© Donal G. Burke 2015

With the exception of the senior branches of the O Maddens, the MacCuolahans, formed one of the four main constituent families owing services and dues to the ruling O Madden chieftain in the late medieval period. Their ancestral lands at that time lay in Lusmagh on the eastern bank of the River Shannon, which formed part of the O Madden territory of Síl Anmchadha and centred about an area whose name was derived from that of the family, that of Ballymacoolaghan, the ‘baile’ (ie. ‘townland’ or ‘township’) of the MacCuolahans .

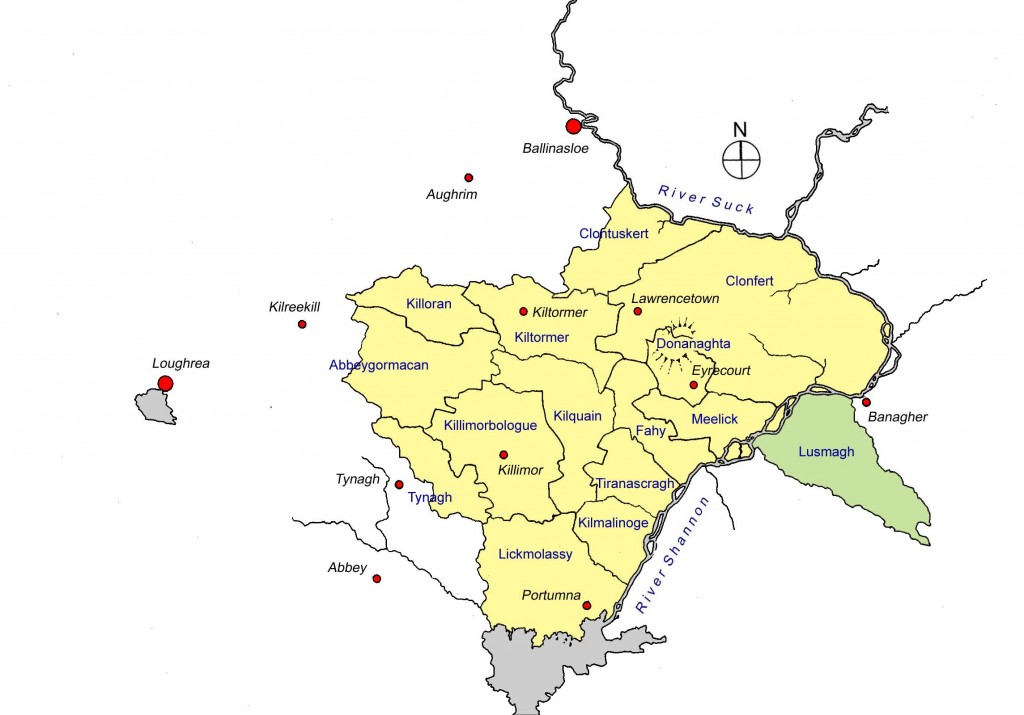

Their ancestral lands lay within the O Madden territory of Síl Anmchadha which covered the eastern-most part of the later county Galway and more specifically lay in the parish of Lusmagh. That parish formed the only tract of land of County Galway that lay on the eastern bank of the River Shannon and was only disconnected from Connacht and County Galway in the mid seventeenth century and made to form part of the county known as King’s County, later County Offaly.

Map of the early-seventeenth century barony of Longford in east Galway, formerly the O Madden territory of Síl Anmchadha, shown in yellow with the location of the parish of Lusmagh shown in green. The parish of Lusmagh would became part of King’s County (later County Offaly) in the mid-seventeenth century.

Origin

The MacCuolahan or Cuolahan family of east Galway are an offshoot of the wider Uí Maine family group, whose ancestor has traditionally been held to be one Maine mór, son of Eochaidh feardaghiall, chief of a tribe of people who established themselves as the dominant group in the south-eastern region of Connacht by about the end of the fifth century.[i]

Maine mór and his descendants appear to have subjugated many of the existing tribes and peoples that inhabited their land and established a petty kingdom, covering much of the later east Galway named from their progenitor as Uí Maine (later Anglicised Hy Many). The senior-most family descended from this Maine was the O Kellys, from whom the rulers or chieftains of Uí Maine were drawn.

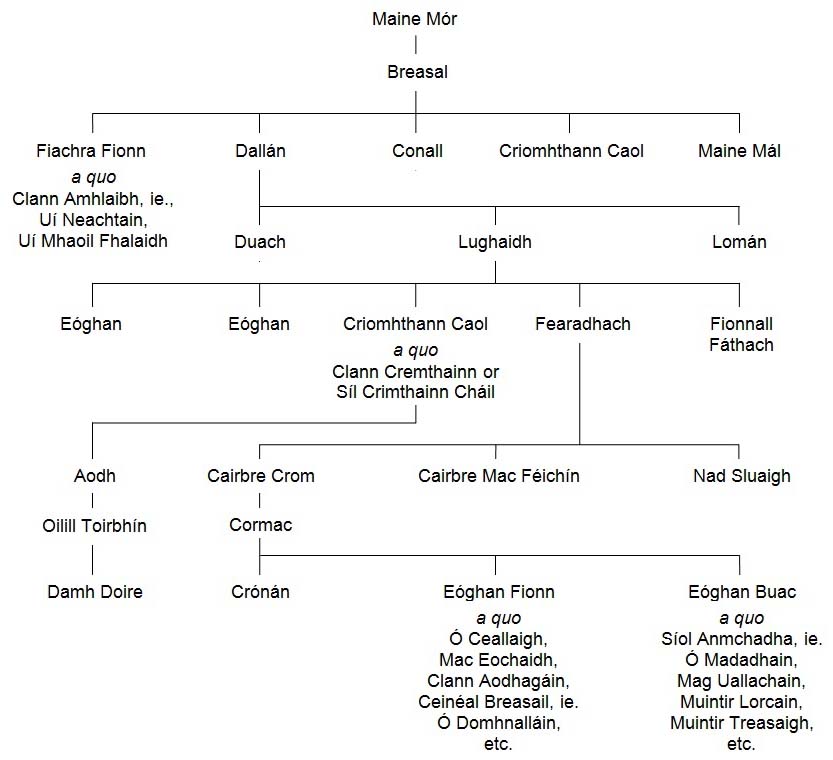

Within the greater Uí Maine kin group the MacCuolahans were part of the group of families who composed the Síol Anmchadha, the ‘seed’ or progeny of Anmchadh.’[ii] Most of the senior families of the Uí Maine claim descent from Cairbre crom, reputed to have flourished about the early or mid sixth century A.D. and to have been a fifth generation descendant of Maine mór.[iii] Anmchadh’s descent was given as his being the son of Eoghan buac, son of Cormac, son of Cairbre crom.

Pedigree of various early members of the Uí Maine, derived from Dubhaltach MacFirbisigh’s seventeenth century ‘Great Book of Irish Genealogies,’ showing the origin of Mag Uallachain or MacCuolahan in relation to that of several other prominent families of the Uí Maine.

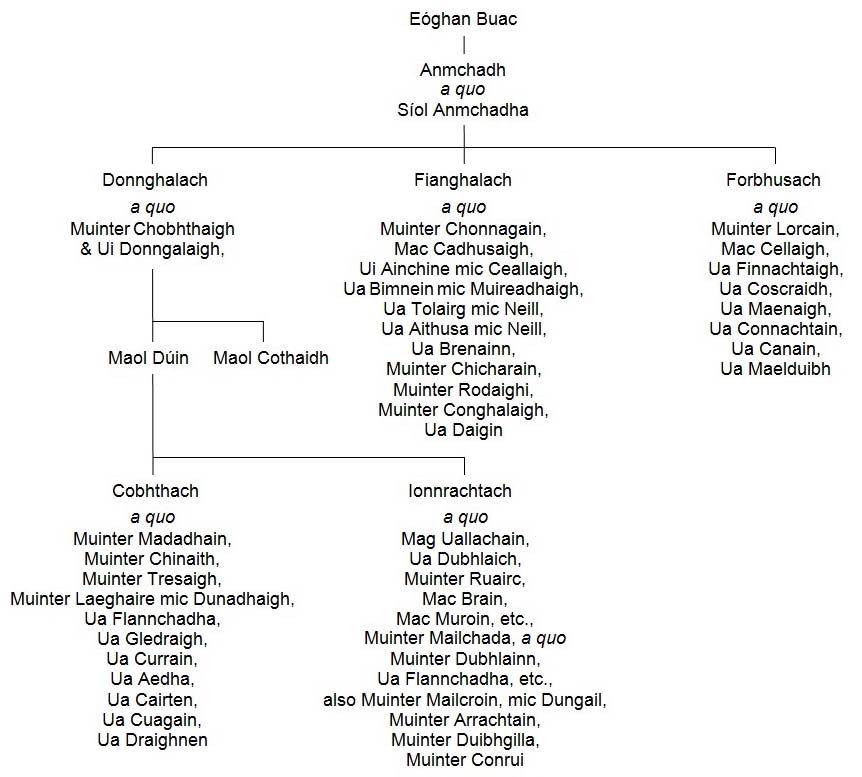

The principal family of the Síol Anmchadha family group, the O Maddens, came to rule a part of the eastern region of Uí Maine, to be known thereafter from their common ancestor as Síl Anmchadha or ‘O Maddens County’ and later as the barony of Longford in east Galway. From this same Anmchadh the group of related families descend, such as the O Maddens and others that would be collectively known as the Síol Anmchadha or ‘seed of Anmchadh’ and from whom the territory that came to be dominated by the O Maddens would be known.[iv] While the O Maddens and certain others of the Síol Anmchadha such as the Treacys were said to be descended from Amnchadh’s eldest great grandson Cobhthach, the MacCuolahan’s descent was given as derived from Uallachan, son of Flann, son of Flannchadh, son of Ionnrachtach, this last a younger brother of the same Cobhthach.[v]

Pedigree showing the descent of Mag Uallachain from Ionnrachtach son of Mael Duin and the inter-relationship of the Síol Anmchadha, derived from the Book of Lecan. MacFirbisigh’s genealogy of the Síol Anmchadha gives Forbhusach son of Anmchadh as junior to his brother Donnghalach but more senior than Fianghalach.

The nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan noted in his ‘Tribes and Customs of Hy Many’ the reference in O Dugan’s fourteenth century Topographical Poem to O hUallachain (recte: MacCuolahan) as ‘oirrigh…os urlár na n-Anmchadhach or ‘chieftain over the plain of the race of Anmchadh.’ The Book of Lecan, an early fifteenth century compilation of various other manuscripts, in giving the origin of the MacCuolahans, refers to them as the ‘sein-riga na n-Anmchadh,’ translated by O Donovan as ‘the old chieftains of Sil Anmchadha.’[vi] O Donovan considered it ‘very extraordinary’ although possible that the MacCuolahans may have been at one time chieftains of Síl Anmchadha prior to the rise of the O Maddens but, other than O Dugan’s Topographical Poem, the only reference to their being chieftains of Síl Anmchadha, would appear to have been taken to be an account of the death of Gilla finn the son of Mac Uallachain ‘King of Sil Anmchadha’ in 1101. This reference was a translation of an account of the defeat at Clonmacnoise of a family group known as the Muinter Cinaoith by another known as the Muintir Tadhgáin, in which the same Gilla finn was killed. The original reference derived from ‘Chronicon Scotorum,’ a medieval chronicle, a seventeenth century copy of which survived and the original of which did not. Given that family surnames were only beginning to be borne as hereditary by descendants of a common ancestor about the eleventh century, the translation of this individual as a MacCuolahan may have been a misreading of the text as his name in the surviving seventeenth century copy was given as ‘an Gilla Finn mac meic Uallacháin rí Síl Anmchadha’ and may have referred to one Gilla finn, a grandson (ie. ‘mac meic’ or ‘son of the son of’) of Uallachain, chieftain of Síl Anmchadha.

Similar references about this time in the Annals of the Four Masters to the raid in 1085 on the territory of Síl Anmchadha by individuals of the Conmaicne, a rival family group, in which one Coningin finn MacUallachain was killed may have been a reference to the son of Uallachain having been killed.

The death in battle in 1159 of one Aedh or Hugh son of MacCuolahan, chieftain of Muinter Cinaoith, killed in a conflict between the king of Connacht and the King of Aileach, may, however, have been an early reference to the use of MacCuolahan as an hereditary surname. This Aedh in the original Irish of the Annals of the Four Masters was given as ‘Aodh mac Mic Uallacháin, Taoiseach Mhuintire Cionaetha’ or ‘chieftain of Muintir Cinaoith.’ His identification as Aedh son of MacCuolahan would appear to be supported in this case by the reference to other surnames of Connacht in the same battle such as O Connor, O Shaughnessy and MacNevin.

A late medieval account of one of the name made reference to one Dermit Maccuolachayn, who held the perpetual vicarage of Dunnanochta in the diocese of Clonfert prior to his death before 1433. On his death the vicarage was void but was held illegally for more than two years by one Malachy O Horan, a canon of St. Mary’s (the Augustinian monastery de Portu Puro at Clonfert). The position at the vicarage of Dunnanochta was by right at that time filled by a canon of the abbey of Clonfert and the Papal authorities about 1435 ordered the removal of O Horan and assigned the vicarage to John Olorchayn (O Lorcan), an Augustinian canon of St. Mary’s.[vii]

Sixteenth century

Within the parish of Lusmagh the ancestral lands of the MacCuolahans lay near its northern border with the MacCoghlan territory, across which raid and counter-raid were common in the late medieval period. There is no evidence to suggest that the family ever constructed or were in a position to construct a tower house or castle for protection on their own lands, the nearest fortified positions within O Maddens country being the castle at Meelick on the western bank of the Shannon and the castle at Cloghan in Lusmagh. From about 1557 the English regained an intermittent control over Meelick and its manor lands, leasing it to those regarded as loyal or of potential service to the Crown.

The castle at Cloghan, however, was a principal fortified residence for an important branch of the O Maddens and served as the seat of power of Owen O Madden, son and younger brother of former chieftains and one of the local leaders of resistance to the Crown in the late sixteenth century. A number of the MacCuolahans were active with many others within Síl Anmchadha in opposing the encroaching power of the Crown in that period. In 1585 the Crown came to an accommodation with the principal men of County Galway whereby the leading men acknowledged their lands as private property, held under English law, in return for the agreed rent and on condition that they provide an agreed number of soldiers to support the administration when required. In so doing the signatories repudiated the Gaelic legal system in favour of that of England and repudiated the old Gaelic system of government, chieftaincies and titles.

That same year of 1585 Donell McWollethan (MacCuolahan) of ‘BallemcWolleghan’ was among those issued a pardon by the Crown. Among others of the wider family issued pardons in the following year were Melaghlin duff (ie. dubh, ‘black’) McCollochan of BallemcCollochan, Donogh McCollochan of the same and Morogh mcCale (ie. ‘son of Cathal’) mcCollochan of Ballemachollocan.[viii]

Nine Years War

In the late sixteenth century war broke out between O Neill, Earl of Tyrone and the Crown. With O Neill initially successful, many of the disenchanted Irish chiefs and lords gathered to the banner of O Neill and that of his ally already in the field, Red Hugh O Donnell and the conflict spread throughout the kingdom of Ireland, beginning what became known as the Nine Years War.

Many of the O Maddens joined O Donnell in the rebellion, with the exception of their chieftain Donal of Longford and his family and supporters. Foremost among the rebels of Síl Anmchadha, which included several senior members of Donal of Longford’s extended family group, was Owen of Lusmagh. A party of dissident O Maddens led principally by Owen of Lusmagh, joined with several of the disaffected Burkes with their Scots mercenaries, were reported about March of 1595 to be ‘lying lurking…in O Maddens country, to enter and spoil MacCoghlan’s country, together with the Kings and Queens counties and so to have joined with Feagh McHugh O Byrne’ a principal Wicklow rebel.[ix] After causing significant damage across O Madden’s territory to those loyal to the Crown, including the destruction of Meelick Castle, the plundering and burning of the town of Clonfert and taking the Protestant Bishop there prisoner, they crossed into MacCoghlans territory.[x] On MacCoghlans information, the Lord Deputy made for the Shannon and on his arrival found many of MacCoghlans towns destroyed. Surprising the rebels, the English, with MacCoghlan’s aid, killed seven or eight score, ‘among whom were the leaders of the Scots and of the best of the rebels the O Maddens.’[xi] ‘The rest got over the Shannon by flight and returned again into Connaght’ with the exception of about forty-five or six who sought the safety of Owen O Madden’s Cloghan Castle, where they were then beseiged.[xii] Several of the MacCoulahans were involved in rebellion, including Molaghlin Duffe McColeghan, described as a ‘Captain of shott’ and his two sons, who were among those killed by the English force at the subsequent taking of Cloghan castle.[xiii]

John McCuolloghan appears to have been one of the most prominent, if not the most prominent, of the name in the late sixteenth century, holding as part of his lands at least two of the three quarters that comprised Ballymacoolaghan. He was among the many rebels killed during the Nine Years War and as such his lands were confiscated. Part of those lands, ‘the quarter called Cograne lying in Ballevicvolloghane’ (ie. Ballymacoolaghan) and one quarter of ‘Carrownakyloge, lying in Ballevervolloghan’ (ie. Ballymacoolaghan) were included as part of vast lands across the country given by the Crown about 1610 to Gerald, Earl of Kildare.[xiv]

Ballymacoolaghan

The three quarters that comprised Ballymacoolaghan consisted at least of the modern townlands of Ballymacoolaghan, Cogran and the townland of Carrowmanagh, the latter lying between the other two and therefore evidently part of the original ‘baile’ of the MacCuolahans. The denomination known as ‘Carrownakyloge’ in the ‘baile’ later became obselete. The three quarters would also appear to have included the modern townland of Ballylier from its description in 1797 as ‘another part of Cogran’ and as the modern townland of Gortarevan lay between the modern townlands of Ballylier, Cogran and Ballymacoolaghan, it is possible it may also have formed part of the three quarters.[xv]

Early Seventeenth century landholders

In the aftermath of the Nine Years War, Owen O Madden’s Lusmagh estate appears to have been confiscated by the Crown. He had been killed in action in late 1598 or early 1599 and four of his sons were still out in rebellion not long thereafter leading a party of fifty foot soldiers.[xvi] Having been slain in rebellion his castle and estate, which formed a large part of Lusmagh, was subject to confiscation and were acquired by John Moore, scion of a Roman Catholic family from Barmeath in County Louth who was active in the Elizabethan administration of Connacht and who had acquired lands about Cloonbigny in County Roscommon in the late sixteenth century.

Brian McCowleghan of Ballymccowleghan in Galway County, gentleman, about 1618 held a half quarter of Ballymccowleghan, while Hugh McCowleghan of Ballymccowleghan held a moiety (ie. half) of the quarter of Cloghrinne (Cogran).[xvii] Melaghlin Duff McCowleghan and Melaghlin oge McMelaghlin McCowleghan of Ballymccowleghan jointly held two thirds of the Culnetrump, while the latter in his own capacity also held lands at Cloonlahan, further west in Sil Anmchadha.[xviii]

John O Donovan gave the same individuals as listed in an inquisition into property taken at Kilconnell in September of 1617 but that inquisition also included one Onora Ny Coolighan, widow, who held a cartron of Carrowanmeanagh (Carrowmanagh).[xix]

While the principal lands of the family lay east of the Shannon, portions of land in the parishes of Abbeygormacan and the adjacent Killoran, further to the west in O Madden’s territory, was held by some members of the family in the early seventeenth century. Donnogh McCoolighan, gentleman, of Adragule (modern townland of Addergoole), in the parish of Abbeygormacan, held one cartron of Adragule in 1618 and Melaghlin oge McMelaghlin McCowleghan, described as ‘of Ballymccowleghan’ also held a portion of the lands of Cloonlahan, that is, one twelfth of the two quarters of Cloonlahan in the parish of Killoran.

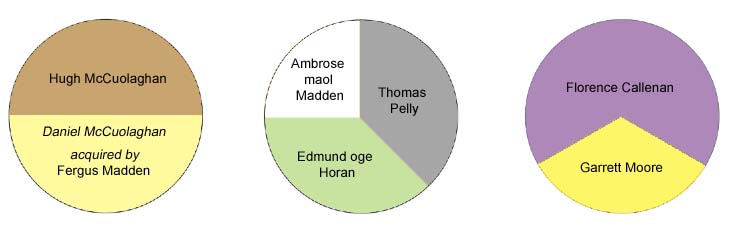

Within about twenty years the greater part of the lands of Ballymacoolaghan had been acquired by others. No MacCuolahan was given in the ‘Books of Survey and Distribution’ as a landed proprietor of property there by at least 1641.[xx] However, Richard Monck, a teacher resident in the town of Banagher who had access to the family documents of the principal branch of the Cuolahans in the mid nineteenth century, gave a detailed account of the ownership of the three quarters that composed Ballymacoolaghan in 1641. In his account, at least one member of the name was still a landed proprietor in that year.

In Monck’s account Hugh McCuolaghan was proprietor of a half quarter of the three quarters of Ballymacoolaghan ‘by descent, which in the year 1641 was in his possession.’[xxi] One Daniel McCuolaghan was also proprietor of a half quarter of Ballymacoolaghan in 1641 but was thereafter mortgaged by him to Fergus Madden, who would appear to have been the significant landowner of that same name who resided at Lismore Castle in the parish of Clonfert on the opposite side of the Shannon. Madden was thereafter the possessor of Daniel McCuolahan’s half quarter ‘by virtue of his mortgage.’ Of the others who possessed the remainder of Ballymacoolaghan in 1641, Florence Callanan of Grange in the parish of Fahy had purchased two thirds of a quarter in fee simple before 1641 while Garrett Moore, the largest landholder in the parish of Lusmagh, possessed one third of a quarter, Ambrose maol Madden of Brackloon Castle in the parish of Clonfert possessed one cartron, Edmund oge Horan was proprietor in fee simple of three half cartrons as was one Thomas Pelly (erroneously given by Monck as ‘Kelly’).[xxii]

Similarly Donagh McCuolaghan’s property in Abbeygormacan had been acquired by one of the O Hannins based about that parish and Melaghlin oge McCuolaghan was no longer owner of his lands at Cloonlahan.[xxiii]

A diagrammatic account of the landownership of the three quarters of Ballymacoolaghan in the parish of Lusmagh circa 1641, after that given by Monck.

Lands mortgaged to Moore of Cloghan Castle

As O Donovan and Richard Monck gave the mid seventeenth century ancestor of the later senior line of the Cuolahans as one Hugh McCuolaghan, whom Monck described as an old man in 1641, it would appear likely that the Hugh to whom they refer was that Hugh who still possessed one half quarter of Ballymacoolaghan in that year.[xxiv] While a senior line of the family would manage to remain seated in Ballymacoolaghan, in that part of the three quarters known as Cogran, they appears to have mortgaged their land to the adjoining landowner Garrett Moore of Cloghan Castle.

The Moores, however, lost possession of their lands as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century and the lands occupied at Cogran by the Cuolahans was said to have been allocated by the Cromwellians to one Alderman Baker. [xxv] Following the turmoil of that period and the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, an Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time. At the Restoration Colonel Garrett Moore, a committed Royalist, was granted possession of his family lands including those of Cogran, by a decree of the Court of Claims ‘and he having either a mortgage on Cogran, or holding it in trust for the Cuolahans, restored it to them.’[xxvi] Barker, some time later, sued the Moores on the basis that they had not been accurate in defining the lands in question and had a large part of Cogran allocated to a Mr. Aston of Dublin, leaving 125 acres remaining as that part of Cogran granted to Colonel Moore.[xxvii]

According to O Donovan, Hugh Cuolahan, son of Hugh son of Bryan son of Donogh Keogh McCuolahan, died in 1667.[xxviii] Monck gave him as the son of that Hugh whom he described as an old man in 1641. This Hugh who died in 1667 is said to have mortgaged half a quarter of Cogran to Garrett Moore, which was later acknowledged in a receipt given by Moore’s son Garrett Moore to Hugh’s grandson Lieutenant Daniel Cuolahan, bearing the words; ‘I have received two papers from Lieutenant Daniel Cuolahan, one relating to half a quarter of Cogran, signed by my father, to leave the said half quarter to Hugh Cuolahan, grandfather to the said Daniel against the plantation intended by Lord Stafford.’[xxix]

In a codicil attached to the last will and testament of Colonel Garrett Moore of Cloghan Castle, King’s County, dated January 1705, Moore stipulated that ‘Daniel Culoghan shall have a lease for 31 years, renewable for 31 years more, for him and children and for no other of the qr. of Cloghrane (recte: Cogran) at 1s. 6d. per acre clear rent above Quit rent and all other charges as I agreed to give him in Croghan last October.’[xxx]

O Donovan and Monck gave one Hugh Cuolahan as the son of that Hugh who died in 1667. This later Hugh Cuolahan would appear to have been the same individual commemorated by a stone memorial erected at the Franciscan friary at Meelick bearing the words; ‘Me fieri fecerunt pro se et posteris suis Hugo Cuollachan, et Izabella Madden, uxor eius Die XX mensis May 1673.’

This Hugh died on 26th February 1686, with the Meelick friars remembering him in their records as a pious and prudent man and a good benefactor to their friary.[xxxi] Hugh’s will identified him as of Cogran.[xxxii] According to John O Donovan, who based his pedigree on information received from one Richard Monck, Esq. of Banagher, this Hugh who died in 1686 was the son of Hugh, son of Hugh, son of Bryan, son of Donogh Keogh MacCuolahan. Donogh, who was living in 1602, was given as the son of Carroll MacCuolahan. Monck, however, in a pedigree table of the family, gave this Hugh, son of that Hugh who died in 1667, as alive on 5th July 1690.[xxxiii]

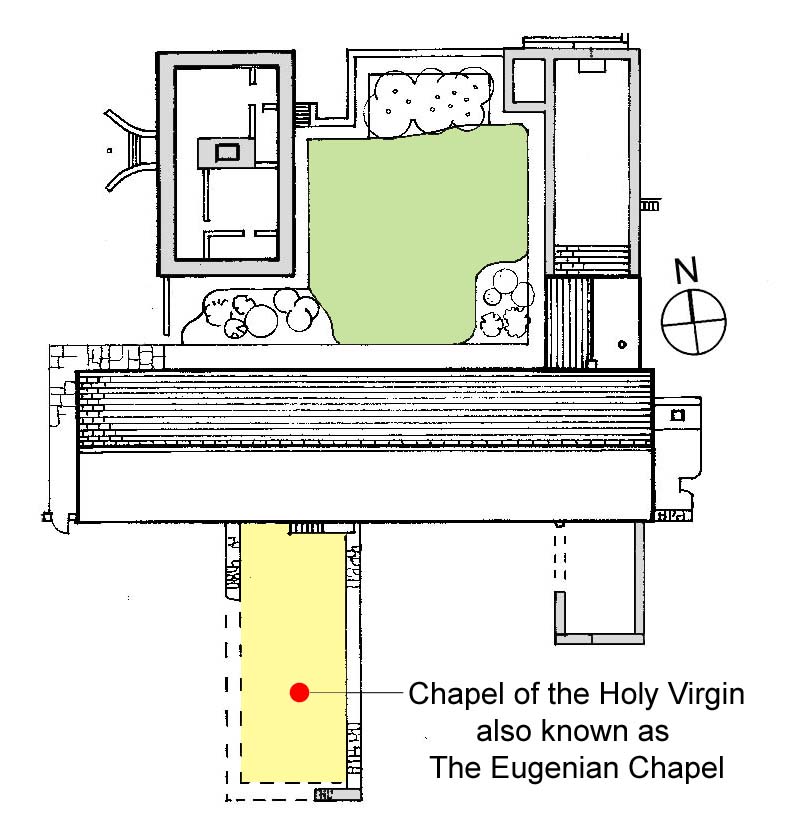

The 1686 obituary of Hugh Cuolahan recorded by the Meelick friars, to whose friary he left a legacy, gave Hugh’s burial place as located in ‘the chapel of the Holy Virgin and that of his ancestors.’[xxxiv] Monck described the commemorative stone as located ‘in the southern transept, on the western side, worked into the wall.’[xxxv] The friary had two transepts on the southern side of its church, a smaller transept or side chapel to the east and a larger to the west, both in an advanced state of ruin in the early nineteenth century. The smaller would appear to have been known as the Lorcan or Larkin chapel, from its donors and the larger as the Madden or Eugenian chapel, the latter name possibly derived from a donor named Owen O Madden. While the Cuolahan stone no longer survives in place, it was the western, Madden, chapel to which Monck referred as the location of the stone and therefore the burial place of the principal line of the Cuolahans. This is confirmed by a description of various commemorative stones and headstones in a transept given by one John D’Alton in an 1847 edition of ‘The Gentleman’s Magazine.’ Having visited the ruined friary, D’Alton referred to the Hugh Cuolahan and Isabella Madden stone as located in the same transept as eighteenth century mural stones commemorating members of a Shea family and a Cananan family, together with a monument to one Valentine Bennett.[xxxvi] All of these survived into the twenty-first century and were located in the larger, Madden, chapel and the Ordnance Survey Letters of 1838 also described the Cuolahan stone as located in the western wall of the same transept as the Cananan stone, thereby confirming that transept as the chapel of the Holy Virgin.

Plan by the author of the restored Roman Catholic church at Meelick, formerly that of Meelick friary, with the location of the ruins of the Chapel of the Holy Virgin shown in yellow, in the western wall of which was once located the Cuolahan memorial stone.

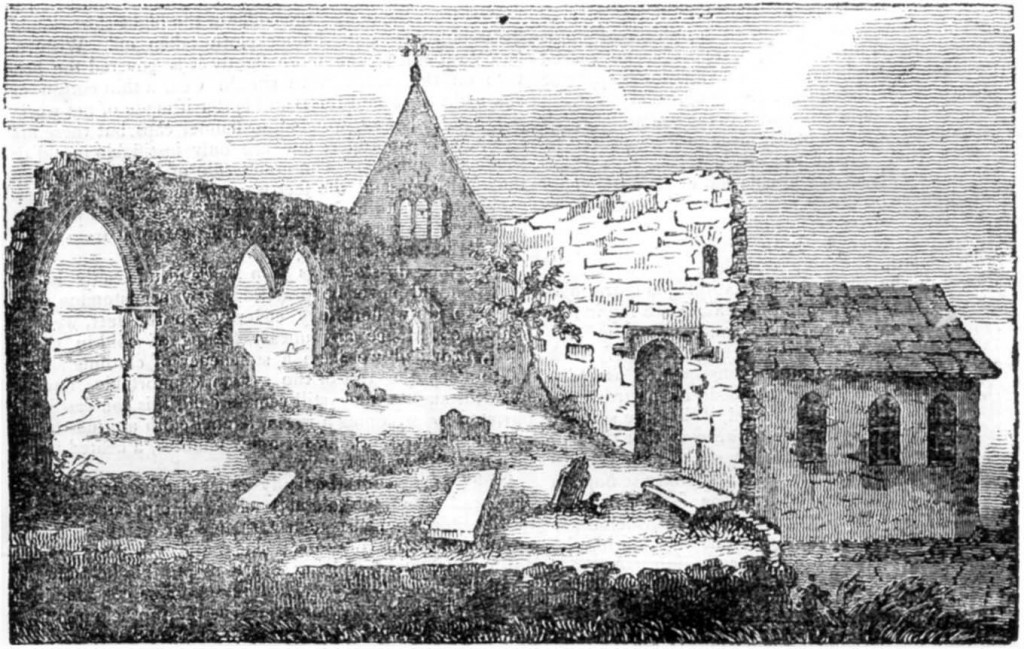

The roofless ruins of the church at Meelick friary in 1833, viewed from the east, its east gable fallen. The barely discernible remains of the Chapel of the Holy Virgin, wherein were buried the Cuolahans of Cogran, were originally accessed through the twin pointed arches on the church’s south wall, their central column also fallen. (The Dublin Penny Journal, Vol. 2, No. 74, 30th November 1833, p. 172).

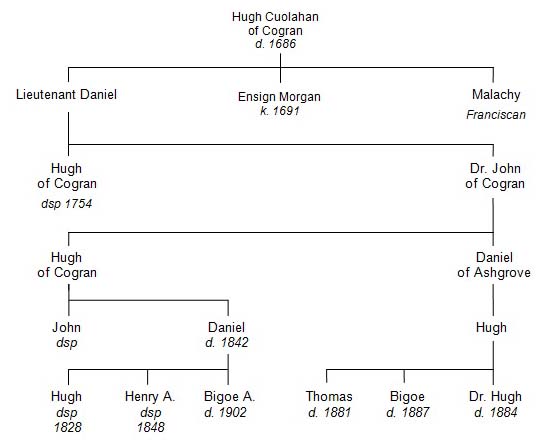

It would appear that Hugh of Cogran, great-great grandson of Donogh Keogh, was the senior-most member of the name at this time, with his sons being the only members of the wider family serving as officers in the Irish army of the Roman Catholic King James II in the late seventeenth century. Hugh and Isabella had at least three sons; Daniel, Morgan and Malachy. Many of the principal Roman Catholic families of county Galway served as officers in the Jacobite army and after the outbreak of the war in Ireland between the supporters of King James II and the Protestant William of Orange, the brothers Daniel and Morgan Cuolahan took up commissions in the Irish Jacobite army. Daniel held the rank of Lieutenant while Morgan that of Ensign, the latter serving in the regiment of Colonel Lord Galway and was killed in battle by chain-shot at Athlone bridge in 1691.[xxxvii] Hugh and Isabella’s third son, Malachy Cuolahan, at the age of twenty years, received the habit of probation in the convent of Meelick, as a cleric. He was professed in Meelick on the 21st January 1683 and changed his name to Francis.[xxxviii]

Lieutenant Daniel Cuolahan married Mary, daughter of Teige Daly ‘of Killemeeny, in the county of Galway’ in 1691. His father-in-law, due to his distressed state of affairs, could only promise in the marriage settlement that he would ‘pay to the said Daniel Cuolahan two hundred pounds sterling, in consideration of a marriage portion, as soone as God Almighty pleases to restore me to my estate.’[xxxix]

Daniel Cuolahan survived the war, which came to a conclusion with the defeat of the Jacobite army and the signing of the Treaty of Limerick in 1691. As an active Jacobite his estate was liable for confiscation but like many he applied to benefit from the articles of Limerick and Galway that formed part of the Treaty. Those who submitted to the new Protestant King and Queen and were eligible to benefit from the articles were to be allowed to keep their estates intact and, if outlawed, pardoned.[xl] Lieutenant Daniel Cuolahan’s claim for admission to benefit under the articles was adjudicated in December 1698.[xli] Like the majority of cases, he was successful and retained his interest in the lands at Cogran.

When the ‘Banishment of Religious Act’ was enacted in 1698, requiring Roman Catholic Bishops and religious to have departed from Ireland before May 1st of that year, many of the remaining religious houses gathered their valuables and dispersed them among several of the surrounding Catholic gentry in the hope of preserving them for future use. The Meelick friars divided their chalices, vestments and books among ten people, one of who was Daniel Cuologhane.[xlii]

He was still living in the early years of the eighteenth century, when, together with one Cornelius Coghlan, another of those entrusted with the valuables of the Meelick friars, he served as a co-signatory on a certificate dated 1704, stating that the island of Murrugh in the Shannon at Meelick (south of the friary) had been the property of the Meelick friars since 1682 and had ‘been credibly informed’ that it had been in their possession ‘for time out of mind.’[xliii]

Conversion to Protestantism

Lieutenant Daniel had two sons, Hugh and Doctor John Cuolahan, both of whom converted to Protestantism. Hugh Cuolahan of Cogran, gentleman, converted in 1740 but died without issue in 1754. His younger brother, Dr. John Cuolahan married one Miss Rock, and Englishwoman and resided in England.[xliv] He returned to Ireland on his brother’s death and embraced Protestantism in December of that same year on coming into possession of the family lands.[xlv] (Another John Cuolahan, with an address of Eyrecourt, converted in 1767). Dr. John Cuolahan suffered financial difficulties, partly attributed to the extravagance of his wife and, on his death in 1761 these difficulties were inherited by his sons Hugh and Daniel.

Richard Monck summarised the financial travails of the family to the antiquary John O Donovan in the mid nineteenth century. ‘It is evident that they are both ancient and respectable, but that they have not ranked as chieftains for many centuries. On the east side of the Shannon, where the family have been located for the last four hundred years at least, they have been in possession of some townlands, never, I think, to an extent of more than eight or nine hundred acres; but what with divisions, mortgages, confiscations, discoveries, etc., they are now left without any real estate. Alderman Barker got from Cromwell all the property that belonged to them, but at the Restoration Colonel Moore was put in possession of it, by a decree of the Court of Claims, and he having either a mortgage on Cogran, or holding it in trust for the Cuolahans, restored it to them. The aforesaid Barker, when matters were somewhat pacified, commenced a suit against the Moores, because they were not sufficiently accurate in defining the lands, and made over about 350 acres to a Mr. Aston of Dublin, measuring off 125 acres, the portion of Cogran granted to Colonel Moore. In fact, were it not for the prudent conformity of Dr. John Cuolahan in 1754, and the marriage of his two sons to the two Misses Armstrong, which gave them a lift, they might now, like the greater number of the descendants of the old Irish chieftains, be reckoned amongst the tillers of the soil.[xlvi]

The two Misses Armstrong

Both of Dr. John Cuolahan’s sons married two sisters, daughters of Archibald Armstrong by his wife Rebecca, only daughter of Captain Michael Armstrong and sister of General Bigoe Armstrong of Winepole Street, London.[xlvii] Hugh, the elder of the two brothers married Jane, the elder of the two Armstrong sisters. Daniel, the younger brother, married Catherine, the younger of the sisters. On the marriage of his two nieces, General Armstrong gave to each a marriage portion of £1,000 and to each of their husbands a half each of Ashgrove, a farm in the Lusmagh townland of Macknahanny or Ashgrove.[xlviii] In addition to the financial support brought by the two Armstrong sisters the Armstrongs appear to have provided later generations of the Coulahans with such Christian names as Archibald and Bigoe, the latter derived indirectly through the Armstrongs from Philip Bigoe, a seventeenth century Huguenot glasshouse owner and landowner who settled at one time at Newtown in Lusmagh.

The senior-most line of the Cuolahans, despite their precarious financial situation, would remain seated at Cogran for several generations while the junior line, descended from Daniel, would be seated at Ashgrove. Hugh of Cogran, by his wife Jane Armstrong, had two sons; John and Daniel, while his brother Daniel of Ashgrove, by his wife Catherine Armstrong, had at least one child, a son named Hugh.

Cogran was described as the house of Hugh Cuolahan in 1775 in a report carried in the contemporary papers on the violent death of a relative, one Henry Pepyat, a shopkeeper in Birr. Pepyat’s son, about nineteen years old, visited his relations at Cogran and his father travelled to Lusmagh to bring home his son on 10th January. Father and son appear to have argued and ‘they were heard to have some very smart words departing the house.’[xlix] The following morning the father’s body was discovered lying in a ditch near Cogran House. His body was said to have on it ‘several marks of violence’ and the subsequent coroner’s inquest delivered a verdict of wilful murder. The principal suspect was Pepyat’s son, given their disagreement of the previous day and his reputedly being ‘always known to be very unruly and disobedient to his parents.’ The son disappeared and, despite a search of the area, could not be immediately found.

Hugh of Cogran’s eldest son John would appear to have been of sufficient age by the early 1790s to attend race meetings. At one such, held at Birr in September of 1793 he rashly insulted the twenty-eight year old John Hubert Moore, a younger brother of Garrett O Moore of Cloghan Castle and who had qualified as a barrister only the year before. As a result of the personal slight, Moore appears to have pursued Cuolahan to the extent that, three years later, John Cuolahan was required to publish an abject public apology. Giving his address as Cogran, Cuolahan had an advertisement inserted in ‘The Dublin Evening Post’ of 8th March 1796 which read; ‘Whereas in the month of September 1793, at the Public Race Course of Birr, I did in the most wanton, provoked and ungentlemanlike manner, insult John H. Moore, Esq. and his profession as a Barrister – Now, being at length brought to sense of the gross impropriety of my conduct on that occasion, I do in this public manner acknowledge my offence against him and his profession in general and do thus publicly solicit his and their forgiveness.’

The Cuolahans were still experiencing financial difficulties in the latter years of the eighteenth century, with John Hone and Anne his wife, alias Todd, taking an action against Hugh Cuolahan and others about 1794 relating to the Cuolahan’s Cogran lands. Following a decree in the High Court of Chancery made in March of 1795 the Cogran estate, comprising of ‘the half quarter of Ballymaccoullehane known by the name of Cogran, two quarters of land known by the name of Cogran, half a quarter and Kinkelly half quarter and Ballyhire alias Ballylier, being another part of Cogran aforesaid, containing in the whole three hundred acres’ were advertised to be set for three years to the highest bidder.[l] The action continued into 1797, with the defendants being described at that stage as ‘Hugh Cuolahan, Jane his wife and others.’ At the end of March of that year, following a decree of the High Court of Chancery of 1796 and a subsequent order of March of 1797, the three hundred acres that comprised the Cuolahan’s Cogran lands was advertised for sale by auction or ‘by public cant to the highest bidder.’ The Cuolahans would manage to retain their presence at Cogran House after this period as tenants on the same lands.

The sale of Cogran and its subsequent purchase by a Mr. Bernard, from whose family the Cuolahans would thereafter leased their lands, was attributed to transactions undertaken by Hugh’s father. Richard Monck, however, attributed the loss of ‘a large portion of Ballymaccoulahan, of which Cogran was but a subdivision,’ in part to Dr. John’s eldest son Hugh. Monck, who had access to the Cuolahan family papers, stated in his own words that Hugh ‘mortgaged a portion of these lands for about £1,000 and when the mortgager was about to foreclose the mortgage, he, by involving himself still more, raised the sum which he sent to Dublin by a relative of his own, a man of the name Daly, but Daly never paid the money (and) Cuolahan was never able to raise his head after. However, he did the best he could, he sold his ancient patrimony or at least what was left of it, securing for his family Cogran, namely to hold it as tenants at a reasonable rent.’ [li]

Cuolahan’s Corps

In the late eighteenth century one of the Cuolahans captained a small force of loyalist volunteers based about Lusmagh, described by a later author as ‘a body of yeomen known as Cuolohan’s Corps’, ‘the most bloodthirsty of all the dogs of war then let loose on this unfortunate country.’[lii] A disparaging account of their activities was given in the description of the taking of a noted locally based rebel named James Meaney, who was involved in the United Irishmen and outlawed in the aftermath of the 1798 rebellion. Having initially taken refuge about Redwood in County Tipperary, he later went into hiding in a cave surrounded by woods not far from Cloghan Castle in Lusmagh, sometime about 1799. On his returning from a friend’s house one night he was forced to hide behind a roadside hedgerow to escape discovery by the passing volunteers. He single-handedly turned the yeomen to flight by presenting himself before them, surprising them and fired a shot at Cuolohan while calling on pretended colleagues to fire also from behind concealed positions. The corps fled but a large body of soldiers was later ordered from Banagher to search the area and Meaney was discovered and shot and his corpse placed on display in chains in the marketplace of Banagher.[liii]

The senior line of Cogran in the early nineteenth century

Of the two sons of Hugh of Cogran, John, the elder, died unmarried and the younger son Daniel inherited Cogran. He married Frances Antisell of Arbour Hill, County Tipperary and was in possession during the land agitation of the early decades of the nineteenth century when the family was targeted by a number of the disaffected local population.[liv] One Dublin newspaper reported that on Christmas Day of 1831 ‘a party of men, well armed with guns and blunderbusses attacked the house of Daniel Coolahan of Cogran in Banagher while the family were at church in Banagher and succeeded in taking therefrom a valuable fowling piece and a case of pistols.’[lv]

Much of the information written by the antiquary John O Donovan in his ‘Tribes and Customs of Hy Many’ was provided by Richard Monck, his friend and former Latin tutor and an anti-clerical schoolmaster with little means and a large family resident for a time at Banagher, near Lusmagh. Monck was familiar with the Coulahan family and with the remaining friars at Meelick, the latter whom he held in mild condescension. He described himself as an intimate acquaintance of Henry Cuolahan of Cogran and the deceased ‘old Hugh’ Cuolahan of Ashgrove and visited Cogran and viewed the family papers, some of which he described as at least two hundred years old and ‘principally leases, deeds and marriage settlements and communications relative to money transactions between the Cuolahans, the McCoghlans, O Moores and O Maddens.’[lvi]

Daniel Cuolahan of Cogran House died on the 16th January 1842.[lvii] Writing to O Donovan from Banagher in early September of that year, Monck informed him that Dan, son of Hugh of Cogran, died about nine months earlier, leaving eight children; two sons and six daughters.[lviii] Hugh, the eldest son of Daniel, had died unmarried and without issue in 1828 during the lifetime of his father and Henry, born in 1819, became head of the family and name on his father’s death.[lix]

Monck described Henry Cuolahan in the Autumn of 1842 as the ‘the eldest surviving son’ of Daniel and as the ‘undoubted head of the family, aged about three or four and twenty and still unmarried’ and in possession of old family documents, which papers were spread out before Monck on a visit to Cogran on at least one occasion in that same September.[lx] He described Henry Cuolahan as possessing ‘so much of the old Irish pride of Clanship as to be willing to assume the ‘Mac’ before his name’ and was of the opinion that if Cuolahan was to see the depth of information and the antiquarian interest shown in his family history and pedigree by O Donovan and others in print, ‘he (Cuolahan) would do so at once.’ [lxi] In preparing his book on the families and customs of the territory of Uí Maine or Hy Many, which would be published in the following year, Monck advised O Donovan to make what mention he pleased of the then head of the family but he assured O Donovan that he knew Henry ‘would feel gratified’ for his so doing. Henry had, Monck believed, ‘no small share of Irish pride about him’ and while his father Dan was often in financial difficulty he ‘always possessed a respected position.’[lxii]

O Donovan’s friend and informant described Henry at that time as holding ‘about 200 acres, which extend to the Shannon, under a lease of lives renewable forever, which is considered a kind of real estate in Ireland, for which he pays about £61 per annum. He has, besides Cogran, some property in the town of Banagher, acquired in the good Protestant times, perhaps from £150 to £200 a year, when a life or two shall have dropped.’[lxiii] ‘They have several tenements in Banagher, in one plot they have four acres facing the street with a row of cabins on it. This they got from the Ladies Louth, who were (at one time) proprietors of Banagher.’[lxiv]

‘At Cogran,’ Monck noted that ‘there is a picture of one of the Cuolahans, perhaps of Dr. John’s father or his brother Hugh. It is well executed, and no doubt a good likeness, at least I am inclined to think so, as I know one of the family, a Mr. Bigoe Coulahan of Ashgrove, of whom it might be considered a likeness at the present day. He was evidently a buck of the day (latter end of Anne) with flowing wig, purple silk velvet coat, gold embroidered waistcoat, &c.’[lxv]

This Bigoe Cuolahan of Ashgrove to whom Monck referred was a distant cousin of Henry’s and shared a Christian name with Henry’s younger brother; Bigoe Armstrong Cuolahan, the latter born about 1824 and aged about eighteen years when Monck was writing to O Donovan of the family.

The junior branch of Ashgrove, Springfield and Ross in the nineteenth century

Monck informed O Donovan in the early 1840s that there was at that time ‘two (leading) families of Macoulaghans’ who spelled their name Cuolahan, both of whom resided in the parish of Lusmagh. While he described the head of the family as Henry Cuolahan, Esq. of Cogran House, the other branch he described as ‘of Ashgrove.’[lxvi]

Monck made reference to one Dr. John Colohan, a contemporary whom he said lived at either Ballinasloe or Galway, but he knew nothing of his pedigree and doubted if his family could connect their line to that of Cogran or Ashgrove. ‘There are,’ he said, ‘two or three more families of the Cuolahans about the place’ but none of whom could make a direct familial connection with the two principal lines.[lxvii]

Select pedigree of the Cuolahans of Cogran and Ashgrove with female members omitted.

The junior line of Ashgrove, cousins of the Cogran line, descended from the marriage in the eighteenth century of Daniel, younger son of Dr. John Cuolahan and Catherine Armstrong.[lxviii] This branch Monck stated consisted of three brothers; Tom, Bigoe and Hugh and three sisters.[lxix] Tom, he described, as ‘a worthy young man,’ the head of the Ashgrove branch and ‘the son of Hugh son of Dan son of Dr. John.’[lxx]

Both Tom and Bigoe married two sisters. Thomas Cuolahan of Ashgrove married Alice, the eldest daughter of Captain Cuolahan of Milfield, County Donegal and of Her Majesty’s 98th Regiment of Foot in 1839.[lxxi] The bride’s father, Daniel Cuolahan, was deceased by the time of her marriage, having died in 1827.[lxxii] The couple appear to have had a number of children, with the ‘Dublin Morning Register’ of the 6th January 1841 reporting the birth of a son at Ashgrove to Thomas and his wife. The identity of this son born in 1841 is uncertain. The couple had one son named Hugh, who later immigrated to the United States and who was also known to some as John S. Culan or Culen or John H. Coolen.[lxxiii] Thomas and Alice Cuolahan of Ashgrove had at least one other son, born about 1847, named Archibald Thomas Cuolahan.[lxxiv]

Monck stated in 1842 that Ashgrove ‘was out of lease some three or four years ago and Tom now rents it or about forty acres of it from O Moore of Cloghan castle.’ ‘This’ Monck stated ‘is all he has.’[lxxv]

The Cloghan Castle estate of Garrett O Moore, in their family’s possession for approximately two hundred and fifty years, was put up for auction in 1852. The rental records from the proposed sale gave Thomas Cuolahan as holding a lease, dated 10 July 1837, relating to lands in the townland of ‘Macknahanny or Ashgrove.’ The lands were leased by Garrett O Moore to Thomas Cuolahan at a yearly rent of £32 ‘for lives of said Thomas Coulaghan, Bigoe Coulaghan, brother of the said Thomas and Butler Dunboyne Moore, son of Hubert Butler Moore of Shannonview, County of Galway or 31 years, whichever shall be longest.’ Also in the same townland Thomas Cuolahan leased other lands from the O Moore estate, but as a tenant on a year to year basis, determinable on the 1st day of November of each year, at an annual rent of £16. By the middle of the 1850s Cuolahan was leasing his Ashgrove lands from the Armstrong estate. About 1855 he was tenant of John P. Armstrong, who possessed all the lands of that townland and from whom Cuolahan rented his house, offices and land of about 156 acres, including also a herd’s house and garden.

Thomas Cuolahan of Ashgrove may have died in 1881 as one of that name died in September of that year, with his death recorded in the Parsonstown District, aged seventy-six years.[lxxvi]

Bigoe Cuolahan, the second son of Hugh of Ashgrove appears have been that Bigoe Cuolahan who resided by the mid 1850s at Ross House, Parsonstown (Birr). Bigoe Cuolahan ‘of Ross House, County Tipperary’ married on 30th June 1855 Jane Haslett Cuolahan, second daughter of the late Captain Cuolahan of Milfield, County Donegal ‘and formerly of Her Majesty’s 98th Regiment of Foot.’[lxxvii] The wedding ceremony was held at Palace Church in County Tipperary. Although the couple remained together until his death, Bigoe Cuolahan had by one Emily Erlessy a son Charles Cuolahan, born on the last day of July 1858.[lxxviii] When Bigoe Cuolahan of Ross House died on or about 3rd September 1887 at his home, probate was granted to Charles A. Cuolahan of Ross House, Farmer, the sole executor.[lxxix] In addition to Charles and it would appear another son named John Theodore, Bigoe Cuolahan had a daughter, born about 1862, named Emily Jane, who would later marry one Matthew Ferguson from Limavady, county Derry.[lxxx]

Charles, the son of Bigoe Cuolahan and Emily Elessy, married Matilda and appears to have immigrated to the United States of America. The family do not appear to have continued at Ross House beyond the death of Bigoe. When John Theodore Cuolahan died on 22nd December 1895 he was described as ‘formerly of Ross, County Tipperary (the house lying close to the King’s County border with County Tipperary) and late of Birr, King’s County, Farmer.’[lxxxi] He died at the relatively young age of thirty-four years.[lxxxii] John Theodore appears to have been a younger son of Bigoe Cuolahan and does not appear to have left issue. His will was proved by Archibald Thomas Cuolahan of Springfield, Birr, Farmer, the sole executor.[lxxxiii]

Bigoe Cuolahan’s widow Jane Haslett left Ireland some time after her husband’s death and was resident at 9 Church Avenue, Weaste, near Manchester, at her death on 26th September 1895.[lxxxiv] Probate was taken out in February 1897 by Emily Jane Ferguson, wife of one Mathew Ferguson.

It would appear Bigoe Cuolahan and Jane Haslett may have had another son in Thomas Cuolahan, who was party to a law suit taken by Emily Jane Fergusan and her brother Charles A. Cuolahan against their cousin Archibald T. Cuolahan.

A legal dispute arose in the late nineteenth century between the Fergusons and those who may have been the other descendants of Bigoe Coulahan on one side and Archibald T. Cuolahan on the other. Archibald Thomas Cuolahan married Margaret Gertrude Talbot, sixth daughter of John Talbot of Cloughprior House, Borrisokane, County Tipperary in 1895 in Dublin.[lxxxv] At his marriage Archibald was already resident at Springfield, a house and farm in the townland of Clonoghil Upper on the eastern outskirts of the town of Parsonstown or Birr. Both described themselves as Presbyterians and had one child, a son, born about 1897, named Hubert B. A. Cuolahan.[lxxxvi]

Emily Jane Ferguson of Liverpool Street, Sealy, Manchester and others brought an action against Archibald Cuolahan of Springfield, Birr, King’s County ‘for a declaration that under the will of Maria Smith, late of Birr, Thomas Cuolahan and Bigoe Cuolahan became entitled on her death to the lands of Springfield, Crinkle and Birr in equal moieties and that the plaintiff, Emily Ferguson, (was) now entitled to one third part of the lands through Bigoe Cuolahan and an annuity of £20 per annum charged on the lands became merged in the inheritance.’[lxxxvii] The Thomas and Bigoe in question would appear to have been the two brothers, sons of Hugh of Ashgrove.

Archibald T. Cuolahan appears to have farmed the Spingfield lands and the action appears to have been brought against him principally by his cousins, the offspring of his uncle Bigoe Cuolahan as Emily Jane Ferguson was joined in the action against Archibald Cuolahan by both Charles A. Cuolahan and Thomas Cuolahan. As Charles A. Cuolahan was her elder brother, it would suggest that the Thomas who was also joined as a party with her in the action was another brother.

Solicitors acting for the plaintiffs, including Charles A. and Thomas Cuolahan, sought information in 1900 on one member of the family, news of whom had not been heard since 1877. Advertisements were placed in American newspapers requesting information on whether ‘Hugh Cuolahan (otherwise John S. Culan or Culen otherwise John H. Coolen) son of Thomas Cuolahan and formerly of Springfield, Birr, King’s County, Ireland, who went to the United States of America over twenty years ago and when last heard of in 1877 resided at Walnut Bureau County in the State of Illinois.’[lxxxviii] The plaintiffs desired to know if he was still living, whether he ever married and if so, did he have offspring and the identity of any legal personal representative that he may have had.

The legal case came before the Court and a final decree was made in 1902. The plaintiffs were represented on the day by their barrister, instructed by their solicitors but the defendant, Archibald T. Cuolahan, did not appear. ‘The Chief Clerk found the defendant to be indebted to the estate in £69. He fixed a profit rent of £76 on the lands held by the defendant and found him indebted to the estate in £796 on foot of rent.’[lxxxix]

The connection with members of a Smith family appears to have dated from the late eighteenth century as Archibald claimed that he was a great grand-nephew of one Robert Smith, a porter merchant of Smock Alley, Dublin. Smith was adjudicated a bankrupt in 1797 and died in 1803.[xc] A dividend was paid to creditors but there was insufficient funds to meet the financial demands of his creditors. It was discovered by about the turn of the twentieth century that ‘a small sum invested at the time by the Court as being too trifling for distribution (had), by the accumulation of compound interest, in a hundred odd years, developed into four figures, enough to pay off all the debts and leave a good sum for law costs.’[xci] The Court advertised for representatives of the original creditors to now present their claims. None of the Cuolahans were creditors to whom monies were owed when Smith was declared bankrupt but an administrator was required to distribute the remaining assets and Archibald Thomas Cuolahan applied in 1908 in the Probate Court to take administration de bonis non to the goods of the same Robert Smith, claiming a familial relationship as his great grand-nephew.[xcii]

Emily Jane ‘and others’ appears to have been successful in their legal case as the lands in Springfield otherwise Clonoghil, Drumbane otherwise High Street in Birr and at Crinkle otherwise Clonlagagh, all in King’s County were sold through the Irish Land Commission ‘in the matter of the estate of Emily Ferguson and others’. Any of those claiming to be Incumbrancers affecting the proceeds of the sale of the same lands were invited to present their claims to the Master of the Rolls at the Four Courts, Dublin on or before 29th June 1916.[xciii]

Archibald Thomas Cuolahan died in 1924, aged about seventy-seven or seventy nine years.[xciv] His widow Margaret Gertrude ‘of Springfield, Clonoghil, County Offaly’ died on the 3rd October 1938 in Northern Ireland and probate was later granted at Belfast to their son Hubert B. Cuolahan, his occupation given at that time as farmer.

Charles and Matilda Cuolahan, after leaving Ireland, appear to have settled about the Pennsylvania area and he found employment as a gardener. He died at the age of seventy-four years at Philo Hospital for Mental Diseases on 12th February 1933, three days after being admitted.[xcv] His death certificate was completed on information provided by his widow.

Dr. H. Cuolahan of Bermondsey, London

Hugh, the youngest of the three sons of Hugh of Ashgrove, was born about 1819 and pursued a medical career in England. In 1851 he was unmarried and living at 96 St. Georges Street in the parish of Bermondsey, Southwark in London, where he described himself as a thirty-two year old ‘practitioner.’ In 1858 he was described as a surgeon resident at Bermondsey at his marriage at the parish church of Lewisham, Kent that year to Maria Caroline, eldest daughter of John Matthew, Esq. of Blackheath.[xcvi] From about the time of his marriage until his death he lived at No. 9 Grange Road, Bermondsey, London S.E.[xcvii]

Hugh and Maria Caroline Cuolahan had at least five children, three sons and two daughters; John Herbert, born about 1859, Archibald, born in late 1860, Maria, born in 1863, Frederick, born in the following year and Lillian A. Cuolahan, born about 1869.[xcviii] For much of the children’s younger years the family had three servants in the family home.

Hugh Cuolahan M.D. died ‘very suddenly’ at his residence on Grange Road on 20th August 1884, leaving personal effects valued at £4,339 12s 4d. His widow Maria Caroline was the sole executrix of his will, proved the following month.[xcix] She appears to have moved following her husband’s death and was resident at 87 St. Helen’s Gardens, North Kensington in Middlesex at her death ten years later on 14th September 1894. Probate was taken out on her will two months after her death by John Herbert Cuolahan, Surgeon and Henry George Betts, Estate Agent.[c]

In 1911 John Herbert Cuolahan, a surgeon in private practice, was living at Grange Road, Bermondsey with his wife Emily Maude. When the national census was taken in that year their twelve year old niece Pussie Maud Lillian Clarke was staying with them. While John Herbert’s father had lived at no. 9 Grange Road, John Herbert was resident at 40A Grange Road at the time of his death, which occurred on 11th February 1927.[ci] He was survived by his widow Emily Maude.

Both of John Herbert’s two brothers, Archibald and Frederick immigrated to the United States of America, the former in 1887.[cii] Archibald went to study at Rush Medical College, Chicago in the year of his arrival and became a physician. He married Hattie Luella Shockley from Lamont, Wisconsin about 1892 and had three children; David Hugh, born in Fayette, Lafeyette, Wisconsin in 1894, Paul Bigoe, born in Merrill Lincoln, Wisconsin in 1896 and Mary, also born in Merrill, Lincoln, Wisconsin in 1902.[ciii] In 1910 the family were living in Dewitt, Clinton County in Michigan and it was there he resided at the time of his death two years later as a result of complications during surgery.[civ] He was buried in Dewitt City Cemetery.[cv]

Frederick Hugh, the youngest son of Dr. Hugh and Maria Caroline Cuolahan, immigrated to the United State of America in 1880 or 1884 and never married.[cvi] In 1910 he was forty-seven years old and working as a drugstore salesman and renting a room in the house of Hugh F. McDonald, a physician originally from England and his wife Hannah in Hollandale, Iowa, Wisconsin.[cvii] He was still boarding with the McDonalds ten years later but working as a labourer.[cviii] In 1930 he appears to have had no occupation and living in Hollandale but along with two other boarders in the house of a German immigrant and liveryman named John Mendt and Mendt’s wife and nephew.[cix] Frederick Hugh Cuolahan was still living in Hollandale in 1939 when, at the age of seventy-five years, he became a citizen of the United States of America.[cx]

Bigoe Armstrong Cuolahan, the last of Cogran

Henry Antisell Cuolahan of Cogran House, the senior-most representative of the name, died on the 9th March 1848.[cxi] Cogran thereafter came to be inherited by Bigoe A. Cuolahan at the age of about twenty-four years. In the mid 1850s Cogran House, offices, and lands of about 91 acres, together with a herd’s house and lands of 16 acres and a caretaker’s house and land of 3 acres, all in the townland of Cogran, was rented by Bigoe Coulahan from Captain Thomas Bernard, who possessed all the lands of that townland. In addition Bigoe also rented 45 acres at Ballylier in Lusmagh and about 11 acres at Banagher from the same Captain Bernard and simultaneously rented two houses and lands of about 12 acres in Macknahanny or Ashgrove from John P. Armstrong.

Bigoe A. Cuolahan resided at Cogran alongside his sisters prior to their marriages. Eliza, daughter of the deceased Daniel Cuolahan of Cogran House married Cortland Ross Manifold Esq. of Island Castle in King’s County at Eyrecourt about June of 1854.[cxii] She gave birth to a son at Cogran House, described as her residence, in November four years later.[cxiii] About three months later, on 10th February 1859 her sister Sarah Helena Cuolahan married Henry Wheeler, Esq., of Bandon, Co. Cork at Eyrecourt.[cxiv] Two of their sisters appear to have married two men named Douglas and came to reside in the United States of America. Mary Jane married James Douglas in New York in late 1856 or early 1857 while Grace Douglas, the youngest of all the sisters died of cholera in New York in August 1866.[cxv]

Thomas Lalor Cooke, writing in his 1875 history of Parsonstown stated that ‘since Mr. Henry Cuolahan’s death his brother Mr. Bigoe Armstrong Cuolahan of Cogran, should therefore be the chief representative of this ancient family.’[cxvi] Given Cooke’s understanding that Bigoe A. Cuolahan was the head of the family and his occupancy of Cogran after Henry’s death, it would appear that Henry died without male issue.

In December of 1865 Bigoe A. Cuolahan, Esq. of Cogran House married Loveday, fifth daughter of the late Godfrey Knight, Esq. of Chequer Hill, County Galway at Street in County Westmeath.[cxvii] Loveday Cuolahan died in March of 1878 and Bigoe Armstrong Cuolahan married his second wife, Rebecca, in the following year.[cxviii]

The financial difficulties experienced by the family at Cogran continued into the late nineteenth century to the extent that Bigoe A. Cuolahan was in arrears to his landlord by the late 1880s. In September of 1888 the Freemans Journal, dated the 13th of that month, reported that ‘Mr. Bigo Cuologhan of Cogran House, Lusmagh, was today evicted for arrears of rent from his farm, which was occupied by his family for several centuries. The landlord is Captain W. S. Bernard J.P., Castlebernard, Kinnity. Mr. Cuolaghan is believed to be the first Protestant evicted in King’s County in recent years.’[cxix] Cuolahan managed to maintain his presence at Cogran despite the eviction process as he and his wife were still resident there thirteen years later.

At the Census of Ireland undertaken in 1901 Bigoe A. Cuolahan was ‘head of the house’ at Cogran, a member of the Church of Ireland and then aged seventy-seven years, who described himself as a retired farmer. His wife Rebecca described herself as a Weslyan Methodist, born in Queen’s County and then aged sixty-six. One servant was in the house at the time of the census.

Bigoe Armstrong Cuolahan died less than a year later, at the age of seventy-eight years, in 1902.[cxx] He does not appear to have had any issue by his wife Rebecca as she was still living at Cogran in 1911 when, in the census records of that year, she described herself as having been married for twenty-two years and having no children living.

The overgrown ruins of Cogran in the early twenty-first century, viewed from the east. Local tradition relates that the condition of the house was such in 1902 that, on the death of Bigoe Armstrong Cuolahan, it was considered prudent to carry his body downstairs and place his corpse in the coffin there, the staircase being in an advanced state of decay and it was feared that it may not have borne the combined weight of both coffin and corpse.[cxxi]

With the death of Bigoe A. Cuolahan without issue the line of Cogran that descended from Hugh Cuolahan and his wife Jane Armstrong became extinct and the senior-most male descended from Hugh’s brother Daniel and his wife Catherine Armstrong of Ashgrove would have become the senior-most representative of the name. In 1902 this individual would appear to have been the eldest son of Thomas and Alice Cuolahan of Ashgrove.

Of the sons of Thomas and Alice of Ashgrove, it is unclear what became of Hugh (also known as John), who settled in the United States of America, details of whom was unknown to others of his family in 1900. Their grandson Hubert Bygo Armstrong Thomas Cuolahan, son of Archibald Thomas of Springfield, was resident at 574 Stratford Road, Old Trafford, Stretford in Manchester at the time of his death in 1959.[cxxii] He died at Withington Hospital in Manchester on the 18th December of that year and probate was granted to his widow Mary Cuolahan.

For the arms of the principal branch of the name refer to ‘Cuolahan’ under ‘Heraldry.’

[i] Knox, H.T., The Early Tribes of Connaught: part 1, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth series, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1900, p. 349; Mannion, J., The Senchineoil and the Sogain: Differentiating between the Pre-Celtic and early Celtic Tribes of Central East Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 58, 2006, pp. 166, 168; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Leabhar na g-ceart or The Book of Rights, Dublin, M.H. Gill, for the Celtic Society, 1847, p. 106.

[ii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 39-41.

[iii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 24-59.

[iv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 41.

[v] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 39-41.

[vi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 40- 41.

[vii] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 8: 1427-1447, London, (1909), Lateran Regesta 330: 1435-6, p. 542.

[viii] Fiants Eliz. I

[ix] Cal. State Papers, Eliz I 1592-1596, 1890, pp. 489-491

[x] Calendar State papers 1595-6, vol. clxxxvi. A contemporary English report, from February of that year, attributed much of the damage done principally to the sons of Redmond na scuab Burke of Clontuskert, describing their spoilation of Clontuskert, ‘Ballanavan’ and the Castle and town of Meelecke in O Maddens Country.

[xi] Cal. State Papers, Eliz I 1592-1596, 1890, pp. 499-500. Mr John Lye to Sir Geoff Fenton. ‘from the defaced castle of Cloghran in Losmagh’ 1595-6 March 13.

[xii] Cal. State papers, Eliz I 1592-1596, 1890, pp. 489-91

[xiii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 150.

[xiv] Calendar Patent Rolls, 7 Jas. I, pp. 161-2, LXVII.

[xv] Saunder’s News-Letter, 13th March 1795.

[xvi] Cal. Carew Mss. 3, 1589-1600, p. 300 ‘A general computation of the Irish forces in rebellion when the Earl of Essex arrived in Ireland.’

[xvii] John O Donovan gives this Clogrinne as listed in an inquisition of 1617 as Cogran.

[xviii] Cal. Pat. Rolls, 16 James I., p. 415. The remaining one third of Culnetrump was held by John More of Cloghan castle.

[xix] In the 1617 Inquisition O Donovan gives one Gael mcFariagh as seized of fee of Coreclogha.’ This ‘Gael mcFariagh’ mentioned is more properly ‘Cael’ or Cathal McFeriagh O Madden of Coreclogha, one of a sept of the Maddens seated about Lismore across the Shannon in the parish of Clonfert and not of this family.

[xx] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 199-201.

[xxi] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[xxii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842; The Books of Survey and Distribution describe Ambrose maol O Maddin as the son of Rory, Florence Callanan as the son of Richard Callanan and Edmund O Horan as the son of Connor son of Dermot O Horan.

[xxiii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 186-7.

[xxiv] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[xxv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[xxvi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[xxvii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[xxviii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6; RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[xxix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[xxx] Analecta Hibernica, No. 29, I.M.C., 1980, The Lynch Blosse Papers, p. 151.

[xxxi] N.L.I., Dublin, MS. 5203, Copy of records of the Franciscan Convent of Meelick, Co. Galway, made by Fr. James Hynes in 1858. ‘Obiit in Domino, Dnus. Hugo Cuolaghane, vir pius er prudens et hujus conventus insignis benefactor R.I.P.’

[xxxii] O Cearbhaill, D, The Colahans, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 54.

[xxxiii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[xxxiv] Fennessy, I., OFM, The Meelick Obituary and Chronicle (1623-1873), Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 60, p. 342.

[xxxv] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (viii). Letter dated 17th September 1842.

[xxxvi] ‘In a transept are monuments to Valentine Bennett obit 1768; a mural slab erected by Hugh Callanan (recte: Cuolahan) and Isabella Madden his wife in 1673; a monument to Francis Madden who died in 1743; mural slabs to Sheas since 1774; old monuments to Horans of Muckinagh; mural slab to William Cananan obit 1721 and his descendants to 1817 and numerous modern monuments to the Maddens, all the soil which the descendants of a powerful sept are now permitted to possess.’

The O.S. Letters of 1838 give more detail on the Cananan and Coulahan slabs; ‘in the east wall of the branch building which is attached to the south side wall is inserted a stone bearing an inscription which mentions several persons of the name Cananan who died respectively in 1721, 43, 67 and 1770 and 1817 and were interred here. In the western wall of the same building is a stone inscribed; ‘Me fiery fecurant pro se et posteris suis Hugo Cuollachan et Izabella Madden, uxor eius Die XX mensis May 1673.’

[xxxvii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6; RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[xxxviii] Giblin, C., OFM, Papers relating to Meelick Friary 1644-1731, Collectanea Hibernica, No. 16, B. Millett OFM (general editor), Naas, Leinster Leader ltd., 1973, pp. 50-88

[xxxix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[xl] Simms, J.G., Irish Jacobites, Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, 1960, pp. 14-5.

[xli] Simms, J.G., Irish Jacobites, Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, 1960, p. 107.

[xlii] I. Par. Returns, Y.6, B.73, unnumbered.

[xliii] Giblin, C., OFM, Papers relating to Meelick Friary 1644-1731, Collectanea Hibernica, No. 16, B. Millett OFM (general editor), Naas, Leinster Leader ltd., 1973, pp. 50-88

[xliv] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[xlv] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[xlvi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[xlvii] Burke, J (ed.), A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. IV, London, Henry Colburn Publisher, 1838, p. 347; RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[xlviii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii. Letter dated 5th September 1842.

[xlix] Hibernian Journal or Chronicle of Liberty, 16th January 1775.

[l] Saunder’s News-Letter, 13th March 1795.

[li] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lii] O Hanlon, J., Irish folk-lore: traditions and superstitions of the country, with humerous tales, by ‘Lageniensis’, Glasgow, Cameron and Ferguson, 1870, p.222-223.

[liii] O Hanlon, J., Irish folk-lore: traditions and superstitions of the country, with humerous tales, by ‘Lageniensis’, Glasgow, Cameron and Ferguson, 1870, p.222-223. Meaney was said to have been born about 1770 at ‘Tenescragh, in the county of Galway’, (apparently Tiranascragh), the son of a respectable farmer. Meaney settled later about Redwood in County Tipperary. While Meaney lay concealed in a cave near Cloghan castle he was reputed to have been betrayed by a girl who brought him provisions and he was shot at his hiding place.

[liv] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842; Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent, 31st Dec. 1831.

[lv] Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent, 31st Dec. 1831.

[lvi] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lvii] Freeman’s Journal, 20th January 1842.

[lviii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lix] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842. Monck states in this latter that Henry Cuolahan was born in 1819.

[lx] NLI, Dublin, Ms. 24,039/JOD/239, ‘Graves Collection/John O’Donovan Series/Number 239.’ Richard Monck, Banagher and Birr, to John O Donovan

[lxi] NLI, Dublin, Ms. 24,039/JOD/239, ‘Graves Collection/John O’Donovan Series/Number 239.’ Richard Monck, Banagher and Birr, to John O Donovan. Monck visited Meelick and ‘Mr. Fannin, the only inmate of the abbey’ with a view to inspecting the friary register and funereal monuments to gather additional genealogical information.

[lxii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 (ix). Letter dated 12th September 1842.

[lxiii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[lxiv] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lxv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 183-6.

[lxvi] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lxvii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii. Letter dated 5th September 1842.

[lxviii] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lxix] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lxx] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lxxi] Dublin Weekly Register, 24th August 1839.

[lxxii] Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858, p. 184.

[lxxiii] The Chicago Tribune, 6th March 1900, p. 10. Legal Notices.

[lxxiv] Census records of 1901 and 1911 suggest that Archibald T. Cuolahan was born about 1845 but at his death his age was given as seventy-seven years, suggesting a birth date of about 1847 and in 1851 he was given as the four year old son of Thomas and Alice Cuolahan of Ashgrove.

[lxxv] RIA Library, Dublin, Graves Collection, John O Donovan Correspondence, 24-0-39/JOD/ 239 vii, viii, ix.

[lxxvi] Civil Registration, Deaths Index 1864-1958, Vol. 3, p. 347.

[lxxvii] Freeman’s Journal, 6th July 1855; The Cork Daily Reporter, Monday 9th July 1855.

[lxxviii] Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Dept. Of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate of Charles Cuolahan, Philo Hospital for Mental Diseases, U.S.A., District No. 450, File No. 11514, Reg. No. 3134, date of death February 12th 1933.

[lxxix] National Probate Calendar; England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations 1858-1966), year 1887.

[lxxx] Emily Jane Ferguson, wife of Matthew Ferguson was living at Salford in Lancashire in 1911 and gave her place of birth as Ross, County Tipperary.

[lxxxi] National Probate Calendar; England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations 1858-1966), year 1896, p. 86.

[lxxxii] Civil Registration, Deaths Index 1864-1958, Vol. 3, p. 382.

[lxxxiii] National Probate Calendar; England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations 1858-1966), year 1896, p. 86.

[lxxxiv] National Probate Calendar; England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations 1858-1966), year 1897.

[lxxxv] Civil Registration, Marriages Index 1845-1958.

[lxxxvi] Census of Ireland, 1901, 1911.

[lxxxvii] Northants Evening Telegraph, 14th May 1902. Chancery Division. Ferguson v. Cuolahan.

[lxxxviii] The Chicago Tribune, 6th March 1900, p. 10. Legal Notices.

[lxxxix] Northants Evening Telegraph, 14th May 1902. Chancery Division. Ferguson v. Cuolahan.

[xc] Freeman’s Journal, Wed. 10th June 1908.

[xci] Freeman’s Journal, Wed. 10th June 1908.

[xcii] Freeman’s Journal, Wed. 10th June 1908; Liverpool Mercury, 7th July 1899.

[xciii] Nenagh Guardian, Saturday,15th July 1916, p. 4.

[xciv] Civil Registrations, Deaths Index, 1864-1958, Vol. 3, p. 203. His age at death was given as seventy-seven years but earlier census records of 1901 and 1911 suggest that he was born about 1845.

[xcv] Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Dept. Of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate of Charles Cuolahan, Philo Hospital for Mental Diseases, U.S.A., District No. 450, File No. 11514, Reg. No. 3134, date of death February 12th 1933.

[xcvi] Leinster Express, Sat. March 13th 1858, p. 4. He was described as Hugh Cuolahan, Esq. of Bermondsey, Surgeon, son of the late Hugh Cuolahan Esq. of Ashgrove, King’s County.

[xcvii] The Medical Register 1879, p. 192.

[xcviii] Census of England, 1861, 1971, Parish of Bermondsey, London.

[xcix] National Probate Calendar, England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1855-1966, year 1884, p. 466, year 1894, p. 179.

[c] National Probate Calendar, England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1855-1966, year 1884, p. 466, year 1894, p. 179.

[ci] National Probate Calendar, England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1855-1966, year 1927.

[cii] U.S. Federal Census 1910.

[ciii] 1910 Federal Census Records, Dewitt, Clinton, Michigan; Michigan Deaths and Burials Index, 1867-1995. Archibald’s father was given as ‘Hough Cuolahan’ and mother as ‘Maria Maher’ (recte; Matthew).

[civ] Directory of deceased American physicians 1804-1929; National Probate Calendar, England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1855-1966, year 1918, p. 640.

[cv] A carved symbol upon his headstone would suggest that he was a freemason.

[cvi] U.S. Federal Census, 1910 gave the year of immigration as 1884, while the U.S. Federal Census records of 1930 give the year as 1880. Another source gave the date as 1892.

[cvii] U.S. Federal Census 1910.

[cviii] U.S. Federal Census 1920.

[cix] U.S. Federal Census 1930.

[cx] U.S. Naturalization Records Index 1791-1992.

[cxi] Freeman’s Journal Fri. March 24th 1848, p. 4. Deaths. On the 9th Inst. Henry Antisell, eldest son of the late Daniel Cuolahan, Esq. of Cogran House in the King’s County.

[cxii] Leinster Express, Sat. July 1st 1854.

[cxiii] Leinster Express, Sat. Dec. 4th 1858, p. 4.

[cxiv] Urban, S., The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review, London, J. Henry & J. Parker, 1859, Vol. VI, p. 421.

[cxv] Freeman’s Journal, 12th Jan. 1857; Belfast News-Letter, 13th Oct. 1866.

[cxvi] Cooke, T. H., The Early History of the Town of Birr or Parsonstown, Robertson & Co., Dublin, 1875, p. 347.

[cxvii] Freeman’s Journal, Fri. Dec. 22 1865, p. 3.

[cxviii] Civil Registrations, Deaths Index, 1864-1958, Vol. 3, p. 521; Civil Registrations, Marriages Index, 1845-1958, Vol. 3, p. 257. Loveday Knight was born circa 1839.

[cxix] Freeman’s Journal, Thurs. Sept. 13 1888, p. 6.

[cxx] Civil Registrations, Deaths Index, 1864-1958, Vol. 3, p. 287.

[cxxi] Information provided by Mr. G. Searson, Cogran, proprietor of the lands upon which the ruins of Cogran stood in 2015. The Christian name Bigoe was pronounced locally as ‘Bye-go.’

[cxxii] National Probate Calendar, England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1855-1966, year 1960, p. 732.