© Donal G. Burke 2013

The Lallys or O Mullallys of east Galway are an offshoot of the wider Uí Maine family group, whose ancestor has traditionally been held to be Maine mór, son of Eochaidh feardaghiall, chief of a tribe of people who established themselves as the dominant group in the south-eastern region of Connacht by about the end of the fifth century.[i]

Maine mór and his descendants appear to have subjugated many of the existing tribes and peoples that inhabited their land and established a petty kingdom, covering much of the later east Galway named from their progenitor as Uí Maine (later Anglicised Hy Many).

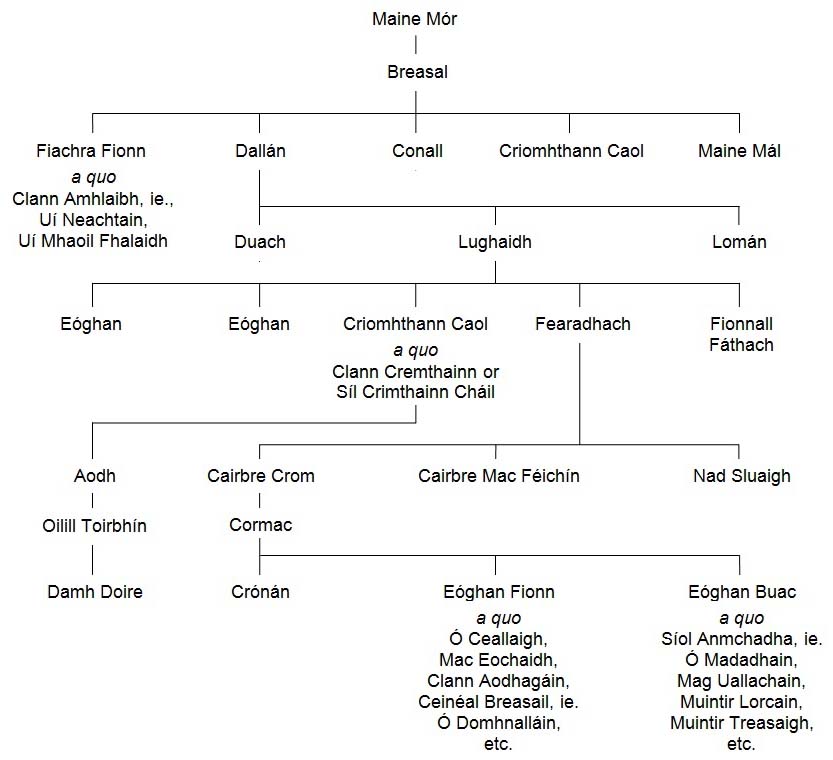

The line of the O Mullallys, or as the name was written in older Irish, Ó Maeilalaigh or Ó Maelfhalaigh, descend from the eldest of five grandsons of Maine mór; one Fiachra fionn, son of Breasal. As such they were initially closely related to the O Naughtons, who were descended from a more senior descendant of the same Fiachra fionn.[ii] Despite their seniority in line of descent, the Lallys and the O Naughtons would be superseded by the O Kellys, a family of more junior descent from Maine mór, descended from the second eldest grandson of Maine mór; Dallán son of Breasal.[iii] From the O Kellys would be drawn the kings or chieftains of the wider territory of Uí Maine.

Pedigree derived from MacFirbisigh’s seventeenth century ‘Great Book of Irish Genealogies, showing the relationship between the Lallys (ie. Ui Mhaoil Fhalaigh or Ó Maelfhalaigh), the Naughtons, the O Kellys, O Maddens and various other senior families descended from Maine mór.

The Book of Lecan, a Gaelic manuscript compiled in the early fifteenth century, gave the family name as deriving from Maelfhalaigh, son of Cucichi, son of Maeltuili son of Maclaeich son of Connalach, son of Amhalgaidh, son of Deinmnedhach son of Dima son of Laidginn son of Maeluidhir son of Aedh son of Finntan son of Amhlaibh son of Fiachra finn, grandson of Maine mór. The descent of Maelfhalaigh is given differently by the antiquary Dubhaltach MacFirbisigh in his seventeenth century ‘Great Book of Irish Genealogies.’ Therein the descent of the Uí Mhaoil Fhalaidh or Uí Mhaelfhalaigh is said to converge with that of Ó Neachtain in the person of Fearghus son of Oilill son of Tuathghal son of Mac Laoich son of Condálach son of Amhalghaidh son of Fiachra Fionn son of Breasal son of Maine Mór.[iv] In Dubhaltach MacFirbisigh’s work this Fearghus, common ancestor of both the Uí Neachtain and the Uí Mhaoil Fhalaidh, is grandfather of that Neachtain from whom the Uí Neachtain derive their name. The Book of Lecan also gives the son of Fiachra Fionn as Amhlaibh and refers to Ó Neachtain as of the Clann Amhlaibh, (ie. ‘the family of Amhlaibh) whereas MacFirbisigh gives the same son of Fiachra Fionn as Amhalghaidh.

Dubhaltach macFirbisigh’s account of the descent of Ó Neachtain or O Naughton, despite being at variance with the Book of Lecan, agrees with those given by Peregrine O Clery in his genealogies and with O Farrell in his ‘Linea Antiqua.’ The nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan, in describing O Naughton in his ‘Tribes and Customs of Hy Many’ as ‘the senior of all the Hy Many,’ although none of that immediate name held the chieftaincy of that territory, thereby took the ancestor of the Uí Mhaoil Fhalaidh or O Mullallys as junior to that of the Uí Neachtain or O Naughtons.

In the Book of Lecan the foremost early line from Maelfhalaigh was given as coming down through his son Domhnall who was father of Ceinneididh father of Domhnall father of Gilla Christ the father of Amlaidh.[v]

The O Mullallys and the O Naughtons ruled at different times within the early territory of Uí Maine, known as Moenmoy.[vi] The Rev. P.K. Egan described the territory of Moenmoy or Maonmagh as an area situated about Loughrea and having bordered the O Madden territory of Síl Anmchadha to the east about Finnure and Cormick (‘Uí Cormaic’).[vii] On its western boundary it bordered the territory of Uí Fiachrach Aidhne about Seefin and its north-western Moyode. On its northern boundary it extended to include at least parts of the parishes of Kiltullagh, Killimordaly and Grange, extending up towards the territory of the Soghain in the later barony of Tiaquin in the north-east of what would later be County Galway. To its south it was believed to have extended to the Cinel Fheichin, the later civil parish of Ballinakill.

The Anglo-Norman conquest of Connacht

John O Donovan was of the view that both the O Mullallys and the O Naughtons may have been deprived of their control of Moenmoy in the time of Conchobar maenmhaighe O Conchobhair or O Connor, who died in 1189.[viii] Following the conquest of Connacht by the Anglo-Norman Richard de Burgh and his supporters in 1235, de Burgh established his principal castle at Loughrea and, while he granted certain territories or cantreds within Connacht to his Anglo-Norman followers, he retained direct control over the cantred of Moenmoy.

The O Mullallys and the O Naughtons are found thereafter further to the north and east. The O Naughtons would be located in a heavily wooded area known as the Ffaes close to the new Anglo-Norman castle at Athlone, about the five cantreds of Connacht reserved to the English King. The southern-most of these five cantreds was Omany, (Uí Maine) wherein was confined for the most part the remaining ancestral lands of the O Kellys and their associated families. The O Mullallys, for their part, were thereafter based in the barony of Dunmore, about the parish of Tuam, immediately north of the town of Tuam.[ix]

Following the allocation of lands by the Anglo-Normans the area to which the O Mullallys relocated was in the possession of the de Berminghams, de Burgh’s chief tenants in Connacht.[x] The O Mullallys were significantly reduced from the position they formerly held in Moenmoy and in the barony of Dunmore the head of the name held only a small area of land as tenants of de Bermingham and his heirs. [xi]

Ecclesiastics

Like many of the families of Gaelic and Anglo-Norman origin of the territory, the O Mullallys, down the centuries, provided ecclesiasts to the Archdiocese of Tuam, the diocese of Clonfert and surrounding dioceses.

Isaac O Mullally was a canon of Clonfert in 1414 when assigned the task, together with the abbot of Knockmoy in Tuam, of taking the prebendary of Kilmeayn in Tuam from two clerics of the diocese of Clonfert who had detained it illegally and assign it to a clerk of Tuam.[xii]

Isaac O Mullally held the perpetual vicarage of Killcouane in Clonfert Diocese in the early fifteenth century although he was never ordained a priest. Another of the family, one Dermot O Mullally, also appears to have been associated with the same vicarage about that time as the Papal authorities ordered in 1427 or 1428 that, given that Isaac was dead by that time and irrespective of the resignation of Dermot, the vicarage was to be granted to Bernard O Kelly, an Augustinian canon of St. Catherine’s at Eachdruymomane (Aughrim Uí Maine).[xiii]

The Franciscan Cornelius or Connor O Mullally was appointed Bishop of Clonfert in 1447 and in 1448 was translated to the diocese of Emly, and thereafter translated to the diocese of Elphin in 1449, dying in 1468 as Bishop of Elphin.

Thomas O Mullally served as Bishop of Clonmacnoise from about 1509 to 1514 and was then appointed Archbishop of Tuam, dying in that office in April of 1536. He was said to have been a particular benefactor of the Franciscan Order and had an altar erected at their friary at Kilconnell bearing the inscription in letters of gold ‘Lord Thomas O Mulally, Archbishop of Tuam, an extraordinary benefactor of our Order.’[xiv] His effigy and name were also said to have been located on an altar in the choir of the Franciscan friary of Rosserrilly, near Headford in County Galway.[xv] He was buried at the Franciscan friary at the town of Galway in the tomb of his predecessor. Although a cleric he had a son William, who was his eldest son and heir and who would later be appointed by the Queen of England as the Protestant Archbishop of Tuam.[xvi]

At the time of the Visitation of the Diocese of Clonfert in the late 1560s by the Bishop, Roland Burke, the vicarages of ‘Foynach and Kyllyncoste’, related to the rectory of Aughrim, were held by one Edmundus O Mulali.[xvii] The vicarage of ‘Foynach’ would appear to be that of Fohenagh, about which a number of Lallys also held land.

Hawkins Ulster pedigree of Mullally

A pedigree of the family of O Mullally was compiled about 1777 for a French descendant of the family by William Hawkins, Ulster King of Arms. Much of the early details of this was regarded by the antiquary John O Donovan as incorrect or a fabrication.[xviii] O Donovan, however, was of the view that the details of certain material relating to members of that family of the early modern period was correct.

This pedigree gave the head of the family at the end of the sixteenth century as Dermot O Mullally of Tullynadaly, son of John son of Melaghlin son of Dermot O Mullally. The pedigree, while giving the death of Dermot son of John as having occurred in 1596 and his wife as Mary, daughter of William O Naghten of Lisnea, County Roscommon, erroneously states that he bore the title of ‘2nd Baron of Tully-Mullally,’ which was an inflated exaggeration of his status. The pedigree gives his son as Isaac O Mullally or Lally of ‘Tullen Adalla’ and again incorrectly attributed to him the title of baron.

The senior line of the O Mulallys about this time, however, was more correctly that of Thomas O Mulally, who was appointed Bishop of Clonmacnoise by Pope Julius II in 1508 and was elevated to the Archbishopric of Tuam about 1513 or 1514. A funeral entry in the records of the Ulster King of Arms state that he was succeeded by his eldest son and heir William O Mulally. [xix] This William pursued a career in the Protestant Church and was appointed by Queen Elizabeth I as Protestant Archbishop of Tuam about 1572. He was, in turn, succeeded to the ancestral property about the parish of Tuam by his eldest son and heir, Isaac O Mulally of Tullaghdaly.[xx] It would appear likely that the pedigree prepared by Hawkins manipulated the facts to conceal the descent from a Protestant clergyman of the later French members of the family.

Proprietors of land in early seventeenth century

The O Lallys held lands about both the parish of Tuam in the barony of Dunmore and about the barony of Kilconnell in the late sixteenth century. Thomas Lally ‘of Ballinecloghy’ was active as a rebel during the Nine Years War and, having been killed in rebellion, his lands were among the many confiscated by the Crown. His lands appear to have been located principally about the parish of Kilconnell and consisted of the quarters of Ballinecloghy, Barnevihane and Killaghibegg (This ‘Barnevihane’ appears to be the modern townland of Barnavihall in the parish of Kilconnell). In March of 1605 the Crown granted his lands to Sir Henry Broncar, President of Munster, as part of vast estates given him after the war.[xxi]

The residence of Isaac Lally, the leading individual of the name, was located at Tullaghdaly in the parish of Tuam in the early seventeenth century. ‘Isacke Lally of Tullanedally’ was among the many persons across the province to whom a general pardon was extended by the Crown in 1603, the first year of the reign of King James I.[xxii] Also pardoned in that year was William oge O Mullally of Tullandally and one Nicholas O Mullally of the Clogher, gentleman.[xxiii]

Hawkins pedigree of the family gives Mary, daughter of John More of Brieze, County Mayo and Cloghan Castle in Lusmagh (then in County Galway) as the wife of Isaac of Tullaghdaly but it is clear from his funeral entry in the records of the Ulster King of Arms that he was married to Mary or Marrun, daughter of Nehemias Donnellan, Protestant Archbishop of Tuam.

The lands of Isaac in 1618 lay in the immediate vicinity of the town of Tuam in the barony of Dunmore. In that year Isaac Lally ‘of Tullaghnedallie, gentleman’ was confirmed in possession of the castle, town and lands of Tullenedally, the quarter of Carrowcaslane, the quarter of Gortneponry, an eighth part of the four quarters of Lisbally, half of the quarter of Drum, five eights of the quarter of Tominame and half of the quarters of Carrownemonine and Carrownegarrane.[xxiv] From each quarter of land he paid a yearly rent to Lord Bermingham.[xxv]

At that same time William Lally ‘of Ballybannibby, gentleman’ held lands in the vicinity of those of Isaac in the barony of Dunmore consisting of half of the quarter of Carrownelahie, an eighth part of ‘Lisvally’ and a fourth part of Curine, rented from Lord Bermingham.[xxvi] In addition to those lands he held lands further to the south-east, about the parish of Fohenagh in the barony of Kilconnell, where he resided. There he held the castle, town and lands of ‘Ballynebanby’ (the modern townland of Ballynabanaba, parish of Fohenagh) in close proximity to the lands of the O Dugans, a cartron of Gortfoill and lands in Lisumolly, Gorteglagly and Cloonenanowill.[xxvii]

Daniel Lally appears to have resided near Tullaghdaly, being described about 1618 as ‘of Lisbally, gentleman.’ (Within the modern townland of Lissavally Vesey in the parish of Tuam, immediately south of the site of the castle of Tullaghdaly lay a large ringfort known as Lissabally from which this townland derived its name. The lands of Daniel of Lisbally all lay within the barony of Dunmore and consisted of the quarter of Rathnamanry, half of the quarter of Carrownelahie (the other half of which was held by William of Ballynabanaba) and one eighth part of Lisbally.[xxviii] He again also paid an annual rent to Lord Bermingham.[xxix]

Other junior Lallys also held lands in the barony of Kilconnell at that time, with Donough McConnell (ie. ‘son of Connell’) O Lally of Kilconnell holding the quarter of Cormenan and Donell Lally of Ballymote and Honor, his wife, together with one O Kelly of Cloncoyle and his wife holding lands at Coilnepory, Carrowmoe and Knockroe.[xxx]

The funeral entry in the records of the Ulster King of Arms for ‘Isaack O Mullolly of Tulloghdaly’ gave his death as having occurred on the 16th July 1631.[xxxi] The Hawkins pedigree erroneously gives this date as May 1621 but correctly gives James O Mullally or Lally as his son and heir.[xxxii] Isaac died at ‘Ballymott’ and was buried at the Cathedral Church of Tuam. Details of his parentage, marriage and offspring were provided to the Ulster King of Arms seven years later by his third son Isaack, who described his father as ‘descended from Maylfalla O Kelly, second son of O Kelly of Atherin’ and having had seven sons and three daughters by his wife Marrun Donolan; James, William, Isaack, Richard, Richard, Edmond, Francis, Sisly, Margarett and Mary. At the time the younger Isaack provided Ulster with the details in 1638 Richard was married to Elizabeth Dillon while both William and Isaack were unmarried. The first-mentioned Richard had died young without issue and the second, together with Edmond and Francis were all young and unmarried. Sisly, the eldest daughter and Mary, the youngest, had also died young while Margarett was married to one William Garvey of County Galway.

Mid Seventeenth Century, prior to the Cromwellian period

This James O Mullally or Lally, according to Hawkin’s pedigree, was married in 1623 to Elizabeth, daughter of Gerald Dillon of Freymore, County Mayo, brother of Theobald, 1st Viscount Dillon. (His father’s Funeral Entry gave James as married to Elizabeth, daughter of Richard Dillon.)[xxxiii] In the late 1630s he was the principal landholder of the name, the proprietor of the quarters of Carrowcaslane and Lisuale and, alongside others such as Lord Bermingham, proprietor of part of Carranarough, Carrogarrin and Carrowmonin, all in the parish of Tuam.[xxxiv] The castle of Tullinadaly stood in the modern townland of Castletown, which would appear to be that Carrowcaslane (ie. ‘ceathrú an caisleain’, ‘the quarter of the castle’) referred to as held by James Lally. At that same time Donell Lally held the quarters of Ranamary and Caronalaghy in the parish of Tuam.[xxxv]

Also in the late 1630s William Lally held the quarter of Ballinabannaba and a half quarter of Ballydoogane along with a parcel called Gortegolloglye, (ie., ‘the field of the Galloglass or mercenary’) the latter when taken together making one quarter, all in the parish of Fohenagh. [xxxvi]

The Hawkin’s pedigree gave both Donell and William as brothers of James of Tullinadaly.[xxxvii] It is unclear if William of Ballinabannaba was the third son of Isaac of Tullaghdaly but the pedigree is incorrect in relation to Donell as Isaac had no son of that name and as he appears to be given elsewhere in the late 1630s as ‘Donell McWilliam McThomas O Lally,’ it is likely that he was a younger brother of Isaac. [xxxviii]

The pedigree states that William of Ballynabanaba married Frances Butler, by whom he had a son Edmund Lally, married to Eliza Brabazon. This would appear to be the same Captain Edmund Lally who, about the year 1700, claimed the remainder of a 31 year lease that had commenced on the 1st May 1678 on lands at Carrowgary and elsewhere in Count Roscommon, formerly the property of Hugh Kelly.[xxxix]

The Cromwellian period

The Lallys lost possession of their lands in this area as a result of the Cromwellian confiscations and transplantations in the mid seventeenth century. Following the turmoil of that period and the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, an Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time.

The Hawkins pedigree stated that James Lally of Tullinadaly, son of Isaac, forfeited part of his estate under the Cromwellian authorities in the mid seventeenth century, but although the ownership of the property at Tullinadaly appears to have changed hands, Lally remained at Tullinadally until his death.[xl] According to the Hawkins pedigree both Donell and William Lally were said to have been outlawed for their support of the monarchy and their estates declared forfeit.[xli] However, James Lally of Tullynedally was allocated 582 profitable Irish acres within the parish of Tuam and Daniel ‘of Curraghreahy’ was allocated 18 profitable Irish acres.[xlii] Under the Act of Settlement the ownership of the lands of James, Donell and William Lally were confirmed in the possession of others.[xliii]

James Lally was said by the pedigree to have died at Tullaghdaly on the 5th September 1676.[xliv] He was survived by his eldest son and heir Thomas Lally, who inherited his father’s real estate.

While the Hawkins pedigree states that the will of James Lally was not tested until 7th June 1677, it would appear from legal claims made about 1700, relating to bequests of a will dated on that same day, it would appear that the will in question may have been that of Thomas, who may have died not long after succeeding as heir.

Thomas Lally, son of James, married Jane Dillon, sister of Theobald 7th Viscount Dillon of Costello Gallen.[xlv] On her marriage to Thomas lands comprising two quarters of ‘Ballimote’ in the barony of Dunmore were settled on Jane.[xlvi]

Children of Thomas Lally and Jane Dillon

Thomas Lally and his wife Jane had five sons and four daughters; James, Gerard, William, Mark and Michael. Of his daughters, Mary, the eldest girl, was married to Walter Jourdan, the second to Nicholas Nangle, the third to one N. O Gara and the fourth to N. Betagh.[xlvii]

In his will Thomas left his real estate to his eldest son James Lally and to his male heirs born in matrimony and for want of such heirs the estate was to pass to Gerard Lally, second son of Thomas.[xlviii] Despite the families association with the Protestant religion, James and his brothers adhered to the cause of the Roman Catholic King James II during the Jacobite-Williamite War in Ireland.

In the year 1687 the pedigree states that James was appointed ‘governor and sovereign of the noble corporation of Tuam’ and in 1687 served as a Member of King James’ Parliament of 1689. Many of the principal Roman Catholic landholders of county Galway served as officers in the Jacobite army and at the outbreak of the war in Ireland between the supporters of King James II and the Protestant William of Orange James Lally held a commission as a captain in the infantry regiment of his kinsman Colonel Henry Dillon, while his brother Gerard served as Lieutenant in the same company.[xlix] In the infantry regiment of Ulick Burke, Colonel Lord Galway, younger brother of the Earl of Clanricarde, Edmund Lally held the rank of captain, while in that same company one James Lally served as an ensign.[l] Both James and Gerard were posted early in the war to France as Dillon’s regiment was transferred there alongside four other new Irish regiments in 1689 in exchange for six French regiments sent to Ireland to support the Irish forces raised in support of King James II.[li] James Lally was commanding a battalion in Dillon’s Irish regiment in 1690 but was killed in 1691 during the blockade and siege of Montmelian.[lii]

For their support of the Roman Catholic king, James and Gerard, both described as ‘of Tullendally,’ were among those Jacobites outlawed by the Williamites for treason ‘beyond the seas.’[liii] James was attainted and his property declared forfeit.[liv] As James was unmarried at his death, the line of Gerard, second son of Thomas Lally and Jane Dillon became the senior line of the family.

Most of James Lally’s brothers found service with the army of the Catholic King of France, with Gerard attaining high rank therein. The Hawkins pedigree states that their brother William also served as a captain in Dillon’s regiment and was killed in 1697, while Mark also served as an officer in the same regiment. While all five were said to have left Ireland to serve in the French army, Michael, the youngest, was resident in County Galway in 1714. His son Michael, by his wife Helen O Carroll was born at ‘Ballyveck, Tuam’ on the 1st July of that year.[lv] This son would later leave Ireland to serve in his kinsman’s regiment in France.

The forfeited estate of James Lally circa 1700

In Ireland, where the estate of James Lally had been declared forfeit, a number of the family made claims about the year 1700 before the Trustees for the Sale of Forfeited Estates in Ireland. Their mother, Jane Dillon, widow of Thomas Lally, had married after the death of Thomas one John Burke and he and Jane claimed the lands of ‘Ballimote’ and other lands as her dower before the Trustees. Jane Burke was adjudged by the Trustees to her dowers on the lands of Tullinaday and elsewhere.[lvi]

Among others of the family with claims before the Trustees at this time was Michael Lally, who claimed a legacy of 20l. by will dated the 7th June 1677, of lands of one quarter at Niard and one quarter at Drum and several other lands, all in the barony of Dunmore in County Galway, the late proprietor having been James Lally. This would appear to have been the youngest brother of the attainted James.[lvii]

Bridget Lally claimed a portion of 100l. from the same will out of the same lands associated with Michael’s claim, and Walter Jordan and Mary Jordan alias Lally his wife claimed a 160l. portion by the same will on the same lands. Both Bridget and Mary appear to have been two of the four sisters of James. [lviii]

While James’ brother William was said to have been killed in 1697, one William Lally, gent., had a claim before the Trustees relating to the remaining period of a twenty-one year lease taken out in September 1684 on lands at Ballinsmala and Carane, near Claremorris in County Mayo, the late proprietor of those lands being Gerald Dillon.[lix] As the claims listed before the Trustees were entered with them either on or before August 1700, it may be possible that this was a claim entered by William with the Trustees prior to his death in 1697.

Others claiming an interest in the forfeited estate of James Lally was Henry Viscount Dillon, who claimed a 60l. mortgage on lands at ‘Tumneenone als Bellamore, with the mills and other lands’, all in the barony of Dunmore, by deed of 31st October 1672 to Christopher Dillon from both James Lally and Thomas Lally and a subsequent deed from Thomas only, dated 17th April in the 27th year of King Charles II, apparently after the death of Thomas’ father James. Christopher Dillon assigned the interest to Henry Viscount Dillon in December of 1697, who subsequently presented his claim with the Trustees dealing with the forfeited estate of Thomas’ son James.[lx]

The confiscated Tullinadaly estate of James Lally, including its castle and surrounding lands was sold in 1703 to one Edward Crew of Carrowkeel, County Galway ‘subject to the legacy to Michael Lally and portions to Bridget Lally and to Mary Jordan alias Lally.’[lxi]

Another of the family with claims before the Trustees was Edmund Lally. Edmund Lally, gentleman, on behalf of himself and his wife Frances, in right of his wife, claimed an estate for life of lands at Carrowgary and elsewhere in County Roscommon, by the last will of John Dillon, the last proprietor of those forfeited lands being Gerald Dillon.[lxii] He was, in all likelihood, the same Edmund who claimed, on behalf of William Butler, who was a minor at the time, a mortgage in fee of 101l. plus interest relating to lands at Streamstown and other lands in the barony of Garrycastle in Kings County, the forfeited lands formerly in the possession of one John Coghlan. Lally was described as the ‘next friend’ of the minor, and served as one of the executors of the will of William’s father, Thomas Butler.[lxiii]

This Edmund would appear to be that Captain Edmund Lally of Colonel Lord Galway’s regiment, son of William of Ballynabanaba mentioned in the Hawkins pedigree, but his wife is given circa 1700 as Frances, as opposed to Eliza Brabazon. The pedigree stated that Edmund was son of William Lally and Frances Butler, which supports his identification as the same man, but, either Edmund was married twice or Edmund’s wife was Frances was Frances Butler. Given his landed interests in County Roscommon and rank he would appear to be the same individual as Captain Edward Lally of Dromolgagh, County Roscommon, whose claim to be included among those Jacobites who would benefit from the articles of the Treaty of Limerick at the end of the war were heard by the Irish Privy Council in November 1694.[lxiv]

Sir Gerard Lally, bart. and the senior line of France

The senior line of the family, after the death in 1691 without legitimate issue of James, was that of his brother Gerard. After the surrender of the Jacobite forces in Ireland at Limerick in 1691 Gerard sailed for France and rose to hold the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in Dillon’s Irish regiment, commanded by his cousin General Dillon. In April of 1701 he was stationed with the army at Romans-sur-Isère, in the French diocese of Vienne and there, at the age of about thirty-five years, on the 18th of that month, married Anne Marie, daughter of Charles Jacques de Bressac, Seigneur de la Vache.[lxv] by whom he had one surviving son, Thomas Arthur Lally.[lxvi] Their only surviving son was born at Romans, in Dauphiné, on the 13th January 1702 and baptized two days later.[lxvii]

For his services to the Stuart claimant to the throne in exile, known to the Jacobites as King James III, that King in exile created Gerard Lally a baronet by letters patent dated July 1707 at St. Germains-en-Laye.[lxviii] He was appointed Brigadier-General in the army of France in 1734 ‘with the promise of being made at the next promotion a Marèchal-de-camp.’[lxix] He died at Arras in November of 1737, before he was made Marèchal-de-camp. His baronetcy entitled him to the style of Sir Gerald Lally, bart., as he was identified in the Hawkins pedigree, but as this was created by the Stuart claimant in exile it was not recognised by the then monarchy of England.

Thomas Arthur, 1st Comte de Lally-Tolendal

Sir Thomas Arthur Lally, second baronet, only surviving son and heir of Sir Gerald, 1st bart., succeeded his father at about the age of thirty-five years. From an early age he had been reared in the military tradition and received a commission in the Dillon regiment on the 1st January 1707 at the age of about five years. He was present at the battles of Gerona in 1709 and at Barcelona in 1714 at the ages of seven and twelve years. He attained the rank of Captain in Dillon’s regiment in 1714 and as he rose through the ranks won recognition for his military knowledge. [lxx]

It was said of him that ‘his father’s experience gave him knowledge of his profession, whilst his mother’s relationship with some of the most illustrious families in France caused his introduction to the higher circles of society and imparted to his manners that tome and polish so characteristic of the old French aristocracy.’[lxxi] It was likewise said by the same author that ‘amongst other lessons impressed upon the mind of Lally at this early and impressive period in his life was a bitter and unrelenting hatred of the English – or rather of the family which then sat on the throne of England.’ A committed Jacobite, his reputed antipathy to the English was attributed to his father’s influence, who ‘taught him to consider the humiliation of the House of Hanover as the one great end and object of his life.’[lxxii]

Thomas Arthur found favour with the Regent of France, who sought to have the eighteen years old Lally appointed a colonel, but Lally’s father spoke against the proposal, wishing his son to advance through the ranks on his own merit.[lxxiii]

Both father and son were active in the War of the Polish Succession, with the son achieving notice for his bravery and military ability at the siege of Kehl. Both were present at the battle of Etlingen in 1734 in which Sir Gerald Lally was seriously wounded. The father was said to have been about to be captured by the enemy ‘when his son threw himself between them and his father, covered him with his own body and, by prodigies of valour, succeeded in rescuing him.’[lxxiv]

Thomas Arthur continued the family support for the Stuart cause and in 1737, about the time of his father’s death, he undertook a reconnaissance mission to determine suitable landing places in England ‘for landing an army and establishing communications with the different Jacobite centres.’

During a lull in the wars between the principal European powers Lally undertook a mission to Russia, initially on his own initiative with the intention of interesting the Czarina in his projects against England but later, with official sanction from the French minister, to attempt to put in place a coalition between France and the Northern Powers against England. This mission proved unsuccessful in part due to the French Minister’s refusal to provide instructions to Lally while he was in St. Petersburg.[lxxv]

He fought in Flanders in 1744 at the sieges of Menin, Ypres and Furnes and in October of that year was appointed Colonel of a newly formed Irish infantry regiment to be known from their commander as Lally’s Regiment.[lxxvi] Under Lally the regiment was present at the siege of Tournai and played a decisive role in the defeat of the British forces at the battle of Fontenoy on the 30th April 1745. For his part in Fontenoy he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier des armées by King Louis XV on the battlefield.[lxxvii]

Lally served as Quartermaster-General of the Jacobite expedition that sailed to Scotland in 1745 under Prince Charles Edward Stuart or ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ in an attempt to restore the Stuart Royal Family to the throne. Lally joined the young Prince on that expedition and served as his Aide-de-Camp at the battle of Falkirk in January 1746. After Falkirk Lally made his way to Ireland and from there to Spain in the hope of gaining assistance for the Stuart cause. He also went covertly to England at that time but was discovered and ordered to leave the country. He returned, however, to London, whereupon a reward was offered for his taking. He escaped, disguised as a sailor but was taken by a boat of smugglers. He dissuaded his captors from turning him over to the English by suggesting that his knowledge of France to ply their trade off the French coast. The smuggler’s boat was thereafter captured by a French naval vessel and brought to Boulogne where the governor released Lally. He then made his way to the court of the French King to seek further aid for the Stuart cause in Scotland but before military aid could arrive the Jacobite Scots were defeated at Culloden and the Rising failed.[lxxviii]

On his return to France the Old Pretender, known to the Jacobites as King James III, created Lally Earl of Moenmoyne, Viscount Ballymole and Baron of Tollendally.[lxxix] The title acknowledged the various territories with which the family had been associated in County Galway, but, like his baronetcy, as a Jacobite title was not recognised by the established Royal House of Hanover who at that time ruled Great Britain. He re-joined the regular French army, achieving note at the battle of Lafelt and the siege of Berg op Zoom.[lxxx] He was severely wounded at the siege of Maastrict, but on the securing of peace he thereafter made another covert trip to London in the service of the Stuarts, securing an interview with the Prince of Wales before he was again forced to leave that country.[lxxxi] He continued to rise in the ranks, being appointed Major General on the last day of 1755.[lxxxii]

King Louis XV of France, sometime about 1755, is believed to have either created Lally Count de Lally and Baron de Tollendal in the French Peerage or recognised his Stuart title as official.[lxxxiii] In the following year he was appointed Lieutenant General of the French forces in the French East Indies and among other positions, Commander in Chief ‘of all the French establishments in the East Indies.’ The French Minister of War eventually reluctantly agreed to the appointment, considering of Lally that ‘his stern and unbending character, made still more stern by a long course of prosperity, was not exactly suited to encounter such a state of affairs as were believed to exist in Pondichery.’[lxxxiv] He had some initial military success against the British forces and at the height of his career he was created a Knight Commander of the Order of St. Louis in 1757, and promoted to Knight Grand Cross of the prestigious French Order of knighthood on the 15th January 1761.

He proved unpopular among many of the French in positions of power in India in his uncompromising attempts to reform abuses there. [lxxxv] On the 16th January 1761, after a prolonged siege, he surrendered Pondicherry and was taken prisoner.[lxxxvi] During the assault on Pondicherry, his unpopularity was such that one English officer present at the assault remarked that ‘it is a convincing proof of his abilities the managing so long and vigorous a defence in a place where he was held in universal detestation.’[lxxxvii]

Fall from grace

The loss of Pondicherry had a devastating effect on the French position in India and globally and several of those in power sought to appease public disapproval by falsely accusing Lally of treachery. He was charged with treason, incompetence and among other charges, ‘correspondence with the English and tyrannical administration.’[lxxxviii] Following his capture in India Lally was sent as a prisoner to England. There he learned of the charges and confident of his being able to vindicate himself and defend his reputation, he secured his release on parole in October of 1761 to facilitate his return to France to contest the charges. On his return he was arrested and imprisoned in the Bastille about a month later. Proceedings against him commenced in 1763 and were transferred to the Parliament of Paris in January 1764. [lxxxix] Refused an attorney to defend his case, his trial would last for more than two and a half years.[xc] He remained a prisoner until his trial in May of 1766, at which he was condemned on the 6th May of that year.[xci] He was not informed of his sentence until noon on the 9th May, when he was made to kneel before the clerk of court and hear the verdict.[xcii] He was deprived of his property, all titles, honours and dignities and condemned to be be-headed.[xciii] On hearing the verdict he attempted to kill himself with a compass but failed.[xciv]

Having been initially informed that his execution would be carried out at night, without a baying crowd and that he would be brought to the place of execution with some dignity in a carriage, followed by a hearse, the execution was brought forward six hours. Only at the last moment was he made aware that he would be brought to the scaffold in a dung-cart through a hostile crowd in the manner of a common criminal and gagged to prevent him addressing the crowd and asserting his innocence.[xcv] In addition, his jailers and the executioner’s assistants stole his remaining items of personal property.[xcvi]

Upon the scaffold at the Place de Grève, Lally’s request of the executioner that his hands be untied was refused. He was blindfolded and his gag removed but it was reputed that Lally had not finished his prayers when the executioner struck his blow. The young executioner poorly performed the execution. Rather than one clean stroke, the blade was said to have caught in Lally’s hair and did not kill Lally instantaneously but ‘only opened a great gaping wound.’ The blow was struck, however, with such force that Lally was thrown down upon the platform. The executioner’s father, experienced in that profession, took the weapon from his son and was said to have struck a second blow that then killed Lally.[xcvii] Other accounts, however, claimed that he was only finally killed after five or six blows of a sabre.

His body and head were then unceremoniously thrown into ‘a common hackney’ and taken to the Churchyard nearest the place of execution and buried in the chapel of the Blessed Virgin in church of Saint Jean de Grève.[xcviii]

Trophime Gerard, 1st Marquis and 2nd Comte de Lally-Tolendal

The executed Thomas Arthur Lally had no legitimate son but did have an illegitimate son by one Félecité, daughter of John Crofton of Longford.[xcix] Their son was born in Paris in early March 1751 and named Trophime Gerard. He was reared without any knowledge regarding the identity of his father and educated at the Jesuit College d’Harcourt.[c]

He was fifteen years old when, on the day following Lally’s execution, the dead man’s cousin, the Countess Mary Dillon, sent an officer of the Irish Brigade to the fifteen year old boy’s school in Paris to inform him of his father’s death.[ci] The youth’s birth was officially legitimised and he was brought to reside with the Countess at her apartment in the Chateau de Saint Germain-en-Laye. Upon her death she bequeathed her possessions to Trophime Gerard. [cii]

A strong supporter of the French monarchy, he found favour with the King and in 1773, on the orders of the monarch, entered the first company of the King’s Musketeers. By 1776 he had risen to the rank of a captain of cavalry and in 1782 was promoted to second captain of the king’s regiment of cuirassiers.[ciii]

Trophime Gerard Lally from an early age sought to have his father’s name cleared. Not long after his death it became accepted in certain quarters that an injustice had been done and a commission of enquiry was established. Foremost among those who knew Trophime Gerard’s father and worked assiduously for his rehabilitation was the French philosopher Voltaire. As a result of this work Thomas Arthur Lally’s name was cleared and the judgement of the Parliament of Paris that found him guilty of treason and other charges was reversed. This sentence of his father was cancelled in May 1778 by the King in Council and his innocence formally declared.[civ]

A capable orator and writer, he was elected to the Estates General as a deputy of the noblesse of Paris in 1789 and was noted for calming the mob of Paris after the fall of the Bastille with a speech from the Hotel de Ville. Disillusioned by the Revolution’s treatment of King Louis XVI he left France for England. He returned in 1792 with the intention to facilitate the King’s escape but was arrested but released and fled to England before the worst excesses of the Revolutionary executions of the aristocracy.[cv] His offer to the French National Convention, tendered from his residence in England, to represent the French King at his trial was ignored by the revolutionary authorities.[cvi]

In 1800, during the rule of Napoleon, he returned to France and resided at Bordeux, where he lived a relatively quiet life, but remained active, travelling to Paris to pay his respects to Pope Pius VII in 1805 and working to rehabilitate the Irish College in Paris after its closure during the anti-clerical Revolutionary period.[cvii] Following the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy after the fall of Napoleon, he was appointed a Privy Councillor and Minister for Public Instruction by King Louis XVIII and in recognition of his loyalty to the monarchy was created on 19th August 1815 Marquis of Lally-Tollendal and a Peer of France.[cviii]

He was elected as a member of the prestigious French Royal Academy in 1816 and invested as a Knight Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour and a Knight Commander and Grand-Treasurer of the Order of the Holy Ghost.[cix]He committed himself to various good works such as prison reform in later years and died in March 1830 from a stroke of apoplexy.[cx]

He married Elizabeth Charlotte Wedderburn Halkett, by whom he had one daughter and heiress, Elizabeth Félicité Claude de Lally Tolendal. She married the Count d’Aux and the Lally title passed to the Count d’Aux on the death of Trophime Gerard.[cxi]

Other Lallys established in France

With regard to the family of Michael, younger brother of Sir Gerard Lally, bart., this Michael had five sons and five daughters. His son Michael, born in 1714, left Ireland in 1734 and joined Dillon’s Regiment. In 1744 he was a captain in Lally’s Regiment, commanded by his cousin Thomas Arthur, and after the battle of Fontenoy was promoted to Colonel and Brigadier General in the French service. He also served with his cousin in his service in India ‘where he was his constant companion during the many vicissitudes of a strenuous campaign.’[cxii]Returning to France in 1762 he died at Rouen in 1773.[cxiii] A grandson of this latter Michael, named Joseph Stanislaus Lally de la Neuville, was born about 1813 and four years old and living in France in 1817.[cxiv]

The Lallys of Milltown and Grange

The family of William, apparently the third son of Thomas Lally and Jane Dillon, was established in Ireland. This William was said in the pedigree to have been the ancestor of the Lallys of Milltown and Grange in County Galway. In 1777 Hawkins Ulster gave one James Lally of Milltown, Esq. as head of this branch of the family. James was given as the eldest of three brothers, the second, Thomas, described in 1777 as ‘an old friar’. The youngest of the three was Patrick Lally, who was said at that time to have been the father of two sons.[cxv]

James of Milltown was said to have married a daughter of H. Kirwan of Balligady, near Tullenadally, Esq. and had a son, named Thomas, born about 1761.[cxvi] This Thomas, born in 1761, appears to have been the Thomas Lally of Tuam who visited his relative the Marquis de Lally-Tolendal between 1823 and 1825. As the Marquis was without a son and Thomas was the eldest of the line descended from the third son of Thomas Lally and Jane Dillon, he would be the next senior member of the family following the death of the Marquis. He visited the Marquis between 1823 and 1825 and was well received, returning to Ireland with mementos such as ‘silver cups and flagons, etc., an engraving of the coat of arms of the Lallys and a portrait of the Marquis.’[cxvii]

Thomas Lally of Tuam, however, died without issue in May 1837, seven years after the death of the Marquis.[cxviii] Denis H. Kelly of Castlekelly, near Ballygar in County Galway, informed the antiquary John O Donovan in the mid nineteenth century that Thomas had a brother whose son Thomas also died unmarried and without children in 1838. Kelly described this latter Thomas as ‘the last survivor of the male line of this very ancient family in this kingdom.’[cxix]

Despite Kelly’s description, it is unlikely that the Thomas Lally who died in 1838 was the last of the Lallys descended from Thomas Lally and Jane Dillon left in Ireland. Kelly did not make any reference to the sons of Patrick Lally, younger brother of the James of Milltown.

In addition, as Michael, younger brother of Sir Gerard Lally, bart. had five sons, it is unclear if any of those other than Michael the younger went to France and, if settled in Ireland, may have had surviving descendants.

Rev. Dr. Lally of England

Another Lally visited the Marquis before his death. The Rev. Dr. William Michael Lally, a Protestant Clergyman, Rector of Drayton Bassett in Staffordshire in England called upon the Marquis in 1826, believing himself to be possibly related. The Marquis consented to Lally making a copy of the pedigree, who engaged Sir William Betham to examine the same with a view to ‘finding his own diverging ancestor.’[cxx]

The clergyman was a son of Rev. Edmund Lally, vicar of Whitegate, Cheshire and brother of Edmund, who pursued a military career in the British army, serving in the Peninsula War as a Captain in the 4th Dragoon Guards.[cxxi] Their father, the Rev. Edmund Lally was a Fellow of St. Peter’s College, Cambridge and Vicar of Whitegate from 1772 to 1826. He died in 1826.[cxxii] The Rev. Dr. W.M. Lally said that his grandfather was Michael Lally but was unaware of the identity of Michael’s father. He was of the opinion that his great-grandfather may have been Edward, as he found an Edward Lally living in England in 1707-8, at which time his son, named Michael, was born. He was also said to have considered that he was descended from Mark Lally, younger son of Thomas Lally and Jane Dillon, who he held may have left France for England and had a son by a Miss Bushill, by whom he had a son Michael born about 1707-8. His great grandfather, he said, had twenty-two children. [cxxiii] The Hawkins pedigree, however, did not refer to descendants of this Mark Lally, brother of James, Gerald, William and Michael.

It is uncertain if he identified his ancestor connecting him to the pedigree but in 1830 he visited Galway, staying at Eyre Square with his relatives Anthony Martyn and V. Rev. Andrew Henry Martyn Parish Priest of Carrabrown and Vicar of Galway, sons of Henry Martyn, Windsor, Castlebar, County Mayo and of his wife Bridget Lally ‘of the old Tullinadaly stock.’ [cxxiv] The Marquis later related that on that occasion Rev. Dr. Lally and the Very Rev. Andrew Henry Martyn PP visited the Franciscan Abbey at Galway ‘and there identified the Lally tomb.’ [cxxv] The Lally tomb in question may have been a reference to the tomb of Thomas O Mullally, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Tuam from 1514 to his death in 1536 and who was buried at the Franciscan friary at Galway in the same tomb as his immediate predecessor Maurice O Fihely.[cxxvi]

The Rev. Dr. William Michael Lally was for nearly sixty years rector of Drayton Bassett, having been presented there in 1799 and died there on the 15th June 1857 aged 81. There is a monument to him in the church erected by the parishioners. Married twice and had four sons and three daughters by his first wife. [cxxvii] His brother, Captain Edmund Lally, 4th Dragoon Guards, died in July 1853.[cxxviii]

Conversions to Protestantism

Two Lallys were recorded as having converted to Protestantism in Ireland in the eighteenth century. Michael Lally with an address in Dublin conformed to Protestantism in March of 1721 and also occurred with an address in Ardfry, Co. Galway, while one Edward Lally, without any address given, converted in mid December 1788.[cxxix]

The Lally Monument, Ballytrasna, Tuam

At least two physical monuments remain commemorating the leading branch of the name in the two countries with which they are most associated. In memory of Trophime Gerard, Marquis and Compte Lally-Tollendal, a street in the Polish quarter in Paris was named the ‘rue Lally-Tollenal’, while, on a stone mound situated in a field near the roadside in the townland of Ballytrasna, between the town of Tuam and Tullaghdaly, a seventeenth century stone tablet is inset bearing the words ‘IHS Pray for the souls of James Lally and his family 1673.’ [cxxx]

[i] Knox, H.T., The Early Tribes of Connaught: part 1, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth series, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1900, p. 349; Mannion, J., The Senchineoil and the Sogain: Differentiating between the Pre-Celtic and early Celtic Tribes of Central East Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 58, 2006, pp. 166, 168; O Donovan, J. (ed.), Leabhar na g-ceart or The Book of Rights, Dublin, M.H. Gill, for the Celtic Society, 1847, p. 106.

[ii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 32-3; 177.

[iii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 32-3.

[iv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 32-3;Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. II, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, p. 63. No. 328.8.

[v] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 32-3.

[vi] O Flaherty, R., Ogygia: or, A chronological account of Irish events: collected from very ancient documents, (translated by Rev. James Hely), Vol. II, Dublin, W. M’Kenzie, 1793, Part III, Chapter LXVI, p. 146. ‘O Neachtain agus O Maoilaloidh, da thighearna Maonmhuighe.’

[vii] Egan, P.K., Extant of Maonmagh, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 35, 1976, pp. 154-5.

[viii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 175-7.

[ix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 175-7.

[x] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 175-7.

[xi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 178-180.

[xii] Bliss, W.H. and Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 6: 1404-1415, London, (1904), Vatican Regesta 169: 1413-1414, pp. 422-430.

[xiii] Twemlow, J.A., (ed.) Calendar of Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 8: 1427-1447, London, (1909), Vatican Regesta 282: 1427-8, pp. 50-62.

[xiv] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell (continued), J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 2, 1902, p. 5.

[xv] Biggar, F.J., The Franciscan Abbey of Kilconnell (continued), J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 2, 1902, p. 5.

[xvi] Blake, M.J., Notes on the Persons Named in the Obituary Book of the Franciscan Abbey at Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 7, No. 1, 1911, p. 16.

[xvii] McNicholls, K.W., Visitations of the Dioceses of Clonfert, Tuam and Kilmacduagh, c. 1565-67, Analecta Hibernica, No. 26, 1970, pp. 144-157.

[xviii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 70-71 (footnotes a, b.), 178.

[xix] N.L.I., Dublin, G.O. Ms. 79 Funeral Entries, p. 84; Blake, M.J., Notes on the Persons Named in the Obituary Book of the Franciscan Abbey at Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 7, No. 1, 1911, p. 16.

[xx] Blake, M.J., Notes on the Persons Named in the Obituary Book of the Franciscan Abbey at Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 7, No. 1, 1911, p. 16; N.L.I., Dublin, G.O. Ms. 79 Funeral Entries, p. 84. In his Funeral Entry ‘Isaack O Mullolly of Tulloghdaly’ is described as ‘eldest son and heir of the Most Revd. Father in God William O Mullolly, Archbishop of Tuam, eldest son and heir of the Most Revd. Father in God Thomas O Mulloy, Archbishop of Tuam, afforesaid descended from Maylfalla O Kelly, second son of O Kelly of Atherin.’

[xxi] Calendar Patent Rolls, 2 James I, p. 64.

[xxii] Calendar Patent Rolls, 1 James I, pp. 18-20, 28.

[xxiii] Calendar Patent Rolls, 1 James I, pp. 18-20, 28.

[xxiv] Calendar Patent Rolls, 16 James I, p. 369.

[xxv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 178.

[xxvi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 178.

[xxvii] Calendar Patent Rolls, 16 James I, p. 369.

[xxviii] Calendar Patent Rolls, 16 James I, p. 369.

[xxix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 178.

[xxx] Calendar Patent Rolls, 16 James I, p. 371.

[xxxi] Blake, M.J., Notes on the Persons Named in the Obituary Book of the Franciscan Abbey at Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 7, No. 1, 1911, p. 16.

[xxxii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183; N.L.I., Dublin, G.O. Ms. 79 Funeral Entries, p. 84.

[xxxiii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[xxxiv] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 286-9. The name was given therein as Lawlys and Lawless.

[xxxv] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 286-9.

[xxxvi] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 134-5.

[xxxvii] N.L.I., Dublin, G.O. Ms. 79 Funeral Entries, p. 84; O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[xxxviii] Simington, R.C., The Transplantation to Connacht 1654-58, Shannon, Irish University Press, for the I.M.C., 1970, p. 120.

[xxxix] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 284.

[xl] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[xli] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[xlii] Simington, R.C., The Transplantation to Connacht 1654-58, Shannon, Irish University Press, for the I.M.C., 1970, p. 118.

[xliii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, pp. 134-5; 286-9.

[xliv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[xlv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[xlvi] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 340, no. 2946.

[xlvii] Martyn, J., The Sept of O Maloale (or Lally) of Hy-Maine, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, no. iv, 1905-6, pp. 203-4.

[xlviii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[xlix] J. D’Alton, Illustrations, historical and genealogical of King Jame’s Irish Army List 1689, Published by author for the subscribers, Dublin, 1855, p. 582.

[l] J. D’Alton, Illustrations, historical and genealogical of King Jame’s Irish Army List 1689, Published by author for the subscribers, Dublin, 1855, p. 617.

[li] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 75; hAnnracháin, E., Some Wild Geese of the West, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 54, 2002, p. 1. In France the three regiments were formed from the five, those of Mountcashel, O Brien and Dillon, forming one Irish brigade known as the Mountcashel Brigade.

[lii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[liii] Simms, J.G., Irish Jacobites, Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, 1960, p. 72.

[liv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[lv] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 70.

[lvi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[lvii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, pp. 124-5, nos. 1107, 1108, 1109.

[lviii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, pp. 124-5, nos. 1107, 1108, 1109.

[lix] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 158, no. 1476.

[lx] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 99, no. 899.

[lxi] J. D’Alton, Illustrations, historical and genealogical of King Jame’s Irish Army List 1689, Published by author for the subscribers, Dublin, 1855, pp. 594-600.

[lxii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 284.

[lxiii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 315, no.2725.

[lxiv] Simms, J.G., Irish Jacobites, Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, 1960, p. 98, no. 111v.

[lxv] Ó hAnnracháin, E., A Galway scion in India, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 57, 2005, p. 24, Appendix II. Gerard Lally was described on the registration of the marriage as the legitimate son of the late noble Thomas Lally, lord and baron of Tollendaly in Ireland, and of lady Jeanne Dillon.’

[lxvi] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 73-4.

[lxvii] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120; Ó hAnnracháin, E., A Galway scion in India, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 57, 2005, p. 24, Appendix III. Thomas Arthur was described at the registration of his baptism as the legitimate son of Gerard and Anne Marie.

[lxviii] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 73-4.

[lxix] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 73-4.

[lxx] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[lxxi] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, pp. 126-7.

[lxxii] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, pp. 126-7.

[lxxiii] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 71.

[lxxiv] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[lxxv] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, p. 129.

[lxxvi] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 76.

[lxxvii] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 76.

[lxxviii] Owen, S. J., Count Lally, The English Historical Review, Vol. 6, No. 23, 1891, p. 499-500.

[lxxix] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[lxxx] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 76.

[lxxxi] Owen, S. J., Count Lally, The English Historical Review, Vol. 6, No. 23, 1891, p. 499-500.

[lxxxii] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[lxxxiii] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[lxxxiv] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, pp. 137-8.

[lxxxv] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, pp. 153-4.

[lxxxvi] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 78.

[lxxxvii] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, p. 158.

[lxxxviii] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, p. 159.

[lxxxix] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, p. 160.

[xc] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, pp. 160-1.

[xci] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[xcii] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 81.

[xciii] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, p. 161.

[xciv] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 81.

[xcv] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, p. 162.

[xcvi] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 81.

[xcvii] Ainsworth, W.H., The New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 127, London, Chapman and Hall, 1863, ‘Seven Generations of Executioners, pp. 272-3. The executioner Sanson was personally known to Lally and would later execute King Louis XVI.

[xcviii] Malleson, G.B., Lecture on the career of Count Lally, delivered in the Dalhousie Institute, Calcutta, India, 16th January 1865, Essays and Lectures on Indian Historical Subjects, London, Trüber & Co., 1866, p. 162; Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 81.

[xcix] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 83; Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 72.

[c] Ó hAnnracháin, E., Lally, the Régime’s Scapegoat, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 56, 2004, p. 83.

[ci] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 72. Captain Drumgoole was sent by the Countess to inform the boy of the execution.

[cii] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 72.

[ciii] Hanson, P. R., Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution, Oxford, Scarecrow Press Ltd, 2004, p.173.

[civ] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[cv] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 72.

[cvi] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 72.

[cvii] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 73.

[cviii] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120; Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 73.

[cix] Marquis of Ruvigny and Raineval, The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour, Edinburgh, T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904, pp. 119-120.

[cx] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 73.

[cxi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[cxii] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 70.

[cxiii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183; Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 70.

[cxiv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[cxv] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183.

[cxvi] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, pp. 177-183. This Thomas Lally was said in the pedigree to have been aged sixteen years in 1777.

[cxvii] Martyn, J., The Sept of O Maloale (or Lally) of Hy-Maine, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, no. iv, 1905-6, pp. 208-210;

[cxviii] Martyn, J., The Sept of O Maloale (or Lally) of Hy-Maine, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, no. iv, 1905-6, pp. 208-210;

[cxix] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many, commonly called O Kelly’s Country, Irish Archaeological Society, Dublin, 1843, p. 182.

[cxx] Martyn, J., The Sept of O Maloale (or Lally) of Hy-Maine, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, no. iv, 1905-6, pp. 208-210;

[cxxi] Finch Smith, Rev. J., The Admission Register of the Manchester School, Remains Historical and Literary connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester, Vol. LXIX, The Chetham Society, 1866, p. 165. Catherine, daughter of Rev. Edmund Lally, vicar of Whitegate, Cheshire, and sister of Rev. W. M. Lally, Rector of Drayton Bassett, married William Bankes of Winstanley, Lancashire. Catherine was Banke’s first wife and Bankes married again, his second wife dying in 1798. (Finch Smith, Rev. J., The Admission Register of the Manchester School, Remains Historical and Literary connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester, Vol. LXIX, The Chetham Society, 1866, p. 91.)

[cxxii] Finch Smith, Rev. J., The Admission Register of the Manchester School, Remains Historical and Literary connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester, Vol. LXIX, The Chetham Society, 1866, p. 150.

[cxxiii] Martyn, J., The Sept of O Maloale (or Lally) of Hy-Maine, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, no. iv, 1905-6, pp. 208-210;

[cxxiv] Martyn, J., The Sept of O Maloale (or Lally) of Hy-Maine, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, no. iv, 1905-6, pp. 207-210;

[cxxv] Martyn, J., The Sept of O Maloale (or Lally) of Hy-Maine, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, no. iv, 1905-6, pp. 207-210;

[cxxvi] Blake, M.J., The Obituary Book of the Franciscan Monastery at Galway: With Notes Thereon, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 6, No. 4, 1910, p. 231.

[cxxvii] Finch Smith, Rev. J., The Admission Register of the Manchester School, Remains Historical and Literary connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester, Vol. LXIX, The Chetham Society, 1866, p. 150; Urban, S., The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review, Vol. III New Series (and Vol. 203), London, John Henry and James Parker, 1857, p. 99.

[cxxviii] Finch Smith, Rev. J., The Admission Register of the Manchester School, Remains Historical and Literary connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester, Vol. LXIX, The Chetham Society, 1866, p. 165.

[cxxix] Byrne, E. and Chamney, A. (ed.), The Convert Rolls, the Calendar of the Convert Rolls, 1703-1838 with Fr. Wallace Clare’s annotated list of converts, 1703-78, Dublin, IMC, 2005, p. 144.

[cxxx] Hayes, R., Biographical Dictionary of Irishmen in France, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 33, No. 129, 1944, p. 73.