© Donal G. Burke 2014

Kilmalinoge lies within the barony of Longford in the east of County Galway, what was for the most part the territory of Síl Amnchadha, ruled by the O Madden chieftain in the late medieval period.

The ruins of the late medieval church of Kilmalinoge lie in the west of the parish of the same name, on a slightly elevated rural site overlooking a somewhat flat landscape of good agricultural quality. It is surrounded by a small graveyard, the earliest surviving headstones of which are located on the south side of the church and date from the eighteenth century, although burials were recorded here from a much earlier period. The landscape in the immediate vicinity of the churchyard undulates and aerial photography would suggest the presence of a wider enclosure irregular in plan surrounding the church and its modern graveyard.

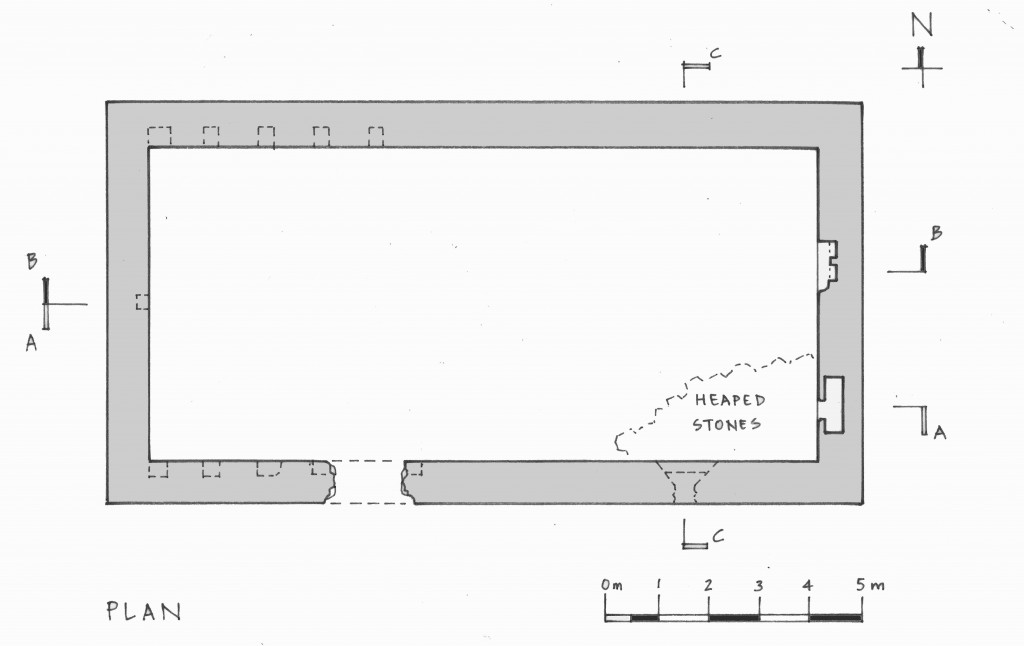

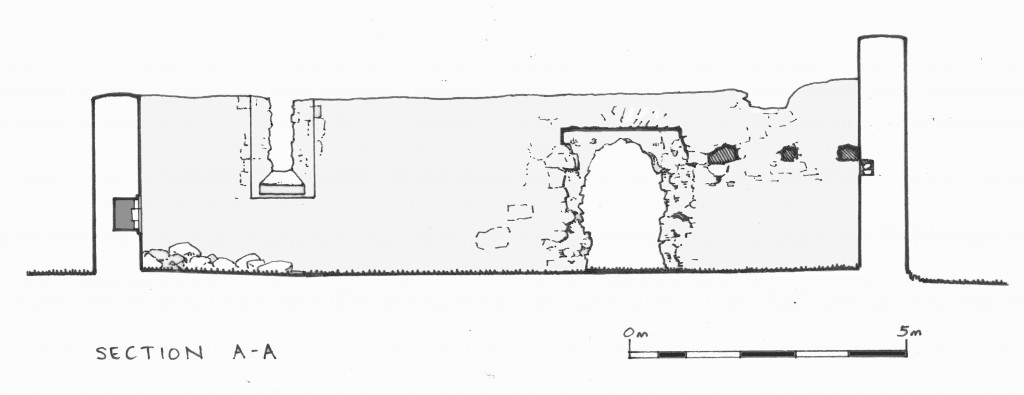

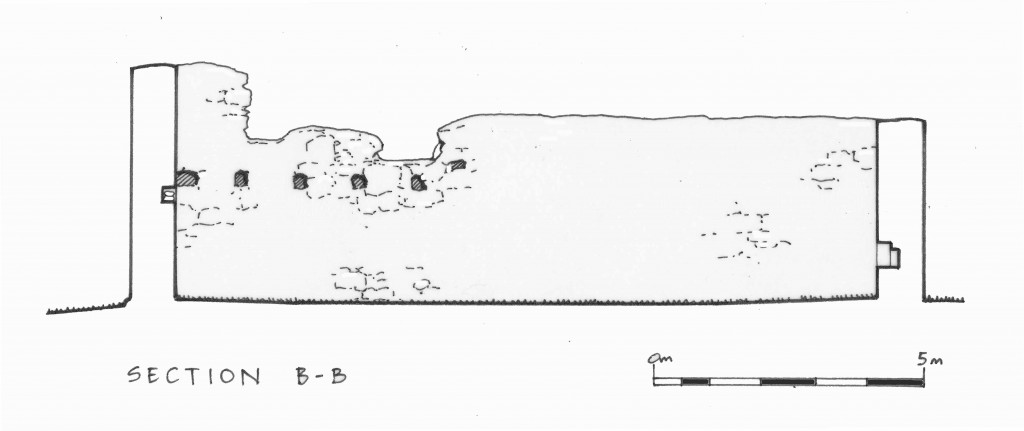

The church itself lay in ruins by the early nineteenth century and remains so into the twenty-first. It is a limestone-built structure, rectangular on plan and single chambered. Small in size, it measures approximately 6.2 m wide and 13.1 m long. While essentially composed of only one space at ground level, surviving beam holes in the west gable and part of the north and south walls suggest that there was a loft or gallery over the western part of the building.

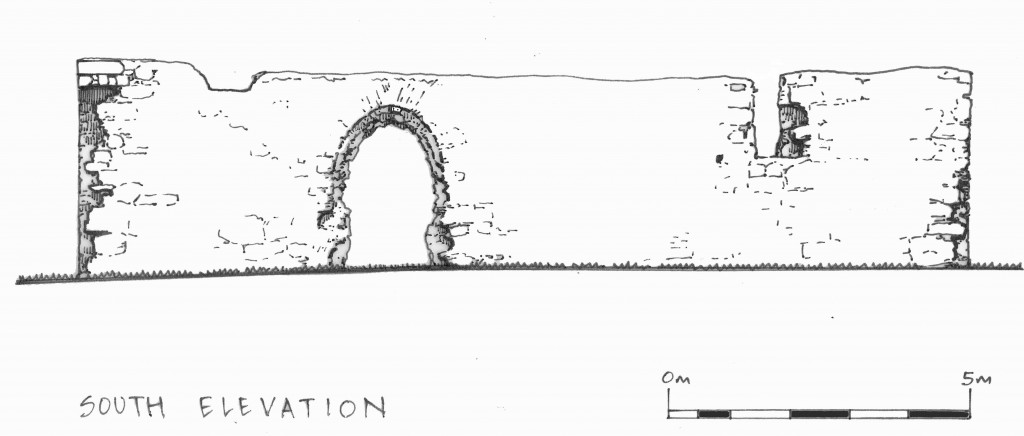

On plan the structure was oriented on an east-west axis, with the only entrance door located at the western end of the south wall. From the surviving wall structure it is possible to identify only one window with certainty, a high-level narrow slit or lancet window on the south wall with an internal embrasure, close to the east gable.

Plan of the late medieval church at Kilmalinoge by the author. Burial plots and headstones have been omitted from the plan and sections for clarity.

South elevation of Kilmalinoge church by the author. The trace of a possible high level window appears to be discernible to the left of the doorway.

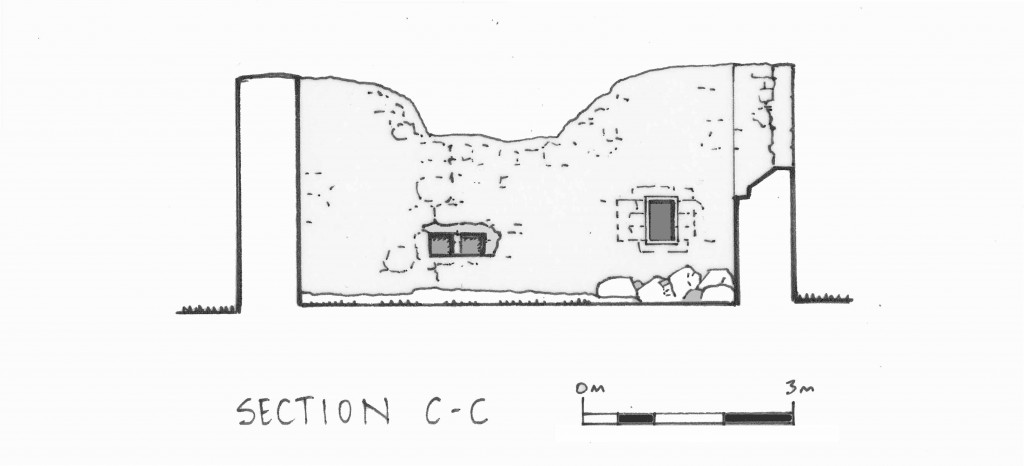

Sectional views of Kilmalinoge church by the author. The location of the loft floor-beam holes suggest that the timber door may have been lower than the existing damaged structural opening.

In November of 1838 the antiquary John O Donovan visited the parish of Kilmalinogue when gathering information on the antiquities of the county. At that stage the pointed-arched doorway had been already badly damaged to the extent that he was unable to determine its original width. ‘The chiselled stones have been picked out of it’ he wrote ‘with the exception of two which form the apex, from which it appears that it was well built and ornamented.’[i] The illustration of this apex piece that he provided for his correspondent differs slightly from the only now surviving stone apex piece but it would suggest that one of the two pieces had disappeared in the intervening period. The surviving quoin stones at each of the four external corners are finely cut and finished but, as appears to have occurred with the doorway, the majority of the stones, in particular those closest to ground level, have been removed.

South elevation of the church showing the damaged doorway (above) and surviving apex stone (below)

Although no clear trace of a window in the east gable was discernible by the twenty-first century, O Donovan’s statement that ‘the window in the east gable is totally destroyed and the west and north side wall are featureless’ would suggest that there was evidence at that time of a window in the east gable at one time. He also remarked on the remains of two small windows ‘now nearly destroyed in each side wall to light the upper room.’ [ii] The only evidence in the twenty-first century of any small windows at high level in the south and north walls to light this loft would appear to be a slight depression in wall height at both locations.

South-West corner of the church

North-East corner of the church

North-West corner of the church

The surviving slit window on the south wall, near the eastern gable, also suffered damage at some stage after O Donovan’s visit. In the early nineteenth century O Donovan described this window as ‘in the round large (wide) lancet style, perfect inside but destroyed on the outside with the exception of two stones at the top which are chiselled and ornamented.’ His accompanying sketch shows a chamfered stone round window head and an associated stone below. This round window head was removed when stones from the external walls were taken away and the walls reduced in height. A rough layer of cement was simultaneously applied to the top of the walls.

O Donovan did not give a height for the external walls but they were reduced in height in the early years of the twenty first century, the difference in height of which may be estimated from a comparison with photographs of the building dating from the early twentieth century.[iii] The ivy-clad stone wall of the south elevation at that stage was at least approximately 750mm higher than it is at present, showing the round window head stone of the slit window at the south-east end intact. Similarly the depression in the wall at high level to the west of the entrance door was more distinct in the early twentieth century and more clearly suggests the earlier presence of a high level window serving the loft area.

While the original height of the external walls is not clear from the surviving structure, the external walls of surviving parish churches such as that at Lackagh in County Galway were significantly higher.[iv]

Externally there is no evidence of a batter but barely-discernible low-level base stones protrude slightly beneath the west wall and exposed on the south-west corner and may have served as part of a foundation base.

Internally there are traces of a thin layer of plaster on the face of the south wall but there appears to have been few internal features of note, with the exception of two wall niches on the east wall. O Donovan refers to these as ‘two square recesses in the east gable which were evidently used for holding chalices and other things belonging to the Altar.’ Neither has a drainage hole and as such may not have served as a piscina proper.

Internal face of east gable (above) and of west gable showing hole for support beam (below). This support beam would appear to have served to break the span of the loft floor beams and may have required a timber post in the centre of the nave in front of the entrance door.

Within the walls of the church the ground level is uneven and are several headstones dating from the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A small build-up of rubble and stone has been heaped in the south-east corner within the church and the ground level is slightly higher at this point and against the internal face of the east gable where possible early high-status burials may have occurred, in close proximity to the altar.

O Donovan remarked on what was a ‘very large ash tree in this Churchyard opposite the south side wall, extending its nine aged arms far and wide. The largest one of these arms’ he wrote ‘has been prostrated to the ground by a storm but it still retains its vitality and will soon strike an independent root for itself.’ [v] The tree, the largest he had witnessed in any churchyard in his progress across the country at that time, did not survive into the twenty-first century.

The remains on site of a fragment of what may have been a late medieval or modern gravestone cross.

The late medieval period

During the papacy of Pope Paul II in the latter half of the fifteenth century, one Thady Ohayatan (O Hanrahan), canon of the monastery of St. Mary de Portupuro, Clonfert, O.S.A. complained to the Papal authorities that Culaus Omaeladuni, perpetual vicar of the parish church of Cillmulonog (Kilmalinoge) in the diocese of Clonfert had ‘openly committed fornication, even after lawful admonition, dilapidated and converted to evil uses the goods of the said vicarage of Cyllmulonog and has committed perjury.’ The Papal authorities wrote from Rome in March of 1466 directing that Culaus be ordered to appear before three individuals of the local diocese (the dean and official of Clonfert and a canon of the same) and if they found that the accusations were true, Culaus was to be deprived of the vicarage and it was to be assigned to Ohayatan.[vi]

In the late medieval period the principal landholders within the parish were a branch of the wider O Madden established about Derryhiveny in the eastern part of the parish and the O Cormicans, who provided a significant number of clerics to the Church locally over succeeding generations in the late medieval period and whose lands lay near the church in the early seventeenth century.

About 1481 Maurice O Cormican, priest, John O Cormican, clerk and William O Brogay, an Augustinian canon, were accused of detaining a canonry of Clonfert and the prebend called ‘of Kyllaiayn therein’ and the perpetual vicarage of Lickmolassy and a perpetual benefice without cure called a rectory in the church of Kyllmolonog (Kilmalinoge) and another in the church of ‘Magunacclay’ (Magheranearla) in the diocese of Clonfert. They were believed to have had one Thady O Lorcan captured and forced ‘by lay power’ to swear under oath to desist from any attempt to obtain the same canonry, positions and benefices but the Papal authorities ordered the matter to be investigated, the removal of the O Cormicans and O Brogay and to have the vicarage of Lickmolassy given to O Lorcan.[vii]

John O Cormican appears to have come to an accommodation with O Lorcan as one of that name, a clerk of the diocese of Clonfert, together with Thady O Lorcan was illegally detaining ‘the perpetual benefice without cure called the church or rectory de Madnurlay (recte: Magheranearla) and the perpetual vicarage of the parish church of Lickmolassy in the late 1480s. The detention was brought to the attention of Rome by John O Treacy, a clerk of the diocese. The Papal authorities decreed in April 1488 that the matter should be fully investigated and if the two accused were guilty, O Treacy was to be made beneficiary.[viii]

It was common in the medieval and late medieval period for parishes often to have had their priests or clerics appointed from those families whose ancestral lands lay within that parish, individuals from the family group thereby deriving the income from the benefices of that office. At the time of the Visitation of the Diocese of Clonfert in the late 1560s by the then Bishop, Roland Burke, the wider O Cormican family group provided the greatest number of clerics of any single family name to offices within the diocesan Church. At least five men of the name were then holding offices or derived benefices. Thadeus (Tadhg) O Cormacayn held the prebendary of Kilquain, Odo (Hugh) that of ‘Bennmor’, while Johannes (John) was vicar of Kyllmoconna (parish of Lusmagh), Maurice vicar of ‘Dunnochto’ (the parish of Donanaughta or ‘Eyrecourt’), Donatus (Donagh) O Cormacayn vicar of Tirenascragh parish and William O Cormacayn held the vicarage of Kilmalinoge and rectory of ‘Kenvoy.’ [ix]

Seventeenth Century landholders

Part of the lands occupied by the O Cormicans in the mid seventeenth century were Church lands which they appear to have occupied for some time. The Protestant Bishop of Clonfert claimed in 1615 that the O Cormicans were among a number of septs who detained land from the Bishop ‘by prescription’, preventing his deriving an income from the same. The Church land detained by the O Cormicans, according to the Bishop, comprised of one quarter of Lickmolassy.

The principal landholder of the Cormican name in the late 1630s, prior to the redistribution of lands in the Cromwellian period, was one Erevan mc Erevan O Cormican, whose lands lay for the most part in the western part of the parish near the church.[x] The O Cormicans lost ownership of their lands in the parish of Kilmalinoge as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century.

The church site at Kilmalinoge served as the burial place of the O Madden family of Derryhiveny. This branch of the wider O Madden family were descended from an individual named Cathal O Madden, who served as chieftain of Síl Anmchadha some time in the late fifteenth century and as a family group were significant landholders in the territory as a whole. The senior-most member of this family group, John son of Daniel son of Brasil O Madden, married to a daughter of the head of the O Horan family, died on the 5th February 1639 and was buried at the church of Kilmalinoge.[xi] While no trace remains of the Madden burial place, it is likely that this may have been located within the church and near the east gable, to the right of the altar, given their locally high status. (This John would appear to be the same man as that individual who had a chalice presented to Portumna convent in 1644 inscribed with the name of ‘Joannes Madyn de Deriheuny’ which may have been presented to comply with the last wishes of this John.)[xii]

John O Maddens’s eldest son Daniel was sufficiently wealthy to have constructed a tower house at Derryhiveny in the 1640s. Like the nearby O Cormicans, the senior line of this family lost possession of their lands about Derryhiveny as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century. Much of the lands of Killmalinoge were reserved for Henry, son of Oliver Cromwell, as part of a large estate along the Shannon from the parish of Lickmolassy to Clonfert and included the Earl of Clanricarde’s seat at Portumna, resulting in the confiscation of O Madden’s ancestral lands about Derryhiveny as part of that estate.[xiii]

It is unclear at what stage the church fell into disuse. The existence of two headstones within the church, both located beside the west gable, one dating from 1781 and another dated 1801, suggests that the building was in use as a burial site and so, in all likelihood, roofless from at least the eighteenth century if not earlier.

[i] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, pp. 21-2.

[ii] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, pp. 21-2.

[iii] Conwell, J.J., Lickmolassy by the Shannon, History of Gortanumera and surrounding parishes, published by the author, 1998, pp. 65-82.

[iv] This late medieval church is identified as St. Columbkille’s Church on nineteenth century Ordnance Survey maps and is situated in the townland of Lackagh Beg in the parish of Lackagh, near the moden village of Turloughmore in County Galway.

[v] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, pp. 21-2.

[vi] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 12: 1458-1471, London, 1955, Lateran Regesta 647: 1466-1467, p. 557.

[vii] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 13: 1471-1484, London, 1955, Lateran Regesta 813: 1480-1482, p. 764.

[viii] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 14: 1484-1492, London, 1960, Vatican Regesta 732: 1488, p. 221.

[ix] McNicholls, K.W., Visitations of the Dioceses of Clonfert, Tuam and Kilmacduagh, c. 1565-67, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, 1970, pp. 144-157.

[x] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 180-2.

[xi] N.L.I., Dublin, G.O., Ms. 146, Linea Antiqua (Betham), p. 272, 298, 299.

[xii] Egan, Rev. P.K., ‘Clonfert Museum’, JGAHS, Vol. XXVII, 1956-7, p. 47. The chalice was later presented to Clonfert Museum, Loughrea. Inscribed on the foot of the chalice was ‘Joanes Madyn de Deriheuny Moriens me fieri iussit pro Conventu portumnensi 1644.’ This chalice was noticed in a convent in County Waterford by Fr. Francis Daly of Ahascragh, Co. Galway in 1892, when giving a retreat to nuns. After the nuns consented to exchange this chalice for a new chalice, Fr. Daly presented Madden chalice to his nephew Peter Albert Daly of Ahascragh, together with a new ciborium and paten, for use in the Daly family chapel. On the sale of his house in 1927 P.A. Daly presented the chalice, ciborium and paten to his sister, wife of Count Sean D. O Kelly of Gurtray whose family, like that of the original donor, were also buried at Kilmalinoge. The chalice was later lent to the Clonfert Museum by Group Captain A. P. V. Daly of Garryannagh, Nenagh, Co. Tipperary in the mid twentieth century and in the 1990s was in the possession of Dermot Daly in Chesire, England. (Conwell, J.J., Lickmolassy by the Shannon, History of Gortanumera and surrounding parishes, published by the author, 1998, pp. 65-82.)

[xiii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. xlvii, 180-2; Simington, R.C., The Transplantation to Connacht 1654-58, Shannon, Irish University Press, for the I.M.C., 1970, p. 161.