© Donal G. Burke 2014

According to tradition, many of the existing tribes and peoples who inhabited the region that would later be known as east Galway were subjugated by a tribe who established their dominance there by about the end of the fifth century led by one Maine mór, son of Eochaidh feardaghiall.[i] Maine mór and his descendants established a petty kingdom, covering much of the later east Galway named from their progenitor as Uí Maine, later Anglicised as ‘Hy Many.’ The principal family descended of a senior line from this Maine mór was the O Kellys, the head of which family provided the kings or chieftains of Uí Maine.

Within the greater Uí Maine kin group an off-shoot branch of the senior line came to be known as the the Síol Anmchadha, the ‘seed’ or progeny of Anmchadh,’ ancestor of the branch.[ii] The principal family of those that formed this offshoot branch, the O Maddens, came to rule a part of the eastern region of Uí Maine, to be known thereafter from their common ancestor as Síl Anmchadha or ‘O Maddens County’ and later as the barony of Longford in east Galway.

The learned historian Rev. Patrick K. Egan at one time gave the O Horans as ‘a family of the Uí Maine.’[iii] However, while they were a family of note in the region, no specific descent from the Uí Maine was given for the O Horans in such genealogical manuscripts as the Book of Lecan or in the seventeenth century antiquary Dubhaltach MacFirbisigh’s ‘Great Book of Genealogies.’

The Book of Lecan, a Gaelic manuscript compiled in the early decades of the fifteenth century related the descents, offices and services of various families of the Gaelic territory of Uí Maine or Hy Many in east Galway. The manuscript described the head of the O Horan family as ‘Ua Urain Cluana Ruis’ and holding the office in the ancient hierarchy of the territory of ‘uireasbaidh’ to the ‘arch-chief,’ which the nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan translated as ‘distributor’ or ‘butler’ to the O Kelly chieftain of Uí Maine.[iv]

O Donovan equated the ‘Cluain Ruis’ of the manuscript with the later parish of Clonrush in South East Galway, on the border of County Clare and at the southerly extreme of what was given as the early confines of the territory of Uí Maine. The Gaelic territory was said to extend south to the river or lake of Graney in what is now the modern County Clare, which would appear to include the area about Clonrush.[v] (The parish of Clonrush itself lay within the county of Galway until the nineteenth century and was thereafter included as part of County Clare.)

Given the rise of the O Madden chieftaincy of Síl Anmchadha in the eastern region of Uí Maine and the contraction in size of the effective area of Uí Maine and the power of the O Kellys following the Anglo-Norman conquest in the early thirteenth century, distancing Clonrush and much of what had been the former southern area of Uí Maine from the O Kellys, the services and offices outlined in the Book of Lecan may significantly predate the compilation of this manuscript. It is uncertain but thought possible that many of the tracts contained therein may have been compiled from earlier manuscripts, making the dating of the offices, rights and services of the various families uncertain.

If O Donovan is correct and the O Horans were settled at one time about this Clonrush, it would imply that the tract may have been significantly older than the Book of Lecan itself as the O Horans, by the late medieval period, were established much further north, about the later parish of Fahy in Síl Anmchadha, the territory ruled by the O Madden chieftains.

The area given as ‘Balli y hurain,’ the ‘settlement or township of Uí hOdhrain’ in the Episcopal Rentals of the Diocese of Clonfert of circa 1407 is an early reference to the lands associated with the family as a whole within the diocese. [vi] It is likely that this ‘Ballyhoran’ equates with the area described as the parish of ‘Moynterorrane’ or muintir Uí Odhrain (ie. ‘the people of O Horan’) containing seven quarters of land in the 1585 inquisition of what was O Madden’s Country, the barony of Longford in east Galway and reflected the traditional lands of the O Horans in the medieval period.

Medieval ecclesiastics

In the medieval and late medieval period, many of the offices and benefices of the Church in the diocese of Clonfert were held by members of the most prominent families of native Irish and Anglo-Norman origin, such as the O Kellys, Burkes, O Maddens, O Treacys, O Lorcans and O Dolans. The same families were also predominant in the local monasteries such as Clonfert and Clontuskert Omany. The O Horans also had a long tradition of service to the Roman Catholic Church, providing numerous secular and religious clerics to Clonfert and surrounding dioceses throughout the medieval period.

One of the name, Malachy Ohurayn, was a canon of the Augustinian monastery of St. Mary’s de Portu Puro at Clonfert in the mid fifteenth century. The Papal authorities at Florence decreed that John O Lorcan, another canon of Clonfert Abbey, should be assigned the perpetual vicarage of ‘Dunnanochta’ about 1435 or 1436. It was taken as the right of the Clonfert Abbey to govern that nearby vicarage and the Papal authorities decreed that this Malachy should be removed to facilitate the new appointment, the same Malachy having possessed that vicarage for more than two years ‘without any canonical title.’[vii]

He appears to have been the same Malachy, who held the perpetual vicarage of the parish church in Loughrea in the mid fifteenth century. As was the case at Donanoughta, it was acknowledged at that time that the abbey at Clonfert also held the right to provide the vicar to that particular vicarage at Loughrea. By 1459 O Horan was in ill health and one Thady O Hanrahan, a canon of the Augustinian monastery of Lorrha reported to the Pope that O Horan had ‘become a paralytic, so that he cannot without standing and danger administer the sacraments to the parishioners.’[viii] O Hanrahan further accused him of simony and of having ‘delapidated the goods of the vicarage, to the pernicious example of the said parishioners, who therefore absent themselves from the said church and go to other churches or monasteries in order to receive the said sacraments and hear divine offices.’ The Papal authorities responded from Mantua in June of 1459 and instructed the dean and two canons of Clonfert to have O Hanrahan accuse O Horan in their presence and if he were to do so, and they find the accusations to be true, they were to remove O Horan and assign the vicarage to O Hanrahan with the provision that, as the vicarage was the preserve of the canons of the Clonfert abbey, O Hanrahan would be required to be transferred from the Lorrha abbey to the monastery de Portu Puro.

One of the most noted ecclesiastics of the name was Donagh O Horan (known also by his Latin name Donatus), who served as the last Roman Catholic Dean of Clonfert in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. He served as Dean of Clonfert from at least the death of Roland Burke, Bishop of Clonfert in 1582, during a period in which the Protestant Church of the Tudor monarchs was attempting to gain control over the existing Church structures. The Clonfert historian Rev. Patrick K. Egan believed that O Horan was the last Roman Catholic who enjoyed the temporalities of the deanery. Following an inspection of the diocese by Protestant Visitators in 1591 he was deprived of the office. Despite being removed officially by the Queen’s representatives he appears to have still held a position of authority in the local Church as the Queen only appointed his Protestant successor in 1597, the office being then described as vacant upon the death of Donagh.[ix]

Sixteenth century

In the sixteenth century, services and customs were due to the O Madden chieftain from the principal branches and sub-septs of the O Maddens themselves within Síl Anmchadha and from the four main constituent families within the lordship; the O Horans, MacCoulahans, O Treacys and O Larkins. Of those constituent families, the O Horans appear to have held the highest status. Their patrimony was a well-defined area within the territory of the O Maddens, larger than any other of the constituent families. In early 1570, when Richard Burke, 2nd Earl of Clanricarde raided deep into Síl Anmchadha, and despoiled the O Horan lands about Fahy and Meelick, the area was referred to in a contemporary English dispatch as ‘O Horan’s Country’.[x]

‘Cornelius or Conogher roo (ie. ‘roe’ or ‘ruadh’, the red-haired) O Horan of Fahye in Sillamchi in Co. Conaghe, gentleman’ and Connor O Horan his son were listed ahead of Rory McCollo O Madden of the nearby Brackloon castle and a number of other individuals in a pardon issued to them about 1570 or 1571.[xi] ‘Hugh O Howran of Fahe’ was listed with a number of the MacSweeneys as being pardoned in another set of such pardons in the year 1570.[xii]

The O Horan castle at Fahy

In 1574 the head of the family, identified only as O Horan in a detailed list of the chief men and their residences of the barony of Longford, was given as resident at ‘Faheioran’. From an early date a castle or tower house was erected at Fahy in the quarter of Carrowanclogha.[xiii] No remains of this tower house appears to have survived by the late nineteenth century, but reference is made in the late eighteenth century to the ruins of a castle located close to the public road, on the opposite side of the road to the seat of the Hamilton family of Fahy, at a distance of almost two miles from the village of Eyrecourt.[xiv] As the later Hamilton seat appears to have been known as Greenfield in the modern townland of Fahy, on the right hand side of the public road as one travelled from Eyrecourt to Portumna, this would suggest that the remains in question were located in the modern townland of Fahy, not distant from the entrance to Greenfield or in that narrow part of the adjoining modern townland of Tullinlicky.[xv]

The ruins of an old church and graveyard were extant in the late nineteenth century in the same vicinity, close to the road, on the modern townland border between Fahy and Tullinlicky and it is unclear if the eighteenth century author was confusing the ruins of this church for that of a castle, or if the castle ruins and church ruins co-existed in close proximity. John O Donovan, passing through this area in the late 1830s noted only the presence of the ‘old church of Fahy’, ‘a small rude church with all its features destroyed and presenting nothing of interest to the antiquarian.’ He stated that at that time there was ‘nothing else of interest in the parish,’ suggesting that he saw no ruins of a castle in the vicinity at that time.[xvi] It is noteworthy, however, that what may appear to have been a residence is shown in close proximity to, and to the east of, the site of a church in the parish of Faghy on Petty’s late seventeenth century map of the barony of Longford.

Within their territory, adjoining Carrowanclogha, lay the area known as Tullinlicky or ‘tullach an leiche’, the hill of the stone slab’. A combination of factors, geographical location, local folklore and the status of the O Horans within Síl Anmchadha, would suggest this to be a possible reference to the ancient inauguration site of the O Madden, and indicating that the O Horans may have played a foremost role in the inauguration of the O Madden chieftain.[xvii]

Throughout the sixteenth century the Crown’s officials and soldiers in Ireland strove to reassert royal authority across the country, bring the Gaelic chieftains and the Gaelicized lords of Anglo-Norman descent under the control of the monarchy and replace Gaelic laws and customs with those of England. As that century progressed the authority of the Crown grew and by 1585 an agreement was reached between the principal men of Connacht and the Crown whereby they would abolish the Gaelic titles of authority and system of landholding and to hold their land from the Crown under English law.

At an inquisition taken into the ownership of property and dues in the barony of Longford on 30th August 1585 as part of the Composition agreement, the head of the O Horans was given among the chief men of the barony as ‘Connor oge o fahy.’ The Connor Og is more correctly Connor óg O Horan of Fahyhoran, identified as ‘chief of that name’ in a pedigree of the Maddens of Derryhiveny, with whom he was connected through the marriage of his daughter Fenola with John Madden of Derryhiveny.[xviii] The seven quarters of the parish of Moynterorrane or ‘muintir Uí Odhrain’ was held as an area unto itself in the 1585 inquisition of the barony and excluding the quarter of Feabegg, which was regarded separately in the 1585 indenture of O Maddens country, Moynterorrane appears to have corresponded to the parish of Fahy as it stood in the middle of the following century.

Among those issued a pardon by the Crown in 1585 were William O Horan mcFarres O Horan and Teige reoghe McFarres O Horan, both described as gentlemen and ‘of Faye’ and one ‘Wony duff O Horan of Lysfadda, cottier.’ The following year one Edmund O Horan with no address given was among those pardoned.

Early seventeenth century

The head of the family, Rory O Horan of Fahy, entered into a deed dated February 1592 with Rory McCollo O Madden of Brackloon, whereby Rory O Madden conveyed his lands at Brackloon, Clonkea, Cagalla, Killoran and Clonashease, all in the parish of Clonfert, to Roger or Rory O Horan of Fahy and his heirs in perpetuity, to use of the said Rory for the duration of his life, and after his death to use of his son Ambrose maol.[xix]

While various prominent members of the Horans family are buried at the friary church of the Franciscans at Meelick and their deaths recorded by the friars, members were also buried at nearby Clonfert. The gravestone of one Roger Horan, buried at Clonfert, was affixed to the south wall of the nave of the Cathedral during repair work to Clonfert Cathedral. Lord Walter Fitzgerald, writing not long after the repair work was undertaken, gives the inscription on this slab as ‘Hic Iacet Dns Roger Horan Precipvesve natio-s hvc tumulu sibi ac postereis hic suis fecit fieri Ano Doni 1616.’

The 1616 Horan gravestone, affixed to the interior of the south wall of the nave of Clonfert Cathedral.

At the start of the seventeenth century the parish of Fahy, almost in its entirety, was still held by the O Horans. The head of the O Horans, Rory O Horan of Fahy, son of Connor, was the largest individual landholder, with lands in Fahy and the later parish of Meelick. He held half of the land in the quarter of Carrowanclogha, ‘with the castle there’, which would appear to have served as his principal residence.[xx] He also held half the lands of the quarters of Carowmorederryhoran and of Carownafinoigy, of Camus, half a cartron in Gortskehy and a cartron of Lismoyfadda and held the quarter of Tully. He also held a half cartron of Kilmacshane in the parish of Clonfert. His son John O Horan of Ballynykilly held half of the two quarters of Ballynakill in the parish of Clonfert.[xxi]

A considerable portion of land across the family’s ancestral lands at that time were held jointly by Edmund O Horan of Fahy and Dermot O Horan of Camus, with both holding land in Carrowneclogha, Camus, Carowmorederryhoran, Carownefinoigy, Ballyeighter and Meahanagh. Edmund of Fahy also held three eighths of the quarter of Carowanmeanagh separately in his own right.[xxii]

On a level almost with the last two individuals, one Cahir O Horan of Fahy held lands across much of O Horans country, with land in Carrowmorederryhoran, Carrownefinoigy, Ballyeighter, Meahanagh, and a small portion, one eighth of a cartron in Carrowneclogha.

Donagh mcFeriagh O Horan of Iskertealla held a lesser amount of land in Carrowneclogha, Carowmorederryhoran, Carownefinoigy, Ballyeighter and Meahanagh.

The quarter of Moyoure was held separately, as it was divided solely between Dermot mcDonagh O Horan of Carowmoyoure, who held one half of that quarter and Connor oge O Horan mcDonagh and Teige reogh O Horan of Moyoure, the latter two jointly holding the remaining half. None of these three O Horans appear to have held lands elsewhere in O Horan’s country. Dermot O Horan of Moyower was married to Margaret Carroll by whom he had a daughter, Sara. He died on the 30th April 1618.[xxiii]

Sara ny Dermot, daughter of Dermot O Horan, described in 1632 as ‘late of Moygiore (Moyower), in the county of Galway,’ was granted an ‘Ouster-le-main’ whereby she had lands which would appear to have been her inheritance delivered into her possession legally in March of that year and would appear to be daughter of this Dermot son of Donagh of Moyower.[xxiv]

Elsewhere, Conor McDermot O Horan of Derrymckening held a cartron and a half cartron respectively of Carrowmarilaghta and Carrownekoille.

Those individuals were the most senior of the O Horans in the early seventeenth century, as reflected in their portion of the overall family lands with a number of less senior landholders holding smaller sections such as Flan O Horan of Lismoyfadda holding one twelfth of the three cartrons of Lismoyfadda and Conor mcOwen boy O Horan, Donnell McHugh O Horan, Awly boy mcTeig O Horan and John mcTeig O Horan of Lismoyfadda, gentlemen, all four jointly holding three twenty fourths of the three cartrons.

Rory O Horan died on the 24th June 1632 ‘captain of his sept (‘suae nationis capitaneus’), old and full of days’ and his son John became the principal landholder of the family.[xxv] In the late 1630s, as ‘John mc Rory mc Connor O Horan’ he held one of the two quarters of Carrowcloghy Tullaghanelicky alias Ballyeghnagh in the parish of Fahy, the rest of that denomination held for the most part by various junior O Horans. In the adjoining parish of Meelick he was proprietor of the quarter of Tully, a half quarter of Derryhoran and a portion of Camus, while in Dononaughta he held land in Lisfinny and in the parish of Clonfert the greater part of the two quarters of Ballynakill and of Fynagh.

Loss of the O Horan ancestral lands

The O Horans lost possession of their lands in Fahy as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century which were subsequently confirmed on a number of landholders, among them, Clanricarde, the Cromwellian Captain John Eyre and, through their later acquisition of Henry Cromwell’s estate, the Earls of Cork and Arran. John mcRory mcConnor O Horan found himself allowed 69 profitable Irish acres in the parish of Donanoughta.[xxvi] ‘John Horan of Fahy’ was given as head of family and one of the dispossessed landowners in 1664 whose lands was confiscated by the Cromwellian authorities and whose names were submitted to the Lord Lieutenant in that year for consideration for restitution.[xxvii]

Following the turmoil of that period and the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, an Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time. The new monarch was slow to undo the earlier Cromwellian settlement of land, as he himself was a Protestant King of a Protestant England deeply suspicious of Roman Catholicism. There was also a strong Protestant interest group composed of certain newly arrived Protestants and those longer established in Ireland who did not wish to see Roman Catholicism rehabilitated. Unable to adequately balance the interests of the dispossessed and those fearful of losing their new estates and with insufficient land to placate all, the Act of Settlement would leave many disenchanted.

The King declared that all those Cromwellian adventurers and soldiers would be left in possession of their estates with the exception of those the monarchy regarded as particular enemies, such as those directly involved in the killing of the king’ father King Charles I. Those Roman Catholics found innocent were also to be reinstated to their lands and the Cromwellians then in possession of that Catholics holding was to be compensated elsewhere. The solution proved unsatisfactory to many but allowed for many Cromwellian landholders settled in Ireland to retain the majority or part of their estates.

Under the Act of Settlement the former O Horan lands in the parish of Fahy were confirmed in the possession of others. Only two Horans were recorded as confirmed lands by grant under the Act of Settlement; John Horan, with lands of 235 profitable Irish acres in the parishes of Aughrim and Clontuskert, and Roger, with lands of 48 acres in Ahascragh and Killoran.[xxviii] Immediately subsequent to the upheaval in land ownership in the Cromwellian period, however, one of the most senior, if not the senior-most line, of the Horans appears to have been located about the parish of Abbeygormacan.

No Horan was recorded as having been granted lands in that parish under the Act of Settlement but the recipient of a large part of the lands later associated with the Horans in Abbeygormacan were granted under the Act to Nicholas Hannin, whose family had been significant landholders in that area prior to the Cromwellian period. As Cornelius Horan, who flourished in the latter decades of the seventeenth century was described as ‘of Abbeygormican’ and was married to Catherine Hannin, it is possible that the Horans may have been associated with these lands through marriage with the Hannins. While Catherine did not appear in a pedigree maintained in the records of Ulster King of Arms of the wider Hannin family of Abbeygormacan, notes survive in Betham’s Genealogical Abstracts relating to the will dated 1712 of James Hannin of Iskerboy, County Galway which give Cornelius Horan as the testator’s brother-in-law. Cornelius Horan’s wife Catherine, therefore, was daughter of Hugh O Hannin of Iskerboy in the parish of Abbeygormacan and sister of both James, who died without issue in 1712 and Murtagh Hannin of Sunnagh, Co. Galway.

Eyre’s Agent

Charles II was succeeded on the English throne by his brother, the Roman Catholic King James II, in 1685. The accession of a Catholic king caused great anxiety among the Protestant community, while the Irish Catholics heralded the arrival of the new king as the redeemer of their lost estates and power, their first glimmer of hope after decades of despair and frustration. Influenced in part by some of his Irish favourites at court, laws oppressive to Catholicism were relaxed by the king, and it appeared that Catholics could once again be appointed to positions of power in the realm. Concern was such with the shifting balance of power that a group of Protestants rose up in England against King James, under the Protestant Duke of Monmouth. The rebellion was crushed and those responsible were dealt with in a brutal manner.

One of the Horans served in the late seventeenth century prior to Monmouth’s Rebellion as the Land Agent of Captain John Eyre at Eyrecourt. His place, however, within the wider family is uncertain but given the position it would appear that he was at least a relatively senior member of the name.

The rising in England had repercussions for the heir to the Eyrecourt estate of Captain John Eyre. On the death of Eyre in April of 1685 his young son and heir John Eyre returned to Ireland. Upon his return he found himself the subject of rumours, claiming that he had been hanged for participating in Monmouth’s rebellion. In addition, it was alleged his brother was ‘in the head of three score and ten horse, for Ye Duke of Munmouths use’. The source of the rumours, he discovered, was his fathers’ former agent, John Horan. The agent denied being the source, claiming it to have been another individual whose identity he could not reveal. John Eyre’s brother brought the matter before the courts and Horan was indicted for ‘scandalous words and spreading false news’. Though he admitted his guilt, Horan was acquitted; the jury believing the rumours were not intended as malicious. John Eyre appealed to the Duke of Ormonde for advice. Horan, he claimed, was now intent on ruining him and his family and believed he would swear to anything to bring about Eyre’s demise. Behind Horan’s actions, he further claimed, was a debt of five hundred pounds owed by the agent to Eyre’s father, and for which John Eyre was at that time suing Horan. With the political tide turning in the country, Eyre, with his family, fled Eyrecourt and sought the relative safety of England.[xxix]

King William and Queen Mary

Alarmed by the increasing Catholic influence and at the birth of a Catholic heir to the king, the still powerful Protestant interest in England deposed King James, and offered the crown to his Dutch son-in-law, the Protestant Prince William of Orange and his wife Mary. The English Parliament declared James’ throne vacated in December 1688 and his daughter and son-in-law jointly crowned King William III and Queen Mary II. The Irish Catholics rose up in support of King James, and an army was sent by the French King to reinforce James’ Irish supporters, the Jacobites.

In March 1689 James landed in Ireland to head his army here, hoping to regain his throne through Ireland and a Catholic-dominated Parliament was set up in Dublin. The Irish Catholics hoped to recover much of their former lands that they were denied under the settlements after Charles II had been restored and the Irish Parliament declared many of the Williamites, supporters of William of Orange, outlaws and their lands were to be confiscated as such. King William arrived early in the following year with his Dutch and English army, and so began the war of the two kings.

The leading Roman Catholic families responded enthusiastically to the cause of James II and six regiments were raised for the king in 1688, four of which remained active throughout the war; those of the Earl of Clanricarde, his brothers Colonels Lord Bophin and Lord Galway and that of Dominick Browne.[xxx] The officer’s ranks in the Galway regiments were swelled with members of the most prominent Catholic county families. Among those persons from about the Fahy and Meelick area who served the Jacobite cause in the War of the Two Kings were Captain Cornelius O Horan and Lieutenant Roger Horan of Abbeygormacan, who both joined the infantry regiment of Ulick Colonel Lord Galway, their ranks indicating their status among the families of the region and relative to one another.

The defeat of the Jacobites and the articles of Limerick and Galway

The war concluded with the defeat of the Jacobite army and the signing in October 1691 of the Treaty of Limerick. Many prominent Irish Jacobites faced the prospect of losing their lands under the new government of King William and Queen Mary. The estates of those deemed outlaws and traitors in February 1688 were to be vested in thirteen Trustees and the same estates to be sold.[xxxi] A large number, however, were eligible to benefit from the ‘articles of Limerick and Galway’ that formed part of the Treaty. The terms of the treaty allowed the Jacobite soldiers and people holding out at Limerick and at Galway to either sail for France or remain in Ireland and submit to the new King. Those who submitted to the new Protestant King and Queen and were eligible to benefit from the articles were to be allowed to keep their estates intact and, if outlawed, pardoned. The hearing of cases of those seeking to avail of the articles was a prolonged affair, extending into 1699.[xxxii]

Following the defeat of the Jacobite interest, more than one thousand of the Irish Jacobites indicted and outlawed for ‘high treason beyond the seas’, many of whom sought service in the French army, were declared outlaws in many cases by default and their property subject to confiscation. Among those prosecuted for high treason beyond the seas was Roger Horan of Abbeygormacan, gentleman.[xxxiii]

Very few of those who applied to be rehabilitated under the Articles of Galway were rejected. One claim, however, that was rejected in December of 1698 was that of Captain Cornelius Horan of Abbeygormacan.[xxxiv] Cornelius remained in Ireland and maintained the family connection with the Franciscan friary at Meelick, being one of ten people to whom the friars there turned to preserve their chalices, vestments and books for future use when the government enacted the ‘Banishment of Religious Act’ in 1698 requiring Roman Catholic Bishops and religious to departed from Ireland before May 1st of that year. A lady identified only as the ‘Widdow Horan’ numbered among the other nine persons.[xxxv]

Among the other individuals to whom the friars of Meelick planned to entrust their valuables at this time was James Dillon of Rathingelduffe or Rath, near Birr in the King’s County, connected by marriage to the Horans. The eldest son and heir of Patrick Dillon of Rath, King’s County, seventh son of James, 1st Earl of Roscommon, James Dillon married firstly Elizabeth, daughter of John Veale, esquire by whom he had at least two sons and secondly Penelope Horan.[xxxvi] It would appear likely that it was through this second marriage that James Dillon and his descendants by both of his marriages would become intimately connected with the Meelick friary.

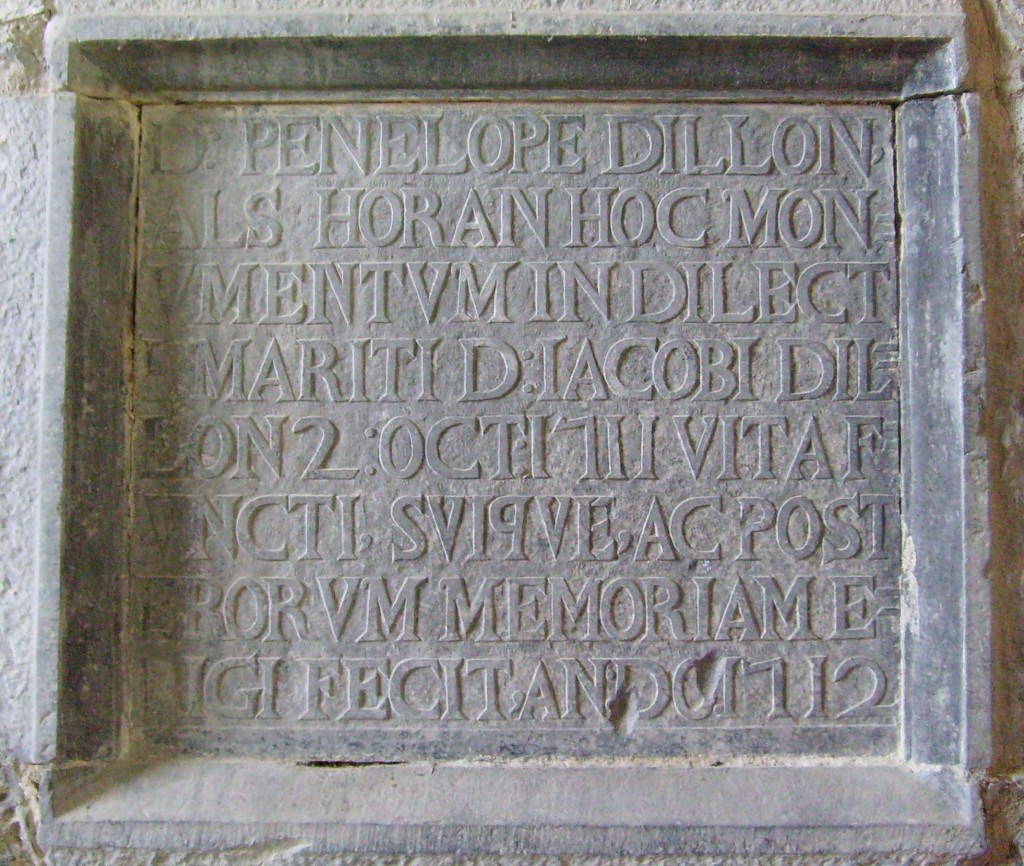

The Franciscans at Meelick described James Dillon as ‘a great benefactor’ and recorded his wife Penelope as a daughter of Cornelius Horan and Catherine Hannin. By Penelope Horan James Dillon had at least three sons and three daughters; Michael of Rath, Francis, James, Catherine, Mary (who would marry Edmund Hearn of Hearnsbrook, near Killimor) and Elinor or Helen (called ‘Nelly’ by her father). In Dillon’s will dated 29th September 1711 Dillon described one James Horan as his ‘dear brother (in-law)’ while a Cornelius Horan served as a witness to the sealing of the will.[xxxvii] Both his wife Penelope and brother-in-law James Horan, together with his eldest son by his first marriage, were appointed as executors of the same will. He left a legacy to the Meelick friary and when he died on 2nd October of that year, he was buried in the friary church. In the following year his widow had a mural memorial tablet erected in the choir of the church bearing the inscription; ‘D. Penelope Dillon, als. Horan hoc monumentum in dilectae mariti D: Jacobi Dillon 2: Oct 1711 vita functii, suique, ac posterorum memoriam erigi fecit an:do: 1712.’

The Dillon memorial tablet erected in the church of the former Franciscan friary at Meelick.

The Horan lands in Abbeygormacan in the eighteenth century

Despite the outlawry of Roger Horan and the rejection of Cornelius Horan’s claim under the articles, this Horan family still retained an interest in lands in Abbeygormacan. William Burke of Dublin City son of Colonel Richard Burke in a deed of 1713 undertook to influence his father to release lands in Iskerboy, Larga (Lurga) and elsewhere to James Horan of Dublin City, gentleman. Simultaneously both Hugh and Michael Hanyne, in a deed witnessed by one Gerard Hanyne of Dublin City, Esquire, undertook to release lands in Iskerboy, Larga and elsewhere to the same James Horan, which lands were previously occupied by the late James Hanyne, Esquire. In 1720 James Horan of Dublin City was involved in the leasing of 140 acres of land at Cappanaghlin (recte: modern townland of Cappanaghtan) and 50 acres at Kilknane, both in the barony of Longford and in 1728 in the lease of lands at ‘Culiny otherwise Cooloony otherwise Castletown, Liscoyle otherwise Liskele, Killbegg and lands at Gorteen as part of Drum and in Corbane and at Knockanicorragh, all, with the possible exception of Corbane in the parish of Abbeygormacan in east Galway. In 1730 James Horan, of the City of Dublin, gentleman, transferred property in ‘Eskerboy, Ballymahin, Cappaghtan, Lorga’ and ‘Gortmore’ in that parish to John Burke, of the Inner Temple, London, gentleman.[xxxviii]

This James Horan of the City of Dublin was son of Cornelius Horan and Catherine Hannin and brother of Penelope Dillon. He appears as such in a deed of 1738, which states that the then deceased Andrew Hearn of Hearnsbook in County Galway had previously obtained a judgement against the same James Horan and Andrew’s son Edmund of Hearnsbrook used this judgement as security in an agreement with Horan to repay the amount over several years. In 1738 Edmond Hearn affected a lease to James Horan of the City of Dublin, Gent., in case Edmond’s wife Mary Hearn otherwise Dillon, described as Horan’s niece, survive him she should be in a position to benefit from the agreement. Among the witnesses to the deed was one John Horan of Dublin City, in all likelihood the same John Horan, son of James of Dublin City, who witnessed another transaction in that same year involving his father and the lands in the parish of Abbeygormacan.[xxxix]

The friars managed to retain a presence in the Meelick area throughout the period and it was they who recorded the death on the 20th November 1726 of Captain Cornelius O Horan. Two days later he was buried in ‘his own burial place’ in the friary church. Three years later, the Meelick friars recorded the death in that year of Penelope, daughter of Cornelius Horan and Catherine Hannin, whom they described as ‘a great benefactress of this convent of Meelick.’ In their words, ‘she married first James Dillon, and being released from the law of her husband, after some years married Andrew Hearn. She was buried in our church first fortified by the sacraments of the Church.’[xl] Catherine Dillon (also known as Cate), Penelope Horan’s daughter by James Dillon ‘a virgin very devoted, given to fasts, prayers and vigils,’ died ‘carried off by a malignant fever’ in June of the same year, 1729 and was likewise buried in Meelick church with her mother. Joanne Horan, the ‘noble lady’ who, in March of 1753, left a legacy to the Meelick friars of five pounds with the requirement that they pray for a happy death for her, attend at her funeral rites and have a sung mass for the happy repose of her soul, was undoubtedly of the same most prominent line of the Horans.

This senior line of the Horans disappeared from the ranks of the landed families resident in east Galway about the eighteenth century. Their prominent status in the vicinity of Fahy and Meelick may be evidenced by the location of their burial place in close proximity to the high or ‘great’ altar in the friary church at Meelick. In July of 1784 two of the friars recorded their having sold ‘the burial place which heretofore belonged to John Horan’s family now extinct to Mr. James Dillon and family.’ As payment for the sale of the Horan burial place the friars received ‘a barrel of wheat, cost £1.15s and five shillings worth of potatoes.’[xli] The burial site they described as lying ‘from the Gospel side of the great altar to the chapel door.’

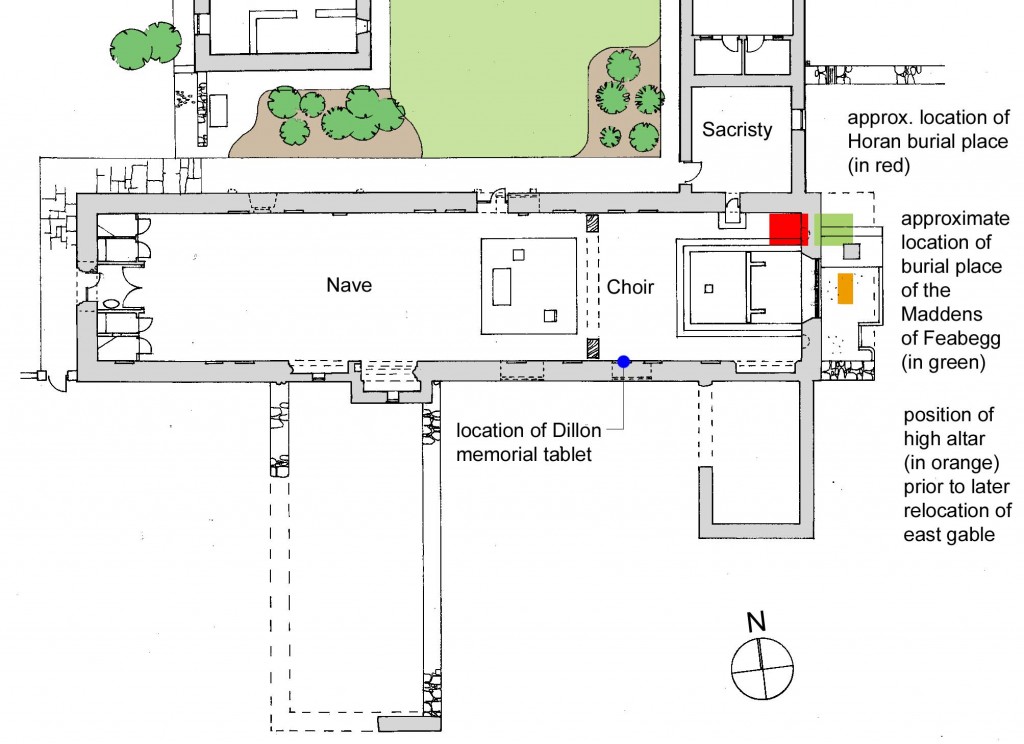

It is noteworthy that, while the memorial tablet erected by Penelope Dillon alias Horan was set into the south wall of the church choir at Meelick, the burial place of the Horans would appear to have lain between the altar and the north wall of the choir. In the eighteenth century the friary church proper would appear to have been in a ruinous condition and the contemporary friars made reference to the ‘chapel’ as formerly the ‘sacristy of our old church’ (‘nostro sacello seu olim nostrae ecclesiae sacristia’).[xlii] This would imply that the Horan burial place lay between the altar and the door to the former sacristy, on the opposite side of the choir to that wall whereon the Dillon memorial was erected.

Plan of Meelick Roman Catholic church reflecting its configuration in the late twentieth century and the approximate location of the Horan burial place. As the east gable was rebuilt in the nineteenth century approximately 3 metres to the west of its original position and the seventeenth century burial place of the Maddens of Feabegg, great-grandsons of the last Gaelic chieftain of Síl Anmchadha, was located to the left of the high altar, it would suggest that the Horan burial place, shown in red, was located about the head of the Madden burial place in the church.

[i] Knox, H.T., The Early Tribes of Connaught: part 1, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth series, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1900, p. 349; Mannion, J., The Senchineoil and the Sogain: Differentiating between the Pre-Celtic and early Celtic Tribes of Central East Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 58, 2006, pp. 166, 168; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Leabhar na g-ceart or The Book of Rights, Dublin, M.H. Gill, for the Celtic Society, 1847, p. 106.

[ii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 24-59.

[iii] Egan, P.K. and Costello, M.A., Obligationes pro Annatis Diocesis Clonfertensis, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 21, 1958, p. 61, footnote 37.

[iv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 86-7.

[v] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 4-5.

[vi] K.W. Nicholls, The Episcopal Rentals of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, IMC, 1970, p. 136.

[vii] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 8: 1427-1447, London, 1909,Lateran Regesta 330: 1435-6, p. 542.

[viii] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 12: 1458-1471, London, 1933,Lateran Regesta 545: 1459, pp. 35-40.

[ix] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 44, 67-8.

[x] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p. 426, Sir Edward Fitton to the Lord Deputy, Galway, dated 22nd February 1570. Both Meelick and Fahy were also administered by one parish priest in the early eighteenth century and this appears to have been the case up to the early nineteenth century.

[xi] Fiants Eliz. I

[xii] Fiants Eliz. I

[xiii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 87-8. This townland was described as the 2 quarters of Carrowcloghy Tullaghanelicky als Ballyeghnagh circa 1641. Also Cal. Pat. Rolls 16 Jas. I, p.414

[xiv] W. Wilson, The Post-chaise companion; or travellers directory through Ireland (4th edition), Dublin, J. Fleming, No. 6 Dame Street, 1786, p. 569.

[xv] The Hamilton residence at Greenfield, located on the right hand side of the road as one travelled from Eyrecourt to Portumna about 1786 is a different residence from that house known as Greenfield House, located in the same townland of Fahy but on the left hand side of the public road. The latter house was not constructed until the nineteenth century as evidenced by its appearance only on later Ordnance Survey maps.

[xvi] O Donovan, J., Ordnance Survey Letters, 1838, County Galway, p. 175.

[xvii] Local folklore in this case refers to accounts of a stone or stone slab of note on a height once located there.

[xviii] N.L.I., Dublin, G.O., Ms. 146, Linea Antiqua (Betham), p. 272, 298, 299. Fenola, daughter of Connor O Horan of Fahy married John Madden of Derryhiveny, who died in 1639.

[xix] Cal. Inquisitions (Chancery), Co. Galway, Eliz. I -William III.

[xx] Rory is given elsewhere as Rory mcConor mcDermot O Horan of Fahy.

[xxi]John was described as of Ballynakill in an inquisition of 1633 relating to the property of Hugh O Madden of Newtown in Lusmagh parish, deceased. John mcRory mcConnor O Horan held one quarter and a fifth of a quarter in Ballynakill in 1641. (Books of Survey and Distribution)

[xxii] Cal. Pat. 16 James I

[xxiii] NLI Dublin, G.O., Ms. 221, Milesians II, p. 167.

[xxiv] Calendar of the Patent & Close Rolls of Chancery in Ireland, Chas. I, Dublin, 1863, Vol. I.

[xxv] Obituary of the Abbey of Meelick; Fennessy, I., OFM, The Meelick Obituary and Chronicle (1623-1873), Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 60, p. 369.

[xxvi] Simington, The Transplantation to Connacht.

[xxvii] The Irish Genealogist, Vol. 4, p. 275.

[xxviii] The Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, Co. Galway, I.M.C. 1962

[xxix] Gantz, I., Signpost to Eyrecourt, Kingsmead, 1975, pp. 128-130.

[xxx] Mulloy, S., Galway in the Jacobite War, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 40, 1985-6, pp. 3-4; Blake-Forster, C.F., The Irish Chieftains or a Struggle for the Crown, Dublin, McGlashan and Gill, 1872, pp. 636-7.

[xxxi] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. xix.

[xxxii] Simms, J.G., Irish Jacobites, Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, 1960, pp. 14-5.

[xxxiii] Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, Dublin, 1960, p. 14, p. 72.

[xxxiv] Analecta Hibernica No. 22, I.M.C. Dublin, 1960, p.113.

[xxxv] I. Par. Returns, Y.6,B.73, unnumbered

[xxxvi] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. No. 170, Registered Pedigrees Vol. 16, c. 1816-1817, pp. 271-299; Fennessy, I., OFM, The Meelick Obituary and Chronicle (1623-1873), Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 60, pp. 345, 358, 369, 391.

[xxxvii] NLI, Dublin, G.O. Ms. No. 170, Registered Pedigrees Vol. 16, c. 1816-1817, pp. 271-299; Fennessy, I., OFM, The Meelick Obituary and Chronicle (1623-1873), Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 60, pp. 345, 358, 369, 391.

[xxxviii] Land Registry, Vol. 173, p. 1, No. 114881 (1728 and later deed of 1754), Land Registry, Vol. 35, p. 25, No. 17352 (1720).

[xxxix] Registry of Deeds, Vol. 91, p. 455, Memorial No. 64850; Vol. 92, p. 500, Memorial No. 65412.

[xl] Fennessy, I., OFM, The Meelick Obituary and Chronicle (1623-1873), Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 60, p. 369.

[xli] Fennessy, I., OFM, The Meelick Obituary and Chronicle (1623-1873), Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 60, p. 417.

[xlii] Fennessy, I., OFM, The Meelick Obituary and Chronicle (1623-1873), Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 60, p. 331, footnote 25, p. 385.