© Donal G. Burke 2016

Captain John Eyre

Captain John Eyre, an officer in the Cromwellian army in Ireland, was the seventh son of Giles Eyre of Brickworth in Wiltshire by his wife Jane Snellgrove and descended from the Eyres of Wedhampton and Northcombe, a family long established in Wiltshire.[i] During the Civil War in England between the Royalist supporters of King Charles I and the Parliamentarians, the Eyres of Brickworth supported the Parliamentary forces. Their house was plundered by the Royalists as a result.[ii]

Captain John Eyre was said to have accompanied the Cromwellian General Ludlow, a native of Wiltshire and one of the signatories to the death warrant of King Charles I, to Ireland and it is likely that it was about that same time that his younger brother Edward also arrived in Ireland[iii]

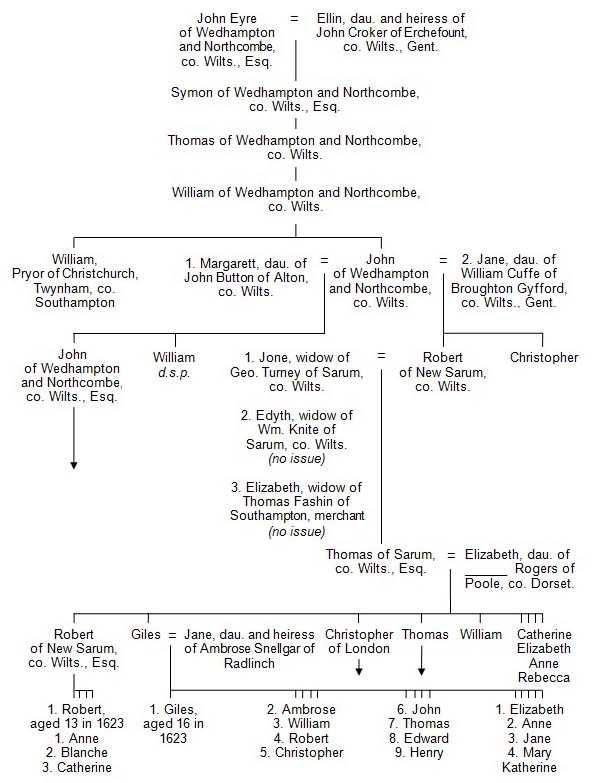

Pedigree of the Eyre family of Wedhampton and Northcombe and New Sarum, derived from the heraldic visitations of Wiltshire of 1565 and 1623. While Captain John Eyre’s funeral certificate described him as the seventh son of Giles of Brickwork and Jane Snellgrove, the 1623 visitation gave him as the sixth son and his younger brother Edward as the eighth son of Giles and Jane, daughter and heiress of Ambrose Snellgar of Redlinch in Wiltshire.

Acquisition of east Galway estates

Following the fall of the town of Galway in 1652 and the subsequent defeat of remaining Roman Catholic and Royalist forces, the Cromwellian government set upon the large scale confiscation and reallocation of Roman Catholic estates.[iv] John Eyre was appointed in 1657 to a commission established to allocate and distribute property in Counties Galway and Mayo and within a short period of time became one of the principal acquirers of lands in east Galway, in addition to other lands in west Galway, King’s County, north Clare, Tipperary and elsewhere.[v]

Captain John Eyre married Mary, daughter and co-heiress of Philip Bigoe of Newtown, King’s County by his first marriage, prior to 1659.[vi] Bigoe was of Huguenot (French Protestant) origin and had established a glassworks at Gloster across the Shannon in the parish of Lusmagh by the late 1630s or 1640 and acquired the tower-house of Newtown in that parish, formerly the property of an O Madden and his heir by marriage, a McHugo or McCooge. His castle was attacked and his property suffered damage during the 1641 Insurrection, the precursor to the Cromwellian campaign in Ireland, but had been restored to his estates, including his lands in County Clare and would later hold the position of High Sheriff of Kings County prior to his death.

In the Cromwellian period Eyre acquired extensive lands in the parishes of Meelick, Donanaughta and Clonfert, in the heart of what had been the ancestral territory of the O Maddens. Prior to the 1641 Rising the lands acquired by Eyre in east Galway were for the most part those of various O Maddens, O Horans, O Kellys, certain lands claimed by the Protestant Archbishop of Tuam and Bishop of Clonfert, parcels of the Earl of Clanricarde estates and included lands of such families as the Lawrences, who, although of recent English origin, were Roman Catholic and Royalist. The lands about his descendant’s later seat of Eyrecourt, however, he acquired not by Cromwellian grant but by purchase in the mid 1650s.

The purchase of lands in the parish of Donanaughta

In 1652 the Cromwellian Commissioners of Revenue at Galway set to Captain John Eyre ‘the castle and lands of Clonfert in the barony of Longford, County Galway, formerly belonging to the Popish Bishop of Clonfert and now in disposal of the Commonwealth.’ (British Library, BL Egerton Ms 1762, Commonwealth Papers 1650-1659, p. 206.) By at least 1656 John Eyre was resident at Clonfert, being described as such in a surviving land transaction of June of that year involving both Philip Bigoe of Gloster and Eyre on the one part and one Teige McNamara and his wife on the other and relating to lands in County Clare. He was again described as ‘John Eyre of Clonfertt’ in another land transaction of September of that year in which he purchased from Sir Thomas Esmonde, Bart., five hundred acres in the parishes of Donanaughta and Clonfert. Although given in the transaction as ‘of Claddagh, half barony of Ballymoe in the County of Galway’ Esmonde was originally seated at Limerick in the parish of Kilcavan in County Wexford whence he and his wife Lady Joan Esmonde and son Laurence had been ordered to transplant by the Cromwellians. They were allotted 3,427 acres in total, five hundred of which lay in the parishes of Donanaughta and Clonfert and it was the lands in these two latter parishes that Eyre purchased. They were described specifically as ‘the town and lands of Killeno alias Killmigho, Bodella and Killdallaghty two quarters and one third of a quarter containing one hundred and forty acres, Killtallaffy, half a quarter fifty nine acres, Kinahan two quarters and a half one hundred fourty six acres and in Culecartron one quarter one hundred fiftie eight acres containeing in all five hundred acres and lying in the parish of Donenaghty and Clonfertt Barony of Longford and county of Galway.’[vii]

Much of these lands purchased from Esmonde about 1656 in the parish of Donanaughta would later provide the site for Eyre’s mansion and accompanying demesne. Eyre was still described as ‘of Clonfert’ in the following year in another legal document of October 1657 and his eldest son John was given as born at Clonfert in or about 1659. Although the exact location of his residence at Clonfert is not detailed it would appear to have been the Protestant Bishop’s Palace in that parish, corresponding to the castle referenced in 1652 by the Commissioners of Revenue.

John Eyre’s brother Edward, who served as Judge Advocate in Coote’s Parliamentary army, established himself in the town of Galway, where John Eyre likewise acquired some property.[viii]

The ruined remains of the former Bishop’s Palace at Clonfert, wherein it was reputed that Captain John Eyre resided prior to the construction of Eyrecourt Castle. Evidence points to Eyre residing initially at Clonfert in the mid 1650s and later at Ballymore, then in the parish of Clonfert, on what had formerly been the lands of the Lawrence family.

Restoration of the monarchy

Following the turmoil of the Cromwellian period and government by a Republican-dominated Parliament, the monarchy was restored in the person of King Charles II in 1660. The restoration presented the threat to Eyre of the return of all or part of his newly acquired estates to the families of their original proprietors. An Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time. The new monarch was slow to undo the earlier Cromwellian settlement of land, as he himself was a Protestant King of a Protestant England deeply suspicious of Roman Catholicism. There was also a strong Protestant interest group composed of certain newly arrived Protestants and those longer established in Ireland who did not wish to see Roman Catholicism rehabilitated. Unable to adequately balance the interests of the dispossessed and those fearful of losing their new estates and with insufficient land to placate all, the Act of Settlement would leave many disenchanted.

The King declared that all those Cromwellian adventurers and soldiers would be left in possession of their estates with the exception of those the monarchy regarded as particular enemies, such as those directly involved in the killing of the king’ father King Charles I. Those Roman Catholics found innocent were also to be reinstated to their lands and the Cromwellians then in possession of that Catholics holding was to be compensated elsewhere. The solution proved unsatisfactory to many but allowed for many Cromwellian landholders settled in Ireland to retain the majority or part of their estates.

John Eyre had a number of influential acquaintances and managed to retain a large part of his estates in east Galway after the restoration, establishing himself as one of the most prominent Protestant landholders in the county. With interests in the town of Galway alongside his brother Edward he was appointed Mayor of Galway Corporation and his brother Recorder in 1661, where at least the younger brother was accused of preventing certain Roman Catholics from regaining possession of their property in the town.[ix] Both men were also elected Members of the Irish House of Commons in 1661 representing the town of Galway. It was claimed that in the summer of 1662, a favourite of the King visited Eyre, presenting him with a portrait of the king ‘richly set in brilliants’ as a sign of favour.[x] In 1663 he served as a Justice of the Peace for County Galway.[xi]

His position locally was far from comfortable, in that he met with active resistance from several of the old native gentry and others with property interests in the area, including Fergus Madden of Lismore. The head of a branch of the O Maddens who had held extensive lands in the parish of Clonfert about their castle at Lismore, the lands of Fergus Madden had been confiscated to provide for a vast estate for Henry, son of Oliver Cromwell, along the Shannon from Portumna to Clonfert. Cromwell was allowed to keep his estate under the Act of Settlement and sold what had been Madden’s land and elsewhere to the Earls of Cork and Arran, from whom Madden now rented his former lands. In 1662 Loughlin reagh Madden and Rory Madden, the servants of Fergus Madden of Lismore and others, at the instigation of Fergus ‘came to the barn and haggard on the lands of Ballyhugh’ (part of the modern townland of Abbeyland Great, in the parish of Clonfert), where John Eyre’s ‘servants were threshing his corn and turned them out and took possession’. The disputed lands were in this case in the vicinity of Eyrecourt, part of the lands formerly attached to the Clonfert abbey and not distant from Madden’s Lismore lands. Eyre complained to Parliament about Madden and also complained about others who had seized his cattle on the lands of Kilaltenagh and Kilmacshane and still detained the same.[xii] The Sheriff of Galway was ordered to have Eyre’s possessions returned and the offenders were called to answer for their activities before the Dublin parliament.

He similarly encountered opposition in the same locality from the Anglican Bishop of Clonfert about early 1663. Eyre held a number of houses in the townland of Clegernagh, near Ballyhugh, (both of which would form part of the modern townland of Abbeyland Great) which the Bishop claimed was the Church’s rightful property. The Bishop had a number of his tenants in the same houses but Eyre broke into one of the houses wherein were three tenants, drew his sword and turned them out. One of tenants, ‘Daniel Freaghra’ he wounded on the head ‘whereof he languished a long time afterwards’ and dragged him outside, reputedly shouting that he now had possession. The Bishop informed the Irish House of Lords in March of that year but the House of Commons confirmed Eyre in possession and in addition ordered Eyre to be put in possession of another of the Church of Ireland’s houses in Clegernagh.[xiii] An accommodation was reached not long thereafter between the Bishop and Eyre.

Ballymore

By at least 1665 and for most of the late 1660s John Eyre was residing at the tower house of Ballymore, formerly the property of the Lawrence family on the western plateau of Redmount Hill, not distant from Clonfert. The former occupants had arrived in east Galway by the late sixteenth century as servants of the Elizabethan administration and had acquired a large estate in what had been O Maddens ancestral territory. Having had their estate confiscated in whole or in part by the Cromwellian authorities and allocated other lands nearby, Ballymore castle and farm was eventually acquired by Eyre but it appears that he may have leased it initially as a settlement he made of his estates in 1670 made reference only to lands in ‘Ballymore alias Lismanny’ in his ownership but made no mention of the castle of Ballymore. (The same settlement made mention of Brackloon castle in the parish of Clonfert and that of Lisanacody in Donanaughta among his other properties.) He was recorded as resident at Ballymore in 1665 and still in 1667 and 1668. Eyre retained ownership of Ballymore farm and later generations of the family would lease the same, with the tower-house, to members of the Seymour family, but he appears to have left there by 1670 as, in that year, John Eyre and his wife Mary were described as ‘of Killenehy, County Galway’.[xiv]

Eyrecourt Castle

In the midst of hostile neighbours and an uncertain political climate John Eyre sought to consolidate his hold on his lands as early as possible. Eyre began construction work on the building of a large county seat for himself at the townland of Killeno alias Killmigho (variously given in the seventeenth century as ‘Killenehy,’ ‘Killenihy’ and also ‘Killenno als Killmigha Bodella & Kildalaffy’ or Killeny) in the parish of Donanaughta between Redmount Hill and Meelick. The mansion, called Eyrecourt Castle, was built on lands he had earlier purchased from Sir Thomas Esmonde, Bart. and on the grounds of a long robust two-storey early-seventeenth century house, similar in many respects to the Protestant Bishop’s substantial residence at Clonfert, formerly the property of a dispossessed branch of the O Maddens. The existing house was retained and incorporated into the collection of ancillary buildings to the rear of the new house. In a settlement Eyre made relating to his property dated 13th December 1670 he and his wife were described as ‘John Eyre of Killenehy in the County of Gallway, Esquire and Mary his wife one of the daughters and coheire of Phillip Bigoe late of Newtowne in the King’s County, Esquire, deceased.’ The first property listed in that settlement was ‘the capitall house, bawne, towne and lands of Killenehy als Eyrecourt.’ The reference is one of the earliest if not the earliest surviving use of the newly coined place-name ‘Eyrecourt’ but it is unclear if the ‘capitall house’ refers to the earlier O Madden house or Eyre’s new mansion. As it was named ‘Eyrecourt’ it is likely that it may refer to the new house but the presence of a bawn wall suggests that the site about the house was still at least partly fortified at this stage.

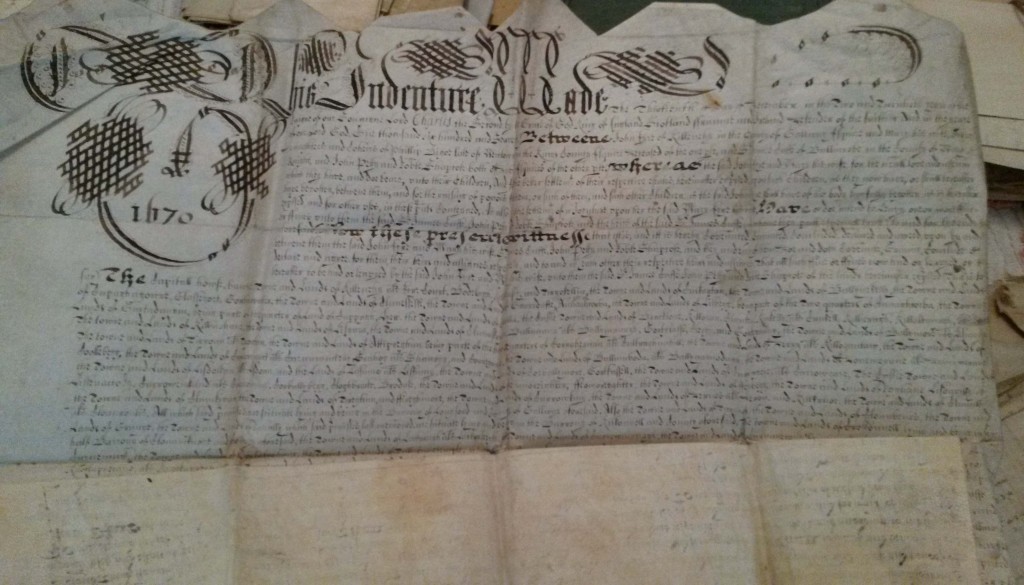

The settlement of his extensive property made in December 1670 by John Eyre of Killenehy and Mary his wife, in which are mentioned ‘the capitall house’ and ‘bawne’ of Killenehy alias Eyrecourt’.

Eyrecourt Castle

By 1677 he had constructed a small Protestant chapel at what would be one of the entrances to his residence to serve the needs of his family and what was a small community of Protestant settlers whose presence he had facilitated in the area. In view of Eyre’s building of his church and having ‘brought several Protestant families together’ ‘and in order to promote and encourage an English plantation there’ the King by patent dated 5th February 1679 created Eyre’s lands and others at Eyrecourt into ‘the Manor of Eyre-Court, with five hundred acres in demesne; power to create tenures; to hold court leet and baron and a law-day or court of record; to build a prison; to appoint seneschals, bailiffs, gaolers and other officers; to receive all waifs, estrays, fines, &c.; to impark five hundred acres in free warren, park and chase; to hold a market on Wednesday and two fairs more on 29th June and on Thursday after twelfth day, and the day after each at Eyre-Court.’[xv]

The grant of 1679 significantly altered the landscape about Eyrecourt thereafter. His new mansion, built in an architectural style new to the country and situated as a classical object in an ordered and landscaped demesne, announced his arrival as a significant landed proprietor and the arrival of a new order in the county and country. The demesne lands he created lay principally to the north and east of his mansion, while on the edge of his demesne a small planned village developed, its main street leading to the western gates to the demesne. A small community of minor Protestants was evident at an early stage in the life of the village, bearing such names as Banco and Canneville, who would later be buried in the small graveyard about Eyre’s chapel.[xvi] While it is possible a small cluster of houses may have existed in close proximity to the earlier house of the Maddens at Killenihy the village which developed about the western gates of the demesne appears to have been one of the first planned villages in east Galway.

The large expenditure involved in the creation of this new built environment left Eyre in debt and early in 1677 a trust was established in which a portion of his estate was placed for a period of sixty-one years to deal with the arrears.[xvii]

He continued active in the local government of the county, being entrusted various tasks by the powerful and influential Duke of Ormonde, including measures taken in the late 1670s to hamper a suspected rising among Roman Catholics across the country. In 1681 he served as Sheriff of County Galway.

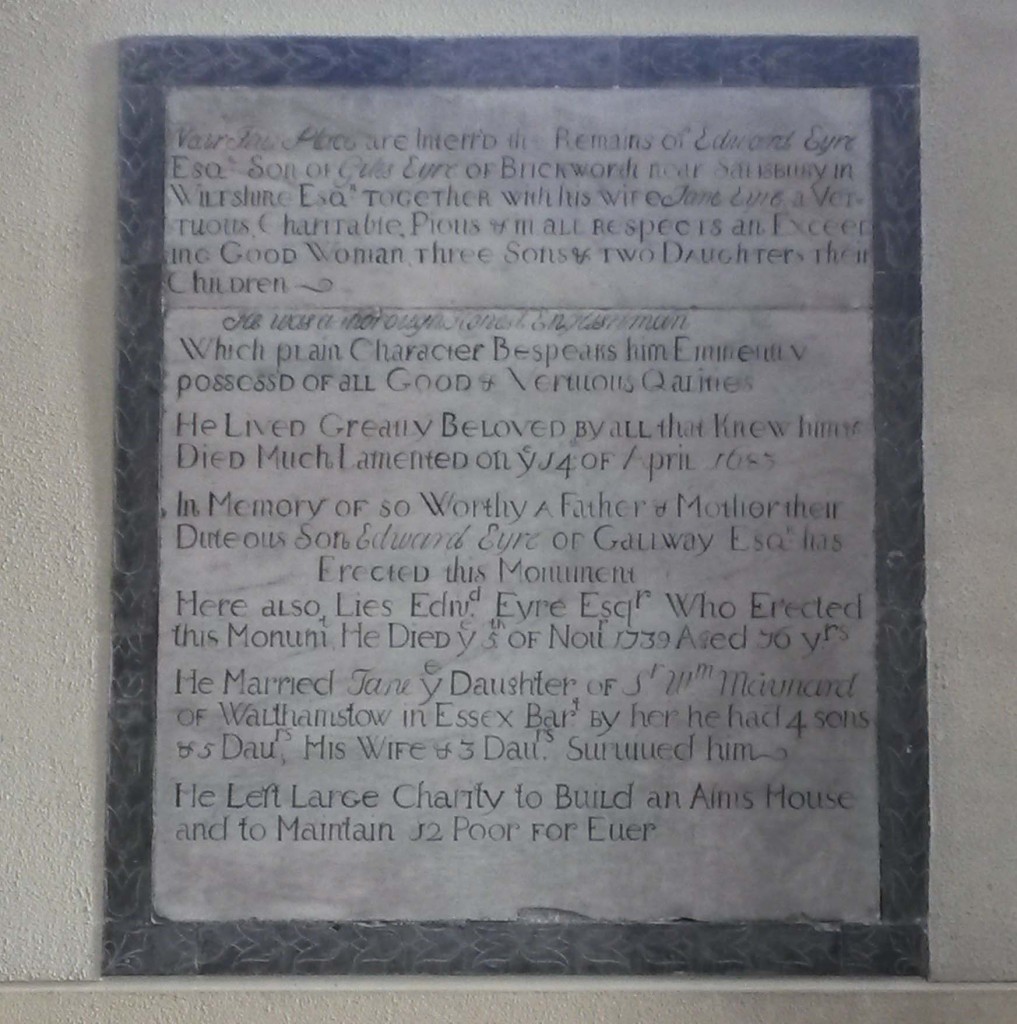

John Eyre’s brother Edward died on the 14th April 1683 and was buried in the College Church of St. Nicholas in the town of Galway.[xviii] (His funeral certificate was signed by his sister Jane.)

Memorial tablet in the College Church of St. Nicholas in Galway, commemorating Edward Eyre ‘a thorough honest Englishman’, brother of John Eyre of Eyrecourt and Edward’s wife Jane, erected by their son Edward of Galway.

‘One of His Majesty’s Most Honorable Privy Council of Ireland,’ it would appear that John Eyre of Eyrecourt was in ill health by early 1685. In late March he made his will, appointing his wife Mary as executrix. In his will he made mention of three of his six children by Mary Bigoe; his son and heir John Eyre the younger, his other son Samuel and his daughter Anne. Two children; Rowland and Katherin, had died unmarried before their father. It would appear no mention was made in John Eyre’s will of his elder daughter Mary, who was at that time married to George Evans of Ballygranane, County Limerick. He also made mention of four of the five children of his brother Edward; Henry, Edward, Jane and Margaret and to his sister ‘Eyre’ who was occupying his house in Galway.[xix] At his death on 22nd April of 1685 his two sons were married. John, the eldest son and heir, was married to Margery, daughter and co-heir of Sir George Preston of Craigmiller, Scotland while Samuel married as his first wife his cousin, Jane, daughter of Edward Eyre of Galway.[xx] Anne, his youngest daughter, was unmarried at the time of her father’s death. She later married one Richard St. George.[xxi] Eyre’s widow, Mary Bigoe, would later marry as her second husband one John Seymour of the City of Dublin, Esq., (and later of Ballyknocken, King’s County) their marriage licence being granted three years after her first husband’s death. John Eyre the elder was buried at the small Protestant parish church which his Funeral Entry in Ulster’s Office stated he had caused to be built near his residence of Eyrecourt. His burial there would appear to be corroborated by the fact that both his widow and her second husband directed in their respective wills of 1714 and 1700 that they be buried in the same ‘parish church of Donnought near Eyrecourt.’[xxii]

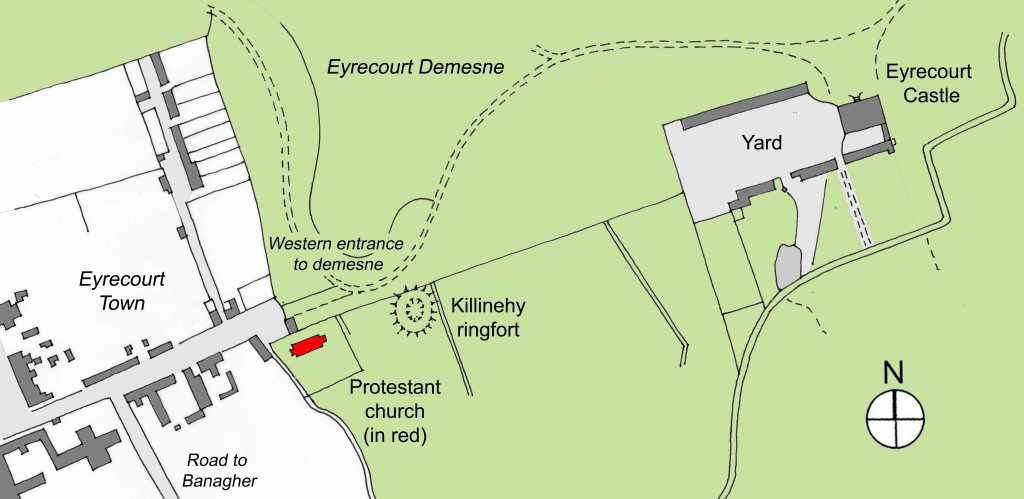

Location of the 1677 Protestant church (in red colour) at Eyrecourt in the mid-nineteenth century, wherein numerous members of the Eyre family were buried and wherein Captain John Eyre, his widow and her second husband directed their bodies be buried.

John Eyre (the younger) of Eyrecourt 1685 to 1709

Charles II was succeeded on the English throne by his brother, the Roman Catholic King James II, in 1685. The accession of a Catholic king caused great anxiety among the Protestant community, while the Irish Catholics heralded the arrival of the new king as the redeemer of their lost estates and power, their first glimmer of hope after decades of despair and frustration. Influenced in part by some of his Irish favourites at court, laws oppressive to Catholicism were relaxed by the king, and it appeared that Catholics could once again be appointed to positions of power in the realm. Concern was such with the shifting balance of power that a group of Protestants rose up in England against King James, under the Protestant Duke of Monmouth. The rebellion was crushed and those responsible were dealt with in a brutal manner.

The rising in England had repercussions also for the heir to the Eyrecourt estate of John Eyre. Born in or about 1659, John Eyre the younger was educated at Kilkenny by one Mr. Jones. Having spent about a year at Trinity College Dublin about 1675, the young John Eyre was in England when his father died in April of 1685.[xxiii] On his return to Ireland he found himself the subject of rumours, claiming that he had been hanged for participating in Monmouth’s rebellion. In addition, it was alleged his brother was ‘in the head of three score and ten horse, for Ye Duke of Munmouth’s use’. The source of the rumours, he discovered, was his father’s former agent, John Horan. The agent denied being the source, claiming it to have been another individual whose identity he could not reveal. John Eyre’s brother brought the matter before the courts and Horan was indicted for ‘scandalous words and spreading false news’. Though he admitted his guilt, Horan was acquitted; the jury believing the rumours were not intended as malicious. John Eyre appealed to the Duke of Ormonde for advice. Horan, he claimed, was now intent on ruining him and his family and believed he would swear to anything to bring about Eyre’s demise. Behind Horan’s actions, he further claimed, was a debt of five hundred pounds owed by the agent to Eyre’s father, and for which John Eyre was at that time suing Horan. With the political tide turning in the country, Eyre, with his family, fled Eyrecourt and sought the relative safety of England.[xxiv]

King William and Queen Mary

Alarmed by the increasing Catholic influence and at the birth of a Catholic heir to the king, the still powerful Protestant interest in England deposed King James, and offered the crown to his Dutch son-in-law, the Protestant Prince William of Orange and his wife Mary. The English Parliament declared James’ throne vacated in December 1688 and his daughter and son-in-law jointly crowned King William III and Queen Mary II. The Irish Catholics rose up in support of King James, and an army was sent by the French King to reinforce James’ Irish supporters, the Jacobites.

In March 1689 James landed in Ireland to head his army here, hoping to regain his throne through Ireland and a Catholic-dominated Parliament was set up in Dublin. The Irish Catholics hoped to recover much of their former lands that they were denied under the settlements after Charles II had been restored and the Irish Parliament declared many of the Williamites, supporters of William of Orange, outlaws and their lands were to be confiscated as such. King William arrived early in the following year with his Dutch and English army, and so began the war of the two kings.

The leading Roman Catholic families responded enthusiastically to the cause of James II and six regiments were raised for the king in 1688, four of which remained active throughout the war; those of the Earl of Clanricarde, his brothers Colonels Lord Bophin and Lord Galway and that of Dominick Browne.[xxv] The officer’s ranks in the Galway regiments were swelled with members of the most prominent Catholic county families.

Both John Eyre and his brother Samuel supported the cause of William and Mary, with both reputedly serving with the rank of Colonel in the Williamite army.[xxvi] During the war various detachments of the Jacobite army were stationed at Eyrecourt and at the nearby Shannon defences at Meelick, Banagher and Portumna. It would appear that no significant damage was done to Eyre’s property at this time with no reference was made to any such damage in the diary of Captain John Stevens, an English Jacobite officer serving in Ireland, who passed by Eyre’s house on his way to the battle of Aughrim. From his description of the house as ‘a pretty gentleman’s seat’ and pleasant, although ‘nothing answerable to what fame reports’ it would appear to have been intact at that time.

The aftermath of the Jacobite-Williamite War

The war concluded with the defeat of the Jacobite army and the signing in October 1691 of the Treaty of Limerick.

Many prominent Irish Jacobite faced the prospect of losing their lands under the new government of King William and Queen Mary. The estates of those deemed outlaws and traitors in February 1688 were to be vested in thirteen Trustees and the same estates to be sold.[xxvii] A large number, however, were eligible to benefit from the ‘articles of Limerick and Galway’ that formed part of the Treaty. The terms of the treaty allowed the Jacobite soldiers and people holding out at Limerick and at Galway to either sail for France or remain in Ireland and submit to the new King. Those who submitted to the new Protestant King and Queen and were eligible to benefit from the articles were to be allowed to keep their estates intact and, if outlawed, pardoned. The hearing of cases of those seeking to avail of the articles was a prolonged affair, extending into 1699.[xxviii]

Any person with a claim to lands vested in the Trustees were to present their case before the Trustees before 10th August 1700, (and later extended to 25th March 1702.) The remainder of the forfeited estates not restored by the extended deadline were to be sold before 25th March 1702 (extended to 24th June 1703.)[xxix] The confiscated estates were to be sold only to Protestants, to secure the future of a Protestant dominated island, and the money raised from which sale to be used to pay those who had fought for King William and those who had supplied the army in Ireland.[xxx]

In Galway few were finally declared outlaws and the total acreage of confiscated Jacobite lands totalled only 13,000 acres. Several notable Catholic county families managed to retain part of their estates under the articles, and so was maintained in Connacht, unlike the other three provinces, a vestige of Roman Catholic gentry, who remained locally influential, side by side with the large Protestant landowners.

There were only fourteen purchasers of these confiscated Jacobite Galway estates, and included among these was John Eyre of Eyrecourt. John Eyre’s brother Captain Samuel Eyre was still resident at Eyrecourt in 1696 but established himself after the war about Kiltormer, being described in 1704 as ‘of Newtown,’ (ie. the modern denomination of Newtowneyre) where his descendants would reside into the late twentieth century. He went on to become a Member of Parliament for County Galway and founded the Eyre family of Eyreville.

Acquisition of forfeited Jacobite lands

John Eyre was among those claiming various interests in the parcels of the vast Clanricarde estate that had been declared forfeit through the outlawry of the heir to those lands, John Burke Colonel Lord Bophin. Eyre claimed interests in lands through various leases, etc. at Lisduane, Collakearne, Gortnakelly and elsewhere, all within a short distance from Eyrecourt and at Carrowmore and elsewhere in the barony of Loughrea.[xxxi] Bophin would later have his outlawry reversed and succeed to the Clanricarde title on the payment of a substantial fine and through conforming to Protestantism and agreeing to have his two eldest sons reared in that religion.

Edward Eyre claimed lands and an annuity from the estate scheduled for forfeiture at Monivea of Patrick French.[xxxii]

Among those whose lands were subject to forfeiture within a short distance from Eyre’s mansion was Teige Daly of Killevny. His father, Hugh, had been transplanted in the Cromwellian period to Killevny and after the restoration and subsequent the Act of Settlement Teige Daly was confirmed lands in the parish of Clonfert, in Killevny, Ballyhoose, Gortacarde and Clonesease and in the adjoining parish of Donanaghta in the townland of Carrowkeanagh.[xxxiii]

The family were active Jacobites but Teige died in 1691. He was described at his death as ‘of Ballyhouse and Killevany’ and was buried ‘with his ancestors in Kilconnell abbey.’[xxxiv] At least two of his sons, however, were among those outlawed; John and Edmund Daly of Killevny.[xxxv] In the wake of the Jacobite defeat in Ireland three of Teige’s sons were among those ‘wild geese’ who sailed for France to join the French army and carry on the struggle. A large part of Teige’s estate about Killevny and Ballyhoose was declared forfeit and vested in the Trustees.[xxxvi]

With three of his sons abroad, his lands about Killevny and Ballyhoose were declared forfeit and confiscated. John Eyre’s father had already acquired the quarter of Bodellagh, Gortlehiny and other lands about Eyrecourt from Teige by mortgage and otherwise about 1675.[xxxvii] In the Court of Claims John Eyre the younger claimed the estate formerly that of Hugh and Teige Daly about Ballyhoose and Killevny.[xxxviii] The lands in question amounted to 247 profitable Irish acres in ‘Killevney, Ballycouse, Carrownekeeney and Gortcharda’ that had been mortgaged by Laughlin’s father and grandfather to John Eyre the elder.[xxxix] These lands were sold at Dublin as a forfeited estate about 1702 or 1703 and purchased by John Eyre.

The Penal Laws

Among those laws enacted in the first decades of the eighteenth century, a Roman Catholic landholder would have to divide his estate equally among his sons, that his sons might be insignificant holdings, unless one of his family should convert to the established Protestant Church, whereupon he would be entitled to lay claim to all of the estate. Formal Catholic education in Ireland was forbidden by the Penal laws, as was the sending of children of wealthy families overseas to be educated as Roman Catholics. Restrictions would be placed on Catholics in almost every field, with priests being required to register in the parish which they served and could not transfer from there. Catholic ordinations were prohibited to ensure that in a matter of time there would be no priests to serve the Catholic congregation and no priests were permitted to enter the country. Informants for the Government went about, maintaining surveillance on the clergy’s activities and rewards were offered for the priests capture, forcing many to travel in disguise and under false names.

Many of the Penal laws were in practice impossible to implement but the administration and their more zealous officials still strove to enforce these measures, thereby drawing the general population closer to their clergy and devoted to their religion.

Those of Protestant religions other than the Church of Ireland often encountered opposition from the established church as they sought converts to their particular faith. As early as 1700 a small band of Quakers travelling the country preaching their faith fell foul of John Eyre on their arrival in Eyrecourt. Their small peaceful gathering in a local barn was interrupted by a group led by Eyre, in the company of a lawyer, a constable and wardens. On Eyre’s command, the principal preacher, a man of seventy three years, was put in the village stocks, only to be joined later by two more of his colleagues before their eventual release and departure from the village later that night.[xl] It would not be until 1719 that those Protestant non-conformists such as the Quakers would be extended a degree of legal toleration.

John Eyre married twice. His first wife, Margery, died at a young age and he married secondly Anne, daughter of William Hamilton of Lisclooney and widow of Matthew Lord Louth.[xli] He had two sons and two daughters; George, John, Mary and Elizabeth. The former daughter married Rt. Hon. George Evans of Caherass, while the latter, depending upon which source is given credence, married Richard or Frederick Trench of Garbally (Ballinasloe).[xlii] John Eyre died in 1709 and was succeeded by his eldest son George.

George Eyre of Eyrecourt 1709 to 1711

George Eyre, married to Barbara, daughter of Lord Coningsby, succeeded to the estates of his father but did not live long to enjoy the fruits of the same.[xliii] He died in 1711 leaving an only child, a daughter Barbara and the estates passed to his younger brother John.[xliv]

John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1711 to 1741

John Eyre married Rose Plunkett, daughter of Lord Louth and inherited the family lands within two years of his father’s death.[xlv]

Dispute over Daly lands

The family of Teige Daly contested the Eyre’s acquisition of their father’s lands and a protracted case appears to have carried on in the courts from their sale as forfeited lands. Teige Daly’s fourth son Laughlin attempted to recover his father’s estate by proceedings in Chancery, taken against John, Samuel Eyre and Rev. Giles Eyre, Thomas Willington and Anne Lady Baroness of Louth.[xlvi]

The High Court of Chancery in Ireland found in favour of Laughlin Daly in 1719. John Eyre lodged an appeal in England by January of 1720 against the decree dated 16th June 1719 of the High Court of Chancery in Ireland, seeking that the 1719 decree be reversed.[xlvii] The appeal was protracted, with Daly on at least one occasion unable to appear and his agent, John Burke, awaiting papers of Daly’s to arrive from Ireland and the proceedings thereby delayed.[xlviii] The appeal case of ‘Eyre versus Daly’, however, was eventually decided in May of 1730 in favour of Eyre.[xlix]

John Eyre had at least two sons, John and Giles.[l] He died in 1741 and was succeeded by his son John.[li]

John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1741 to 1745

This John Eyre married in 1742 Jane Waller of Castle Waller in County Limerick. Burke’s ‘Landed Gentry’ state that he had an only child, John, who predeceased him, dying in 1743, while Rev. Hartigan states that he had a daughter Jane, who died young.[lii] (Hartigan, however, gives this John Eyre as younger than his brother Giles.) John Eyre died in 1745 and without a male heir the Eyrecourt estates passed to his younger brother V. Rev. Giles Eyre, Dean of Killaloe.[liii]

Rev. Giles Eyre of Eyrecourt 1745 to 1757

Giles Eyre of Eyrecourt pursued a career in the Church of Ireland, serving as Dean of Killaloe, Archdeacon of Ross and Chancellor of Cork. Gantz gives him as a third son of John Eyre the younger and Margery Preston and born in 1690, while Burke’s ‘Landed Gentry’ gives him as a younger son of that John Eyre of Eyrecourt who died in 1741 and Hartigan as the elder of the two sons of that John who died in 1741.[liv]

This Dean Eyre was said to have resided at Eyrecourt Castle prior to succeeding to the property, his elder brother John said to have preferred living in Dublin.[lv] The Dean was also said to have provided many of the books in that house, the preceding occupiers not having been inclined to scholarly pursuits.

The development of the village of Eyrecourt

By the mid eighteenth century the village of Eyrecourt was exhibiting a distinct loosely planned ‘urban’ shape. The basis for a long narrow market square off the villages main street appears to have been laid out by that time, as its principal focal point, a five bay two storied Market House was constructed by 1749. Another municipal building erected by that time was the village Courthouse, essential for the administration of justice and preservation of the peace locally.[lvi] Both of these two prominent public buildings served also to announce to the Eyre’s peers the family’s munificence and taste, while providing a focus for further private development within the village for their tenants. As the country began to enjoy a period of relative peace when compared with the turbulent years of the previous century, the village began to enjoy a period of relative prosperity.

The ruins of the classically-designed mid eighteenth century market house, on Market Street, in the village of Eyrecourt, which served various other uses over succeeding centuries, including use as a courthouse, schoolhouse and theatre, prior to its accidental burning in the twentieth century.

A thriving linen industry emerged, both in Eyrecourt and in Lawrencetown, as it did in many centres throughout the country. As one of the few Irish industries excluded from import duties on goods sent to England, linen manufacturing flourished in the latter half of the century. In Eyrecourt, the company of messers Wakefield, Coates, Crump and Dawson grew to become the third largest linen manufacturer in county Galway by 1761.[lvii] For landlords such as the Eyres and the Lawrences, the income their tenantry derived from the trade only led to the increased prosperity and viability of their estates.

The village’s main street terminated at the western gates to Eyre’s Demesne and the small Protestant church, constructed by the first of the family to settle at Eyrecourt. (The Demesne grounds were improved at some point, when the old public road that ran by the front entrance door of the castle, was rerouted, forcing the traveller coming from the east to travel the southern perimeter of the Demesne before entering the village. (A high stone wall following the southern perimeter of the demesne was later constructed in the mid nineteenth century during the Great Famine.)[lviii] The planned nature of the Demesne, which extended out to the village, focussed back on the Castle as the epicentre of an ordered environment, presided over by the Eyre family.

Immediate family of Dean Eyre

Dean Eyre was married to Mary, daughter of Richard Cox, eldest son of one Sir Richard Cox, bart., and a granddaughter of Sir Richard Cox of Dunmanway, one time Lord Chancellor of Ireland.[lix] His wife died about five years before her husband succeeded to the family estates. Dean Eyre died in 1757, leaving two sons, John and Richard, the eldest of who inherited the Castle and estates.

John Baron Eyre of Eyrecourt 1757 to 1781

John Eyre of Eyrecourt, the Dean’s son, was created Baron Eyre of Eyrecourt in 1768. An avid follower of cockfights, his lifestyle was similar to that of many of his Irish peers and contemporaries, and was described to a degree by the son of his friend and neighbour, Bishop Cumberland of Clonfert. Having accompanied Eyre to visit a friend, Cumberland recalled Eyre on that occasion as being, ‘though pretty advanced in years,…so correctly indigenous as never to have been out of Ireland in his life, and not often…far from Eyrecourt. Proprietor of a vast extent of soil, not very productive, and inhabiting a spacious mansion, not in the best repair, he lived according to the style of the country, with more hospitality than elegance, and whilst his table groaned with abundance, the order and good taste of its arrangements were little thought of. The slaughtered ox was hung up whole, and the hungry servitor supplied himself with his dole of flesh sliced from off the carcase.’

‘His lordship’s day was so apportioned as to give the afternoon by much the largest share of it, during which, from the early dinner to the hour of rest, he never left the chair, nor did the claret ever quit the table. This did not produce inebriety, for it was sipping rather than drinking that filled up the time, and this mechanical process of gradually moistening the human clay was carried out with very little aid from conversation, for his lordship’s companions were not very communicative, and fortunately he was not very curious.’[lx]

John, Lord Eyre of Eyrecourt, married Eleanor, the daughter of James Staunton of Galway, and had, by her, an only child, Mary. Mary married James Caulfield, son of Lord Charlemont, but both Mary and her husband were drowned, together with their young infant, in 1775, when their ship sank in a hurricane between England and Ireland.[lxi]

Portrait described by Rev. A.S. Hartigan in his history of the Eyre families of Eyrecourt and Eyreville as that of ’Richard Eyre M.P., brother of Lord Eyre. There is a marked similarity, however, between this portrait and another described in the same publication as that of Rev. Richard Eyre LLD, son of Richard and Anchoretta Eyre of Eyrecourt. (c) N.L.I., Dublin.

John Lord Eyre died six years later and with no male heir, his title expired also. Following his death in 1781, the senior-most lines of the Eyres of Eyrecourt were determined in relation to their descent from his only brother, Richard Eyre M.P., whose eldest son, Colonel Giles Eyre of Eyrecourt was Lord Eyre’s eldest nephew and heir, and who succeeded his uncle at Eyrecourt Castle. From this Colonel Giles Eyre descended the senior-most line, while from Richard’s second son, Rev. Richard Eyre D.D. of Eyrecourt, derived the second line, from the third son of Richard Eyre M.P., Brigadier General Thomas Eyre, descended the third line and from the fourth son, Captain John Eyre, the fourth line.

Continued at ‘Eyre of Eyrecourt Part II’

[i] The funeral certificate of Captain John Eyre of Eyrecourt, Co. Galway being the seventh son of Giles Brickworth in Co. Wilts and Jane Snellgrove of Radlinch, Co. Wilts with account of their children and grandchildren, April 22 1685. (NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 87, pp. 75-9 & 115.)

[ii] Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, pp. 88-115.

[iii] Hartigan, Rev. A.S., A Short Account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Reading, n.d.

[iv] Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, pp. 88-115.

[v] Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, p. 93.

[vi] NLI, Dublin, G.O., Ms. 73 Funeral Entries, p.73. Funeral Entry of Phillip Bygo of Newtown in the King’s County.’ Bigoe married firstly Susanna, daughter of another Bigoe and secondly Bridget, daughter of Sir George Herbert, Bt. He was survived by two daughters, Mary, wife of John Eyre and Catherine, married to Gilbert Rossan of Dorra.

[vii] Family and estate papers of the Eyre family of Eyreville, Co. Galway, in possession of author. Bond between John Eyre of Clonfearte in Countie Galway Esquire and Sir Thomas Esmonde of Claddagh in the halfe Barony of Ballamoe and Countie of Galway Esquire relating to lands in the parishes of Dononaghty and Clonfertt, Barony of Longford and Countie of Galway dated 3rd September 1656; Bond between John Eyre of Clonfearte in Countie Galway Esquire and Laurence Esmonde of Claddagh in the halfe Barony of Ballamoe and Countie of Galway Esquire relating to lands in Barony of Longford and Countie of Galway dated 15th October 1657.

[viii] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p 115. Ida Gantz gives Edward as younger than his brother John Eyre, but Burkes Landed Gentry give Edward as the sixth son of Giles of Brickworth; Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, pp. 88-115.

[ix] Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, pp. 88-115.

[x] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, pp. 113-4. The same portrait was said to have been later lost at sea when being brought to London for repair.

[xi] Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, pp. 88-115.

[xii] Ballyhugh, 2km east of the village of Eyrecourt, and 3.5 km north of the Meelick friary, together with the townlands of Killine, Rath, Corragh, Claggernigh, Gortnaskemore and Clonesmucke, as a group in the early seventeenth century, constituted the later larger townland of Abbeyland Great, par. of Clonfert. Ballyhugh, at least, continued as a local placename within Abbeyland Great into the early twenty first century. Kilaltenagh and the adjacent larger townland of Kilmacshane, par. of Clonfert, are situated 6km to the north east of the Meelick church.

[xiii] Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, p. 103.

[xiv] NLI, Dublin, Ms. 3268, Seymour of King’s Co., Co. Galway by H. Seymour Guinness. Genealogical Notes with Pedigree Table relating to the Seymour family. Ida Gantz in her 1975 publication ‘Signpost to Eyrecourt’ asserted that it was believed Eyre initially resided at Clonfert Palace. The genealogical notes relating to the Seymour family by H. Seymour Guinness show that John Eyre resided at Ballymore in 1667 and 1668. John Eyre was described as ‘of Bellimore, County Galway, Esquire’ in a deed involving Redmond Morris of Collrosse, Co. Tipperary dated 10th January 1665 among the family and estate papers of the Eyre family of Eyreville, Co. Galway.

[xv] 15th Annual Report of Records of Ireland, p. 358.

[xvi] Among the earliest buried there, with the exception of the Eyre family, were Henry Canneville, who died in 1719, at the age of 90 years and James Banco, who died, aged 74 years, in 1722. Their age would point to these men as having been among the first of a minor class of Protestants who settled in and about the village in the mid to late seventeenth century.

[xvii] Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, p. 107.

[xviii] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 35, p.89

[xix] NLI, Dublin, Ms. 3268, Seymour of King’s Co., Co. Galway by H. Seymour Guinness. Genealogical Notes with Pedigree Table relating to the Seymour family; Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, pp. 88-115; NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 87, Draft Grants E, c. 1630-1780, pp. 75, 115.

[xx] Hartigan, Rev. A.S., A Short Account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Reading, n.d.

[xxi] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, pp. 127-8; Cronin, J., A Gentleman of a good family and fortune: John Eyre of Eyrecourt 1640-1685, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 60, 2008, pp. 107-8.

[xxii] NLI, Dublin, Ms. 3268, Seymour of King’s Co., Co. Galway by H. Seymour Guinness. Genealogical Notes with Pedigree Table relating to the Seymour family; NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. 87, Draft Grants E, c. 1630-1780, pp. 75, 115; Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975,, pp. 127-8

[xxiii] Hartigan, A.S., History of the Family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville, Part II, London, M.M. Taylor & Co., 1904, p. 69, Trinity College Matriculation Registers, 1675-1837; Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, pp. 122, 128.

[xxiv] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, pp. 128-130.

[xxv] Mulloy, S., Galway in the Jacobite War, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 40, 1985-6, pp. 3-4.

[xxvi] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975,, p. 131; Hartigan, Rev. A.S., A Short Account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Reading, n.d.

[xxvii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. xix.

[xxviii] Simms, J.G., Irish Jacobites, Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, 1960, pp. 14-5.

[xxix] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. xix.

[xxx] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. xix.

[xxxi] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 141, no. 1321.

[xxxii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 69, no. 639.

[xxxiii] Both he and his wife were commemorated by a stone tablet that was affixed to the north wall of the Meelick friary church; ‘D:Thaddaeus Daly de Killevny sibi, dilectae conivgi Dorotheae Hearne, ac posteris suis hoc monumentum erigi fecit. Die 13 Iuny 1682.’

[xxxiv] C. ffrench Blake-Forster, The Irish Chieftains or A struggle for the crown, 1872.

[xxxv] Analecta Hibernica No. 22, I.M.C. 1960, pp. 71,72

[xxxvi] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 144, no. 1341.

[xxxvii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 144, no. 1341.

[xxxviii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 144, no. 1341.

[xxxix] MacLysaght, E., Dunsandle Papers, Analecta Hibernica No. 15, IMC, 1944, p. 405.

[xl] J.G.A.H.S. vol. 36, 1977-8.

[xli] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p. 132.

[xlii] Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388; Sir B. Burke, A genealogical and heraldic history of the Landed Gentry of Ireland (rev. by A.C. Fox-Davies), London, 1912, p. 700.

[xliii] Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388.

[xliv] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p. 151; Hartigan, Rev. A.S., A Short Account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Reading, n.d.

[xlv] Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388.

[xlvi] D’Alton, J., Illustrations, historical and genealogical of King Jame’s Irish Army List 1689 (2nd edition), London, J. Russell Smith, 1861, Vol. II, p.147; MacLysaght, E., Dunsandle Papers, Analecta Hibernica, No. 15, IMC, 1944, p. 405. The five defendants were named as such in 1724. Laughlin’s father was confirmed therein as having died in 1691.

[xlvii] Journal of the House of Lords, beginning 1726, Vol. 21, January 1720, p. 195

[xlviii] Journal of the House of Lords, beginning 1726, Vol. 23, 1728, p. 328, In the case of ‘Eyre versus Daly’, ‘Upon reading the petition of John Burke, Agent for Laughlin Daly, Respondent to the Appeal of John Eyre Esquire, praying ‘that the hearing of the said cause which stands for Tuesday next may be put off to such time as this house shall think fit, the Respondents papers not being yet come from Ireland.’

[xlix] Journal of the House of Lords, beginning 1726, Vol. 23, May 1730, p. 572. ‘Upon hearing counsel, as well yesterday as this day, upon the petition and appeal of John Eyre Esquire; complaining of a decree of the Court of Chancery in Ireland, made the sixteenth day of June 1719, in a cause wherein Laughlin Daly, Gentleman, by Original and Supplemental Bill, was plaintiff and John Eyre Esquire and others were defendants; and praying ‘that the said decree be reversed. As also upon the answer of the said Laughlin Daly put in to the said Appeal; and due consideration had of what was offered on either side of this cause: It is ordered and adjudged by the Lords Spiritual and Temporal in Parliament assembled, that the said decree complained of in the said appeal, be, and is hereby, reversed; and that the Original and Supplemental Bills, exhibited in the said Court of Chancery by the said Respondent, be, and are hereby, dismissed.’

[l] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p. 151; Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388.

[li] Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388.

[lii] Hartigan, Rev. A.S., A Short Account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Reading, n.d.

[liii] Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388.

[liv] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p. 151; Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388; Hartigan, Rev. A.S., A Short Account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Reading, n.d.

[lv] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975,, p. 151.

[lvi] Gantz suggests that the Courthouse dated from the time of the first John Eyre of Eyrecourt. (Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p. 150.)

[lvii] Cronin, D.A., A Galway gentleman in the age of Improvement; Robert French of Monivea, 1716-79, Irish Academic Press, 1995.

[lviii] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p. 206.

[lix] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, p. 151; Burke, J. and Burke, J.B., A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, London, Henry Colburn, 1847, Vol. I, A-L, p. 388.

[lx] Hartigan, A.S., A short account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Dublin, 1904.

[lxi] Hartigan, A.S., A short account of the family of Eyre of Eyrecourt and Eyre of Eyreville in the County of Galway, Dublin, 1904.