© Donal G. Burke 2013

At the beginning of the sixteenth century only a small area about Dublin, known as the Pale, was effectively under English law. Elsewhere, Gaelic law and customs prevailed in varying degrees. Even in a lordship ruled by those of Anglo-Norman descent, such as Clanricarde, Gaelic law was adhered to. The country was divided into a myriad of lordships, many hostile to their neighbouring territories and bound to others in various alliances, with little or no reference to the Crown or a central government.

The submission or adherence of the Burke chieftain of Clanricarde to the king would prove important for the Crown, as his territory was extensive and if he and his successors were to remain loyal, they would provide the English administration, only beginning to establish a significant presence west of the Shannon, with a valuable ally in Connacht.

Clanricarde, as a geographical area, covered a large portion of what would later be the county of Galway, the chieftainship of which was that of the Burkes, partly-gaelicised descendants of the Red Earl’s cousin Sir William liath de Burgh, whose chieftain took the Gaelic title of MacWilliam Uachtar or Upper MacWilliam of Clanricarde. Their Anglo-Norman origin was still noted in the early decades of the sixteenth century, with one contemporary commentator referring to the Burkes of Clanricarde as ‘strong herdy men, and of high stature, and nameth them selfes of the Kynges blode, and were Ynglish and berith hate to the Irishhery.’[i]

Robert Cowley, an official of the administration in Ireland at that time, was of the view that the enmity between the Burkes and their Gaelic neighbours, such as the O Kellys and O Maddens, should be harnessed by the English administration for the benefit of the Crown. The castle and town of Athlone was of strategic importance for the protection of the Pale (the area of English influence about Dublin) and the strength of the O Kellys and their proximity to Athlone was a potential threat to the defence of the realm. Given the strength of the Burkes, the ‘mortal grudge’ they bore the O Kellys and O Maddens and their geographical location between the O Kellys and the town of Galway, Cowley was among those who were of the opinion that ‘it shall be right necessary to joyne in oon (one) amytie with theme (the Burkes)’.[ii]

Evidence of the potential effectiveness of this strategy was provided in mid January 1536, when the Earl of Ossory wrote to the Lord Deputy warning him that the Kellys of Uí Maine were preparing to enter Westmeath and support the rebel Thomas Fitzgerald of Kildare. Ossory, on learning of this, ‘sent to McWilliam of Clanricarde and to Richard Burges (Burke’s) sonnes, whiche ben my lovers and frendes, lying in the bake side of the sayde Kellies’ and requested them to attack the Kellys from the west and thereby hamper their ability to go east to Fitzgerald’s aid.[iii] He promised them the ‘Kinges rewarde and highe thankes’.

In another account Ossory described how he ‘did sende to McWilliam and to the olde McWilliam’s sons, to make such warre on the said Okelly, soo that he shud not be suffrid to applye the aiding of Thomas, and promysid theme fermely, aswele the Kinges high favors to their comoditie herafter, as also my rewarde at this tyme and contynuall friendship. Which wele and truely they performed, soo that Thomas was disappoyntid of theme.’[iv]

The McWilliam or chieftain of Clanricarde to whom Ossory referred appears to have been John son of Richard son of Edmund, who held the chieftaincy from 1530 to 1536.

The ‘olde McWilliam’s sons’ appear to have been the offspring of Richard oge Burke who ruled as chieftain from 1509 to 1519.[v] The sons of this Richard Burke, the ‘old’ or former MacWilliam, were at this time a strong force within Clanricarde and their lands lay about Claregalway (also then known as Ballyclare or Clare), Derrymaclaughna, Lackagh, Anbally and elsewhere in the barony of Clare, to the immediate north east of the town of Galway, in what would later be known as County Galway.

The sons and descendants of Richard oge

The sons of Richard oge (ie. ‘the young’) Burke constituted a senior branch of the wider Clanricarde ruling house. Richard oge, from whom they derive their immediate descent, was son of Ulick ruadh or roe (ie. ‘the red,’), MacWilliam of Clanricarde from 1424 to 1485, son of Sir Ulick an fhiona (ie. ‘of the wine’), MacWilliam from 1387 to 1424. The seventeenth century genealogist Dubhaltach MacFirbisigh in his pedigree of the Burkes, gave this Richard oge as ‘of Doire Molt Lachtna’ (ie. the modern townland of Derrymaclaughna, in the parish of Lackagh, County Galway).[vi]

The descendants of Richard oge maintained a high social and political standing within the region of Clanricarde for several centuries thereafter, with the senior-most line seated at the towerhouse of Derrymaclaughna.[vii] In addition to other castles or towerhouses, they appear to have held the castle at Claregalway at this time, which lay in close proximity to the town of Galway and as such was a potential threat to the security of the town.

The tower house of Derrymaclaughna in the parish of Lackagh.

Contest for the chieftaincy 1536

In 1536 the then MacWilliam of Clanricarde, John son of Richard son of Edmund, died and the Irish annalists recorded that a ‘great war broke out in Clanricarde’ concerning the succession to the chieftaincy.

Despite the strength of the sons of Richard oge, one of their number did not attain the MacWilliamship alone. While Ulick, the eldest son of Richard oge was nominated as chieftain, another of the wider family was also nominated, one Richard bacach (ie. ‘the lame’) son of Ulick Burke.[viii]

That same year of 1536 the Irish records known as the Annals of the Four Masters state that ‘the sons of MacWilliam of Clanricard, namely Sean dubh (ie. ‘John the black-haired’) and Remann ruadh (ie. ‘Raymond the red-haired’), two sons of Richard son of Ulick, were slain by the sons of another MacWlliam, ie. the sons of Rickard oge, they being overtaken in a pursuit after they had gathered the preys of that country.’[ix] Both men were killed at ‘Achadh-drainin, according to the Annals of Loch Cé and were, in all likelihood, the sons of Richard bacach (the Four Masters calling Richard bacach ‘the son of Ulick’). As the annalists of Loch Cé described the killers as ‘the sons of Richard oge son of Ulick ruadh son of Ulick na fhíona (ie. ‘of the wine’), they were therefore of the Derrymaclaughna branch.

It is possible that Richard bacach may have been regarded as the principal MacWilliam at this time, as only one MacWilliam is mentioned in 1538 and he is identified as one Richard Burke. This would appear to be borne out by a letter written from the town of Galway in November of 1537 by the merchant Richard Culoke of Dublin. In that letter Culoke only refers to one MacWilliam. He does, however, mention one other prominent member of the wider family; Ulick Burke. As Culoke described this Ulick as kinsman of a clergyman named Roland Burke (later Bishop of Clonfert), he appears to be referring to Ulick na gceann (ie. ‘of the heads’) Burke, another member of the wider ruling house.

This Ulick na gceann was a son of Richard mór (ie. ‘the great’) Burke of Dunkellin, who served as MacWilliam from 1520 to 1530 and therefore it would appear a nephew of Richard bacach. Of his cognomen Sir James Ware held that he was called ‘na gceann’ or ‘of the heads’ ‘because he made a mount of dead men’s sculls, covered with earth, who were slain in a battel.’[x] The Irish annals first refer to him in 1536 as siding with Richard bacach against Ulick son of Richard oge.[xi]

The identity of Richard bacach is uncertain but, as he is given in contemporary accounts as an uncle of Ulick na gceann, he would appear to have been the second of two sons of Ulick finn named Richard, Ulick na gceann’s father being the other Richard. Richard oge, who died in 1519, on the other hand, was a brother of Ulick finn.

The rise of Ulick na gceann

Ulick na gceann’s rise to power coincided with the conflict between the Crown and the powerful Fitzgerald house of Kildare. The Crown moved to take control of Irish affairs out of the hands of the Fitzgeralds of Kildare and at various times appointed Viceroys and Deputies to reform the administration of Ireland in the Crown’s interest. However, despite a number of appointments of English Viceroys at different times, Gerald or Garrett oge, 9th Earl of Kildare, remained the dominant force in the rule of Ireland until 1534.

When the Earl of Kildare was committed to the Tower of London his son Thomas led a rebellion against the rule of King Henry VIII in Ireland. The ninth earl died in English captivity in September of 1534, while the Kildare rebellion was suppressed by the then Lord Deputy Sir William Skeffington in 1535 and Thomas and five of his uncles executed thereafter.

In 1536 Skeffington died and was replaced as Lord Deputy of Ireland by Lord Leonard Gray. Henceforth, in line with Tudor policy, to prevent the possibility of powerful Anglo-Irish nobles dominating Irish politics and acting in their own interest, the government of Ireland would be placed in the hands of English Lord Deputies and the King’s Council in Ireland.

The young Gerald Fitzgerald, son of Gerald 9th Earl of Kildare, was moved for safety during the Kildare rebellion by his allies to O Brien of Thomond and from there to O Donnell in Ulster, far from his enemies. From there he would later escape to the Continent in 1540. The task of capturing Gerald Fitzgerald before he escaped fell to the new Lord Deputy Gray, who was related to Gerald’s mother and therefore regarded with deep suspicion by the Fitzgerald’s traditional enemies, the powerful Butler Earls of Ormond and Ossory in Munster. Ormond and his allies strove to undermine Gray’s authority in Ireland. He further believed that Gray had actively encouraged the Fitzgeralds of Desmond to make war upon him.[xii]

While within the territory of Clanricarde Ulick na gceann Burke sided with Richard bacach in opposition to the sons of Richard oge, he also strove to develop a political understanding with the new Lord Deputy Gray. As an ally of the King’s official representative in Ireland, Ulick would eventually advance to prominence over both Richard bacach and the immediate family of Richard oge.

Ossory’s description in 1536 of the sons of Richard oge Burke as his ‘lovers and frendes’ would suggest an alliance, or at least a political understanding, between Ossory and Richard oge’s sons at this stage. Ulick na gceann was a rival of these sons of Richard oge and was accused by Ossory of being aligned with his enemies, the Fitzgeralds (or ‘Geraldines’). As such and by virtue of his reaching an understanding with the Lord Deputy, he was regarded by Ossory was being in a rival political camp.

Ulick na gceann’s kinsman and the see of Clonfert

While the Lord Deputy negotiated with Ulick na gceann a dispute arose involving the succession to the see of Clonfert and a kinsman of Ulick. Having broken with the Roman Catholic Church over the Pope’s refusal to annul his marriage, King Henry VIII had his Parliament pass the Act of Supremacy in 1534, making the King and his successors the supreme head of the Church in England.

Payments to the Catholic Church and appeals to Rome would be forbidden under later Acts of Parliament. The King and his officials set about the dissolution of monasteries and the confiscation of the rich Church property, selling them on to bolster the Crown coffers. From 1537 to 1541 many Irish monasteries would be suppressed and their lands sold off.

In the west of Ireland the King promoted one Doctor Richard Nangle as his nominee to the see of Clonfert. As the King’s candidate, he was consecrated in 1536. He was opposed, however, by Ulick na gceann’s first cousin Roland, son of Redmund Burke of Tynagh, who obtained a provision for the same see from the Pope.

Although he had the support of the King, Nange found himself isolated in the town of Galway at this time as a result of the support shown by both the then MacWilliam and Ulick na gceann for their kinsman. Richard Culoke wrote from Galway in November of 1537 to the King’s Treasurer in Ireland William Brabazon, informing him of Roland’s arrival from Rome with the Pope’s provision to Clonfert. Until Roland’s recent arrival Nangle had enjoyed possession of the bishopric but since Roland’s arrival Nangle dared not travel outside the town. Culoke understood the stance of the MacWilliam and Ulick na gceann as vital to ensuring Nangle’s holding of the see and requested Brabazon to either write secretly to the MacWilliam and Ulick and have them send Roland to Dublin to answer to the King’s law or to have the Mayor of Galway withhold revenues from that town until both men secure Nangle in possession of Clonfert.[xiii]

The Lord Deputy Gray’s efforts to secure Ulick na gceann as an ally in Clanricarde meant that he was loath to upset Ulick and appears to have prevented Gray acting to support Nangle. Despite being the King’s nominee, without the Burke’s support Nangle was forced to depart the west, leaving Roland in possession. While the King ordered that Nangle be restored to the see, the strength of the Clanricarde family locally ensured that Roland Burke, as the Pope’s nominee, remained in possession despite the King.

Advancement of Ulick na gceann to the office of MacWilliam Uachtar

Lord Leonard Gray undertook a progress through Leinster and Munster in June of 1538, in an attempt to exert the Crown’s authority over a wider area, receiving the submissions of many of the local chieftains and rulers as he went. On his camping in the small Munster territory of the O Mulryans on the 26th June he was approached by, among others, Ulick na gceann, who formally submitted to the King’s authority. Ulick appears to have departed from the Lord Deputy immediately thereafter, while the latter proceeded to the town of Limerick and on to O Brien’s county of Thomond, about the modern county of Clare. From there Gray prepared to enter the territory of Clanricarde in what would appear to have been a pre-arranged plan with Ulick na gceann to replace the ruling Burke chieftain with his own ally.

The Lord Deputy travelled through Connacht with a small retinue of soldiers and supporters, reputedly taking only ‘one hundred Englishmen and two battail of gallogles (galloglass) and thirty Irish horsemen and a couple of faucons.’ His political opponents, including the Butler Earl of Ormond and Ossory, criticised him for creating the impression that the King had no stronger forces at his disposal and criticized his support for Ulick na gceann, whom he regarded as being in league with the FitzGeralds, then at odds with the King. Ormond’s allies in the Kings Council in Ireland were also of the same view, informing Cromwell, the King’s Secretary, that Ulick was ‘of the Geraldyne (ie. ‘Fitzgerald’) bande’, claiming he assisted in conveying the young rebel Gerald Fitzgerald and his aunt, sister of the Earl of Kildare, from O Brien’s territory to the safety of Manus O Donnell in Ulster between whom a marriage alliance was planned.[xiv]

The assault on the castle and abbey at Claregalway

During his expedition through Clanricarde a contemporary report stated that the Lord Deputy ‘put down MacWilliam, which was capitayne of the countrie at his coming’ and ‘made oon Ulicke de Burgo capitayen.’[xv] From contemporary accounts it would appear likely that the ruling MacWilliam suppressed by the Lord Deputy was Richard bacach.

In addition to unseating Richard bacach, Gray also moved against the descendants of Richard oge Burke, Ulick na gceann’s rivals.

In a report of his activities to King Henry VIII, Gray recounted that on the 9th of July 1538, travelling northwards from O Brien’s country, he ‘repayrid to the Burgh’s countrey, called Clanricard, and theyr camped that nyght.’[xvi] He was met on the border of the country by Ulick na gceann with about twenty three men on horseback.[xvii] Gray left Ulick the following morning (either the 10th or 11th July) with the ordnance and went travelling on forward without him, ‘repayryd to a castell, called Bally Clare, (Claregalway castle) belonging to Rychard Ogh Burgh, which dyd much hurt to (the King’s) towne of Galwey, and the same dyd take, and delyver to Ullyck Obrogh (Burke), now latelye made chief capitayn of that counter, and great frynde’ to the town of Galway. A critic of the Lord Deputy attributed the taking of the castle to the speed of the Lord Deputy’s arrival and, at their sudden arrival, ‘the castell of Clare was lefte up by the warde and ymediately delyverid the same to Ullike Bourke for mony.’[xviii] On the same occasion the friary at Claregalway was raided ‘and neither chalice, cross nor bell left in it.’ Gray then camped there that night.[xix]

The attribution of Richard oge as the occupier of Ballyclare or Claregalway castle by the Lord Deputy would appear to have been an error, given that he moved at that time against the sons of Richard oge and Richard oge had died in 1519.[xx]

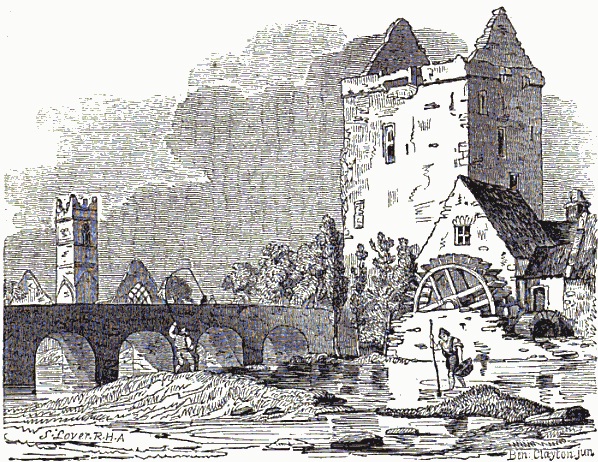

Ballyclare or Claregalway Castle in the early nineteenth century, with the ruins of the friary church to the west in the background. (The Irish Penny Magazine, No. 6, Vol. 1, Dublin, 9 February 1833, p.41. Drawn by Samuel Lover RHA for The Irish Penny Magazine.)

Ulick travelled with Gray the following day into the town of Galway, where Gray was welcomed by the mayor ‘and his brothren’, who covered the cost of sustaining the Englishmen in the retinue, while Ulick Burke provided for the costs of the Irish from his territory in the Deputy’s company. There, as he did in Limerick, Gray addressed himself to the town’s mayor and leading citizens and the then Archbishop of Tuam, requiring them to take an oath under the Act of Supremacy, acknowledging the King as the supreme head of the Church in his realms and requiring them to renounce the authority of the Pope.

While Gray was in Galway both Melaghlin and Hugh O Madden, whose territory of Síl Anmchadha in east Galway lay to the east of Clanricarde, came to the town and, with O Flaherty and MacFheorais of Athenry (or Bermingham), submitted to the King’s authority.

Gray’s enemies reported that, while in the town of Galway, Gray ‘made the said Ullucke a knight and created hym being a bastard mcWilliam and expulside his uncle Ricard de Borke.’[xxi] Official records recording the knighting of Ulick by the Lord Deputy in the town of Galway on the 13th July 1538 refer to him as the ‘Captain of Clanrickard.’[xxii]

As the then MacWilliam, Richard Burke, appears to have been Richard bacach and he was referred to as an uncle of Ulick na gceann, it would imply that he was a son of Ulick finn Burke of Knocktoe, MacWilliam from 1485 to 1509. This suggests that Ulick finn had two sons named Richard, as Ulick na gceann’s father was also a Richard.

The assault on the castles of Lackagh and Derrymaclaughtny

After spending about six days in the town, Gray departed on the 18th and re-entered the territory of Clanricard.[xxiii] He travelled northeast, immediately beyond Claregalway castle, into the lands of the sons of Richard oge about the parish of Lackagh.

One of those who travelled with Gray, a critic of his, later related that he ‘marched with the said newe mcWilliam to Leakagh and Deryviclaghhyn, two castells belonging to Ricard Ogs sonnies, whiche proffered to be come the Kingis faithfull subjects, and to do his majestie dayly srvice and to yeld, and pay yerely to the Kinge as moche rent and tribute out ther castells as the said Ulluck would give so as by reason of there….they would not be bounde to be under the subjeccon of the said Ullick, being ther younger, onles the Kings consaile to whome they were contentide to put the indifferent ordering of that mater would (award) them; which the lord deputie refuside and brake downe there said two castellis and camped ther ii nights and ii dayes brekyng the said castellis and cutting ther corne.[xxiv]

The ruins of Lackagh Castle, near the hill of Knockdoe, between the castles of Claregalway and Derrymaclaughna, viewed from the remains of the nearby late medieval church.

Gray’s critics would later claim that ‘Ulick Burk, a bastard, gave him 100 marks to have ‘Ballimacleere castle’ (ie. Ballyclare or Claregalway) and to be made MacWilliam’, ‘that he rifled the abbey of Ballyclare (Claregalway) and left in it neither chalice, cross nor belt’ and that ‘he destroyed Lecagh and Derriviclaghny in favour of Ulick Burk, though the rightful proprietor offered submission and rent to the king.’ He was moreover accused, among other serious claims, of partiality to ‘his nephew FitzGerald (ie. the young Gerald), afterwards Earl of Kildare.’[xxv]

He thereafter progressed to the borders of O Kelly’s country, where O Connor Roe made his submission and on the 22nd July passed through O Madden’s country, where he received ‘three score kine’ from the two ruling O Madden joint-chieftains. Crossing the Shannon at the ford of Banagher, where he stayed that night, he proceeded thereafter into MacCoghlans territory.[xxvi]

It is clear from the account of Viscount Gormanstown, who accompanied Gray on his expedition through Connacht, that Ulick na gceann was regarded as more junior or less entitled to the chieftaincy than the sons of Richard oge and that his legitimacy was in question.

The wives of Sir Ulick na gceann Burke, MacWilliam of Clanricarde

Ulick na gceann’s marital situation was such that, after his death, it would prove difficult to determine which of his offspring, if any, should inherit his position as the legitimate heir under English law.

Ulick na gceann was married three times, first to Graine ny Kervill (ie. Grainne Ni Carroll, daughter of ‘Mulrone’ O Carroll, chieftain of the O Carrolls of Eile in Leinster) ‘who was alive at the time of his marriage with his last wife Dame Marie Lynch. This first marriage was solemnised in Church and its validity accepted after investigation later by the Crown.[xxvii]

Graine was still his wife when he married Honora Burke, sister of Ulick Burke of Cloghroak, of a significant and influential branch of the name established in the baronies of Dunkellin and Kiltartan in what would later be south-west County Galway. This second marriage was also solemnised in a church. Ulick na gceann was found to have divorced or put aside Honora, but it could not later be proven if this was legally or lawfully effected. He thereafter married one Mary Lynch.[xxviii]

Mary Lynch was daughter of a wealthy merchant of Galway town. Ulick was reputed to have entered into this third marriage to avail of her anglicizing influence as he drew closer to the Crown and built upon that early alliance.

Ulick’s marital position was further complicated in that his second and third wives later claimed that his first marriage, to O Carroll’s daughter, was invalid. They claimed that a considerable time before Ulick’s first marriage was solemnized Graine had been lawfully married to one ‘O Mollaghlen’, the chieftain of the O Melaghlins.[xxix]

The immediate family of Sir Ulick na gceann

Ulick na gceann had at least five sons; Thomas farranta (ie. ‘the athletic’), Richard Sassanach (ie. ‘the Saxon’ or ‘Englishman’), John or Seaan, Redmond and Edmund.

Thomas would appear to have been the eldest but it is possible that he may have been illegitimate and unable to lawfully inherit under English law. He was of an age to act and take custody temporarily of his father’s castles after his death. No provision was made for his possible succession to his father’s position when the Crown would later investigate the cases of those eligible to inherit in 1544 and he was alive in 1545 when he received a pardon from the Crown.[xxx] This would suggest that he was not a lawful heir.

Richard ‘Sassananch’ was still a minor in 1543 and was son of Ulick na gceann’s first marriage to Graine Ni Carroll.[xxxi]

It is unclear if any children were the product of Ulick’s marriage to Honora Burke but John, who would later press his claim as the next in line to inherit if Richard was not found to be legitimate, was the son of Ulick’s third marriage to Mary Lynch.[xxxii]

Ulick’s sons Redmond and Edmond, the former later seated at Clontuskert and Bealanean in east Galway and the latter seated at Ballylee castle near Gort in south west Galway (in later centuries the home of the poet W.B. Yeats) were significant figures in the later political landscape.[xxxiii] Redmond appears to have been the more prominent and may have been the elder of the two. His mother was given by MacFirbisigh in one variation of the family pedigree in his ‘Great Book of Irish Genealogies’ as Fionnghuala, daughter of O Kelly.

Ulick na gceann had at least one brother; William Burke of Rahally. This William was described as ‘of Rahale’ when, in the reign of Phillip and Mary, sometime after 1554, he was granted by the Crown the lease of the suppressed priory of Clontuskert Uí Maine and its possessions.[xxxiv] ‘Rahale’ is elsewhere given as Rahally or Rathalla in the barony of Kiltartan in County Galway, where William’s son Richard, born about 1551, appears to have resided there in the late sixteenth century.[xxxv] This family resided at Rahale castle into the seventeenth century.[xxxvi]

The Crown policy of Surrender and Re-grant

Henry adopted a conciliatory approach to Irish and Anglo-Norman chieftains, in an effort to bring them peacefully under his influence, and avoid endless and costly wars. The Crown offered those chieftains it approached legal title under English law to their lands. The chieftains would surrender their lands to the King and their right to rule under Gaelic law, recognise the Kings authority and receive their lands back at the hands of the King, as his loyal vassals. In accepting this re-grant the chieftains ensured the succession to the chieftaincy would now follow the English system of primogeniture, the chiefs lands going directly to the eldest son, instead of the Gaelic system of election of the fittest to rule.

Adherence to English law of inheritance also had significant implications for members of the wider ruling house of the Burkes of Clanricarde who, under Gaelic law, would have been eligible to attain the Gaelic chieftaincy and access to the territories castles and lands attached to the office of MacWilliam. Acceptance of English law would render these branches ineligible in the future to attain overall power within the territory.

It was regarded as necessary for the ruling MacWilliam chieftain to avail of this policy and surrender his lands in a similar manner to other Gaelic lords and have them re-granted under English law, as they held their lands without title under English law. In the eyes of the Crown and English law ‘McWilliam held not other lands, in effecte, but parcel of the Erledom of Ulster,’ a reference to the fact the former lands of the de Burgh Earls of Ulster and Lords of Connacht, following the murder of the Brown Earl of Ulster in 1333, passed, through heiresses, into the hands of the Crown.

Leonard Gray was recalled to England in disgrace in 1540, his military expeditions about the country having led to unrest and rebellion against his rule. Charged with treason and executed thereafter, he was replaced as Lord Deputy by the less aggressive Sir Anthony St Leger, with whom Ulick na gceann dealt in relation to the surrender and re-grant of his lands.

Advancement to the title and dignity of Earl of Clanricarde

King Henry VIII wrote to Ulick na gceann from Greenwich dated May 1st 1541 and offered him the title of a baron or viscount, but stated that he would not grant him an earldom ‘unless he will come to court.’[xxxvii]

Ulick na gceann requested the Lord Deputy and the Council to make representations to the king on his behalf. He was eager that the Crown, in addition to granting him a title of honour, ‘as others his auncestours have had’, ‘confirm his estate in suche landes and possessions, as he at this present enjoyeth, to be holden of (the King) by knights service, to hym and to his heires males of his body lawfully begotten, and for defaulte therof to remayne to his brother, William Burke, and his heires males of his body lawfully begotten’, together with other rents, customs and profits he claimed were his due in Galway, Clanricarde and Connacht.[xxxviii]

Ulick’s petition to the Lord Deputy and Council

Ulick petitioned the King through the Lord Deputy St Leger and the King’s Irish Council, renouncing ‘the name of McWilliam and to have some name of honor according to the Kinges most gracious graunte.’ He sought to be made ‘Grande Capitayne of his countrey, as thErles of Ormonde and Desmonde ar in ther confines,’ and undertook to renounce Gaelic brehon law and to abide by and execute English law everywhere under his rule.[xxxix] (Although renouncing Gaelic law, he petitioned that traditional rents due to the office of MacWilliam known as ‘rents of defence,’ be confirmed upon him ‘that he may receive them of the Kinges gyfte.’)[xl]

While seeking the King’s pardon, he presented a number of requests, not all of which would be granted. He first sought the fee farm of the town of Galway, claimed as his by right of his ancestors holding the same ‘for time out of mind,’ reserving for the King the gift of all ecclesiastical benefices within the town. In addition he sought the holding of Roscommon Castle, then he claimed in O Connor’s possession ‘by usurpation’ and sought possession of the two castles of Meelick and Banagher on the River Shannon, then in the custody of O Madden.[xli]

He sought the cockets ‘of Sligo, Porterade and Leighborne, and all other creeks and havens’ which he claimed his ancestors formerly held and a portion of the first fruits of certain ecclesiastical benefices and the appointment of various church positions within his territory. [xlii]

At that time Ulick detained the castle of ‘Tecoyne, in Okelleys countrey’ and sought the castle of Moycullen, north of Galway, from the O Flaherty chieftain and ‘Turrowen’, again claimed by Ulick as held by his ancestors.[xliii]

In his petition he outlined the principal manors that he claimed were then in his possession as ‘the townes of Loghregh, Claer, Cloncastell, Baleforwer and Leytrom.’ These, he asserted, had been built by his ancestors and he now sought to have them confirmed as his under English law.[xliv]

For his part, Ulick also agreed to hold his property of the King and pay to the King an annual rent of ten pounds sterling initially and more thereafter ‘when yt (the territory) ys reduced and brought to better cyvilite.’ To this petition Ulick na gceann put in pledge his son Richard, then a minor, to the Lord Deputy.[xlv]

Having previously undertaken that he would travel to England to the court of King Henry VIII, he was preparing to do so by 1543. In advance of his arrival his petitions were summarised for consideration by the King. His request that he, his children and his servants be granted a general pardon by the Crown was agreed, but his request that he be given ‘the rule and office of a captaine in the countie of Connaght, and to have the leading and governaunce of his cousins and kynsmen’ was refused. In addition to other requests he petitioned to be created ‘Erle of Connaught, and have that name to hym, and to his heires males, with landes sufficient to maynteign the name of the Erle.’[xlvi] In keeping with his claim to the title of Connacht he demanded ‘the towne and castell of Sligo, with certaine rentes in the northe partes of Connaught, and the arrerages of the same, wrongfully, as he saith, detained many yeres by Odonell, Orowrke and other, and specially the rents of Clainewilliam (the Mayo Bourkes)’ and sought rents in Tirawley.

The Lord Deputy and his Council in Ireland had advised the king in May of 1543, in advance of the petition, that if Ulick should ask for the title of Connacht, it be refused, it being geographically one fifth of the realm and therefore inappropriate. They informed the king that Ulick sought more than he already possessed, and more than they believed he should be granted. While they previously granted certain of his requests, they deferred making a clear decision on others. They were keen, however, to placate Ulick as far as possible to maintain his continued allegiance without conceding to what they regarded as his more excessive demands.[xlvii] The Lord Deputy and Council did, however, ask the king to be generous to Ulick, thereby encouraging him ‘to persiste and contynue in his honeste procedinges so well begonne.’ They were of the opinion ‘considering that by his wisdome and pollycie he hath reduced those savage quarters, under his power and rule, to moch better cyvilitie and obedience than they have ben of many yeares paste’ that Ulick should be assured not only of the lands, rents, tenements and services he then possessed in Clanricarde and elsewhere, but that he should be advanced to the title and dignity of an earl, but to create him Earl of ‘Clanrycarde.’[xlviii]

For aligning himself with King Henry, Ulick na gceann was created 1st Earl of Clanricard and Baron of Dunkellin in July of 1543 and received a re-grant of his estates at the king’s hand. In addition to securing the lordship lands for his own immediate descendants under English law, the re-grant provided his family with legal title to their estates that, under English law, had rightly been the property of the descendants of the Brown Earl’s daughter.

The investiture ceremony at Greenwich 1543

The three Irishmen; Morogh and Donogh O Brien and Ulick Burke were in England by the beginning of June and made their submissions before the King on the 3rd June 1543.[xlix]

Ulick na gceann Burke was created Earl of Clanricarde and Baron of Dunkellin on Sunday 1st July 1543 at the King’s manor of Greenwich by King Henry VIII. On that same occasion the King created Morogh O Brien Earl of Thomond and Donogh O Brien Baron of Ibracken. Their order of creation on the day was Thomond was created first, Clanricarde second and Ibracken third.

The ceremony was described in detail by a contemporary present. “Firste, the Queenes closet at Greenewich was richly hanged with cloth of arras, and well strawed with rushes. And after the Kinges Majestie was come into his clossett to heare High Masse, these Earles and the Baron aforesaid, in company, went to the Queenes closet aforesaid, and there, after sacring of High Masse, put on their robes of estate; and ymediately after, the Kinges Majestie being under the Cloth of Estate, with all his noble Counsell, with other noble persons of his Realme, aswell spirituall as temperall, to a great nomber, and the Ambassadours of Scotlande, the Earle of Glencarne, Sir George Douglas, Sir William Hamelton, Sir James Leyremonthe, and the Secretary of Scotlande, came in the Earle of Tomonde, lead between the Earle of Derby and the Earle of Ormonde, the Viscount Lisle bearing before him his sworde, the hilt upwards, Gartier before him bearing his letters patentes; and so proceeded to the Kinges Majestie. And Gartier delivered the sayd letters Patentes to the Lord Chamberlaine, and the Lord Chamberlaine delivered them to the Great Chamberlaine and the Lord Great Chamberlaine to the Kinges Majestie; who tooke them to Mr. Wryothesley, Secretary, to reade them openly. And when he came to “Cincturam Gladii,” the Viscount Lisle presented to the king the sworde; and the Kinge gyrded the sayd sworde about the sayd Earle bawdricke-wise, the forsayd Earle kneelinge, and the Lordes standing that lead him. And so the pattent read out, the second Earle being brought into the Kinges Majesties presence by the two Earles aforesaid, was created there, in every thing according to the seremony of the first Earle. That done, came into the Kinges presence the Baron, in his kirtell, lead between two Barons, the Lord Cobham and the Lord Clinton, the Lord Montjoye bearing before him his robe, Gartier before him bearing his letters patentes in manner aforesaid, who then proceeded to the Kinges Majestie, and His Highnes receaved the letters patentes in manner aforesaid and tooke them to Mr. Pagett, Secretary, to read them openly. And when he came to “Investimus,” he put on his robe. And so the patente read out, the Kinges Majestie putt aboute every one of their neckes a cheine of gould with a cross hanging at yt, and toke them theire letters pattentes, and they gave thankes unto him. And there the Kinges Majestie made five of the men that came with them, Knights. And so the Earles and the Baron, in order, tooke theire leave of the Kinges Highnes, and weare conveyed, bearing their letters patentes in theire handes, to the Councell Chamber underneath the Kinges Majesties Chamber, appointed for their dyninge place, in order as hereafter followeth; the trumpettes blowinge before them; the Officer of Armes; the Earle of Tomond, lead between the Earle of Derby and the Viscount Lisle; the Earle of Clanryckard, lead between the Earle of Ormonde and the Lord Cobham; the Baron Ybracken, lead between the Lord Clinton and the Lord Montjoye; and thus brought to the dining place. After the second course, Gartier proclaymed theire stiles in maner folowinge: “Du Treshault et Puissant Seigneur Moroghe O Brien, Conte de Tomond, Seigneur de Insecoyne, du Royaulme de Irelande. Du Treshault et Puissant Seigneur Guillaume Bourghe, Conte de Clannryckard, Seigneur de Downkelleyn, du Royaulme de Irelande. Du noble Seigneur Donoghe O Brien, Seigneur de Ybrakan, du Royaulme de Irelande.” The Kinges Majestie gave them theire robes of estate, and all thinges belonging thereunto, and payd all manner of duties belonging to the same.”[l]

The King thereafter wrote to his Lord Deputy and Council in Ireland to confirm his creations and to clarify what had been agreed. With regard to Ulick, the King confirmed that he ‘graunted the same estate to him, and his heires masles of his body lawfully begotten, and have also given unto them all the landes whiche be now in his possession.’ He withheld the revenue form the cockets of the town of Galway, reserving those profits to the Crown. Instead he granted him an annuity from the Crown lands there. He was granted the right under English law to determine appointments to the parsonages and vicarages within his own territory, with the exception of the office of Bishop. He was further granted a third part of the ‘first fruits’ from the same ‘towards the maytenaunce of his estate.’ He and his heirs male were also granted the ‘Abbey de Via Nova’ (also known as Monaster O Gormagan or Abbeygormacan) in the diocese of Clonfert, which was at that time already in the possession of his son. (The identity of his son is uncertain but it was in all likelihood his son Thomas.)[li] He was, in addition, like the other peers elevated that day, granted a house and plot of land near Dublin, ‘for the keeping of their horses and traynes’, to facilitate their attendance at Parliament and Council meetings in England. This latter grant, however, remained unfulfilled at the time of the Earl’s grant and still sought by his heir some time later.

At the same time the King confirmed Ulick’s kinsman, Roland Burke, as Bishop of Clonfert ‘so that he cancel and utterly renounce the Bulls of the Bishop of Rome’ and granted that ‘the monastery of Porta Pura (ie. Clonfert) should be united to that Bishoprick.’[lii] Roland had petitioned that the vacant see of Elphin be united to that of Clonfert for his benefit. Claiming that the parish church in Loughrea was then in ‘greate ruyne and decaye’ he also petitioned that the Dominican abbey ‘joyning thereto, having no landes longing to it but certaine chaepllis under it’ be given the status of the parish church. In addition to other grants to Roland, the King granted Roland’s petition regarding the Loughrea abbey, which may have been intended by Roland as a means to prevent its dissolution as a monastery church but refused to unite the see of Elphin to that of Clonfert.[liii]

Among the men he knighted also on that occasion was O Shaughnessy, whose lands lay about Gort (or ‘Gortinseguaire’) to the south of Galway, and granted to those he knighted ‘their lands on their submission and requesting that they should not suffer any damage but that the Deputy should aid them and see them revenged as the case should require.’[liv]

Death of Ulick 1st Earl of Clanricarde

Ulick na gceann did not survive long to derive significant benefit from his elevation to the peerage. The Irish annalists reported for that same year that ‘MacWilliam of Clanrickard, Ulick na gceann, and O Brien went to England and were both created earls and they returned home safe, except that MacWilliam had taken a fever in England from which he was not perfectly recovered.’[lv] He died soon thereafter.

The relationship with the Crown’s administration in Ireland developed by Ulick Burke was of significance for the descendants of Ulick and for those who, under the Gaelicized system of government would have been entitled to compete for the office of MacWilliam of Clanricarde. Ulick’s legitimate successors would, under English law, succeed to the lands and entitlements that would, under Gaelic law, formerly have been attached to the office of MacWilliam.

The Gaelic records state that, on death of Ulick na gceann in 1543, a great war broke out for control of the lordship.

At about the same time that the King’s Commissioners entered the territory following the Earl’s death, the sons of Richard oge and their supporters proclaimed Ulick, the eldest of the sons of Richard oge as MacWilliam ‘after the oolde Irishe sorte.’[lvi] (This was the same Ulick who had been one of the two nominated for the Gaelic chieftaincy of the territory seven years earlier).[lvii] Ulick and his party sought to take the dead Earl’s castles and garrisons about the territory and killed a number of the Commissioner’s men outside of the town of Athenry. In opposition to the sons of Richard oge, the Commissioners placed the custody and defence of the late Earl’s castles temporarily in the hands of the Earl’s son Thomas farranta, with the assistance of others.[lviii]

Neither of these two rivals, however, would appear to have been eligible under English law to succeed to the position or property held by Ulick na gceann if it could be proved that he had legitimate male issue by his wives. But immediately following his death, it was uncertain if he had any legitimate heir male, as, in the words of the King’s Lord Justice in Ireland at that time ‘ther were so many marriages and divorces.’[lix]

[i] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1515-1538, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p.328. R. Cowley to Cromwell, 1536.

[ii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1515-1538, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p.451. R. Cowley to Cromwell, 1537.

[iii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1515-1538, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 229-30.

[iv] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1515-1538, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 252.

[v] While the sons of another Richard, who served as MacWilliam from 1520 to 1530 were also active about this time, this would appear to be a reference to the sons of Richard oge who served as MacWilliam and died in 1519, given their political prominence at this time in the territory of Clanricarde.

[vi] Ó Muirile, N. (ed.), MacFirbhisigh, D., Leabhar Mór na nGenealach, The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, compiled (1645-66), Vol. III, Dublin, de Búrca, 2003, pp.110-1, no. 798F.5.

[vii] Later references to members of the family of Derrymaclaughtna, descended from Richard oge, bear out this Richard oge as son of Ulick ruadh or roe (ie. ‘the red-haired) Burke. The Annals of the Four Masters record that in 1572 ‘John the son of Thomas son of Richard Oge son of Ulick Roe son of Ulick of the Wine was drowned in the River Suck.’ The same source states that in 1598 ‘Rickard the son of John son of Thomas son of Rickard Oge Burke from Doire mic Lachtna died in the month of August.’ Both individuals appear to be of the one line and give the line of the Derrymaclaughtny family as descended from Richard oge son of Ulick roe son of Ulick ‘na fíona’ or ‘of the wine’. Their continued senior status within the wider family and the territory of Clanricarde was taken into account in the Composition of Connacht in 1585.

[viii] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, 1536. No. 4.

[ix] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters. 1536. No. 18. (Some translations of this account given in the English language say that the two brothers were killed by the sons of ‘the other MacWilliam, ie. of Richard og’, suggesting that one Richard oge was at that time one of two MacWilliams who were ruling at the same time. The original Irish language reference gives the killers simply as ‘clann Mic Uilliam eile, i. clann Riocaird Oicc.’ This is more accurately the family or ‘sons of another MacWilliam, ie. Richard og’ and does not necessarily imply that they were sons of a ‘sitting MacWilliam’ but rather that they were sons of Richard oge who at least at one time held that office.

[x] Ware, J., The antiquities and history of Ireland, Dublin, E. Dobson & M. Gunne, 1705, p. 111. MacFirbisigh identifies Richard mor as father of Ulick na gceann and ‘of Dun an Choillin’ in his ‘Great Book of Genealogies.’

[xi] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, 1536. No. 4.

[xii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 54. Ormond to R. Cowley.

[xiii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1515-1538, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p.516. CLXXXVIII, Culoke to Brabazon, 1537.

[xiv] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 78. ‘Certain articles putto the Kinges Highnes most honorable Counsaill by thErle of Ormond and Osserrie, wherein he fele hymsilf greved by the Lord Deputie.’ Also pp. 55-57. CCXLIII, Brabazon, Aylmer and Alen to Crumwell.

[xv] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 55-57. CCXLIII, Brabazon, Aylmer and Alen to Crumwell.

[xvi] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 57-61. CCXLIV. Gray to King Henry VIII.

[xvii] G. Power, (W. Brabazon, G. Aylmer, J. Alen), The Viceroy and his critics: Leonard Grey’s journey through the west of Ireland June-July 1538, JGAHS, Vol. LX, 2008, pp. 78-87. ‘The confession of the Viscount Gormanstowne, oon of the Kings most honourable counsaile, John Darsey and William Brymigham, esquires, concerning theffects and proceedings of this my lord deputies jo’nay into Monister Thomond and Conaghte &c.’ O Brien provided only one galloglass with an axe as the Lord Deputy’s guide into Clanricarde. On the night of their departure from O Brien’s territory, they encamped on ‘the edge borthring between oBrens counter and Clanrycarde wathcinge all that nyght in ther harneys and ther came Ullucke de Burke to his lordshupe with aboute twenty three men on horsbake. And the said Ullucke mervailinge that my lord deputye would come so stlenderly in so daungerous a passag demaunded of hym how he durst come in that maner. And he pointid saing ‘lo, seist thou not yonder standing befor me, o Brens axe my conduct?’

[xviii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 52-55. CCXLII, Ormond to R. Cowley.

[xix] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 57-61. CCXLIV. Gray to King Henry VIII. Footnote no. 4.

[xx] Gray in other contemporary correspondence written to King Henry VIII stated that ‘on the 19day of July I retornyd from Galwey into Clanrycard, 8 myles from Galwey; and theyr I toke and brack (ie. ‘took and broke’) twoo castelles of the sayd Rychard Ogh Burgh.’ This is a reference to the castles of Lackagh and Derrymaclaughtny which he assaulted on that day and both would appear to have been held at that time by the sons of Richard oge rather than Richard oge. In this same letter to the King, Gray referred to the castle of Bally Clare (Claregalway) as ‘belonging to Rychard Ogh Burgh.’ (Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 57-61. CCXLIV. Gray to King Henry VIII.)

[xxi] G. Power, (W. Brabazon, G. Aylmer, J. Alen), The Viceroy and his critics: Leonard Grey’s journey through the west of Ireland June-July 1538, JGAHS, Vol. LX, 2008, pp. 78-87. ‘The confession of the Viscount Gormanstowne, oon of the Kings most honourable counsaile, John Darsey and William Brymigham, esquires, concerning theffects and proceedings of this my lord deputies jo’nay into Monister Thomond and Conaghte &c.’; Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 78.

[xxii] Shaw, W.A., The Knights of England, incorporating a complete list of Knights Bachelors dubbed in Ireland compiled by G.D. Burtchaell, Vol. II, Sherratt and Hughes, London, 1906, p. 52.

[xxiii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 57-61. CCXLIV. Gray to King Henry VIII. Both ‘Leakagh and Deryviclaghhyn’ were identified as the castles in question in another detailed report on the Lord Deputies journey through Munster, Thomond and Connacht, provided by Viscount Gormanstown, John Darsey and William Bermingham.

[xxiv] G. Power, (W. Brabazon, G. Aylmer, J. Alen), The Viceroy and his critics: Leonard Grey’s journey through the west of Ireland June-July 1538, JGAHS, Vol. LX, 2008, pp. 78-87. ‘The confession of the Viscount Gormanstowne, oon of the Kings most honourable counsaile, John Darsey and William Brymigham, esquires, concerning theffects and proceedings of this my lord deputies jo’nay into Monister Thomond and Conaghte &c.’

[xxv] Wynne, J. H., A General History of Ireland from the earliest accounts to the present time, Vol. II, Dublin, D. Chamberlaine, W. Sleator, J. Potts, T. Walker and C. Jerkin, 1773, p.56-7.

[xxvi] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 57-61. CCXLIV. Gray to King Henry VIII. The crossing at Banagher ford, where the Lord Deputy then stayed the night, was recounted in another detailed report on the Lord Deputies journey through Munster, Thomond and Connacht, provided by Viscount Gormanstown, John Darsey and William Bermingham.

[xxvii] Brewer, J.S. and Bullen, W. (ed.), Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, 1515-1574, First published on behalf of P.R.O., London, 1867, pp. 211-213.

[xxviii] Brewer, J.S. and Bullen, W. (ed.), Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, 1515-1574, First published on behalf of P.R.O., London, 1867, pp. 211-213.

[xxix] Brewer, J.S. and Bullen, W. (ed.), Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, 1515-1574, First published on behalf of P.R.O., London, 1867, pp. 211-213.

[xxx] Morrin, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Patent and Close Rolls of Chancery of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, Vol. I, Dublin, Alex, Thom & sons, 1861, p. 110. He was described therein as ‘Thomas Burke of Clanrycarde, son of William Burke, late Earl of Clanrycarde, horseman’ when issued a pardon by the Crown at the end of November 1545. The Irish annalists give his death as occurring in that same year, following a raid into the territory of the O Maddens.

[xxxi] Brewer, J.S. and Bullen, W. (ed.), Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, 1515-1574, First published on behalf of P.R.O., London, 1867, pp. 211-213.

[xxxii] Brewer, J.S. and Bullen, W. (ed.), Calendar of the Carew Manuscripts, 1515-1574, First published on behalf of P.R.O., London, 1867, pp. 211-213.

[xxxiii] Edmund Burke fitzUlyck of Ballyley (ie. Ballylee) was granted a pardon in 1574, where he is pardoned alongside Coagh O Madden of Clare. (Cal. Fiants Eliz. I) At his death in the Summer of 1597, the Annals of the Four Masters give him as Edmond of Baile-Hilighi, son of Ulick na gceann son of Richard son of Ulick of Cnoc tuagh.

[xxxiv] Fanning, T., Dolley, M. and Roche, G., Excavations at Clontuskert Priory, Co. Galway, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, Vol. LXXVI, 1976, p. 103.

[xxxv] Fahey, J., D.D., V.G., The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Kilmacduagh, M.H. Gill & sons, Dublin, 1893, p. 254.

[xxxvi] Rahally in the barony of Kiltartan was occupied about 1574 by one Richard Burke. One Ricard Bourke of Rahalle was at the top of a list of individuals of County Galway pardoned by the Crown in 1583. (Calendar of Fiants Queen Elizabeth I, The thirteenth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records in Ireland, 12 March 1881, Dublin, A. Thom & Co., 1881, Appendix, Fiants, Eliz. I, p.204, No. 4140.) He would appear to be son of this William of Rahale as he was described as ‘Rickard McWilliam (i.e., son of William) of Rahale’ when listed among the twenty-five chief men of the territory of Clanricard at the 1585 Composition of Connacht, making him a first cousin of Richard, 2nd Earl of Clanricarde. About 1615 he gave his age in a deposition regarding O Shaughnessy property as ‘sixty-four years old or thereabouts.’ (J. Fahey D.D., V.G., The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Kilmacduagh, M.H. Gill & sons, Dublin, 1893, p. 254.) In the 17th year of the reign of King James I, Richard Bourke of Rathalla, gentleman, held the castle and quarter of Rathalla in Kiltartan barony and one eighth of the two quarters of Cahernemuck in the barony of Loughrea, while John Bourke McRichard of Rathalla, who appears to have been this man’s son, held an eighth part of the two quarters of Cahernemuck. (Cal. Pat. Rolls, 17 James I, p. 440.)

[xxxvii] Hamilton, H.C. (ed.), Calendar of State Papers relating to Ireland of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1509-1573, London, Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1860, p.58.

[xxxviii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 455-6. CCCXC. The Lord Deputy and Council to King Henry VIII.

[xxxix] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 359-361.

[xl] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 359-361.

[xli] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 359-361.

[xlii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 359-361.

[xliii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 359-361.

[xliv] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 359-361.

[xlv] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 359-361.

[xlvi] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 463-4. CCCXCIII. An Abregement of the Irisshmens Requestes.

[xlvii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 455-6. CCCXC. The Lord Deputy and Council to King Henry VIII.

[xlviii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 455-6. CCCXC. The Lord Deputy and Council to King Henry VIII.

[xlix] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 472.

[l] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, pp. 473-4.

[li] The Earl’s heir was his legitimate son Richard, a minor at the time of his father’s death, but Thomas was older and active politically at the time of Ulick na gCeann’s death.

[lii] J. Morrin (ed.), Calendar of the Patent and Close Rolls of Chancery of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, Vol. I, Dublin, Alex, Thom & sons, 1861, p. 87.

[liii] Connors, T.G., Surviving the Reformation in Ireland (1534-80): Christopher Bodkin, Archbishop of Tuam,and Roland Burke, Bishop of Clonfert, The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 32, No. 2 (Summer, 2001), pp. 335-355; Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, 1834, p. 463-5, CCCXCIII. An Abregement of the Irisshmens Requestes.

[liv] Morrin, J. (ed.), Calendar of the Patent and Close Rolls of Chancery of the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, Vol. I, Dublin, Alex, Thom & sons, 1861, p. 87.

[lv] Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters. 1542. No. 21.

[lvi] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 491, Lord Justice and Council to Sentleger.

[lvii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 491, Lord Justice and Council to Sentleger.

[lviii] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 491, Lord Justice and Council to Sentleger.

[lix] Correspondence between the Governments of England and Ireland 1538-1546, State Papers published under the authority of His Majesty’s Commission, Henry VIII, Part III, 1834, p. 491, Lord Justice and Council to Sentleger.