xi] (It is noteworthy that the spelling of denominations in the 1407 Rental appear to be close to the original Gaelic spelling or version of the placename.)

Coolacurn: Divided into the two townlands of Coolacurn North and Coolacurn South at a cross roads (known locally in the twentieth century as ‘the four roads’) in the parish of Clonfert. This townland appeared as ‘Cullakerne’ in the mid seventeenth century Books of Survey and Distribution. In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 the denomination is given as ‘Culrachayrin’.[xii] The name derives from a rounded hill, translating as the rear of the rounded hill’, from a combination of ‘corn’ and the word ‘cúl’ or rear.

Coolcartan: In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 this denomination is given as ‘Calcerdcha’.[xiii] Given on Petty’s Map as ‘Coolecarton’. Modern townlands of Coolcarta West and Coolcarta East. Refer to Lorcan, Kelly, Pelly families, etc.

Coolnebrannagh: Bryan James Madden was seated at ‘Monkfield’, in the parish of Clonfert in 1798, when he leased lands at ‘Coolnebrannagh alias Kilnaborris, otherwise Shannongrove, otherwise Madden Grove and other lands to John Hubert Moore of Shannon Grove. In the mid nineteenth century Hubert Butler Moore leased Shannongrove, a house and lands in the townland of Killnaborris, parish of Clonfert, from Belinda C. Madden.

Corballybeg: Refer to ‘Corballymore.’

Corballymore: Both the townlands of Corballymore and Corballybeg lie within the parish of Donanaghta. The former should not be confused with the nearby Corballymore in the parish of Abbeygormican, which lies in that part of the parish in the barony of Leitrim. The latter appears to have been referred to at one time as Corballynegall or ‘Corbally of the foreigners’ and formed part of the extensive lands (for the most part in the parish of Kilreekill) of the Anglo-Norman Wall family. (Refer to ‘Wall family’ under ‘families’ and to ‘Barony of Leitrim’ under ‘Placenames.’)

The name itself appears to refer to an irregular-shaped ‘baile’, ie. a township or settlement, Corballymore indicating the large irregular-shaped settlement and Corballybeg the smaller.

Crescent Island: A small island to the southwest of Incherky, between Meelick and Lusmagh that was incorporated into a land bank to form part of the western bank of the channel south of Marlborough footbridge.

Crockaunduff: (pronounced locally as ‘crookawndoo’) a local placename given on the 1838 Ordnance Survey Map as the location of a graveyard, about a gravel pit and on a sandy hill near the side of the public road, in the townland of Killnaborris. This was said locally to have been a childrens burial ground. (children were buried there as late as the beginning of the twentieth century, with one Jack Curran who lived at Esker reportedly having brothers or sisters who were buried there.)

Cromwell’s Island: An island on the River Shannon immediately to the rear, or east, of the Franciscan friary at Meelick. This island lay on the principal crossing point on the river Shannon and by the start of the seventeenth century a fort was constructed on this island, near the medieval castle of Meelick, to guard the river pass. Given its strategic location, the fort was attacked on a number of occasions in the seventeenth century and a gun battery was located at the fort to add to its defensive capabilities. P. O Keefe, when compiling information from local informants in 1838 on the history of the area, was told that the island was known in Irish as ‘Gutáile’, on which stood what was believed to have been a castle, no trace of which then remained.

An account of the area about Meelick friary in 1833 (The Dublin Penny Journal, No. 74, Vol. 2, Nov. 30th 1833, pp. 172-3) described the River Shannon at Meelick as being ‘here romantically picturesque; being broken into rapid falls. On one side is a round tower surrounded by three twenty-four pounders, and inhabited by military, one of whom civilly ferried me over the river Shannon, and on the other side, as if in quiet contrast, is an ancient and dismantled battery, crowned by the rude monastery before described.’ The dismantled battery is that on Cromwell’s Island, and with regard to its construction, one John D’Alton, describing the features about Meelick friary in 1847, referred to the presence of a ‘sodded fort’ within sight of the friary ruins. (‘The Gentlemans Magazine’ 1847, ‘families of Co. Galway’, pp. 39-40)

As a result of Shannon navigation works, this island was rendered almost indistinguishable from the mainland as low-lying uneven land between the friary church at Meelick and the modern bank of the River Shannon. To contain flooding, an embankment was constructed in the twentieth century along the western riverbank and traversing the site of the fort, the remains of which have since disappeared. In the twenty first century, this embankment was utilised as a raised public walkway for recreational purposes along the riverbank from Meelick to Portumna.

Crowsnest: A townland in that part of the parish of Clontuskert in the barony of Longford. It was suggested that the name Crowsnest derived from a connection with the family of Baldwin Crowe of Belmont, Kings County, one time land agent for the Eyre family who leased land in the vicinity prior to 1746 and appeared on early maps as Cullyderry. It is unlikely that the name derived solely from this Crowe family, however, as the denomination is given on Larkin’s 1819 map as ‘Atteepreechaun or Crowsnest.’ Given that the word for a crow in the Irish language is ‘préachán’, it is likely that ‘Crowsnest’ is a translation of ‘áit tighe phréacháin’, the place of the crow’s house or residence’ or ‘áit an phréacháin’, the place of the crow.’ While neither Atteepreechaun nor Cullydarry appear in the list of denominations in the mid seventeenth century Books of Survey and Distribution or on Petty’s mid seventeenth century map, the placename ‘Atteepreechaun’ predates the arrival of the Eyre family in the mid seventeenth century or any connection with a family named Crowe. In 1604 one ‘Dermod McBrien of Attiprechan, yeoman’ was given alongside many about Clontuskert and O Madden’s country granted a general pardon by the Crown.[xiv] Crowsnest would therefore appear to be a direct translation into English of the original Irish placename.

Culbane: The modern townland of Coolbaun West in the parish of Killimor. John King of Dublin, in the third year of the reign of King James I, was granted among other lands, ‘In Rathmore, one cartron, in Cowlebane, one half cartron, parcel of the estate of Donogh mcWilliam Newnagh of Rathmore, slain in rebellion. Refer to O Farrell family, etc.

Curragh: Refer to ‘Knockmoydarregg’

Derreenaphuca: shown as a small copse of wood on the verge of boggy ground in the townland of Moorfield or Gortnamona in the late nineteenth century. Refer to ‘Irish root words.’

Derreen: Given as Derin in the parish of ‘Kiltermore’ on Pettys Map. Modern townland of Derreen, parish of Kiltormer. Refer to ‘Irish root words’ and to ‘O Mulvihill’ under ‘families,’ etc.

Derrybawn: A local placename as opposed to an official townland, located in the townland of Kilmacshane (Turbett), parish of Clonfert, about or to the rear of the house occupied in the mid to late 1990s by one Hugh Kelly. It would appear to have been located in the general area about the junction of Kilmacshane townland with those of Killoran and Cankilly. While the ‘derry’ element, from the Irish ‘doire’, refers to the previous existence of an oak word, it is unclear if the ‘bawn’ element is derived from ‘bán’, that is, the colour white, or, given its proximity to the tower house at Brackloon, from the Irish noun ‘badhun’, the cattle enclosure or walled area that surrounded a tower house in the medieval period.

Derryhoran: A townland in the parish of Meelick. Appears as Derryohoren in the parish of Meelick on Petty’s mid seventeenth century map to the northwest of Derrimcfena, to the west of Moyre (Mowoyer). Refer to O Madden family of Derryhoran, etc.

Derrymcfinola: Appears as Derrimcfena in the parish of Meelick on Petty’s mid seventeenth century map to the southeast of Derryohoren and to the south of Moyre (Mowoyer). ‘Part of the lands of Derrymacfennela otherwise Prospect’ was advertised to be sold by public auction in the Landed Estates Court on 20 November 1863. The property to be sold at that time composed the modern townland of Prospect Demesne and the sole tenant of the house and lands of Prospect Demesne at that time was Joseph Henry Cowan, who held his lease by an agreement dated 14 February 1853.

Refer to ‘Madden of Curraghboy and Fahy’ under ‘Families’.

Dromglew: Dromglew appears to be the townland identified circa 1641 as the quarter of Drumnegleine, in the parish of Kiltormer, Co. Galway. About 1618 the quarter of Droniglem was part of the estate of Melaghlin O Madden of Clare, gent. Refer to Callanan family, etc.

Donanaghta: ‘Dunanaghta’ was one of three dúnta or strong fortified places and seventeen townlands, according to the Registry of Clonmacnoise, that Cairbre Crom, ancient chieftain of the territory of Ui Maine or Hy Many, bestowed upon the Abbey of St. Kieran of Clonmacnoise. The name appears to relate to what was formerly a fortified place on high ground on the eastern side of Redmount Hill, near and to the north of the later village of Eyrecourt. The site of this dun appears to have been absorbed into the later townland of Eyrecourt Demesne, which was created from a number of older denominations sometime after the mid seventeenth century. The ruins of a former building known as Donanaghta Church lay within the sub-circular boundary of Doon graveyard in the townland of Eyrecourt Demesne. This dún gave its name to the parish of Donanaghta (known also as the parish of Eyrecourt), a variant of which spelling was ‘Doonanoughta.’ The dún or its former denomination would appear to have been referred to up to at least the mid seventeenth century as ‘Down mcMearan,’ ‘Downemickmeneran,’ ‘Dwnmacmerran’ or variants thereof. The placename ‘Donanaghta’ appears to be an Anglicisation of the Gaelic ‘dún an uchta’ or ‘fortified place of the breast’, a reference to the breast of Redmount Hill upon which it sits.

Shane roe mcTeig of Dwnmacmerran was among those pardoned in 1586 (Fiants Eliz I). One Donogh boy mcHugh of Downvickberra was among those pardoned in 1585, while Richard mcDonnogh boy O Madden held land in the townland about 1641, as did Donnogh Mc Brassell O Madden of Lismore and Teige Mc Downy Mc Teige and John Duffe Mc Rory O Madden, when it was given as ‘Doonecunaram’, parish of Doonanoughta. John Lawrence of Ballymore, about 1618, held a third quarter of Downemickmenaran. In the mid 1650s Donagh O Madden was ordered to transplant from ‘Downimarrane’ by the Cromwellian authorities and allocated 28 profitable Irish acres in the parish of Ballynakill in Co. Galway. (R. C. Siminton, The Transplantation to Connacht 1654-1658, Irish Manuscripts Commission, 1970, p. 159.)

Refer also to ‘Knockmoydarregg.’

Esker: a large townland in the parish of Clonfert forming part of the western bank of the River Shannon. Much of the land is composed of bogland to the north and to the south a sandbank or ‘iascar’ from which the townland derives its name. Low-lying riverside meadows known as ‘callows,’ prone to flooding and cut for hay or silage in the Summer, formed the southern edge of this townland along the Shannon.

The bridge built over the Shannon at Banagher in the modern County Offaly enters Esker on the Galway side of the river. The principal public road from the bridge continued on to Eyrecourt along the sandbank and was known locally as the ‘High Road’ and branched off to the north within the townland in the direction of Ballinasloe.

Given the strategic importance of the bridge in the seventeenth century a fortification was built on the Esker bank known later as ‘Cromwell’s Castle’ and in the early nineteenth century a Martello tower was constructed to strengthen the position. In the late seventeenth century a large Jacobite army crossed the bridge to attack Birr or Parsonstown and the bridge was the scene of some fighting as the Jacobite forces retreated into Connacht. This early stone bridge was replaced in the nineteenth century in the general vicinity of the former.

The townland formed part of the estate purchased by the English merchant James Collier Harter in the mid nineteenth century, who had a primary school erected therein for the education of his tenant’s children. Esker schoolhouse continued in that capacity until the late twentieth century.

Rear of Esker Schoolhouse, viewed from the North-East, erected at the expense of James C. Harter in the mid-nineteenth century.

Esker Island: a small island on the River Shannon opposite the townland of Esker, parish of Clonfert.

Eskerboy: a townland within that part of the parish of Abbeygormacan that lies within the barony of Longford, at one time part of a denomination referred to as Edrugilmore. Refer to ‘Addergoole.’

Eyrecourt: Refer to ‘Killeneho’ and ‘Killelehy fort.’ A village and parish of that name in the Roman Catholic diocese of Clonfert, the latter known also as the parish of Dononaughta. This Dononaughta derived its name from a dún or fortified place on the side of Redmount Hill near the later village of Eyrecourt but the name has been used in the modern period as the Irish language version of the name of the village. While Dononaughta originally referred to the dún and the parish thereabout, the village developed about the denomination of Killenihy within that parish and as such the original Irish form of Killenihy is a more correct Irish version of the village name. Lewis in his Topographical Dictionary of 1837 gave the population of this ‘market and post-town’ as 1789 and containing 342 houses.

The village of Eyrecourt was founded by John Eyre, a Cromwellian who acquired extensive estates in east Galway in the mid to late seventeenth century. He had a large county seat constructed at the townland of Killenihy or ‘Killeno’, in the parish of Donanaughta called Eyrecourt Castle, built on the grounds of an earlier O Madden house.

By 1677 he had constructed a small Protestant chapel at what would be one of the entrances to his residence to serve the needs of his family and what was a small community of Protestant settlers whose presence he had facilitated in the area.

In view of Eyre’s building of his church and having ‘brought several Protestant families together’ ‘and in order to promote and encourage an English plantation there’ the King by patent dated 5th February 1679 created Eyre’s lands and others at Eyrecourt into ‘the Manor of Eyre-Court, with five hundred acres in demesne; power to create tenures; to hold court leet and baron and a law-day or court of record; to build a prison; to appoint seneschals, bailiffs, gaolers and other officers; to receive all waifs, estrays, fines, &c.; to impark five hundred acres in free warren, park and chase; to hold a market on Wednesday and two fairs more on 29th June and on Thursday after twelfth day, and the day after each at Eyre-Court.’[xv]

The grant of 1679 significantly altered the landscape about Eyrecourt thereafter. The demesne lands Eyre created lay principally to the north and east of his mansion, while on the edge of his demesne a small planned village developed, its main street leading to the western gates to the demesne. While it is possible a small cluster of houses may have existed in close proximity to the earlier house of the Maddens at Killenihy the village which developed about the western gates of the demesne appears to have been one of the first planned villages in east Galway.

About 1837 a market was held on Saturdays and fairs were held annually on the Monday after Easter Monday, June 29th, July 9th, September 8th, one in October and December 20th.[xvi] The town at this time had a court house, gaol and a constabulary police station. The Protestant parish church, erected in 1677 by John Eyre, was at that time in poor repair, while the Roman Catholic church at the east end of the town was being built in 1824 at the expense chiefly of Christopher Bernard Martin of Eyrecourt.[xvii] A more modern Protestant church would be built later in the century on Church Lane.

Farrenesker: Appears on William Larkins map 1819 as Tharananiska in the modern townland of Esker at the River Shannon crossing at Banagher. The half quarter of Farrenesker was one of various parcels of lands held by John O Madden, head of the O Madden family, in the late 1630s as part of his estate in the barony of Longford (Books of Survey and Distribution). Both ‘Isker and Farrin Isker’ were listed together in the Tithe Applotment Books dated 1824 relating to the parish of Clonfert.

Farringean: Refer to ‘Longford’.

Farrintire: Refer to ‘Longford.’

Ferryfeingall: Refer to ‘Longford’.

Flowerhill: the modern townland of ‘Bouluskeagh or Flowerhill’ in that part of the parish of Tynagh in the barony of Longford in South East Galway. Refer more details refer to ‘Bouluskeagh.’

Friarsland: Refer to ‘Meelick.’

Fynagh: A denomination in what was in the early modern period the then parish of Clonfert. In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 the denomination is given as ‘Finagh mc Eaghagain’.[xviii] The MacEgan family were associated with this townland from an early period and in 1615 the Protestant Bishop of Clonfert listed the ‘Eiganes’ as a family who detained land or rent from the Bishop in the two quarters of ‘Finegh.’

Glennavaddoge: Refer to ‘Meelick.’

Gloster: a townland in the parish of Lusmagh, once part of County Galway and part of the ancient lands of the O Maddens and now part of County Offaly. In the early seventeenth century, among other lands, the ‘two quarters of Glasdarragh’ were confirmed on John Moore of Cloghan Castle. The spelling of the denomination rendered at that time may imply that the townland may have originally derived its name from a green oak wood.

Gortecharda: one of the denominations given as part of the estate of Hugh O Dallaghan in the late 1630s in the general vicinity of Killevny in the parish of Clonfert and in the parish of Donanaghta.

Gortnalug: a townland in the parish of Kiltormer. The denomination was also known as Dangin, as evidenced by a deed dated 4th December 1734 between Collum Kelly ‘late of Danging als. Gortnelog but now of Ballyvoly in the County of Gallway, gent. of the one part and Edward Eyre of the Town of Gallway, Esquire, of the other. (Registry of Deeds, Dublin, Lib. 79, p. 114, no. 54885.) A senior branch of the Lorcans were seated at Dangin in the early eighteenth century and in the adjoining townland of Graveshill also in that same century.

Gortnaskermore: Appears as ‘Gortnakmore’ on Petty’s Map. Refer to ‘Knockmoydarregg.’

Gortrea: Given as Gortrea or Fairfield in the District Electoral Division of Kilmalinoge at the Census of Ireland 1901 and 1911. In 1618 three O Cormicans of Kilmalanock jointly held a moiety or half of the cartron of Gortrea. Refer to O Cormican, O Kelly families, etc.

Grange: modern townland of Grange, parish of Fahy. In the mid seventeenth century the quarter of Grange was composed of the half quarter of Grange called Lisnegrange and the half quarter called Lisdonnell.[xix] The former was held in the late 1630s by John Donnellan of Ballydonnelan and the latter by Florence Callanan of Grange, whose family appears to have had resided there for some time. The former refers to a ringfort or lios named for the grange itself and the latter from a lios which in the Irish language translated as the lios of Donal or Domhnall, a man’s personal name. No liosanna were indicated on the nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps of the townland of Grange. In the 1854 Rental of the Eyrecourt Castle estate the townland of Grange was shown divided by the Eyrecourt to Killimor road into two parts, south and north; the former smaller than the latter. The southern portion was identified as ‘the lands of Grange or Donnolly Grange’ while the northern was given as ‘the lands of Blake’s Grange’.

A number of granges were mentioned in the Anglo-Norman cantred of Síl Anmchadha in the 1333 Inquisition taken into the extent of lands and dues of the murdered de Burgh Earl of Ulster.[xx] Two granges in need of substantial repairs were recorded at that time as being located in ‘Monbally’ within Síl Anmchadha but this would not appear to equate with the lands about Fahy. One definition of a grange was that of a farm or farm buildings attached to a monastic settlement but often geographically separated from the monastery itself and often used for storage or crops or grain.

In medieval east Galway the word appears to have been used to refer to such a monastic farm and was rendered in the Irish language ‘grainseach.’ About 1487 a canon of Clonfert stated that the monastery of St. Mary at Boyle in the diocese of Elphin had a property lying at a distance from the abbey, in the diocese of Clonfert and known as ‘Granseachuneynmayge.’[xxi] The denomination refers to a grange and while there is no suggested connection between this denomination and that Grange in the parish of Fahy, it is noteworthy that the canon described this former grange as having been ‘from time immemorial’ ‘granted to both clerks and laymen to farm or yearly pension’ and sought to have it let to him for life. He undertook to increase the cess due to the monastery at Boyle from the farm and to repair the grange buildings, one of which was a church. While there is no evidence to suggest any church was founded at the grange in the parish of Fahy, it is likely that this was also a farm with associated buildings serving an abbey.

Within the Fahy townland of Grange a structure identified as ‘Grange House’ and another nearby associated structure were shown on the early nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps within what was once known in the 1850s as ‘Blake’s Grange.’ By 1854 the building known as ‘Grange House’ had disappeared and it did not appear on the map of that townland associated with the Rental of the Eyrecourt Estate of that year. By the latter decades of the nineteenth century another separate house nearby within the townland was then referred to as ‘Grange House.’ Both that and some ancillary buildings that had once stood in the vicinity of the original ‘Grange House’ had disappeared by the late twentieth century with a farmyard located in the vicinity of the latter and a modern house located in the vicinity of the former.

A ‘standing stone’ was also identified in this townland, near ‘Grange House’ on early nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps.

Refer to the Callanan family, etc. under ‘families.’.

Graveshill: a townland in the parish of Kiltormer. Bernard (or Brian) Lorcan ‘de Crickana na Hougnidh’ died in April 1748 and was buried in the Lorcan chapel at Meelick.[xxii] This would appear to be an anglicised version of the Irish place-name ‘Cruachán na huaighe’ or ‘Cnocán an huaighe’, which translates as ‘the hillock of the grave’.[xxiii] As such, it would appear to relate to the townland of Graveshill, where a senior family of the name were seated into the nineteenth century.[xxiv] One of more prominent of the Lorcan family residing locally at the end of the eighteenth century was Joseph Lorcan of Graveshill, whose death in 1800 was recorded by the Meelick friars. He was likewise buried within the Lorcan Chapel.[xxv] This family’s seniority is further confirmed by its association with the Lorcan Chapel at Meelick in the early nineteenth century. In 1816 that chapel would be referred to on at least one occasion as ‘Lorkin’s chapel of Graves Hill.’[xxvi] When Lorcan’s estate was advertised to be let in The Dublin Evening Post newspaper dated 7th February 1797 it was described as ‘the lands of ‘Graves-hill otherwise Knockanewhoey.’ As ‘n’ is sometimes pronounced ‘r’ in the noun ‘cnoc’ (a hill) in some dialects, it would confirm the identity of ‘Crickana na Hougnidh’ as ‘Graveshill.’ It is noteworthy that part of the lands of Graveshill, once part of Lorcan’s estate, was identified as ‘Sheaneaghy’ when it was advertised for sale in The Dublin Evening Post dated 10th June 1809 and was a corruption of the adjacent townland name of ‘Skenageehy.’ A graveyard is depicted on the peak of a small hillock in the townland of Graveshill on mid and late nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps which local tradition in the early twenty-first century held to have been used at one time as a burial place for unbaptized children. Refer to ‘Larkin’ under ‘families.’

Gutáile: Refer to Cromwell’s Island.

Illaunaglee: a small island in the middle of the River Shannon opposite the townland of Keeloge in the parish of Meelick. This island disappeared as a result of Shannon navigation words in the mid nineteenth century.

Illaunandarragh: Refer to ‘Old Castle Island.’

Illaunaphuca: a small island in the the River Shannon, lying to the south east of the large island of Incherky, between Meelick and Lusmagh. Most of this island disappeared during works on the channel on the Lusmagh banks.

Illaunavegagh: a small island in the the River Shannon, lying to the south east of the large island of Incherky, between Meelick and Lusmagh. This island became part of the south eastern bank of Incherky during works on the channel on the Lusmagh banks.

Illaunawatia: a small island in the the River Shannon, lying to the east of the large island of Incherky, between Meelick and Lusmagh. This island became part of Incherky during works on the channel on the Lusmagh banks, and is now a piece of land to the north of local sluice gates and a bridge known as Marlborough bridge.

Illaunfadda: a small island in the the River Shannon, lying to the east of the large island of Incherky, between Meelick and Lusmagh, translating into English as ‘long island.’ This island became part of Incherky during works on the channel on the Lusmagh banks.

Illaunglass: a small island in the the River Shannon, lying to the east of the large island of Incherky, between Meelick and Lusmagh. This island became part of Incherky during works on the channel on the Lusmagh banks.

Illaunnaskehy: a small island in the the River Shannon, lying to the south east of the large island of Incherky, between Meelick and Lusmagh. This island became part of the south eastern bank of Incherky during works on the channel on the Lusmagh banks.

Keelogue: Refer to ‘Meelick.’

Killaltanagh: the modern townland of Killaltanagh, parish of Clonfert. Appears as ‘Kylathonagh’ on William Larkin’s Map of County Galway 1819. It would appear to translate literally from the Irish as the wood or the small church on a height in marshy ground, depending on the meaning of ‘kill’ in this case. In either event, it is an accurate description of the topography as the townland consists primarily of a large area of raised land falling away towards less fertile bogland on either side. Refer to ‘Irish root words.’

T.S. Ó Máille states that the nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan heard the ‘kill’ pronounced locally as ‘kyle,’ suggesting the Irish word ‘coill’ a wood.[xxvii] However, the initial syllable of the placename in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was solely pronounced ‘kill’ locally, suggesting a small church. O Donovan suggested its original meaning as ‘the wood of the knots.’ There were no native Irish speakers in the district in the mid twentieth century and O Maille noted that the local people pronounced the placename as (k’il’a:ltǝnǝ, k’il’altǝnǝ and k’ilantǝnǝ), the third form he held to be a corruption, used only be some younger people and a few older people.

Ó Máille suggests a translation of this name as ‘the wood of the bird flock’ equating the latter part of the placename to ‘ealtanach’ a little-used version of the adjective ‘ealta’, from the word ‘ealta’ ‘a flock of birds.’[xxviii] However, while the ‘kill’ may have been either a wood or church, it would appear much more likely from the local topography that the name was originally intended to indicate ‘the church or wood on a height in marshy ground or a bog,’ ‘alt’ being an Irish word to describe a height or high spot and ‘eanach’ a marsh or bog.

The townland was held in its entirety as part of the estate of a minor branch of the O Maddens. About 1618 Teig, Coagh, Ferdoragh and Melaghlin McDowny of Esker in Galway county, gentlemen, held jointly as their estate ‘the town and quarter of Killalta’ in Longford barony. In an inquisition of 1622, Ceahagh (ie. Coagh or Cobhthach) mcDonnagh O Madden was seised in fee of two cartrons and a half carton of land in Esker and Killaltanagh in the parish of Clonfert, among other lands in Killnaborris and elsewhere and his son and heir was given as Murrogh mcCeahagh, aged ten years and not married at that time. (R.C.4/14, Reporteries of Inquisitions Chancery, Co. Galway Eliz. -Wm. III). In 1585 Donogh mcCogh of Easker, cottier, who would appear to be the father of this Coagh or Ceahagh and the other three O Maddens, was among those granted a pardon in that year alongside Owen McMelaughlin ballow O Madden of Myleck, gentleman. (Owen of Lusmagh, the son of Melaghlin balbh O Madden) Killaltanagh was included in the considerable number of townlands in the barony of Longford granted to the Cromwellian John Eyre in the mid seventeenth century.

Killeen: identified as Killeen fort and a burial ground, in the townland of Kilmacshane, parish of Clonfert, on the 1838 O.S. map. As a circular enclosure or embankment and its use at one time, as is said locally, as a burial ground for unbaptised children, the ‘killeen’, as it was known locally, relates to ‘cillín’, a church or churchyard. It would appear to be from this site that the townland derives its name.

Killelehy fort: a small round embankment located immediately inside the former western or village entrance gates to Eyrecourt Castle and Demesne in the parish of Doonanoughta or Eyrecourt. Appears as ‘Killelehy’ on the 1838 Ordnance Survey Map but is erroneously given on later Ordnance Survey maps as ‘Killeleby fort’ from a misreading of the earlier map. From its name it would appear to refer to a small old church or churchyard site and to have been the feature from which the former area known as Killeneho derived its name.

The later village of Eyrecourt developed in close proximity to this site.

Various spellings of this name were given in different sources in the seventeenth century, such as ‘Killinehy’, ‘Killeneho’, ‘Killenno and variations thereon and refer to the former name of this area prior to the construction of Eyrecourt castle and the village of Eyrecourt in the late seventeenth century.

To the northeast of this embankment a branch of the O Madden family erected an early seventeenth century house that later formed part of the group of buildings at Eyrecourt Castle. An eighteenth century descendent of this branch, John Butler Madden, then resident in France, would describe his descent as ‘of the house and family of Killinehy, now called Eyrecourt,’ and from one Murtaugh son of Denys son of that Murtaugh O Madden who was dispossessed of his Killinehey estate in the Cromwellian period.

The spelling ‘Killinehy’ given by Butler Madden in the eighteenth century would appear to be closer to the original, given its derivation from the Irish word ‘cill’ or cillín’, a church or small church. (Refer to ‘O Madden family of Killinehy’, etc.)

In the mid-seventeenth century this denomination appeared in the Books of Survey and Distribution, prior to the creation of Eyre’s estate, as ‘ Killenno alias Killmigha Bodella and Killdalaffy.’ It is noteworthy that in the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 that the denomination is given as ‘Kilthaghlastra alias Killinhy’.[xxix] The preceding entry in the same ‘Rentals’ relates to the denomination of ‘Teagh Laistre’, a reference to a house or, in the Irish language ‘teach’, in that denomination. It would appear that the nearby ‘Kilthaghlastra’ may refer to a ‘coill’ or wood relating to the same ‘teach’ or ‘house.’ It is possible that the ‘Killdalaffy’ given in the Books of Survey and Distribution may have originally been intended as ‘Killdalassy’, closer to the 1407 version of the name and two of the letter ‘s’ been mistaken for two of the letter ‘f’. Part of the same lands appear in the parish of Clonfert in the Books of Survey and Distribution, as ‘Killtalastye’ when confirmed in the possession of John Eyre but, while was shown entered in the parish of Clonfert, he appears to have held it as ‘part of Killenelly and Brodella’, the latter two in the parish of Doonanoughta.

While the denomination was no longer in use in the vicinity of Eyrecourt by the late twentieth century, reference was made to the denomination in the mid nineteenth century when Robert Eyre, senior, of Eyrecourt, solicitor, was identified as a leaseholder with houses in the townland of ‘Killenaehy, parish of Donanought’ in his application for inclusion on the Register of Freeholders in April of 1846. (The Galway Mercury, Sat. April 4, 1846, p. 4.)

Killeneho: Appears as Killeneho on Pettys Map. ‘Refer to Killelehy fort.’

Killevny: A townland on the eastern slope of Redmount Hill in the early modern parish of Clonfert. In the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 the denomination is given as ‘Killaibne’.[xxx] The medieval quarter of Lisdavilla was incorporated, it would appear, into the modern townland of Killevny and is manifest now only in a ringfort of that name in Killevny. Refer to Madden family, etc.

Killimorbologue: Refer to ‘Toe Bolowgge.’ About 1838 the Ordnance Survey Letters for County Galway noted with regard to ‘the old church of Killimor, a short distance to the west of the village’ that ‘in the memory of Mr. McEgan (who lived near the old church) there was a chapel connected with the south side of this church, called Seipéal Uí Mhaoilcheir or Mulcary’s Chapel, which is said to have been built by a respectable family of that name whose burial place is there. This chapel was completely destroyed some years ago and the family have changed their old name of O Mulcare.’ The name Mulcare, Mulcary or Cary are not commonly found within the barony of Longford in east Galway.

Killine: Appears as Killin on Petty’s Map. Refer to ‘Knockmoydarregg’

Killinehy: Refer to ‘Killelehy fort.’

Kilmachugh: Refer to ‘Meelick.’

Kilmacshane: a large townland in the parish of Clonfert, translating as ‘the church or churchyard of the son of Shane.’ The name appears to derive from a ‘cillín’, a small church or churchyard, the diminutive of ‘cill’, identified as ‘Killeen fort and burial ground’ shown on the 1838 O.S. map as a circular enclosure or embankment. Local tradition refers to this site having served for a time as a burial ground for unbaptised children. Refer to ‘O Madden of Brackloon’, etc.

Kilmalanock; Kilmalinoge. Given as the parish of ‘Kilmolony’ on Pettys Map. Refer to the O Cormican family, O Madden of Derryhiveny, etc.

Kilnaborris: Refer to ‘Coolnebrannagh’.

Kilnagrehan: identified as Kilnagrehan fort, in the modern townland of Derreen on the 1838 O.S. map. Given as a circular enclosure or embankment, the ‘kill’ would appear to relate to ‘cill’, a church or churchyard.

Kiltormer: A parish and village in the barony of Longford. According to the Registry of Clonmacnoise, a quarter of land in Kiltormer was one of the seventeen townlands and three dúnta or strong fortified places that Cairbre Crom, ancient chieftain of the territory of Uí Maine or Hy Many, bestowed upon the Abbey of St. Kieran of Clonmacnoise.[xxxi]

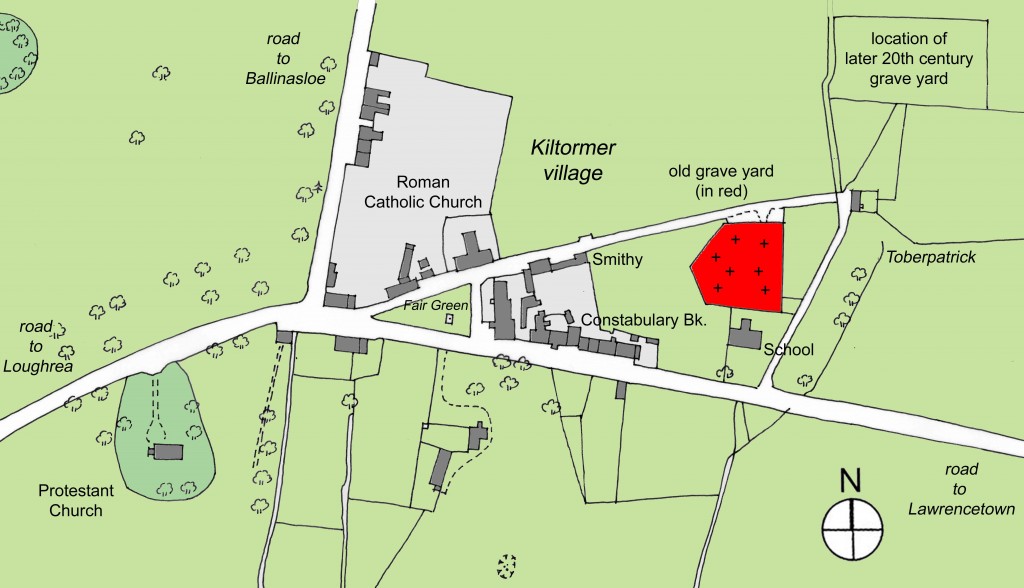

In the late fifteenth century Phillip ‘odownylay’ (ie. O Donnelly or O Donnellan), priest of the diocese of Clonfert was assigned the perpetual vicarage of the parish church of ‘Kiltormoyr.’ About late 1487 or early 1488 he presented a petition to the Papal authorities in which he referred to his having repaired and restored ‘at great expense’ the church at Kiltormer, which had prior to that time lain in ruin.[xxxii] The location of this early church is uncertain but it is likely to have been located at the old graveyard in the townland of Kiltormer West in the middle of the later village. In his 1838 Ordnance Survey Letters the nineteenth century Patrick O Keefe referred to the old Protestant church of the parish having once stood in that graveyard, in which church service was performed until a few years prior to O Keefe’s arrival. That church had been demolished before 1838, with only the foundation visible to O Keefe. (A new Protestant church ‘St. Thomas’s Church’ was constructed at Kiltormer about 1815 on a site given by Thomas Stratford Eyre.) It is possible that this demolished church was the earlier medieval church of the parish and may have been adapted for later Protestant use.

Map of Kiltormer village circa 1890s showing the location of the early church about the old grave yard (in red).

A small Roman Catholic church dating from about the early decades of the nineteenth century was constructed in the village, also in the townland of Kiltormer West and dedicated to St. Patrick. A holy well dedicated to this saint, known as ‘Toberpatrick’ lies to the immediate west of the old graveyard and the possible site of the medieval parish church. In the mid and late nineteenth century a triangular space in the village in front of the Roman Catholic church served as a fair green and in the late twentieth century as a car park.

A junior branch of the Cromwellian Eyre family of Eyrecourt were established at Eyreville to the north-west of the village and who gave the site for the construction about 1815 of the Protestant church in the village. Lewis in his Topographical Dictionary of 1837 gives the name of the village of Kiltormer as ‘Kiltormer-Kelly’ stating that it was at that time the estate of Charles Kelly, ‘a friar, whose ancestors founded Kilconnell Abbey and some others in this country.’ Lewis described it as ‘a rising village, in a well-cultivated district, within five miles of the Grand Canal and has cattle fairs on the 17th of February, May, August and November.’ He noted that ‘a fine quarry of black marble’ had recently been discovered in the vicinity.

Charles Kelly, ‘Dominican Fryar’ and Malachy Kelly, both with an address of ‘Bettyville, Aughrim,’ were among the five Catholic clergymen, one Protestant clergyman and five ‘lay gentlemen’ who appended their names to an appeal for clemency to the Lord Lieutenant and Governor General of Ireland in April 1836, requesting the commutation of the sentence imposed on the sixteen year old Edward Killilea and the fifteen year old Daniel McKeigue from Transportation for Life to Imprisonment. Both men had been found guilty of manslaughter. (The one Protestant clergyman who appealed for clemency was ‘M. Groome, Rector, Kiltormer Glebe.’) Malachy Kelly, when writing to Ambrose Madden of 112 Talbot Place, Dublin in January 1843, gave his address as ‘Bettyville, Kiltormer’ and informed Madden that ‘Fr. Charles’ had died but that the rest of the family were well. (RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 25-0-39/JOD/168). Three years later The King’s County Chronicle dated 26th August 1846 reported the death of Malachy Kelly, Esq. at Bettyville House, County Galway aged 80 years. The house known as Bettyville was situated in the townland of Cloonlahan (Eyre) in the parish of Killoran, to the west of the village of Kiltormer.

The ruins of Bettyville in the townland of Cloonlahan (Eyre) as it stood in 2015.

Prendergasts succeeded to the Kelly property of Kiltormer and in June of 1852 the estate of John Prendergast of Kiltormer, comprising approximately 196 acres of the townland of Kiltormer West, including the post and market town of Kiltormer and 59 acres of the nearby townland of Ballooly, was put up for sale in the Incumbered Estate Court. One Mr. Trench was recorded as the purchaser, paying £1,600 for the lands at Kiltormer West and £570 for the lands at Ballooly. (The Galway Vindicator and Connaught Advertiser, Sat. 26 June 1852) The property would appear to have been acquired soon thereafter by Alderman John Reynolds of Dublin, former Lord Mayor of that city, who held that office in 1850. Alderman Reynolds was in possession of the village of Kiltormer by early in November 1853, on one night of which one of his houses was set alight maliciously. (Galway Mercury, 12 November 1853) ‘Thom’s Almanac and Official Directory’ of 1862 have the address of Alderman Reynolds as 58 Charles Street Great, Dublin and Adrigoole, Kiltormer. The estate of Alderman Reynolds in the vicinity of Kiltormer was offered for sale in the Landed Estates Court in 1873 and January 1874. Refer to ‘O Madden’ and ‘Eyre’ under ‘families.’

Kiltormer Protestant Church viewed from the north

Knockmoydarregg: Knockmoydarregg covered a wide area in the late sixteenth century, and from its translation from ‘cnoc mhaighe dheirge’ into English as ‘the hill of the red plain’, equates with the area around the later local place-name of Redmount Hill. In the eight year of the reign of King James I, ‘Camgort in Knockmoiledearg’, containing one quarter of land, was confirmed in the possession of Richard Earl of Clanricarde.[xxxiii] This Camgort is located on the south-eastern slope of Redmount Hill in the civil parish of Donanaghta and is now part of the modern townland of Corballymore and Camgort. The modern Redmount Hill, one of the highest hills in the east of County Galway, is located between the villages of Eyrecourt and Lawrencetown. Knockmoydarregg given in the 1585 Inquisition into lands that formed the barony of Longford (formerly the territory of Síl Anmchadha) as containing forty-one quarters of which seven bore a chiefry (or small rent) to the Queen in right of the Abbey of Clonfert and five quarters to the Bishop of Clonfert. No modern townland bears, or former quarter appears to have borne, this name, encapsulating as it did many quarters in its own right.

These seven quarters bearing a chiefry to the Queen ‘as in right of the Abby of Clonfert’ appear to include the townlands of Killine, Rath, Curragh, Ballyhugh, Claggernigh, Gortnaskermore and Clonesmucke, five of which were one quarter each, while two were taken to be a half quarter each about 1641. (Books of Survey and Distribution) All of the above with the exception of Ballyhugh appear on Petty’s Map of the barony and all came to be combined later as the large townland of Abbeyland Great to the southwest of Redmount Hill and appear to have been lands once attached to the Augustinian foundation at Clonfert. The seventh quarter may have been the quarter referred to as ‘Down mcMearan’, from which the Clonfert abbey was due an annual rental income in an early seventeenth century inquisition relating to the monastery.[xxxiv] The location of the Clonfert abbey lands at the western foot of Redmounthill lends further evidence to that area as being the late-medieval area of Knockmoydarreg.

Another reference to the place-name appears in the pardon by the Crown in 1603 to one ‘William Mc Gillerneife of Knockmoildarige’, listed among the many individuals pardoned in that year. (Cal. Pat. Rolls, I James I, p.18)

Refer also to ‘Donanaghta.’

Lawrencetown: A village and a parish of that name in the Roman Catholic diocese of Clonfert. The official translation of the village on local signposts in the twentieth and twenty-first century as ‘Baile mór Shíl Anmchadha’ or ‘the large settlement of (the territory of) Síl Anmchadha’ would appear to be incorrect and has led to the mistaken belief that this was the location of a prominent township in the O Madden territory. The modern Irish State translation was taken from the original residence of the Lawrence family at Ballymore prior to their settlement at the nearby Lisreaghan but Ballymore townland and its castle lie adjacent to the modern village and it is clear from a number of sources that geographically the village and the modern townland known as Lawrencetown developed within the wider confines of what was originally the larger denomination of Oghil More. In addition to which the State’s translation of the village name may be doubly incorrect in that the overwhelming majority of seventeenth century and eighteenth century references to the Lawrence’s family seat give it as Billimore or Billemore rather than Ballymore which would suggest a derivation from the Irish noun ‘bile’, a sacred tree or in this case ‘bile mór’, a large sacred tree. The earliest known reference to the denomination now known as Ballymore occurs in the Episcopal Rental of the Diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 wherein it was given as ‘Iochailmore et Bilemore’, lending further credence to the view that the modern village and townland name may have been misconstrued.

The modern Roman Catholic parish of Lawrencetown formed part of the medieval and early modern parish of Clonfert. Founded about 1700 by Walter Lawrence, the senior representative of a family established about Ballymore in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, the village was reputed to have been remodelled at a later period. It was laid out in an ordered pattern along an east-west axis with two sub-circular open spaces at either end of the main street of the village. Lewis in his 1837 Topographical Dictionary described the village as having a chief constabulary police station with petty sessions held weekly on Thursdays. The police barracks was identified in Ordnance Survey maps of the mid nineteenth century as located in the western open space, terminating the western vista along the main street. About the centre of the eastern open space was located at that time a small market house. A fair was held at the village annually on May 8th, August 22nd and December 15th for cattle, sheep and pigs and Lewis noted that ‘a considerable quantity of wooden ware and furniture’ was manufactured there. At that time a ‘modern’ Catholic church, constructed prior to Catholic Emancipation, was serving the population of the village while the Weslyan Methodists also had a chapel and school, the former located on the road exiting the village in the direction of Clontuskert.

By the late nineteenth century the market house was identified on Ordnance Survey maps as a ‘court house’ while a new school had been erected across from the Roman Catholic church at the eastern end of the village.

Refer to ‘Oghil More.’

Leire: In the confirmations of lands in the sixteenth year of the reign of King James I John oge O Lorkan and James O Lorkan of Cullecartan in Galway Co., gent. were jointly possessed of a half quarter of Cullecartan in Longford barony, and alongside Thomas O Kelly of Clontuskert, jointly held a third quarter of Leire.[xxxv] On Petty’s Map Lyre is shown in the parish of Clonfert, between Coolecartan (later ‘Coolcarta’) and Annaghcorba (later townland of Annaghcorrib), to the north east of Coolecartan. In the Tithe Applotment Books dated 1824 relating to the parish of Clonfert ‘Annacorrib and Lyre’ were treated together. From its original meaning in the Irish language as ‘ladhar’, it signifies a fork or the area formed between a fork in a geographical feature such as between rivers. In this case it would appear to signify an area between two streams.

Lisanacody: The modern townland of Lisanacody in the parish of Dunanoughta outside of the village of Eyrecourt and also the site of an O Madden castle of that name. In a list of castles of the territory dated approximately 1574, Lisanacody was erroneously included under the barony of Leitrim and given as ‘Lisnacode’, the residence of one Murrogh mcfferigh. The error may have occurred in confusing the townland of Lissenhackett in the adjacent barony of Leitrim with Lisanacody. Morogh mcRory of Lissenhackett was given as one of the chief men of the barony of Longford in 1585. Moraigh keigh mcFeary of Lisnackody, gent., received a pardon in the second year of the reign of King James I and was earlier described in a pardon of 1585 as Murcho mcFerriagh of Lyssenackett (Cal. Fiants, Eliz. I.) (In that same second year one Donnogh mcMoraghe of the same was also pardoned.) It is evident that this is the same man as Murrogh mcfferigh of Lisnacode of 1574 and so it would appear evident that the Morogh mcRory mentioned in the 1585 Indenture should correctly be Murrough mcFeary O Madden.

In the 1670 documents whereby the first John Eyre of Eyrecourt made provision for the future settlement of his estates upon his heirs mention is made to ‘the castle. towne and lands (ie. townland) of Lissenaccody’. The denomination of Lissanacody did not appear among the extensive lands in the barony of Longford confirmed in 1666 unto John Eyre under the Acts of Settlement and Explanation but ‘Lyssanacody alias Corballybegg’ was among a number of lands in the vicinity confirmed unto Erasmus Spelman in the same year. It appears therefore that between 1666 and 1670 Eyre acquired the same from Spelman. (NLI, Dublin, PP 941, Public Records Ireland, Reports, Fifteenth Annual Report, 1825, pp.79-80.) In a deed of mortgage dated October 1710 dealing with considerable lands in the barony of Longford reference was made to ‘the castle with a good house thereunto adjoining called Lissnecoaddy and an orchard containing 2 quarters of land.’ It again appears in 1737 when Colonel John Eyre of Eyrecourt leased to Charles Donelan of Lissenacody, gent. ‘the castle, town and lands of Lisenacody, Cloghbrack and Brideall (recte Bodella) containing as Staffords Survey 198 acres of land.’ No obvious trace of the castle remains.

Lisbeg: A townland in the parish of Clonfert. In the Rental of the diocese of Clonfert dated 1407 it would appear to equate to the denomination called ‘Leathrathabeg’,[xxxvi] the ‘rath’ and ‘lios’ being similar in denoting a more or less circular enclosure or space enclosed by such an enclosure.

Liscoyle: shown as a circular lios or ringfort in the townland of Lispheasty. A townland of that name also in the parish of Abbeygormican, refer to ‘Lysychwill’.

Lisdawilly: a substantial lios or ringfort, identified as Lisdavilla in the 1838 Ordnance Survey map of Ireland as located in the modern townland of Killevny. Refer to O Madden family of Killevny, etc.

Lisdonnell: The half-quarter of land called Lisdonnell, located in Grange, parish of Fahy. Appears as Lisdonell on Petty’s Map. Refer to Callanan family, etc.

Lisgrange: Appears as Lisnagrange on Petty’s Map. Refer to Grange and Lisdonnell, parish of Fahy.

Lisheenduff: a lios or ringfort of that name, given in the modern townland of Clooncona on the 1838 O.S. map.

Liskeevan: an irregular shaped embankment, near and to the west of ‘Killevny fort’ in the modern townland of Killevny.

Lismafadda: a small circular embankment or raised area in the modern townland of Fearmore, adjacent to the townland of Lismafadda. Lismoyfadda was given as being composed of three quarters of land in the inquisition into the extent of the barony of Longford in 1585.

Lismore: a townland in the parish of Clonfert. Refer to ‘O Madden of Lismore’ under ‘Families.’

Lisnahitteen: a ringfort within the townland of Addergoole within that part of the parish of Abbeygormacan that lies within the barony of Longford,

Lisnarabia: a large lios or ringfort in the townland of Abbeyland Great, parish of Clonfert. Not distant from this lios is the site of another unnamed lios or circular embankment, over which the minor public road, known locally as the ‘Abbeyland Road’ or ‘Corkscrew Road’ traverses.

Lisnatrap: a lios or ringfort, identified as Lisnatrap fort, near Kilmurry graveyard, in the modern townland of Skecoor, parish of Kiltormer on the 1838 O.S. map.

Lispheasty: a large rectangular shaped embankment, near the lios of Liscoyle in the townland of Lispheasty.

Lisphubble: a lios or ringfort in the townland of Abbeyland Great, parish of Clonfert, near the sites of Abbeyland House and Abbeyland Cottage in the early nineteenth century.

Lissaballa: although named as a lios or ringfort in the modern townland of Bellview or Lissareaghaun, in the modern parish of Lawrencetown on the 1838 O.S. map, it is a large rectangular banked enclosure, apparently originally accessed from the narrow southern end, near a residence identified as Frenchpark in the nineteenth century.

Lissanska: A lios or ringfort identified on the 1838 O.S. map as being divided between the modern townlands of Skecoor and Feagh, near the modern townland of Garrison.

Lissatogher: a number of liosanna or ringforts, identified as Lissatogher forts, in the modern townland of Skecoor, parish of Kiltormer on the 1838 O.S. map. The name appears to derive from the ringfort’s association with a ‘tóchar’ or timber walkway or causeway laid over a bog or marsh.

Lough Cunaboy: a small pool of water and also a placename in the townland of Portumna, identified on the 1838 O.S. map as on the side of the modern public road (R355) leading from Portumna to Lawrencetown. Cunaboy and its lough are situated near Wellmount House, not distant from Portumna.

Lough Derg: A large lake between Portumna and Killaloe on the River Shannon bordering east Galway and the southern boundary of the barony of Longford. The antiquarian John O Donovan, quoting in the early nineteenth century what he referred to as the best Irish authorities, gives the original name in Irish of this lake as ‘Loch Deirgdheirc.’[xxxvii]

Longford: The location of the principal chiefry castle of the O Maddens in the late sixteenth century, from which the barony derived its name. Given in the Books of Survey and Distribution in the mid Seventeenth Century as the two quarters of ‘Ferryfeingall alias Longford and Farringean and Farrintire.’ Appears on Petty’s Map in the parish of Teranasker (modern ‘Tiranascragh’) as ‘Therefarringall.’ Refer to ‘O Madden of Longford’ under ‘families’ and ‘History.’

The ruins of Longford Castle in the parish of Tiranascragh.

Loughaunbrone: a small pool of water by the side of the public road in the townland of Abbeyland Great, parish of Clonfert.

Lowpark: a modern townland in the parish of Killoran. In a deed of 1795 Lieutenant Patrick Burke sold to his brother-in-law Thomas Longworth Dames lands in the parish of Killoran which included ‘Boganmore otherwise Bagganemore otherwise Bugganemore otherwise Bagone otherwise called Lowpark.’ This townland was also given as ‘Bogganimore’ and various other variations and formed part of the lands confirmed on a branch of the MacHubert Burke family of Isertkelly under the Act of Settlement following their transplantation to Killoran in the mid seventeenth century. The Jacobite Captain Garrett Burke was described as of ‘Clanrillie’ or Clonreliagh in 1694 and later in the early eighteenth century as ‘of Bogganimore’. Refer to ‘the Burke family of Clonreliagh’, etc.

Lysychwill: Also Liscuoill (half quarter of Liscuoill held by Nicholas O Hanin of Castleheyny in Galway County, gentleman, Cal. Pat. Rolls, 16 James I, p. 416) Modern townland of Liscoyle, parish of Abbeygormican. Refer to McSweeney, O Hannin family, etc.

Macknihany: Shane Enylln of Macknehany, husbandman, was granted a pardon alongside others of the barony in 1585 (Cal. Fiants Eliz.) In the third year of the reign of King James I John King was granted lands ‘in Monechadin, one third quarter, parcel of the estate of Shane-en-Ellan O Maddin of Macknihany, attainted.’ The Earl of Clanricarde was granted a chief rent in the eighth year of the reign of King James I out of lands ‘in Nehany alias Macnehanie, one fifth of a quarter and Inisherick, one fifth of a cartron and in Killoran in the barony of Longford, six parts of one quarter; parcel of the estate of Awly oge O Madden of Killoran, attainted.

Meelick: The name is a variation upon the Irish word ‘Milic’, a marsh. It has been suggested that the gaelic origin of this word is derived form a combination of ‘magh’ (a plain) and ‘fliuch’ (wet).

A parish and townland within that parish located along the banks of the Shannon river and some of which is liable to flood. Also in the medieval period a manor and a borough therein, the site of a castle strategically located at an important river crossing and later defensive fortifications. Also from the late medieval period the site of a Franciscan friary, all within the same parish.

The Manor of Meelick was established by the Anglo-Normans about the castle and consisted in the late medieval period of the four quarters of Carrownekilly, Killmachugh, Carrowclare and Ballynedehy. The four quarters of the Manor lay principally to the west and north of the castle and embraced the later townlands of Killmachugh, Kilhonerush or Woodlands, Keelogue, Meelick, Friarsland, Glennavaddoge and several islands in the Shannon about two river crossings.

Kilmachugh continued as a townland of the same name into the twenty-first century, while Carrownekilly may be identified as Kilhonerush alias Woodlands from Petty’s mid-seventeenth century map as situated between the two branches of the Eyrecourt River prior to their entering the Shannon. This would suggest its correct translation as ‘ceathrú na coille.’ The early eighteenth century map of Lord Bophin’s Meelick estate coincides with the boundaries of the earlier manor and shows a heavily wooded area described as Meelick Wood in the area of the later Woodlands townland. The modern townland of Friarsland, about the fifteenth century Franciscan foundation, would appear to have incorporated the site of Meelick Castle as it stood in 1557. Meelick appears to relate to Carrowclare, ‘the quarter of the plain,’ given its identity in the 1830s Tithe Applotment books as ‘Meelick Plains’ and its location on Petty’s map. The exact location of Ballynedehy is unclear, but from Petty’s map appears to coincide with the townland of Keelogue. Neither Keelogue or Glennavaddoge are treated in early records as distinct entities, and appear to have been part of the four quarters. The early seventeenth century grant of the Manor to the Earl of Clanricarde describes its composition in detail, and refers to a number of islands in the Shannon as included within the Manors boundaries.

Richard Burke, 4th Earl of Clanricarde bought the Manor of Meelick by 1611, only three years after Sir John King acquired the property from the Crown. In that year Clanricarde’s Meelick property was described in detail as ‘the manor or castle of Meeleeke or Mylock in the Yallowe island upon the Shannon, containing one stang of land; to hold four quarters in Meelicke, free from Composition rent – another castle in Meeleeke – a hall, and another castle – another island adjoining to the Yallowe island – a small village near Mileeke, and six cottages, 120 arable, six acres wood, bog and pasture – two islands on the Shannon, the greater containing 30 acres of boggy pasture and the lesser 10 acres – three weirs upon the Shannon, and all other hereditaments of said manor, rent, 3l 6s 8d.’ That one of these castles in the Manor is that located on the now disappeared island known as ‘Old castle Island’ is evident from another contemporaneous account of the Manor as ‘the manor and ruinous castles of Milick in the river of Shanen (with four quarters) the castle of Illanedarragh in Mylick with certain islands in the said river, belonging to Mylick, of which Manor of Milicke all the lands are holden by knights service.’ Clanricarde received a licence in 1617 to hold a market at Meelick on Saturdays and a fair on the feast of St. Matthew. He claimed in 1618 that he had purchased the Manor at a dear rate, and had by that time built a house ‘within the precinct’ at a cost of 10,000 li. The Earl paid rent on a ferry also at Meelick, which, in 1623, was not returning a rental income, being without a tenant at the time.

For further details of the manor, castle and friary refer to ‘History’ and to various associated families such as Madden, Burke, Moore, Larkin, Cuolahan, etc. under ‘families.’ Also Refer to ‘Old Castle Island’ in this section and ‘Illanedarragh’ under ‘Architecture.’

Monkfield: An area named ‘Monkfield or Gorta Purta’ is identified in a deed of 1762, when James Moore and his wife Mary Moore alias Madden, daughter of Ambrose of Derryhoran, set to James Madden of Kilnaborris, gentleman, twenty five acres of land in the townland of Kilnaborris, commonly called Gortafurth, ‘lying between James Maddens place and Esker and by the old mill’. One Bryan James Madden was seated at ‘Monkfield’, in the parish of Clonfert in 1798, when he leased among other lands those at ‘Gorta Purth, otherwise Monkfield’ to John Hubert Moore of Shannon Grove. (Registry of Deeds, Bk. 555, p.64)