It seems only fitting that when a man’s severed head is re-attached to his body and he is thereupon returned to life, the occasion should be marked in some small way.

In the case of Cairbre Crom, the reputed sixth century ancestor of the O Kellys, Maddens, Egans, Kennys, Treacys, Larkins and many of the Gaelic families of east Galway and south Roscommon, this was done by erecting a cross to mark the spot.

The late fourteenth century Irish manuscript called the ‘Book of Hy Many’ recounts that Cairbre was for nine years chieftain or king of Uí Maine, a wide area which at that time covered a large part of eastern and central Galway and southern Roscommon. About the beginning of autumn, after a particularly busy day ‘plundering and devastating’ he and his twenty-seven companions rested and slept at a place called Derryconny. There he was attacked and killed. His head was severed from his body and taken to the ‘tochar’ (a timber causeway across a bog) of Cloonburren and ‘left on a green flagstone in the middle of the tochar.’

St. Ciaran, on hearing word that Cairbre had been killed set out from his nearby religious settlement at Clonmacnoise and made his way west across the River Shannon with some of his fellow clergy to ‘Turloch Droma,’ carrying with them their bells. On reaching the body they rang their bells round the headless body and from that ceremony the place derived it’s future name ‘Ard na gclog’ or ‘the height of the bells.’

Taking the body with them they then proceeded to the spot on the bog path where the head lay, only to discover a demon keeping company with the head. St. Ciaran demanded the demon account for his presence to which he replied that the previous owner of the head had been a faithful servant of his and on that account he was keeping and accompanying the head. The saint challenged the demon and deprived him of Cairbre’s head, claiming that Cairbre, before his death, had submitted to the Christian saint and confessed his sins before God.

The meeting of St. Ciaran and the demon upon the tochar of Cloonburren, by the author.

The religious took leave of the demon, leaving him at the flagstone on the tochar where they had found him. Thereafter it was said that anyone who should tread upon that stone ‘does not do what is to his welfare that day.’

They brought both head and body across the Shannon to Clonmacnoise, placed the head on the body, placed St. Ciaran’s pillow beneath the head, whereupon at the saint’s command the head adhered to the body and Cairbre returned to life. Not everything worked out smoothly as there was a bend in Cairbre’s neck, from which, for the remainder of his life, he was known as Cairbre ‘crom’ or Cairbre ‘the bent’ or ‘stooped.’

Now that is a good story!

I could go on and relate Cairbre’s experience while departed, his soul contended over by angels and demons and the credit he ascribed to his confession and prayers in saving his soul, but that’s for another day. Also for another day, and a more detailed article on the origins of the O Kellys and the wider Uí Maine tribe in the main body of the website, is the story of all the lands in east Galway reputedly bestowed on St. Ciaran’s foundation at Clonmacnoise by Cairbre in return for the miracle and all the lands later bestowed by his descendant Ceallach (from whom the O Kellys are said to derive).

The Cross of Cairbre Crom

A cross was erected which tradition in the mid nineteenth century said marked the spot where St. Ciaran re-united Cairbre Crom’s head with his body. The antiquary John O Donovan stated in 1857 that the cross existed in his day but as modern maps dated 2005 show little evidence of its existence or precise location today, I and my good friend and colleague Richard Campbell, Engineer and Mayo-man now based in Ballinasloe, decided that we would launch a two-man six mile expedition to see if we could locate the remains of the cross.

Supporting references and evidence

Much of the evidence relating to its precise location is derived from the nineteenth century antiquarian John O Donovan and a reference in an old book called ‘The Registry of Clonmacnoise.’

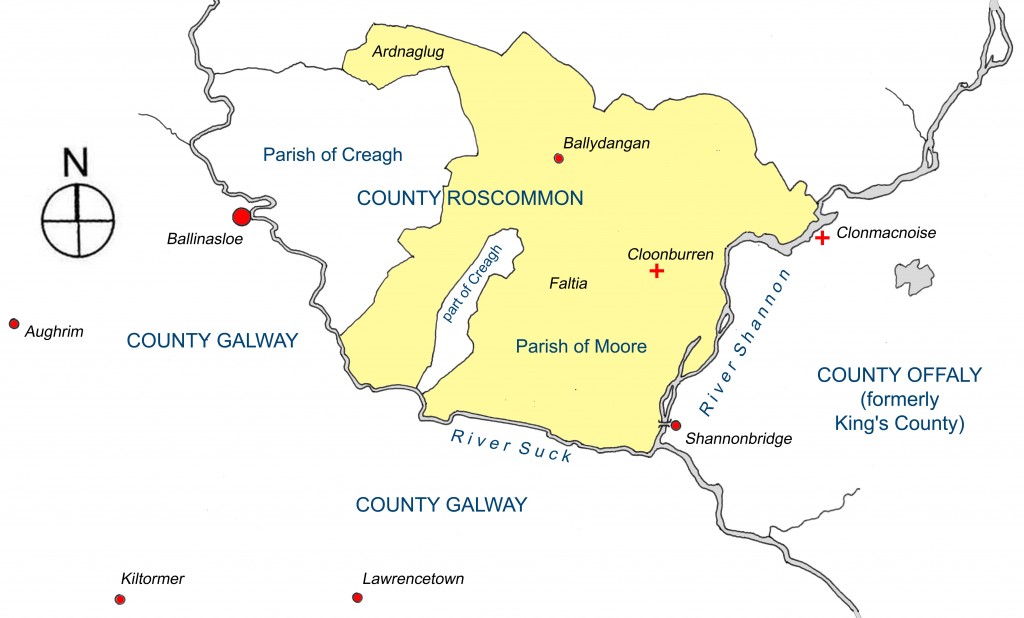

O Donovan described the ‘mutilated’ remains of the cross in the mid nineteenth century as situated ‘near the old church of Cloonburren’ in the south Roscommon parish of Moore, between the town of Ballinasloe on the River Suck and the site of Clonmacnoise on the River Shannon. More specifically he described it as ‘standing almost in the middle of the tochar which leads from the old nunnery of Cloonburren in the parish of Moore to the townland of Faaltia.’ He had visited the site when compiling his ‘Ordnance Survey Letters’ and the site of the old nunnery at Cloonburren, from which he said he had a good view of Clonmacnoise in the distance.

Map showing Cloonburren graveyard and the site of the old nunnery, within the parish of Moore (shown in yellow).

We knew that the cross lay to the east of the modern townland of Faltia, from an account in a seventeenth century translation of the ‘Registry of Clonmacnoise.’ That story related that how a later O Kelly, a descendant of Cairbre Crom, killed a child and when the Church forgave him he bestowed further lands on the foundation at Clonmacnoise. Over time the Church’s interest in these lands was forgotten but when an even later descendant of Cairbre, Lochlann O Kelly (who, depending on which source one reads, flourished about the thirteenth or fourteenth century) disclosed them to the Bishop of Clonmacnoise, he rewarded Lochlann and his descendants with a lease of Church lands, the payment of which was six cows and six fat hogs on the feast of St. Martin and the obligation to repair the tochar or ‘causey (causeway) of Cluyn Buyrynn from the cross of Cairbre Crom westwards to the Cruaidh (‘hard ground’) of Failte.’

In O Donovan’s time the cross had already lost both of its arms and looked more akin to a pillar stone but was still called ‘the Cross of Cairbre Crom’ by the local population, who retained ‘a vivid tradition that it marks the spot where St. Ciaran put on the head of Cairbre Crom, King of Hy Many.’ (The ‘Book of Hy Many’ actually stated that this was the place where ‘they put the head along with the body’ and that Cairbre was not resuscitated until the head was attached to the body at Clonmacnoise).

The last item of information at our disposal was O Donovan’s description of a holy well at the foot of the cross that at one time took it upon itself to remove to the other side of the ‘tochar’ ‘in consequence of an insult offered it by an imprudent woman who washed her clothes in it.’ The holy well, O Donovan reported, had dried up by the time of his visit, ‘as a result of drains sunk on both sides of the causeway to keep it dry.’

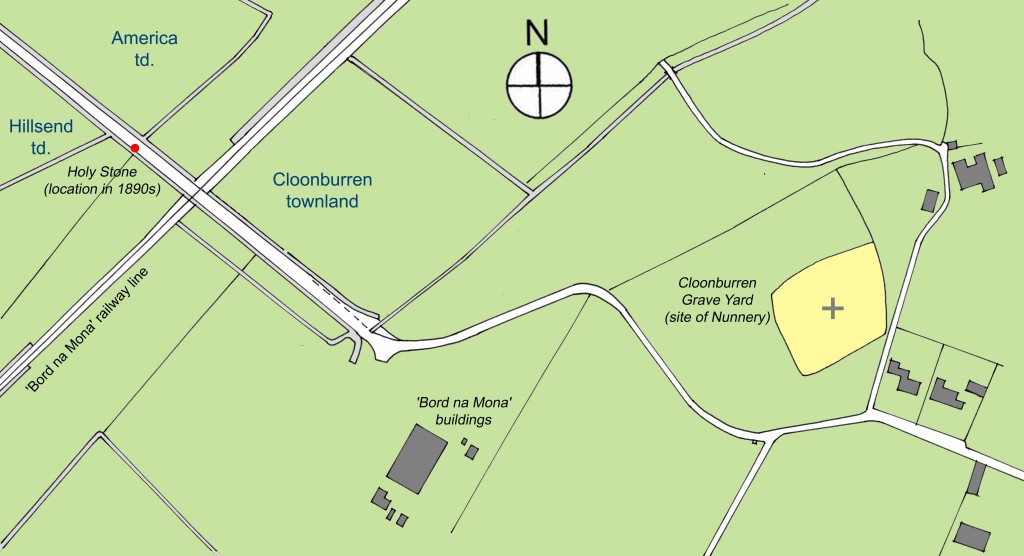

Looking at the Ordnance Survey maps, the ‘old nunnery of Cloonburren’ visited by O Donovan was evidently that site identified on nineteenth century maps as ‘Cloonburren Grave Yard.’ Despite the fact that there was no record of any artefact resembling a cross or pillar-like stone on the mid nineteenth century maps, maps produced later in that century showed a ‘holy stone’ near the site of grave-yard, by the side of the narrow bog road in the townland of Hillsend, between Cloonburren and the townland of Faltia. This, we believed had to be the remains of the stone identified as part of the cross. The presence of a drain running for a short distance on either side of the road in the vicinity of the stone, as described by O Donovan, appeared to confirm its identity. This had to have been the site of Cairbre Crom’s cross, where St. Ciaran and his followers encountered the demon and Cairbre’s head was re-united with his body.

Map showing the position of the ‘holy stone’ (in red) as indicated on the 1890s Ordnance Survey maps, in relation to Cloonburren graveyard (in yellow) and to surrounding early twenty-first century features and buildings.

The intrepid Explorers

So earlier today, armed with these details, little map evidence, a copious amount of curiosity and a stern warning from Alison not to stand on any cursed flagstones, we boldly set out from the town of Ballinasloe to cross the river Suck and travel the six miles or so to explore the lower regions of County Roscommon in search of the remains of Cairbre’s cross.

The area over which these events were claimed to have taken place is still identifiable in the modern placenames within the parish of Moore. Ard na gClog, where the monks rang their bells about Cairbre’s headless body, is today the townland of Ardnaglug, much of it bogland in the parish of Moore and the memory of the tochar, the path over the bog, is still continued in the name of local townlands such as ‘Cappantoghar’ (the tillage plot of the tochar).

As we drew near the graveyard of Cloonburren, down narrow country roads, the topography of the area clearly matched the ancient legend. All about was bogland, much of it in use by the Semi-State body ‘Bord na Móna’ charged with the harvesting of peat from the bog for the production of fuel, with areas of grassy high ground and agricultural land.

Cloonburren graveyard, the site of the early Christian nunnery or convent, said to have been founded in the sixth century by the Virgin Saint Cairech Dairgean who died in 577, sister of St. Eanna of Aran. Within the graveyard lie the remains of several early Christian graveslabs bearing incised crosses.

The views over the surrounding bogs to the north from the height of Cloonburren graveyard.

We had the remarkable good fortune of asking directions from a local lady who pointed us in the direction of the graveyard at Cloonburren, only just around the corner. To our surprise, when I asked her if she knew of an historic stone by the side of the road in the area, she did. Not only that, but she informed us that the stone had been struck a number of years ago by a vehicle and knocked into the drain, where it had lain for some time out of view. The same stone had only been removed from the drain within the last two months or so and re-positioned.

We found the stone exactly as she described it and along the same stretch of roadside in the approximate position indicated on the 1890s O.S. map. On either side of the road lay the deep bog drains mentioned by O Donovan in the mid nineteenth century. Here, still standing by the narrow bog road after centuries, was what was said to have been the remains of the Cross of Cairbre Crom, set now in a small base of concrete.

The scarred and damaged stone with a raised and partially rounded central section upon which another element may have stood. Octagonal on plan, this remaining section may have formed part of the upper section of the shaft. No surviving stone base was evident on site. The shape would appear to suggest a possible late medieval or early modern (ie. 1600s) date and a basic structure possibly not dissimilar to a number of late wayside crosses such as the seventeenth century cross found at Kilconnell in east Galway.

The position of the stone as it stands today appears to be approximately 7.75 metres (to the north-west) from its position indicated on the 1890s Ordnance Survey maps. Its position on the 1890s map, on the boundary of three townlands, suggests that the cross may have also served as a ‘marker’ of those boundaries. Richard marks the position of the stone as indicated on the nineteenth century map in relation to the current location of the stone re-positioned earlier this year. The approximate line of the ancient tochar, now a tarmacadamed public road, across the bog to the ‘hard ground’ of Faltia in the background.

We hadn’t expected to find any remnant of the stone standing. Had we arrived three or four months earlier we would not have seen anything. It would have lain in the black water of the drain beneath a thick and impenetrable green blanket of algae. Had we not enquired for directions of a local lady out walking we would not have known of its recent history and repositioning.

In taking it upon themselves to rescue the stone, the members of the local community who did so have not only salvaged part of an ancient monument but a real and tangible link into the dim past of Irish myth and history with the semi-historical ancestor of so many of the Gaelic families of east Galway and south Roscommon.

And it’s only now, as I sit down to write this, that I realise how satisfying it is to think that our journey today adds in some small way to the previous accounts of the centuries old story of the head and cross of Cairbre Crom.

The author with Dennis, Mary and young Donnach Whyte of Cloonburren, whose family lands lie about the graveyard at Cloonburren.

Comments are closed.