© Donal G. Burke 2013

A brief history of O Madden’s country in East Galway

Continued from ‘Fifteenth Century.’

Ireland at the start of the sixteenth century.

‘Fearann claíomh’ or ‘sword land’ was how one Gaelic poet described sixteenth century Ireland. At the beginning of the century only a small area about Dublin, known as the Pale, was under English law. Elsewhere, Gaelic law and customs prevailed in varying degrees. Even in a lordship ruled by those of Anglo-Norman descent, such as Clanricard, Gaelic law was adhered to. The country was divided into a myriad of lordships, many hostile to their neighbouring territories and bound to others in various alliances, with little or no reference to the Crown or a central government. Each chieftain or lord of these territories, in the eyes of one contemporary Englishman, ‘maketh war and peace for himself without any licence from the king, or of any other temporal person, save to him that is strongest, and of such that may subdue him by the sword.’ Cattle were still the essential unit of currency and symbol of wealth, and the core landholding entity in these areas was the extended family.

The structure of society in the Gaelic lordship

At the top of society in Síl Anmchadha, as in other Gaelic lordships, was the ruling chieftain and his extended family. In addition to those lands that were held by the chieftains own extended family, certain lands and castles, called chiefry castles, within the lordship, were attached to the position of chieftain and were held by him for the duration of his rule. Other lands were also attached to the position specifically for the provisioning of the chieftain. His position was an elected one, open to the descendents within four generations of a previous chieftain. Invariably the position was taken by that individual within the ruling family with the strongest political and military support, usually the most senior of the family, ‘for the most part, not the eldest sonne, nor any of the children of ther lord deceased, but the next to him of blood, that is, the eldest and worthiest, as commonly the next brother unto him, if he have any, or the next couzine germane, or so forth.’[i] His efficacy in the role was gauged by his ability to exact those privileges and dues from his people, which were his by right of Gaelic law, and to defend his territory from the raids of neighbouring lords. As succession to the chieftaincy was confined to the members of the one larger family, this resulted in a ruling house constantly divided against itself in the struggle for power of individual branches of the extended family.

The position of tánaiste was that of prospective chieftain, recognised by the chieftain during his lifetime as his successor. With this office was associated certain lands and castles also, and was often, though not always, held by the most senior member of that branch of the ruling extended family out of power. The position to some degree was often intended to serve as a pacifier to the next strongest branch after the chieftains, with the implication that on the demise of the chieftain the chieftaincy would pass to them.

Irrespective of his external relations with more powerful neighbouring lords, within his own territory the power of a chieftain secure in his position was absolute. Those at the lower strata of society suffered heavily from the burden of exactions and privileges due to the chieftain and the principal families. Apart from its aristocratic structure, the very nature of Gaelic society was diametrically opposed to that of the country that claimed overlordship over her. If England was ever to consolidate its hold on Ireland, the Gaelic chieftains and landholders would have to be forced or persuaded to recognise the kings authority, renounce their culture and legal system, accept a diminution of their military and political power and agree to hold their lands under English law.

The principal constituent families of the territory

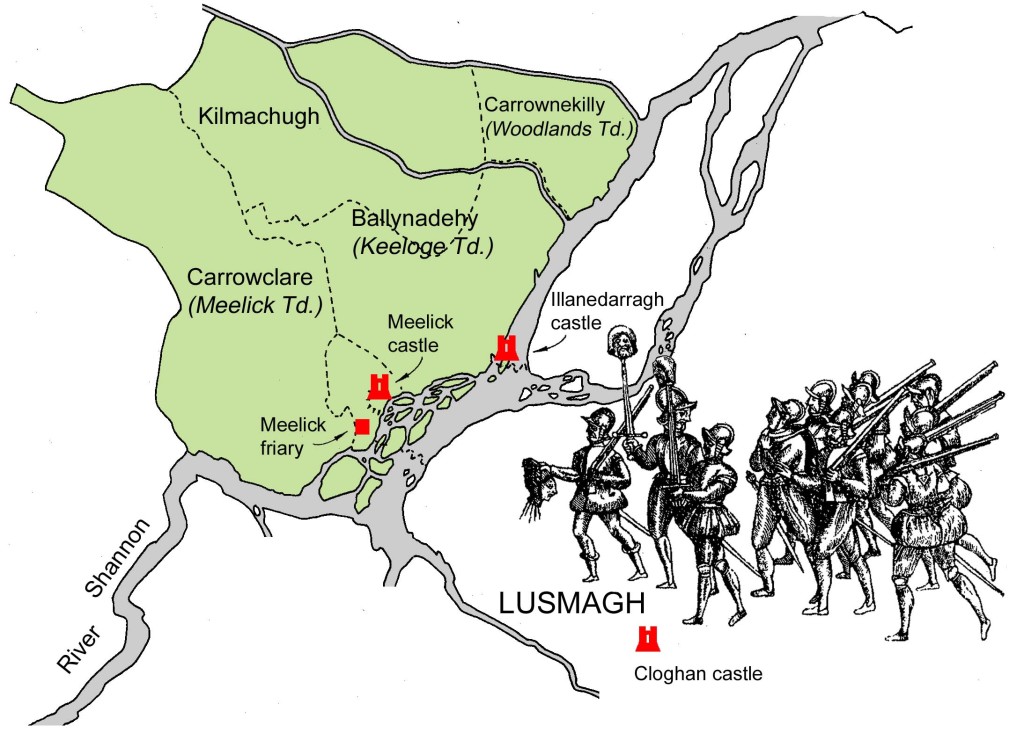

The principal chiefry castle in Síl Anmchadha appears to have been Longford, in the parish of Tiernascragh. In the absence of any permanent English presence in the territory, the principal castle at Meelick may also have been attached to the office of the chieftain. In any event, it was in the ‘custody’ of O Madden early in the sixteenth century. Services and customs were due to the chieftain from the principal branches and sub-septs of the O Maddens themselves and from the four main constituent families within the lordship; the O Horans, MacCoulahans, O Treacys and O Larkins. (All of this latter group, with the exception of the O Treacys, located further south about Killimorbologue, served as benefactors of the Franciscans at Meelick and provided brothers to that friary.)

Of those constituent families, the O Horans held the highest status. Their ancestral lands, referred to in one contemporary record as ‘O Horan’s country’, covered an area approximate to the later parish of Fahy, adjoining Meelick. The seven quarters of the medieval parish of Moynterorrane or muintir Ui Odhrain reflected their traditional lands, and, excluding the quarter of Feabegg, (which was regarded separately in the 1585 indenture of O Maddens country), corresponded to the parish of Fahy as it stood in the middle of the following century. The head of the family resided at Fahyhoran, wherein stood the castle of Carrowanclogha.[ii] Within their territory, adjoining Carrowanclogha, lay the area known as Tullinlicky or ‘tullach an leiche’, the hill of the stone slab’. A combination of factors, geographical location, local folklore and the status of the O Horans within Sil Anmchadha, would suggest this to be a possible reference to the ancient inauguration site of the O Madden, and indicating that the O Horans may have played a foremost role in the inauguration of the O Madden chieftain.

The MacCoulahans lands lay in Lusmagh, across the Shannon from Meelick, about Ballymaccoulahan, while the Larkins ancestral lands lay centred on the townland of Craughwell in the parish of Kiltormer. Another constituent family closely connected to Meelick was that of the Callanans, whose lands lay about Grange in the parish of Fahy and whose ancestral role may have been that of physicians. Scions from these local families and from those bordering the lordship provided religious to the friary at Meelick and ecclesiastics to the diocese and monastic foundation at Clonfert. The Church itself was a considerable landholder in O Maddens country, and, while the Franciscans at Meelick were not prominent in this regard, the Augustinian monastery at Clonfert held extensive abbey lands in the immediate vicinity about the Cathedral, its town and about the foot of the nearby Knockmoydarregg or Redmount Hill, which dominated the surrounding landscape.

The ascent of the Tudors

Successive English kings, since the decline of the Anglo-Norman colony, paid little attention to Irish affairs, concerned instead with internal English and continental wars. The government of Ireland was left in the hands of the Kings more powerful Irish nobles of Anglo-Norman descent. However, with the ascent to the English throne of the Tudor family, in the person of Henry VII, this altered. The history of Ireland in the sixteenth century is essentially that of the concerted attempts of Henry’s son, King Henry VIII, and his successors, to complete the conquest of Ireland and to finally bring the country under English control.

The Reformation

Throughout the previous century several Church councils, concerned at the decline in morality and spirituality among the religious, met on the Continent, in support of reformation of the hierarchy and practices. A monk and theologian, Martin Luther, had come to prominence in Germany among those seeking reform.

Excommunicated by the Pope and outlawed by the Holy Roman Emperor, Luther found protection with the Prince of Saxony. Many of the monarchies in Europe were eager to rid themselves of the influence of the Pope in their own domestic and foreign political affairs. The Reformation movement spread throughout Europe, and found favour in such kingdoms and states as Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland.

In England, King Henry VIII had fallen out with the Pope over the Popes refusal to grant Henry an annulment of his marriage. Discontent with the Church was increasing in England, where many were unhappy paying taxes to the Pope and with the obvious wealth and vast property of the Church. Henry broke with the Church and in 1534 had his Parliament pass the Act of Supremacy, making the King and his successors the supreme head of the Church in England. Payments to the Catholic Church and appeals to Rome would be forbidden under later Acts. Henry and his officials set about the dissolution of monasteries and the confiscation of the rich Church property, selling them on to bolster the Crown coffers. From 1537 to 1541, many Irish monasteries were suppressed and their lands sold off.

Surrender and Regrant

In the early 1500s, King Henry VIII broke the grip of the then most powerful Anglo-Irish family, the FitzGeralds of Kildare, on the government of Ireland. Henceforth, in line with Tudor policy, to prevent the possibility of powerful Anglo-Irish nobles dominating Irish politics and acting in their own interest, the government of the kingdom of Ireland would be placed in the hands of English officials acting for the King.

Henry adopted a conciliatory approach to Irish and Anglo-Norman chieftains, in an effort to bring them peacefully under his influence, and avoid endless and costly wars. The Crown offered those chieftains it approached legal title under English law to their lands. The chieftains would surrender their lands to the King and their right to rule under Gaelic law, recognise the King’s authority and receive their lands back at the hands of the King, as his loyal vassals. In accepting this regrant the chieftains ensured the succession to the chieftaincy would now follow the English system of primogeniture, the chief’s lands going directly to the eldest son, instead of the Gaelic system of election of the fittest to rule. An agreement with the Crown also ensured the intervention of English troops on the side of the loyalist. Although the English government kept very few soldiers in the country in the early part of the century, their intervention on the side of a candidate in a succession dispute could be a decisive factor in his attaining or retaining the chieftaincy.

The first Earl of Clanricarde

Internal politics within Clanricarde, the territory immediately to the west and southwest of O Madden’s country, would have major ramifications for Síl Anmcadha and the rest of Connacht in the late medieval period. Clanricarde as a geographical area covered a large portion of what would later be County Galway, the chieftainship of which was that of the Burkes, partly-gaelicised descendants of the Red Earl’s cousin Sir William liath de Burgh, whose chieftain took the Gaelic title of The Upper MacWilliam Burke. There, Ulick ‘na gceann’ Burke succeeded to the chieftaincy of Clanricard in 1538 with the help of the English Lord Deputy, to whom he submitted. His submission was important for the King, as his territory was extensive and if he and his successors were to remain loyal, they would provide the English administration, only beginning to establish a significant presence west of the Shannon, with a valuable ally in Connacht. In seeking the King’s pardon he took the opportunity of seeking possession of the castle of Meelick, then in the custody of O Madden.

For aligning himself with King Henry, Ulick ‘na gceann’ was created 1st Earl of Clanricarde and Baron of Dunkellin in 1543 and received a re-grant of his estates at the king’s hand. In addition to securing the lordship lands for his own immediate descendants under English law, the re-grant provided his family with legal title to their estates that, under English law, had rightly been the property of the descendants of the Brown Earl’s daughter. Ulick, however, died not long thereafter. He was succeeded eventually, again with the assistance of the English administration, by his son Richard ‘sassanach’ Burke.[iii] With the second Earl initially acting intermittently in the interest of the King in the years immediately following his acquisition of the title, the increasing power of the Crown was being sorely felt throughout Connacht. In this, however, the Earl was vigorously opposed by those within and without his lordship who refused to accept the imposition of English law and influence.

Politics in early sixteenth century O Madden’s Country

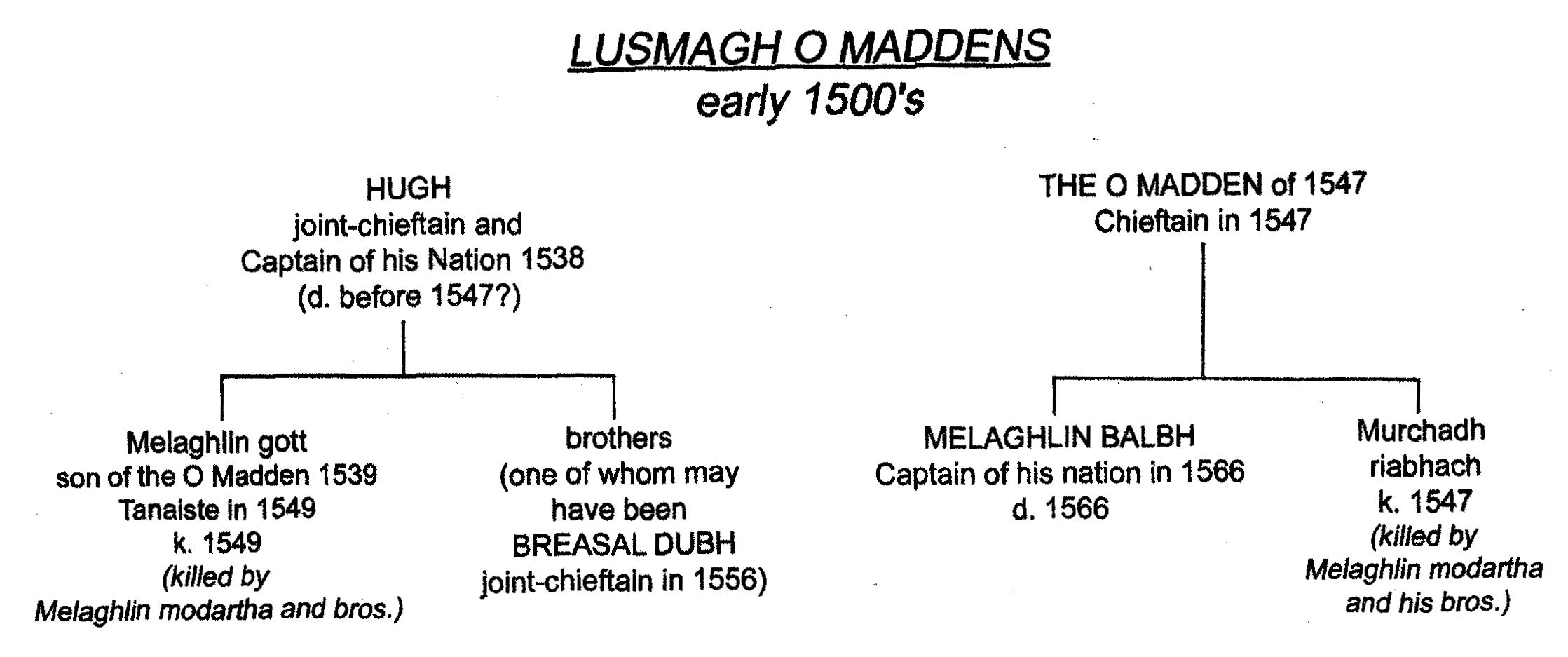

With regard to the O Madden territory at this time, it was not uncommon in Gaelic lordships, when two rival factions within the ruling extended family grew equally strong, and neither was in a position to overthrow the other, that the office of chieftain was held jointly between the principal representatives of both factions simultaneously. This occurred in Síl Anmchadha at least twice in the sixteenth century. In 1526 the chieftain, Breasal O Madden, died and it appears two rivals vied for the chieftaincy, Breasal’s son, Melaghlin and one Hugh O Madden.[iv]

In the summer of 1538, the Lord Deputy Leonard Gray travelled through Connacht and both men presented themselves before him at Galway.[v] Both submitted at Galway to the King’s authority and each gave a son as hostage.[vi] After leaving Galway and travelling to the borders of O Kellys’ territory, Grey progressed southwards through O Madden’s country, ‘receiving from the two O Maddens three score kine’ and crossed the River Shannon at the ford of Banagher.[vii] Both men appear to have been regarded as joint chieftains in the territory and acted as such. While Hugh is described on one occasion in the Lord Deputy’s correspondence as ‘chieff capitayn of his countre called Sylmghnee’, both are elsewhere treated equally by the Lord Deputy.[viii] The Lord Deputy would also enter into an Indenture with both Melaghlin and Hugh separately and simultaneously in which each is called ‘capitayne of his cuntrey’ and in which they agreed to pay an annual sum to the King from their lands and provided eighty galloglass to serve the King’s needs for the term of a fortnight.[ix]

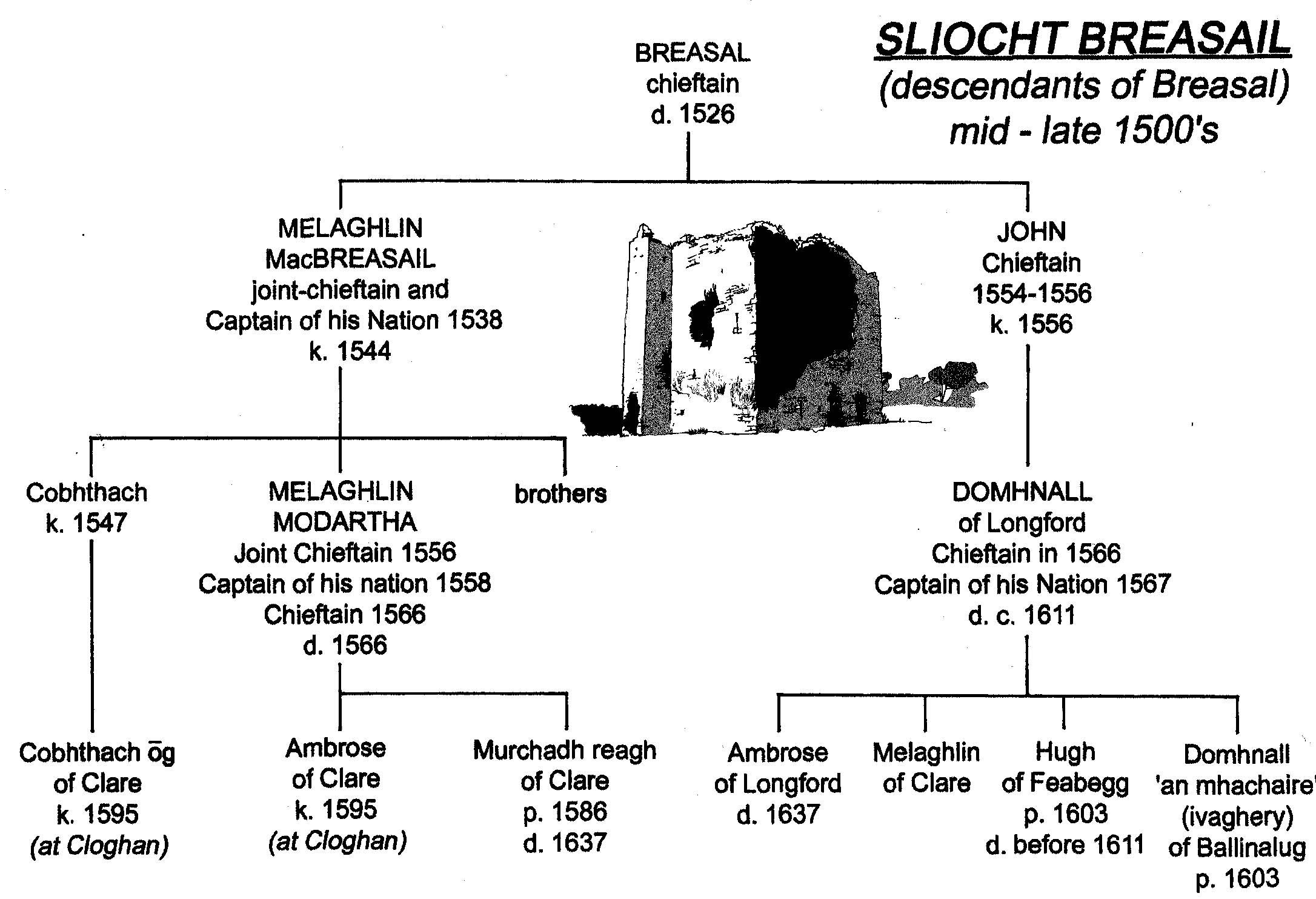

The descendants of Breasal, of whom Melaghlin mac Breasail (ie. ‘Melaghlin son of Breasal’) was the most senior, were collectively referred to as the ‘Sliocht Breasail Uí Mhadadhain’ (ie. ‘the progeny of Breasal O Madden’) and appear to have been seated about the parish of Kilquain, where Breasal’s grandson later held the castle of Clare or Claremadden.[x]

Both factions held the joint-chieftaincy in an uneasy balance until, in 1544, Melaghlin macBreasail was killed by Melaghlin gott ‘the stammerer’, a son of Hugh O Madden.[xi] The killing fuelled a bitter power struggle between the two rival branches of the O Maddens. In killing Melaghlin macBreasail, Melaghlin gott’s branch gained the upper hand in the lordship for a time. Melaghlin gott survived a raid in 1546 by the Sliocht Breasail in conjunction with the O Kelly, to still be in a position to plunder the territory of the O Donnellans, on the north western border of Síl Anmchadha, the following year and take from them a prey of five hundred cows.

The violence intensified in 1547, when, together with the O Carrolls, the people of Melaghlin balbh ‘the silent’, son of the then O Madden, killed a young scion of the Sliocht Breasail; Cobhthach, son of the slain Melaghlin mac Breasail.[xii] In retaliation, Cobhthach’s brothers hanged Melaghlin balbh’s brother, Murchadh riabhach, whom Cobhthach’s people had been holding prisoner in chains. Both corpses were interred simultaneously.

At least one of Melaghlin balbh’s sons was closely associated with the parish of Lusmagh and based at Cloghan Castle therein and it is possible that Melaghlin balbh may have been principally based about that area at one time. He found it more politically expedient at this time to side with the Government, which saw him providing support to the English in September of 1548 while the O Kelly was conspiring to make war on the King.[xiii] However, within a month the English were doubtful as to his continuing loyalty, reporting that he ‘begineth to be prowde.’ Despite their father’s sometime alliance with the English, most of the sons of Melaghlin balbh O Madden, whose descendents would be disenfranchised under English laws of inheritance, would be at odds with the English for much of the latter half of the century.[xiv]

The struggle between the Sliocht Breasail and Melaghlin gott came to a head in 1549, when Melaghlin modartha O Madden and his brothers, (sons of Melaghlin macBreasail) killed Melaghlin gott, then tánaiste or heir designate of Síl Anmchadha, ‘a n-diocchail a athar agus a dherbrathar’ (‘in revenge for his father and brother’). As it was the people of Melaghlin balbh who killed Melaghlin modartha’s brother, Cobhthach, and as it was in part revenge for Cobhthach’s death that the Sliocht Breasail killed Melaghlin gott, it would appear that Melaghlin gott himself was ‘of the territory of Lusmagh.’

The chieftaincy was held sometime thereafter by one Hugh or Aodh macAnmchadh O Madden until his death in 1554, whereupon John son of Breasal O Madden became chieftain. John is given by the nineteenth century antiquary John O Donovan as the son of the chieftain slain in 1526 and uncle to Melaghlin modartha and therefore of the Sliocht Breasail.

John’s time in office was cut short, however, when he was killed two years later by Breasal dubh ‘the black’ O Madden. Breasal dubh had not sufficient internal support to assume the chieftaincy alone, and two chieftains were again proclaimed in Síl Anmchadha, Breasal dubh and Melaghlin modartha O Madden. Breasal dubh was resident at Cloghan castle in the following year and may have been of the Lusmagh branch, while Melaghlin modartha represented the interests of the Sliocht Breasail Uí Mhadadhain.

Colonisation and plantation

Under King Henry’s daughter, the devoutly Catholic Queen Mary I, a policy of colonisation was initiated as a means to further the anglicisation of Ireland. Rebel lands were to be confiscated and planted with loyal English or Scottish settlers. The territories of the O Moores and O Connors in Laois and Offaly, long a threat to the security of the Pale, were taken and a plantation organised. Two counties were to be formed from the territories; Laois, to be known as Queens County, and Offaly, Kings County, after Mary’s husband, King Philip of Spain.[xv]

The retaking of Meelick Manor by the Crown 1557

Rebel O Connors from the Midlands found succour and refuge at Meelick Castle among those of the O Maddens opposed to the increased influence of English influence in Connacht. In the summer of 1557 the English Lord Deputy moved against the Meelick insurgents. Leaving Kilmainham on Saturday 10th July, the Lord Deputy Sussex and his troops came by O Molloy’s country. Entering Sil Anmchadha, they passed by Cloghan Castle, ‘wherein was Dermouth O Madden and Brazell Doehe (dubh) O Madden’ who appeared before the Deputy on his command. On Monday the 12th July, the Lord Deputy came before the Castle of Meelick. ‘As the Deputy came towards the said castle of Mulbicke (sic)’ an eye-witness recorded later, ‘he went to peruse the same with his horsemen on the plain; and as he rode up and down, they of the castle made 4 or 5 shots with handguns or pieces, and he departed towards his camp, and they of the castle that stood within the river likewise shot 2 or 3 pieces at us. News being brought that the ordnance was come within a mile or two of the camp, his lordship commanded it to be brought to him with speed. Soon after, they of the little castle on the Sennon set fire on their castle, and went to the castle of Mulbicke’.[xvi]

The following day, ‘the Deputy removed his camp, and went over the water of Sennon accompanied with Sir George Stanley, Knight Marshal, Sir Henry Radcliffe, Lieutenant, Mr. Francis Aggard of the Privy Council and the Captains of the footmen, as Mr. Humfrey Warren, Mr. Thomas Smith, Mr. Henry Colle and their footmen, and Mr. Strannge, sub-constable of the castle of Athloone, with his kerne, who came with great ordnance by water. He rode first to the abbey or friary, nigh to the castle of Mulbicke, to peruse the same, and there, Thomas Barrett, a soldier under Captain Warraunt, was hurt with a handgun out of the castle of Mulbicke. After his lordship had remained in the said friary a little while, he returned over the water again. After dinner he sent me, Athlone pursuivant, to Gallway, for victuals and munitions. He then caused the great ordnance to be landed, and caused the little wood to be cut and the way to be made, that the great ordnance might be carried to the castle of Mulbicke. Ere night fell, he had brought one piece of ordnance to the friary and there planted it somewhat aslope, and shot it off once as a warning piece. Then he sent a messenger, Henry Colle, commanding them to deliver the castle into the hands of the King and Queen. They replied that they could give no answer until they knew their masters pleasure, and desired respite until the morrow morning, to which his lordship agreed, and all that night, he caused the ordnance to be planted straight against the castle.’

The next day, ‘he sent the messenger again to the castle to know their mind. They sent word that they would defend the castle, and willed the messenger to come with no more messages. Then his lordship commanded the great ordnance to be shot off, and within 16 shots a great piece of the wall of the Banne (bawn) fell down; and then, immediately after, they of the castle conveyed themselves out of a false postern and fled, leaving the castle with only a prisoner in it and of victuals a good quantity. Then the Deputy, with the Marshal, and Lieutenant and Mr. Aggard, took possession of it, and put therein a ward. This day the Earl of Clanrickard, the Earl of Thomond, the Bishop of Clonfert, O Carroll and Mellanlin Moddere O Madden came to the Deputy with their powers.[xvii] My Lord remained there in camp Thursday and Friday. On Friday afternoon, he rode to the castle of Mulbicke, and there left orders for the keeping of the same. Donough O Connor and his confederates were proclaimed traitors.’[xviii]

The Irish annalists record the same taking of the castle at Meelick thus; ‘A hosting was made by the Lord Justice to banish the O Connors from Meelick, after having heard that they were there; and he conveyed and carried great guns to Athlone, and from thence in boats to Meelick, while he himself marched his army through Bealach-an-fhothair (now Ballaghanoher, near Banagher in County Offaly) and by Lurcan-Lusmhaighe. He afterwards took Meelick and Brackloon, and slew Donnchadh, the son of Colla, together with others of the warders.[xix] The entire territory was plundered and ravaged on this occasion. The sons of Melaghlin balbh were banished from the territory, together with the insurgents. The Lord Justice left an English constable at Meelick, i.e. Master Francis, and took hostages from the two O Maddens, from Melaghlin modardha and Breasal, and other hostages from MacCoghlan, namely his son and others; and thus was Siol-Anmchadha taken, and it is not easy to state or enumerate all that was destroyed on that expedition. Three weeks before Lammas that was made.’[xx]

About a year after the taking of Meelick in 1557, after professing his loyalty to the Crown and in consideration of his providing forty fat cows ‘for the victualling of the castle of Mylicke’, Melaghlin modartha was granted by the King ‘the office of captain over all his nation of O Madden’s Country; and the land of O Maddens on either side the Shennyn, except the lands belonging to the castle of Milyke.’[xxi]

The significance of the taking of Meelick

The significance of this event in 1557 lies in the fact that the overthrow of the rebels and the installation of a ward was one of the first tentative steps to the English administration regaining a more or less effective, though at first somewhat intermittent, control over the Manor of Meelick and its river crossings since the mid-fourteenth century. Noticeably, in their appointment of the new chieftain, the English Deputy reserved from his grant of all the traditional O Madden lands only the Manor of Meelick, which is described as belonging specifically to the Queen, and is leased only to those currently loyal to the Crown.[xxii] Only two years later the Earl of Clanricarde was requesting that he be made constable of the castle. While the matter was referred, on the advice of the Queen’s Council, to the Lord Deputy for his consideration, the Earl appears to have been eventually successful, as both he and one of his sons were granted the lease of the manor and castle in joint-tenancy of the Crown in 1570. The extent of the Manor as it stood at the time of the second Earl’s grant differed little from that described in later leases throughout the sixteenth century. Circumscribed within its boundaries were the ‘site of the manor or castle of Milick in the Yellow island on the river Shynnen in Co. Connaghe, another isle near the Yellowe island, the village and land of Myleeke, two other islands pertaining to the castle, and three weirs on the River Shynnen.’

While the detailed description of the Manor’s constituent parts at no time mentions the friary, the friary and what was described as the small island whereon it stood, appears to have been part of a separate leasing arrangement during this period. By 1574 Meelick was one of the many friaries and abbeys acquired by the Earl of Clanricarde, after their suppression by the Crown. The list of abbeys of the barony of Longford (the name given to the English administrative division that equated with the ancestral O Madden lands of Sil Anmchadha) bear witness to the amount of church property acquired by the Clanricarde family in the wake of Crown confiscations and the financial benefits to be derived from professing loyalty to the Crown when it came to the disposal of Church lands. Noticeably, the Clanricardes acquisition of the Church property was not only confined to their own traditional territory but extended deep into Sil Anmchadha. In the then barony of Longford alone, the Earl himself held Meelick friary, Abbeygormacan and the abbey of Portumna while Clonfert abbey was held by the Earls cousin, Roland Burke, Bishop of Clonfert. On the border of O Madden’s Country and O Kelly’s Country the Earl’s brother, Redmond na scuab Burke of Clontuskert held the priory of Clontuskert Ui Maine. As the Clanricardes remained loyal to the Roman Catholic faith, the abbeys and friaries that came under their control received a measure of protection not accorded to all of the foundations acquired by the Crowns supporters.

Donal O Madden, last chieftain of O Madden’s Country

Melaghlin balbh’s fall from grace with the English was short-lived. His alliance with the Dublin administration appears to have been in place as late as 1561, when the Queen commended him for his readiness in her service and required him to assist in the struggle against the Ulster lord, Shane O Neill.

In 1566 Sir Henry Sidney, the then Lord Deputy marched south from Ulster to Roscommon and on to Athlone. There, he recounted later, in addition to many of the O Kelly’s and O Farrells, there came to him ‘the two O Maddyns of both side the Shenen, and submitted themselves and their countrey, with the strong castell of Melike.’[xxiii] It would appear from the Lord Deputy’s account that there was, at that time, again two ruling or rival O Maddens over the territory of Síl Anmchadha.

Both Melaghlin balbh and Melaghlin modartha died in 1566. Melaghlin modartha’s position was taken by Donal O Madden, son of that John slain ten years earlier by Breasal dubh.

With the death of their ally Melaghlin balbh, the Queen’s representatives came to an arrangement with Hugh ( ie. ‘Aedh’), ‘eldest son and heir of Melaghlin Ballagh O Madden, Captain or Chief of his Nation of the Longefort with Silanchia commonly called O Maddens country.’ ‘In consideration of his fathers death and for the good and better government of the said country,’ the Queen recognised Hugh as Captain of his Nation.[xxiv] Hugh, however, was killed in the following year by Donal son of John O Madden in his rise to power. Donal was charged under English law with Hugh’s murder, but was cleared, ‘he having shown by letters of the Bishop of Clonfert and the clergy of the diocese that he was not guilty of the murder.’ After paying a fine of eighty cows to the Lord Deputy, he was recognised as Captain of his Nation in 1567 and again confirmed in that position under letters patent in 1570.[xxv]

While Donal remained generally loyal to the Crown, the principal rebellious powers in Sil Anmchadha by this time were Owen O Madden of Lusmagh and Cobhthach óg (ie. ‘Cogh the younger’) O Madden of Claremadden. The former was a son of Melaghlin balbh and therefore a younger brother of that Hugh O Madden killed by Donal, while Cobhthach óg was apparently the son of that Cobhthach of the Sliocht Breasail killed more than twenty years earlier, in 1547. These two were identified by the English as being in open rebellion and were proclaimed rebels by the Crown. Together with Sir Edmund Butler, they raided continuously along the banks of the Shannon. To restrict these attacks, a Chief Sergeant and Water Bailiff were appointed over the River in 1570.

At the beginning of 1570 Sir Edward Fitton reported to the Lord Deputy that both Owen and Coghe O Madden ‘go about openly.’ The castle of ‘Longhurt’ (ie. Longford), the territory’s principal castle attached to the office of chieftain, had been committed by the Crown’s Council in Ireland to the custody of one Lady Giles and a ward was put therein to maintain it for the government. By February of that year the ward was refusing both Lady Giles or the Council’s representatives access and had instead received Coghe O Madden. Donal O Madden was the focus of attacks from both Owen and Coghe. Owen and other rebels raided Donal and reportedly all of the territory with the exception of Meelick was spoiled, while Coghe raided Donal and brought his prey back to Longford. Donal, however, rescued and recovered his property from Coghe.

O Madden’s territory was also subject to raids from neighbouring lords, with the Earl of Clanricarde raiding deep into Sil Anmchadha in 1570 and despoiling the O Horan lands about Fahy and Meelick, referred to in a contemporary English dispatch as ‘O Horan’s Country’.[xxvi]

Donal, on his confirmation as Captain of his Nation by the Crown in 1570, was described as ‘of Clonfeagh,’ a reference to the castle of Clonfeahan in the parish of Kiltormer. (While the castle at Longford was attached to the office of chieftain, it is unclear whether Clonfeahan was also attached to that office or was the original residence of Donal prior to his assuming that office.) It would appear to be about this time that, with the consent of the Crown, Donal came to occupy the chiefry castle of Longford.

The remains of Longford Castle in the parish of Tiranascragh, from its architectural features the earliest surviving of the castles in the territory of the O Maddens.

The Manor of Meelick and the sons of the Earl

At various times the Manor of Meelick went out of loyalist hands during the rest of the late medieval period, as the loyalty of the Clanricardes wavered and as the rebels fortunes changed. One of the largest obstacles to peace in Connacht was Clanricarde’s own sons Ulick and John Burke, the ‘Mac an Iarlas’ (ie. ‘sons of the Earl’), who fluctuated from fighting among themselves for prominence to rebelling against the anglicisation of their patrimony for much of the 1570s. The situation in Connacht was only exacerbated when their father was taken to Dublin in 1572, there to be held and questioned over his wavering loyalty.

Chaos had spread throughout neighbouring territories, as the Earl’s sons, their allies and their Scots mercenaries traversed Clanricarde and its neighbouring territories, including Sil Anmchadha, plundering the property of those loyal to the Queen. One William O Farrell was constable of the Queen’s castle at Meelick in 1572 and kept the castle from falling to the Earl’s sons, but was reluctant to hold out for much longer. The constable sent his servant, William O Hanen, to Dublin to seek out the Earl and learn his pleasure for the castle. Clanricarde reputedly sent word by O Hanen that ‘it should be delivered to his sons and so it was, and thereupon razed to the ground.’[xxvii]

The Lord Deputy wrote to the Queen in July 1572 requesting ‘speedily eight hundred soldiers’. Meelick castle and Athenry, he reported, were destroyed by the rebels, who were also intent on burning the castle of Ballinasloe, held for the Queen, on the River Suck. Síl Anmchadha was ravaged by the Burke brothers early in their campaign. Meelick castle ‘which was a very fair house situated upon the Shenon, and her Majestys own inheritance, with other buildings thereabout’, lay in ruin for some time after. In September of that year James Fitzmaurice, Ulick Burke, the Earl’s son, with one of the principal Mayo Burkes, and a large rebel force passed over the Shannon with O Madden’s assistance. (The reference to O Madden here is more likely to be a reference to Owen O Madden as opposed to Donal the chieftain) The destruction of property only came to a temporary halt with the eventual release of the Earl in the autumn of that same year, in an attempt to pacify his sons. Fighting, however, would continue intermittently for at least another decade.

The town of Clonfert was also destroyed at this time, as was the market town of Longford, with the exception of the castle, which still remained in Donal O Madden’s hands. Of Meelick and the Franciscan friary, the English reported in 1574, ‘in old time, it was a good market town, and now there remaineth nothing but the abbey and certain other old buildings thereabout, where the town was, and the castle is clean destroyed, the Earl and his son John (one of the destroyers thereof) being joint tenants of the Queens for twenty-one years by indenture.’ Three years later, the ‘frierie of Myleacnascen’ (ie. Meelick, in Irish ‘Milic na Sionna’) was described, in a list of the Queens lands and possessions in Connacht, as lying ‘waste’.[xxviii]

By March of 1574, the number of Scots mercenaries in the country was such that neither the Bishop of Clonfert or Archbishop of Tuam could travel by land to attend a session with Sir Edward Fitton, President of Connacht, at Athlone that month. To attend, they requested a ship be dispatched to collect them at Clonfert.

The Earl’s sons submitted to the Lord Deputy in 1576 and were taken to Dublin as a pledge for the destruction they wrought two years earlier. Once there, however, in breach of the terms of their lax confinement, they availed of an opportunity to escape and returned to their own territory. Not long thereafter, their father the Earl, suspected by some of having been complicit in the escape of his sons and accused of conspiring to recruit Scots mercenaries, was arrested again and taken to Dublin, where he was held prisoner. His territory was left in the hands of English captains and constables. Fighting resumed, and in the summer of that year, the Mac an Iarlas burned the town of Athenry. By the following year peace had been established between the English and the Earl’s sons, although the Earl still languished in prison. In 1578 the Earl was taken to London and there he remained in custody until the eve of his death.

By 1580 the Mac an Iarlas were fighting among themselves and at peace with the English. John Burke, however, enticed his half-brother, Ulick, to renounce the English cause he now advocated, and, in return, John promised to return his son, whom he had taken prisoner, and give up to Ulick certain lands that he held. On reaching an agreement, the brothers, of one accord, rose up against the English. They traversed south east Galway, first demolishing ‘the white castles of Clanricarde’, the castle of Loughrea, and ‘scarcely scarcely left a castle from Clonfert-Brendan in the east of the territory of Sil Anmchadha’ to Kilmacduagh, and from Uaran in Roscommon to Clondegoffe on Lough Derg, which they did not demolish. Their campaign engulfed many of the dissidents of the neighbouring territories and ‘in short, the greater part of the people of Connacht joined in this war.’[xxix]

Meelick castle was, by 1580, in ruins and out of the Queen’s control, and providing a mid way point on the Shannon, between Athlone and Limerick, where rebels were stopping and receiving relief, ‘all of the passengers finding great ease and commodity by it.’[xxx] The governor of the province Sir Nicholas Malbie requested that same year that the Queen ‘grant me the same place in free socage to me and my heirs, or else for one hundred years, at the accustomed rent. I will build up the castle and keep residence there.’ In an effort to restrain the kern on the river, it was decided that a continual ward be appointed at Meelick, ‘to stop the passage of undutiful people.’[xxxi]

Finally, in the summer of 1581, after a vigorous English campaign that saw the execution of some of their relatives and the demolition of their towns, the Mac an Iarlas were reconciled to the Crown. In October, Donal O Madden, with many of the Connacht chieftains, repaired to the Governor’s house in Galway, there to ‘make a plat for continuing the quietness.’

In 1582 Richard 2nd Earl of Clanricard died and both of his surviving sons, Ulick and John, vied for the succession to the earldom before the English administration. ‘Peace was established, on that occasion, to wit, Ulick to be lord and Earl, in the place of his father, and the barony of Leitrim (in southeast Galway) to be given to John. Their other lands, towns and church livings were accordingly divided between them, so that they were publicly at peace but privately at strife.’ Within a year the third Earl of Clanricard, to consolidate his position, had his uncle Redmond na scuab Burke of Clontuskert and Bishop Roland Burke’s illegitimate son Redmond invite his brother John to a meeting with them, where he and a number of his associates were fallen upon and murdered by the Earl.

With a peace settlement agreed between the Mac an Iarlas in Clanricard and the Scottish mercenaries and the Mayo Burkes rebuffed in North Connacht, the English, through Malbie’s son-in-law Captain Anthony Brabazon, installed wards in Meelick and in Athenry.[xxxii]

The Composition of Connacht and O Madden’s barony of Longford

To finance their administration and military presence in Connacht, the Government resolved that a rent be agreed and charged from each division of land in the province. The rent would be payable to the crown, and called the Composition rent, after an agreement drawn up in 1585, between the Queen’s servants and the Connacht chieftains; the Composition of Connacht. Up to this time the established practice by which the Crown supported troops in a district was by ‘cessing’, the quartering out of soldiers in the households of the territory in which they were serving. The funds provided by the Composition rents financed the troops and an annual rental charge and taxes effectively did away with cessing and the Gaelic chieftains traditional exactions and dues, known as Coyne and Livery. By signing up to the Composition document, the signatories agreed ‘that all rules and Iurisdicions heretofore used within the said Barrony of Longford, together with all eleccions and customary divisions of lands occasioning great contencion amongst them, shall henceforth be utterly obolished renounced and put back for ever.’ They acknowledged their lands as private property, held under English law, in return for the agreed rent and on condition that they provide an agreed number of soldiers to support the administration when required. In so doing the signatories repudiated the Gaelic legal system in favour of that of England.

Under the 1585 Composition of Connacht agreement, the various lords finally agreed to hold their lands as loyal tenants of the Crown and to abide by the English legal system. They acknowledged their lands as private property, held under English law, in return for the agreed rent and on condition that they provide an agreed number of soldiers to support the administration when required. The Indenture of the barony of Longford, the legal contract executed to facilitate the implementation of the Composition arrangement, determined the Queen to be possessed of twelve quarters of land in Síl Anmchadha. These included the four quarters of the Manor of Meelick, attached to Meelick castle.[xxxiii]

By 1587 one John More or Moore, descended from an old Anglo-Norman family of Barmeath in County Louth and active in the Elizabethan administration in Connacht was tenant at Meelick castle.[xxxiv] In the early 1580s he served among the horsemen of Sir Nicholas Malbie, Lord President of Connacht, and acquired lands in Roscommon. In 1581 he was appointed to the office of Clerk of the pleas of the Crown in the Province of Connacht and Thomond, an office he held until at least 1596. In the 1585 Composition of Connacht he was described as seated at Cloonbigny in the County Roscommon parish of Taughmaconnell. More married Lady Mary Burke, daughter of Richard 2nd Earl of Clanricarde and by the early seventeenth century held the castle of Meelick for the Earl of Clanricarde. Intimately connected with the politics of that lordship, More would go on to found a family that would, like the O Maddens and Clanricardes, be inextricably linked with the eastern region of County Galway.

The New English

A small number of new settler families, other than the Mores, for the most part those who came as part of the new Tudor administration, established themselves in O Madden’s country during the late sixteenth century. These men became collectively known as the ‘Nua Ghaill’ or ‘New English’, to distinguish them from those families of Anglo-Norman descent settled in Ireland since the twelfth century, such as the Burkes, Butlers or Fitzgeralds, who became identified as the ‘Sean Ghaill’ or ‘Old English.’ The ‘Nua Ghaill’ chose to remain in the country and acquire property whereon to settle, rather than return to England or seek further military service on the Continent. Several married the daughters of local landed magnates or acquired lands confiscated by the Crown from rebels and, by the beginning of the following century, had established families that acquired social status on a par with the more prominent of the local landholding class. Their names such as Lawrence, Brabazon and Mostian, though alien to the late medieval Gaelic landscape of Sil Anmchadha, belied one important common denominator with the native landholding families that would prove important for their future assimilation into the territory, their common Roman Catholic faith.

The sixteenth century was one of dramatic political change in Ireland. At it’s beginning, Ireland was a part of a widespread Gaelic world on the western edge of Europe, sharing a similar language, heritage and alliances with the lords of the Scottish Highlands. The close of the sixteenth century saw the monarchies grip on Ireland tighter than ever. The Reformation had failed to make significant inroads among the Irish or Anglo-Irish, but Native culture was under severe threat from the process of anglicisation. Connacht now had an effective English Provincial administration, with its own President since 1570, and the lords of the province had signed up to an agreement holding their lands from the Crowns hands. The last of the Tudor monarchs was on the verge of completing the conquest of Ireland. Ulster was one of the last obstacles to the anglicisation of a politically Gaelic Ireland. That provinces fastnesses and inaccessibility prevented the Government from exercising effective control over the entire island. Ulster, and in particular the lordships of the O Neills and the O Donnells, would have to submit to the Tudor designs before this could be accomplished.

The Nine Years War and the territory of the O Maddens

Having set upon the policy of settling Ulster with new colonists, the English government decided that the O Neill lordship would be carved up and part of it given to one Hugh O Neill, a claimant to the earldom of Tyrone, regarded as one who would act as puppet Earl for the administration. Once established with government help, however, O Neill, now Earl of Tyrone, saw the largest threat to the lordship not as his own internal rivals, but the new English settlers. Turning against the crown, O Neill began to bring the entire lordship under his control and sought to expel the English officials. War broke out between O Neill and the Crown. With O Neill initially successful, many of the disenchanted Irish chiefs and lords gathered to the banner of O Neill and that of his ally already in the field, Red Hugh O Donnell. O Neill, inspired by local power politics in the beginning, would in time come to be regarded as the great champion of the counter-Reformation in Ireland and a real threat to the Queens authority. The conflict spread throughout the kingdom of Ireland and so began the Nine Years War.

Many of the O Maddens joined O Donnell in the rebellion, with the exception of their chieftain Donall, his son Anmchadh (ie. Ambrose) and their supporters. Foremost among the rebels of Sil Anmchadha, which included several senior members of Donal of Longford’s extended family group, was Owen O Madden of Lusmagh.

A party of dissident O Maddens led principally by Owen of Lusmagh, with several of the disaffected Burkes, Clanricards cousins, with their Scots mercenaries, were reported in 1595 to be ‘lying lurking…in O Madden’s country, to enter and spoil MacCoghlans country, together with the Kings and Queens counties and so to have joined with Feagh McHugh O Byrne’ a principal Wicklow rebel.[xxxv] Prior to the rebels crossing the river into the east, the Gaelic sources report that the raiders attacked and destroyed Meelick castle, Tir Athain and most of the ‘bailes’ (urmhór bhailtedh) of Síl Anmchadha, with the exception of Longford.[xxxvi] In addition they plundered and destroyed the nearby town of Clonfert-Brendan and took the Protestant Bishop Kirwan prisoner. A contemporary English report, from February of that year, attributed much of the damage done principally to the sons of Redmond na scuab Burke of Clontuskert, describing their spoilation of Clontuskert, ‘Ballanavan’ and the Castle and town of Meelecke in O Maddens Country.’[xxxvii]

On MacCoghlan’s information, the Lord Deputy made for the Shannon and on his arrival found many of MacCoghlan’s towns destroyed. Surprising the rebels, the English, with MacCoghlan’s aid, killed seven or eight score, ‘among whom were the leaders of the Scots and of the best of the rebels the O Maddens.’[xxxviii] ‘The rest got over the Shannon by flight and returned again into Connaght; saving some five or six and forty which were gotten into the castle of Cloghan, being the principal castle of importance in O Maddens country.’[xxxix]

The taking of Owen O Madden’s Cloghan Castle 1595

While it has been suggested that the O Madden referred to as being at the head of the party was Donal of Longford, the particular O Madden mentioned in contemporary English dispatches was Owen mac Melaghlin balbh whose residence they confirm Cloghan was.[xl] Those who surrounded the castle were under the immediate command of the Lord Deputy Sir William Russell. O Madden, being absent on the occasion, ‘had left a ward of his principal men in his Castle, where assoone as they perceaved my Lord approach neare, they sett three of their houses on fire, wch were adioyning to the castle, made shott at us out of the castle, wch hurt two of our souldiers and a boye.’ When asked to surrender the occupants refused, declaring to the Lord Deputys man, Captain Thomas Lea, that if all that came in the Deputies company were themselves Lord Deputies they would still not yield ‘but would trust to the strength of their castle and hoped by to morrowe that time that the Deputie and his Companie should stand in as great force as they then were, in expectinge, as it should seeme, some ayde to relieve them.’ A close watch was kept on the castle overnight, entrusted to one Captain Izod, for fear that the occupants would attempt to escape by way of ‘a mayne bogg (that) was adioyning thereunto’. (A large bog lay to the immediate north-west of the castle between Cloghan and its direct access to the Shannon and the main river pass at Meelick, while to the south of the castle and across the Little Brosna River, lay a larger bog but in Tipperary.) That night, on visiting the watch at midnight, ‘and understanding of some women to be within the Castle, sent to them again’ and offered to allow their women flee in advance of the next days assault, but the offer was declined. The following day, one of the English soldiers in Sir William Clarkes Company succeeded in throwing a firebrand up onto the castle’s thatched roof. As the roof took fire, ‘th’alarum was stroke upp, and whilst our shott plaied at their spike holes, a fire was made to the grate and doore, wch smothered manie of them, and wth all the souldiers made a breach in the wall and entered the castle, and tooke manie of them alive, most of wch were cast over the walles, and soe executed. And soe the whole number wch were burnd and kild in the Castle were fortie sixe persons, besides two women and a boye, wch were saved by my Lords appointment.’

Among the names of ‘such chiefe men as were kilde in the Castle of Cloghan O Madden, at ye winninge thereof, which were principall fightinge men, the xiith of March 1595,’ were ‘Shane mcBrasill O Madden of Corglogher, gent., Cahill mcShane O Madden of Kineghan, gent., Donnogh and Owen mc Shane O Madden of Tomhaligh, gents., Molaghlin Duffe mcColeghan of Ballymccoleghan, gent., Captain of shott, and his two sons,’ and several others, including men from O Rourkes country.[xli] Anmchadh mac Mhaoilsheachlin modartha of Clare Madden was among the chief men killed in the fighting the day before the castle was taken. Killed with him also on that day were Coheghe (Cobhthach) oge O Madden and Leve O Madden, both of Claremadden, all three described as three landed men.[xlii] Leve O Connor, of County Sligo, ‘a chief gentleman and a leader of shott and Scotts’ was also killed that day and buried at Meelick. ‘The whole number killed and drown’d (besides those of the castle) were seaven score and upwards, besides some hurt, wch escaped, beinge unarmed, and fled away in great amasement.’[xliii]

Although the rebel O Maddens lost two of their leaders in Cobhthach óg and Anmchadh of Claremadden, Owen O Madden of Lusmagh escaped the loss at Cloghan, but was killed in action in early 1599. Four of his sons, however, were still in the field in rebellion in April of 1599 at the head of fifty foot.[xliv] The sons of Redmond na scuab and the greater part of their people, the Gaelic sources recorded, effected their escape from the forces that took Cloghan Castle in 1595 and were also still in the field in rebellion in 1599 with three hundred foot.

During this period, the 3rd Earl of Clanricard held the lease on the manor and castle of Meelick, and the castle itself was held for the Earl by his brother-in-law, John More or Moore. John Moore’s loyalty appears to have been in question for a time, as he and his wife Lady Mary, harboured at Meelick in 1599 Hugh O Neill’s ally and the Earls implacable enemy, Redmond Burke, Baron of Leitrim, the Earls own nephew and son of the Earls murdered half-brother. Redmond and his troops were retreating before the Earls forces and withdrew into Sil Anmchadha and towards Meelick, where they found temporary refuge facilitated by the Moores. In a letter sent in August of that year to the Lord Deputy Essex from his castle of Leitrim, the Earl described his having pursued them to Meelick ‘to the fort, which was fortified by them on the Shannon, in an island, which ten men might keep against a thousand. And upon my coming, my son, (ie. Richard, Baron of Dunkellin, later fourth Earl of Clanricarde) with certain of our companies, entered into the island in cots and, upon his entrance where the fort stood, the ward, with the rest of the traitors which fled thither for refuge when they were broken, made all the shift they could to fly away, as well in their cots as by swimming, having left a prey behind them in the island. And certain of themselves lost, and the fort destroyed by us, understanding that the said Redmond and his men were fostered at Mylycke by a base sister of mine, which is married to one John More, my son has dispossessed him of the house and left a ward therein, being the fittest place of service betwixt Athlone and the city of Limerick upon the Shannon, and one of the principallest places in this province to annoy Her Majestys subjects, if it were left for want of looking to it. If it had come to the enemies hands, it would be hard to recover it, …and in my opinion is most necessary to be kept for Her Majestys service, during the wars for the safety of this province.’[xlv]

The report that the fort was destroyed but a ward put in the house of Meelick would suggest that these were two separate and distinct entities. This fort is in all likelihood a reference to fortifications erected on the island of Gutáile, straddling the river crossing in front of the castle site. Although the Earl removed Moore as ward, the Moores appear to have regained their position at Meelick some time after.

In 1601 4000 Spanish troops landed in Kinsale, Co Cork, sent by the Catholic King Philip of Spain to reinforce O Neill in his struggle. The defeat at Kinsale of O Neill and O Donnell signalled the effective end of the nine years war. O Neill was forced to retreat northwards, while Red Hugh O Donnell sailed for Spain, to seek further aid of the Spanish king.[xlvi] On receiving word of O Donnell’s death on the Continent, O Neill accepted peace term offered by the Crown and the war ended with O Neills surrender at Mellifont in 1603.

The Flight of the Earls

King James I, of the Scottish Royal House of Stuart, succeeded Elizabeth, and prejudiced by the involvement of Roman Catholics in the recent wars, viewed them as a potential focus for further agitation. He took an even less tolerant stance towards those landowners and their religion than did his predecessor in the early years of his reign. Colonisation plans for Ulster, much of Connacht and areas of Munster and Leinster were planned and set in motion. O Neill was summoned before the new King, but, believing that he would be charged on his arrival in London with plotting another rising, he, his immediate family to hand and his young ally Rory O Donnell took the authorities by surprise and sailed into exile on the Continent. There they hoped to find succour and support at the Spanish Court for a new insurrection. On the Earl’s flight, which saw them eventually find their final resting place in Rome, the Crown confiscated their lands and Ulster was planted with Scottish and English settlers.

While the Ulster Earls would prove a constant threat to the Kings authority in Ireland while harboured abroad, international politics and a new peace treaty between Spain and England would prevent any further aid from Spain or any realistic chance of another rising in Ireland.

Continued at ‘Seventeenth Century.’

[i] Edmund Spenser, ‘A veue of the present state of Ireland’, 1596.

[ii] O Donovan, J., Tribes and Customs of Hy Many. This townland was described as the 2 quarters of Carrowcloghy Tullaghanelicky als Ballyeghnagh circa 1641. Also Cal. Pat. Rolls 16 Jas. I, p.414.

[iii] A great war broke out in Clanricard for control of the lordship on the death of Ulick na gCeann. Ulick son of Richard Og Burke was proclaimed MacWilliam in opposition to Ulick na gCeann’s brother Thomas farranta ‘the athletic’ Burke and held on to power until Richard sassanach came of age. Thomas farranta was later killed by a gunshot in 1545 by the people of Melaghlin balbh O Madden at the pass of Tire-Ithain in Sil Anmchadha as he attempted to flee after a raid he had made into O Maddens country. (AFM)(L.Cé)

[iv] ‘Fear caoin crodha, ceannsa ceart-brethach’ (A.F.M.). O Donovan gives Breasal as the son of John Ó Madadhain and a grandson of Murchadh reagh, chieftain of Sil Anmchadha who died in 1475.

[v] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 57-61.

[vi] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 70.

[vii] Power, G., (W. Brabazon, G. Aylmer, J. Alen), The Viceroy and his critics: Leonard Grey’s journey through the west of Ireland June-July 1538, JGAHS, Vol. LX, 2008, pp. 78-87. ‘The confession of the Viscount Gormanstowne, oon of the Kings most honourable counsaile, John Darsey and William Brymigham, esquires, concerning theffects and proceedings of this my lord deputies jo’nay into Monister Thomond and Conaghte &c.’

[viii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 57-61.

[ix] Cal. Carew Mss. 1, 1515-1574. The indenture between the King and Maleghlen O Madyn saw Maleghlen agree to pay yearly 12d Irish out of every ploughland, while that between the King and Hugh O Maden saw Hugh agreeing to pay yearly 8d sterling out of every ‘carue’ (carucate) of land. Both O Maddens had ‘to find during a fortnight 80 gallowglass’ each. This indenture is recorded with a number of other ‘treaties with the Irishry’ in 1540. (Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 171.)

[x] The appellation ‘Sliocht Breasail’ (A.F.M.) to the descendents of Breasal, who were in opposition to Maoilsheachlainn gott, would imply that the O Madden of 1539 was not descended from this Breasal.

[xi] In 1539, the sons of the Ó Madadhain killed Feidhlim MacCochlain at Banagher, after Sunday mass. As one of those sons responsible for the death of MacCochlain was one Maoilsheachlainn gott, a vigorous opponent of Maoilsheachlainn macBreasail, he would appear to have been the son of Hugh Ó Madadhain.

[xii] The Annals of the Four Masters refer to a son of this Melaghlin balbh in 1595 as ‘Eoghan dubh mac Mhaoileachlainn Bailbh Uí Madagain ó thuaith Lusmaighi.’

[xiii] Cal. of State Papers, 15 Sept. 1548 Richard Baron of Delvin and Sir William Brabazon to Lord Deputy.

[xiv] Melaghlin balbh had at least three sons, Hugh, later Captain of his Nation, Owen of Lusmagh and Coghe who was pardoned in 1550.

[xv] Only later was Kings County extended west towards the Shannon, to include MacCoughlans territory of Delvin macCoghlan.

[xvi] Brewer, J.S. and Bullen, W. (ed.), Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, 1515-1574, First published on behalf of P.R.O., London, 1867, pp. 265-7. The small tower house referred to as set alight by its occupants was Illanedarragh, also known as Caisleán na darach. The castle stood on a small island opposite the townland of Keeloge called Oileán na darach, to guard the narrow pass on the river north of Meelick castle. The Shannon could be crossed at this upper pass by way of shallow waters between the eastern River bank and the large island of Incherky. From there the western bank at Keeloge could be reached by way of Oileán an darach. Still standing in the late seventeenth century, no part of this castle would remain by the early nineteenth century. The island later came to be known as Old Castle Island.

[xvii] The Earl of Clanricarde, giving an account in 1578 of his various services to the Crown down the years, mentioned his attendance on the Lord Deputy at the taking of Meelick. ‘Item: the Earl of Sussex, being Lord Deputy, pursued the Conors and finding the castle of Meelick to be a refuge for the said Conors, camped about the said castle and took it; at which time I was with his Lordship, six score horsemen, 320 galloglasses, six score shots, with a number of kearns well appointed, if his Lordship had had need of my service.’ (H.C. Hamilton (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reign of Elizabeth, 1574-1585, London, Longman, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1867, Preface, pp. xlvii-liii.)

[xviii] Cal. of Carew Mss. 1601-03.

[xix] Donnchadh mac Colla (Donogh mcCollo O Madden) appears to have been warder at Brackloon as opposed to Meelick, as the English account does not refer to any noteworthy casualties at Meelick. Brackloon was held twenty-eight years later by Ruaidhrí bán mac Colla Ó Madadhain (ie. Rory bane mcCollo O Madden.)

[xx] Annals of the Four Masters.

[xxi] Morrin, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Patent and Close Rolls of Chancery of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, Vol. I, Dublin, Alex, Thom & sons, 1861, I Eliz. I, January, p.415.

[xxii] About a year after the taking of Meelick in 1557, after professing his loyalty to the Crown and in return for providing forty fat cows ‘for the victualling of the castle of Mylicke’, Melaghlin modartha O Madden was granted by the King ‘the office of captain over all his nation of O Maddens country; and the land of O Maddens on either side the Shennyn, except the lands belonging to the castle of Milyke. (Fiants Eliz.1, 1558-9)

[xxiii] Sidney, H., Sir Henry Sidney’s Memoir of his government of Ireland 1583, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, First series, Vol. III, 1855, p. 40.

[xxiv] 8th Eliz and J.G.A.H.S. Vol. II, pp 21-33 1902, In return, Hugh was to pay ‘100 beeves and fat cows at or before the Feast of All Saints, to furnish 80 galloglasses for four weeks annually, to find 8 armed horsemen and 24 foot-soldiers for 40 days at the Royal hosting, and to pay annually twelve pence for every carucate of land within the said country.’

[xxv] Fiants, Eliz. I 1567.

[xxvi] The O Horan’s patrimony appear to have been combined as one parish, referred to as Muintirhoran or Muintir Uí hOdhrain, in the sixteenth century. The parish of Muintir Uí hOdhrain comprised seven quarters of land at the composition of Connacht fifteen years later. Both Meelick and Fahy were also administered by one parish priest in the early eighteenth century and this appears to have been the case up to the early nineteenth century.

[xxvii] Cal. State papers 1571-75 ed. by M. O Dowd. (refer to ‘2nd Earl of Clanricarde’ under ‘Families.’)

[xxviii] J.G.A.H.S. Vol. 33, ‘a list of the monasteries of Connacht 1577’. Although waste, the friary was valued at 10s.

[xxix] Annals of the Four Masters.

[xxx] Cal. of State Papers 31 July 1580.

[xxxi] Cal. of State Papers 31 July 1580.

[xxxii] Cal. of State Papers 29 May 1582 Sir Nicholas Malbie to Walsyngham.

[xxxiii] The lease of the Manor extended to the second Earl of Clanricard and his son John ‘mac an Iarla’ in 1570, at a rent of £3 6s 8d and for the maintenance of one horseman, was given for a period of twenty one years, with the proviso ‘if the lessees so long live.’ The Crown, however, transferred the lease of Meelick Manor to a number of different individuals long before that initial period elapsed. One John Vause or Vawce, gent., was granted the lease about 1576 and Nicholas Ailmer of Dullardstown, gent., in 1584. Prior to April 1587 Sir Edward Waterhous gave the lease to one Thomas Dillon for 225l and in 1590 Richard Power, son and heir of Lord Poer, was granted the lease of the Manor. In all cases the extent of the manor remained unchanged.

[xxxiv] He was resident at Meelick since at least 1587, in which year he took legal action against Roland Lynch, Protestant Bishop of Kilmacduagh, over title to the demesne lands of Kilmacduagh. That legal action resulted in success for the same More of Meelick in 1610. The Regal Visitation of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh 1615, Rev. P.K. Egan, J.G.A.H.S. vol. 35, 1976.

[xxxv] Cal. State papers, Eliz I 1592-1596, 1890 pp 489-491. The sons of Redmond na scuab Burke. Redmond, described as ‘of Clontuskert’ in 1574 and again when pardoned in 1581, died in 1595. Clontuskert was likewise spoiled by the Burkes, as was Ballanavan or Ballyneren (Ballyneren was part of the estate of Domhnall of Longford in 1585) in 1595, Vol clxxxvi, Cal. State papers 1595-6.

[xxxvi] Annals of the Four Masters. The translation rendering Meelick as ‘O Maddens mansion seat’ is incorrect. The actual wording is Meelick O Madden, from ‘& co ro brisedh, Míliuc Uí Madaccáin, Tír Athain, & urmhór bhailtedh na tíre leó cenmota an Longport.’

[xxxvii] The sons of Redmond na scuab Burke. Redmond, described as ‘of Clontuskert’ in 1574 and again when pardoned in 1581, died in 1595. Clontuskert was likewise spoiled by the Burkes, as was Ballanavan or Ballyneren (Ballyneren was part of the estate of Domhnall of Longford in 1585) in 1595, Vol clxxxvi, Cal. State papers 1595-6.

[xxxviii] Cal. State Papers, Eliz I 1592-1596, 1890, pp. 499-500. Mr John Lye to Sir Geoff Fenton. ‘from the defaced castle of Cloghran in Losmagh’ 1595-6 March 13.

[xxxix] Cal. State papers, Eliz I 1592-1596, 1890, pp. 489-91.

[xl] Cal. State papers, Eliz I 1592-1596, 1890, pp. 489-91, p. 500. Donal’s son Anmchadh was so far from being considered a rebel at this time that, one year later Captain Anthony Brabazon could describe him, with one Conner O Kelly, as being ‘taken for perfect good subjects’, and advised that they should be relied upon as the new O Kelly, Ferdoragh, was enticing the sons of John ‘mac an Iarla’ Burke to take Meelick castle. Cal. State Papers, Eliz. I, 1592-1596, 1890 (May 6 1596).

[xli] Cahill mcShane O Madden of Kineghan, gentleman is identified in his pardon of 1586 as ‘Cale mcShane mcFarre’ of Kenechan. (Fiants, Eliz. I) Donell mcShane of Kynneghen, evidently his brother, was pardoned in 1585, and both appear to have been nephews of Brasil mcFerriagh mcDonogh of Lismore. Keenaghan, Lismore and Ballynakill were treated jointly as comprising of five quarters in the Indenture of the barony in 1585.

Tomhaligh is more correctly Tomsallagh in the parish of Kilquain. ‘Donogho mcShane mcEdde of Tomhallogh’ received a pardon alongside Owen of Lusmagh and ‘Donell mcShane of Kynneghen’, among others, in 1585 (Fiants, Eliz. I).

[xlii] The Annals of the Four Masters refer to Coheghe oge as Cobhthach son of Cobhtach Ó Madadhain. He would appear to be the son of that Cobhthach killed in 1547 by the people of Maoilsheachlainn balbh and therefore a cousin of Anmchadh mac Mhaoilsheachlainn modartha. Leve O madden is possibly Amhlaibh or Awly O Madden.

[xliii] O Donovan, J., ‘The tribes and customs of Hy Many, pp 149-151.

[xliv] Cal. Carew Mss. 3, 1589-1600, p. 300 ‘A general computation of the Irish forces in rebellion when the Earl of Essex arrived in Ireland.’

[xlv] Cal. State Papers 1598-99, 1895, p. 137. The report that the fort was destroyed but a ward put in the house of Meelick would suggest that these may have been two separate and distinct entities.

[xlvi] With Red Hugh O Donnell sailed Redmond Burke, Baron of Leitrim in east Galway, who would apply for entry to a Dominican friary at Lisbon.