© Donal G. Burke 2014

The ruins of Donanaghta church in the diocese of Clonfert are situated in the modern townland of Eyrecourt Demesne, within the barony of Longford in the east of County Galway. As such it lay in the late medieval period within what was for the most part the territory of Síl Amnchadha, ruled by the O Madden chieftain.

Situated on the south-western slope of Redmount Hill, near and to the north of the modern village of Eyrecourt, it derives its name in the Irish language, ‘Dún an uchta’’ from the local topography, meaning ‘a fortified place on the breast (of the hill).’

The denomination of land within which the dún lay would appear to have been referred to up to at least the mid seventeenth century as ‘Down mcMearan,’ ‘Downemickmeneran,’ ‘Dwnmacmerran’ or variants thereof.[i] In the late medieval and early modern period it comprised one quarter of land and the site of the dún was of sufficient significance to give its name to the parish within which it lay.[ii] On Mercator’s Atlas map of County Galway dating from 1636 the site or area about the site was identified, south of the settlement at Clonfert, as ‘Donought.’ Following the acquisition of a large estate in the vicinity by the Cromwellian Captain John Eyre in the mid seventeenth century and the creation of a demesne about his new mansion house, the denomination known as ‘Down mcMearan’ was one of a number that were absorbed into the modern townland of Eyrecourt Demesne. The placename ‘Donanaghta’ survived as the site of the former church and as the name of the parish about Eyre’s new village of Eyrecourt.

The graveyard about the church ruins was shown on maps in the mid nineteenth century as ‘Doon grave-yard’ and continues to be known as such into the twenty-first. Little remains of the church structure but it was described as ‘standing in ruins in a grave-yard’ in the early nineteenth century when the antiquary P. O Keefe visited the site about late October or early November of 1838 when gathering information on the antiquities of the county. After engaging with the local populace O Keefe wrote that the old church was commonly called ‘Teampull a’ Dúin,’ a contraction of ‘teampall an dúin,’ the chapel or church of the dún.[iii]

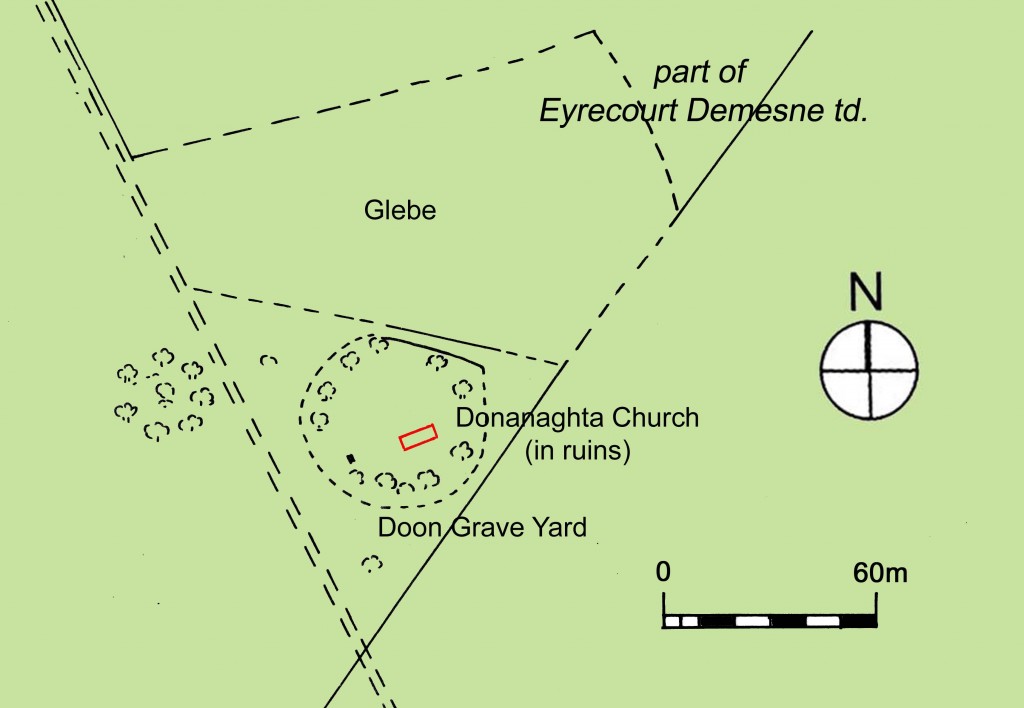

The site of Donanaghta church and grave yard in the mid nineteenth century, with the line of the external walls of the ruined church in red.

Mid nineteenth century maps show the church oriented on plan at a slight angle leaving it upon a south-west and north-east axis and was surrounded at that time by a sub-circular boundary. Later maps show the walls on an east-west axis, which corresponds to the orientation of the only surviving section of wall on site. Adjacent to the graveyard and to its north lay a small area of land identified as ‘glebe’ land and, while indistinct, it is possible that a small built structure or object lay within the sub-circular enclosure and directly on axis with the church, across from its western gable. No such object is evident in later maps from that century.

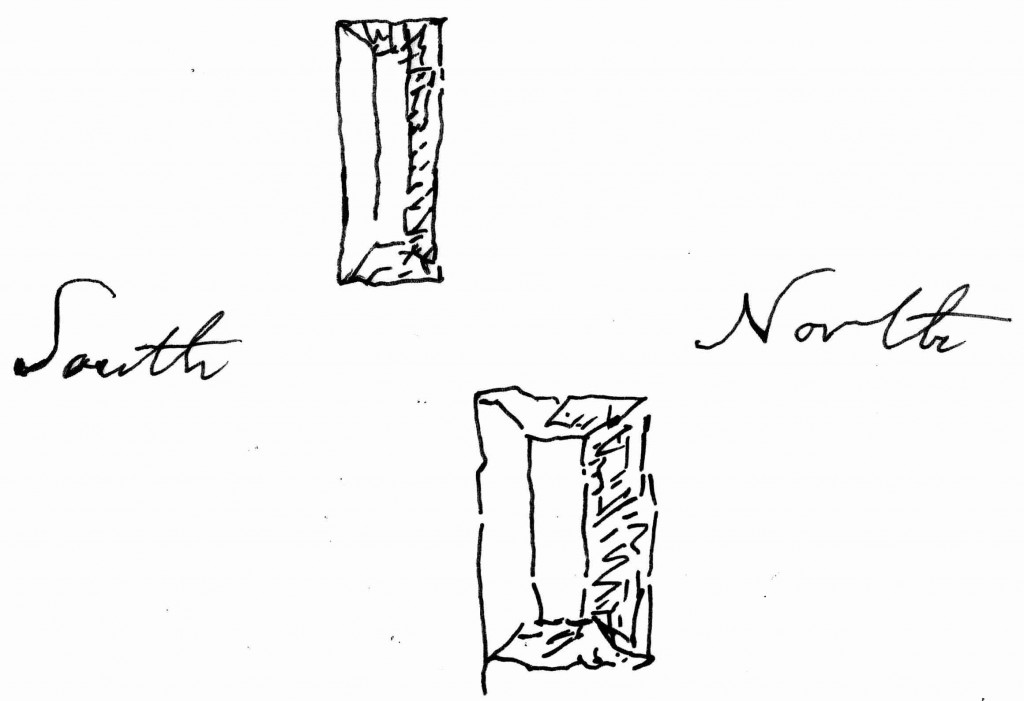

Of the then remaining structure in 1838 O Keefe wrote that the west gable ‘is nearly perfect’ and upon that gable were ‘two rectangular windows of the lancet form’ which he sketched for his correspondent.[iv] O Keefe’s sketch shows one window higher than the other but with insufficient space between the two to suggest that the higher may have served a first floor room. However, it has been pointed out that O Keefe’s sketch may not have been accurate or their position relative to one another accurate and in that event the higher window may have served a loft area over the western end of the church.

Tracing by the author from a copy of O Keefe’s sketch of the windows in the west gable. The upper window he described as ‘about 3 1/2 feet high and 6+ inches wide outside and the lower about 2 feet by 7 1/2 inches, being battered on the Northern side.’

Although O Keefe described the ‘south side-wall’ of the church as exhibiting a large breach in the middle, the remaining sections of that wall he believed appeared to have retained their original height. As no door opening existed in the west gable, it is likely that the entrance door was located at the western end of the south wall, in common with a number of other churches of this period. The east gable he described as ‘completely down’ and the ‘north side-wall’ as ‘running’ ‘nearly the entire length being battered at the top.’ He gave the length of the structure on plan as ‘about fifty five feet and the breath about twenty three feet.’[v]

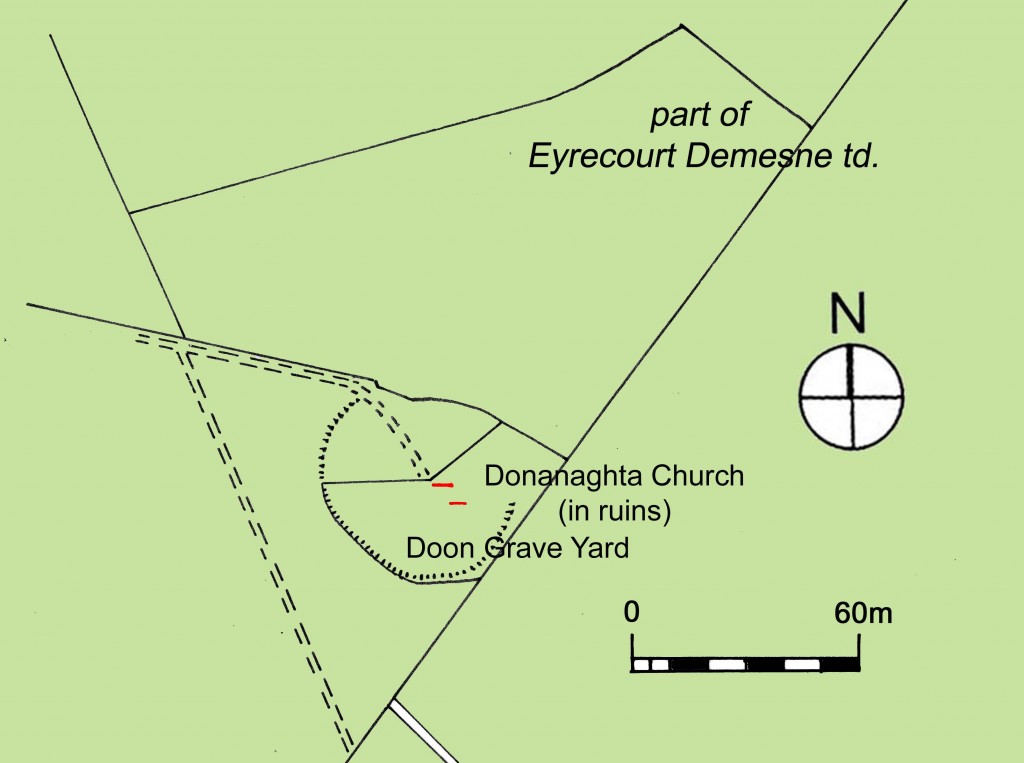

The site of Donanaghta church and grave yard showing what appears to have been only two remaining sections of the external walls of the church in red.

Only sections of the two church side walls appear to be standing within the sub-circular enclosure on late nineteenth century maps. The remaining section of the north wall had fallen by the late twentieth century when a State training agency undertook works on site to the remaining section of the south wall about the 1980s. On this occasion the works resulted in that section of wall being given a gable-like appearance with slate coping. No evidence of a batter is evident from the surviving wall, which is approximately 6.4m long x 0.7m wide. Against the south face of that wall a new narrow stone wall was constructed containing a niche to display a Marian statue.

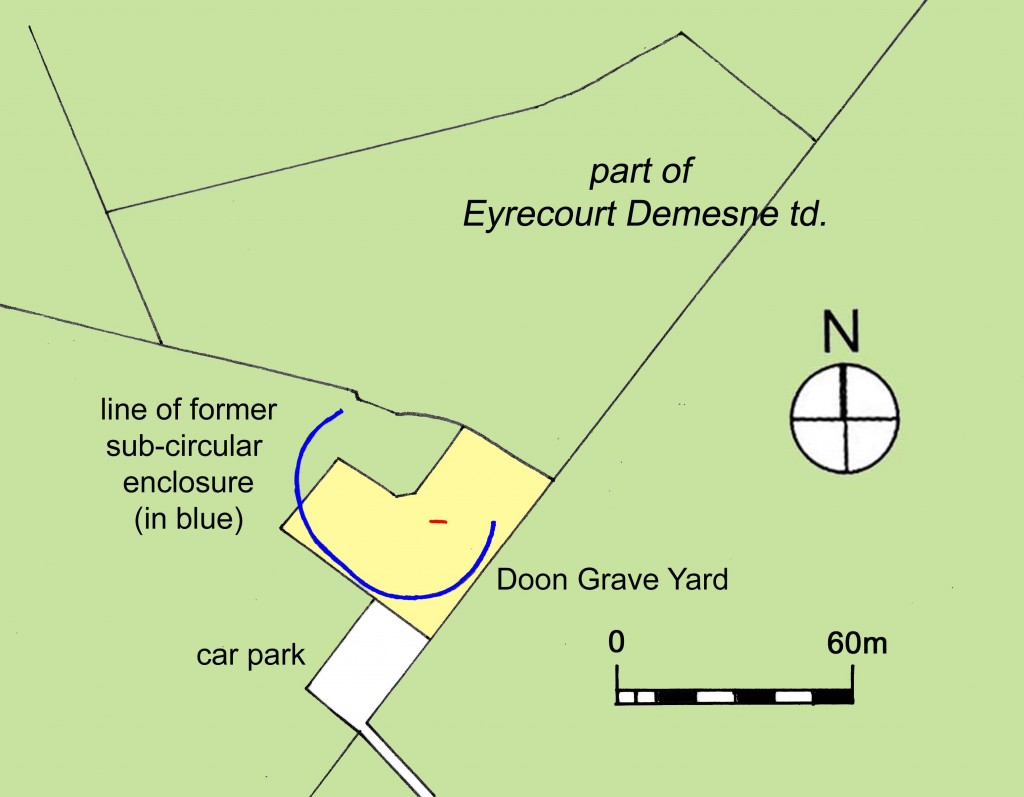

By the mid or late twentieth century new boundary walls were constructed to contain the graveyard surrounding the ruined church. The new walls ignored the previous line of the sub-circular enclosure and left areas of the former enclosure outside of the new graveyard boundary.

The remaining section of side wall following significant alterations in the late twentieth century, including the re-shaping of the wall to form a gable-like appearance.

The re-shapen side wall in the background, viewed from the east.

The site of Donanaghta church and grave yard showing the remaining section of side wall in red, the grave yard contained within modern boundary walls in yellow and the line of the former sub-circular enclosure in blue in relation to the new boundary walls.

Donanaghta was one of three dúnta or strong fortified places and seventeen townlands, according to the seventeenth century Registry of Clonmacnoise, that Cairbre Crom, ancient chieftain of the territory of Uí Maine or Hy Many, reputedly bestowed upon the religious foundation of St. Ciaran of Clonmacnoise.[vi] Cairbre Crom was regarded in the Gaelic manuscripts and pedigrees as the sixth century ancestor of the O Kellys, Maddens, Egans, Kennys, Treacys, Larkins and many of the families of east Galway and south Roscommon and while the Registry significantly post-dates the alleged bestowal by him of the site at Donanaghta, it would suggest that the site was regarded as having an ecclesiastical use from a very early period.

By the mid or late medieval period the priest attached to Donanaghta parish was provided by the canons of the Augustinian abbey of St. Mary’s de Portu Puro at nearby Clonfert. That many of the canons and priests serving at Clonfert and Donanaghta were drawn for the most part from many of the native Irish families long established in the immediate vicinity is evidenced from an ecclesiastical case involving the proposed removal of one canon and his replacement by another at Donanaghta about 1435. In early October of that year the Papal authorities wrote to the Abbot of Abbeygormacan and Thomas O Cormican, a canon of Clonfert, mandating them to ‘collate and assign to John Olorcayn, an Augustinian canon of St. Mary’s de Portupuro in the diocese of Clonfert, priest, the perpetual vicarage, wont to be governed by a canon of St. Marys, of Dunnanochta in the said diocese, value not exceeding 2 marks, void at the apostolic see.’[vii] The vicarage had been held by Dermit Maccuolachayn and after his death had been detained improperly ‘without canonical title’ by Malachy Ohurayn, a canon of the same abbey of Clonfert.

It was common in the medieval and late medieval period for parishes often to have had their priests or clerics appointed from those families whose ancestral lands lay within or near that parish, individuals from the family group thereby deriving the income from the benefices of that office. At the time of the Visitation of the Diocese of Clonfert in the late 1560s by the then Bishop, Roland Burke, the wider O Cormican family group provided the greatest number of clerics of any single family name to offices within the diocesan Church. At least five men of the name were then holding offices or derived benefices, with Maurice O Cormican serving at that time as vicar of ‘Dunnochto.’[viii]

In 1488 the Pope united the abbey of Clonfert to the bishopric but this was not put into effect for some time and it would appear that the bishops of Clonfert did not derive an income from the same abbey until the late sixteenth century.[ix] In 1543, as the officials of King Henry VIII began the suppression of monasteries and the confiscation of their property, Roland Burke, Bishop of Clonfert, succeeded in obtaining a grant from King Henry VIII uniting the abbey to the bishopric.[x] Bishop Burke did not, however, surrender the abbey at Clonfert to the King and Henry O Cormican, abbot of the monastery, retained control of ‘the lands and the temporalities and the spiritualities’ of the abbey until his death.[xi] The lands associated with the abbey at that time amounted to six quarters of land, all of which formed the modern townland of Abbeyland Great in the parish of Clonfert, to the immediate east of Donanaghta and included ‘the annual rent of the quarter of Down McMearan,’ about the church of Donanaghta.[xii]

When Henry O Cormican died about 1561 a dispute arose between the Bishop and others concerning the profits of the abbey, which lasted for five or six years until William O Cormican travelled to Rome in 1567 and obtained the abbacy from the Pope. Bishop Burke and William O Cormican thereupon agreed to divide the profits between them. William died in 1571 and the Bishop thereafter was the sole beneficiary of the profits until his death in 1580.[xiii] Following the death of Bishop Burke, Stephen Kirwan was appointed by Queen Elizabeth I as Protestant Bishop of the diocese.

It is unclear when the church ceased as a Roman Catholic place of worship or if it was used as a place of worship by the Protestant Church for a period in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century prior to the construction by Captain John Eyre of a small Protestant church near the west entrance to his demesne in the late 1670s. However, with the exception of a small number of Protestants who settled in East Galway about the early decades of the seventeenth century prior to the 1641 Insurrection there would appear to have been a paucity of Protestant families established in the vicinity of Donanaghta before Eyre ‘brought several Protestant families together’ ‘in order to promote and encourage an English plantation there’ before 1679.[xiv]

[i] Shane roe mcTeig of Dwnmacmerran was among those pardoned in 1586 (Fiants Eliz I). One Donogh boy mcHugh of Downvickberra was among those pardoned in 1585, while Richard mcDonnogh boy O Madden held land in the townland about 1641, as did Donnogh Mc Brassell O Madden of Lismore and Teige Mc Downy Mc Teige and John Duffe Mc Rory O Madden, when it was given as ‘Doonecunaram’, parish of Doonanoughta. John Lawrence of Ballymore, about 1618, held a third quarter of Downemickmenaran. In the mid 1650s Donagh O Madden was ordered to transplant from ‘Downimarrane’ by the Cromwellian authorities and allocated 28 profitable Irish acres in the parish of Ballynakill in Co. Galway. (Siminton, R.C., The Transplantation to Connacht 1654-1658, Irish Manuscripts Commission, 1970, p. 159.) In the mid seventeenth century Books of Survey and Distribution the denomination is called ‘Doonecunarum alias Doone Mc Nerane.’

[ii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. 195.

[iii] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, letter no. 4, Loughrea, dated 3 November 1838.

[iv] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, letter no. 4, Loughrea, dated 3 November 1838.

[v] O Donovan, J. and others, Letters containing information relative to the Antiquities of the County of Galway. Collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1839. Vol. 2, letter no. 4, Loughrea, dated 3 November 1838.

[vi] O Donovan, J. (ed.), Registry of Clonamcnoise, with notes and introductory remarks, Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1857, pp. 440-460.

[vii] Tremlow, J.A. (ed.), Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 8, 1427-1447, 1909, p. 542. Laterna Regesta 330: 1435-1436.

[viii] McNicholls, K.W., Visitations of the Dioceses of Clonfert, Tuam and Kilmacduagh, c. 1565-67, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, 1970, pp. 144-157.

[ix] Egan, P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 52.

[x] J. Morrin (ed.), Calendar of the Patent and Close Rolls of Chancery of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, Vol. I, Dublin, Alex, Thom & sons, 1861, p. 87.

[xi] Blake, M.J., A note on Roland de Burgo alias Burke, Bishop of Clonfert; and the Monastery “De Portu Puro” at Clonfert, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, No. iv, pp. 230-232; Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 52.

[xii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. 192; Blake, M.J., A note on Roland de Burgo alias Burke, Bishop of Clonfert; and the Monastery “De Portu Puro” at Clonfert, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, No. iv, pp. 230-232; Simington, R.C., The Transplantation to Connacht 1654-58, Shannon, Irish University Press, for the I.M.C., 1970, p. 160. The six quarters appear to have been those of Killine, Rath, Corragh, Ballyhugh, Claggernigh and the two half quarters of Gortnaskemore and Clonesmucke, all of which later composed the modern townland of Abbeyland Great in the parish of Clonfert, at a distance south of the abbey. A number of these denominations occur in Petty’s mid seventeenth century map of the area about the later Abbeyland Great.

[xiii] Blake, M.J., A note on Roland de Burgo alias Burke, Bishop of Clonfert; and the Monastery “De Portu Puro” at Clonfert, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, No. iv, pp. 230-232.

[xiv] 15th Annual Report of Records of Ireland, p. 358.