Frustrated with a vigorous mind trapped within an aging body, the poet W.B. Yeats climbed to the top of his tower in County Galway, and, ‘under the day’s declining beam’ stared out over the surrounding countryside. From the height of his tower’s battlements the landscape resonated with images and memories from his and the region’s past, images he brought to life in his 1926 poem ‘the Tower.’

Among the first images he conjured up, as he gazed across the treetops and the undulating stone-walled fields, was that of the gift of a pair of ears, bestowed upon one Mrs. French, the lady of a nearby Big House.

‘Beyond that ridge lived Mrs. French, and once

When every silver candlestick or sconce

Lit up the dark mahogany and the wine,

A serving-man, that could divine

That most respected lady’s every wish,

Ran and with the garden shears

Clipped an insolent farmer’s ears

And brought them in a little covered dish.’

The folklore, people and places of County Galway and in particular of the area about Thoor Ballylee, Yeats’ late medieval tower-house near Gort in the south west of the county, provided the poet with a large repository of imagery and symbolism for his work. His reference here to Mrs. French and her serving man’s unusual gift derived, not from fiction but from a true story that resulted in a celebrated eighteenth century court case.

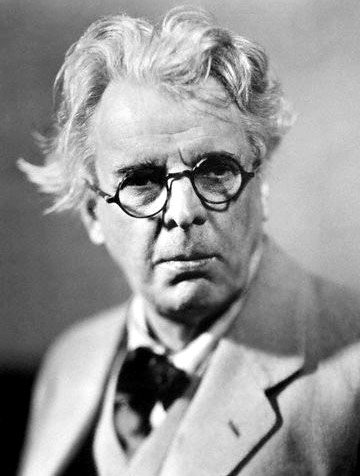

The poet William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), who first visited the area about Ballylee, Peterswell and Gort in 1896 on a walking tour of the West of Ireland.

Ballylee Castle, given the name ‘Thoor Ballylee’ by Yeats, who purchased the tower and its associated buildings over the winter of 1916 and came to take possession in the summer of 1917. Over time he restored the tower house to the design of Professor William A. Scott and his family resided there throughout much of the 1920s, departing in 1929.

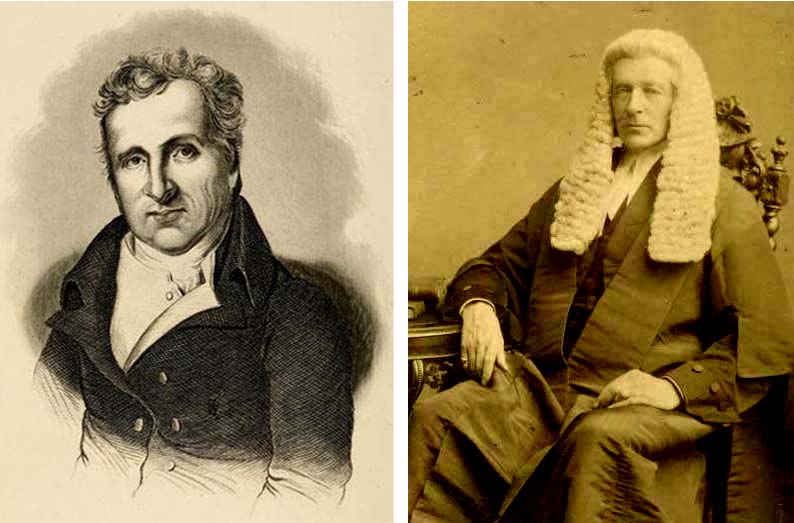

Before Yeats’ time the story of Mrs. French and the farmer’s ears was included in a publication entitled ‘Anecdotes of the Connaught Circuit,’ written in 1885 by Oliver Joseph Burke, scion of an ancient branch of the Burkes seated at Ower, near Headford in County Galway, Papal Knight, Barrister-at-Law, author and, one would assume from his store of stories, a proficient raconteur. In recounting the details of this story Burke drew heavily upon the recollections of Sir Jonah Barrington, M.P., whose memoir ‘Personal Sketches in his own times’ was first published in 1827. Barrington not only lived closer to the time of these events but was in fact the grandson of this Mrs. French.

Sir Jonah Barrington M.P., grandson of Mrs. French (left) and Oliver J. Burke KSG of Ower, Headford, County Galway (right)

Born in 1760, Barrington was the fourth of sixteen children of John Barrington of Knapton, County Laois (then called Queen’s County). His mother, however, was the daughter of Patrick French of Peterswell in County Galway, Barrister-at-Law, where, his grandson related, he held ‘large estates.’ French’s wife, Catherine, the subject of Yeats’ poem, was described by her grandson Barrington as ‘one of the last remaining of the first house of the ancient O Briens.’ The fourth daughter of Henry O Brien of Stonehall in County Clare and granddaughter of Sir Donatus of Dromoland, she married Patrick French in 1727. Her brother Donatus O Brien, who succeeded to the O Brien family estates, had emigrated to England and died at his house in that country, ‘leaving his great hereditary estates in both countries to the enjoyment of his mistress, excluding his family’ Barrington noted with disdain ‘from all claims upon the manors and demesnes of their ancestors.’

Barrington cited the story of his grandmother and the insolent farmer’s ears, to which Yeats referred, as evidence of what he regarded as the ‘extraordinary devotion of the lower to the higher orders in Ireland in former times,’ although he did add somewhat bitterly that, by his own time, this had changed and this change could be evidenced he claimed, in his own words ‘by the propensity servants now have to rob (and, if convenient, murder) the families from whom they derive their daily bread.’

It’s worth giving Barrington’s own account of this story and so I quote below directly from his ‘Personal Sketches,’ written for his amusement to while away the cold winter evenings.

‘My grandfather, Mr. French of County Galway, was a remarkably small, nice little man, but of an extremely irritable temperament, an excellent swordsman, and, like all Galway gentlemen, proud to excess.’

‘My grandfather had conceived a contempt for, and antipathy to, a sturdy half-mounted gentleman, one Mr. Dennis Bodkin, who entertained an equal aversion to the arrogance of my grandfather, and took every possible opportunity of irritating and opposing him.’

‘My grandmother, an O Brien, was high and proud, steady and sensible, but disposed to be rather violent at times in her contempts and animosities, and entirely agreed with her husband in his detestation of Mr. Dennis Bodkin.’

‘On some occasion or other Mr. Dennis had chagrined the squire and his lady most outrageously. A large company dined at my grandfather’s, and my grandmother concluded her abuse of Dennis with an energetic expression that could not have been literally meant, in these words, – “I wish the fellow’s ears were cut off! That might quiet him.”

‘This passed over as usual: the subject was changed and all went on comfortably till supper; at which time, when everybody was in full glee, the old butler, Ned Regan, who had drunk enough, came in – joy was in his eye – and whispering something to his mistress which she did not comprehend, he put a large snuff box into her hand. Fancying it was some whim of her old domestic, she opened the box and shook out its contents; when, lo! a considerable portion of a pair of bloody ears dropped on the table! Nothing could surpass the horror and surprise of the company. Old Ned exclaimed, – “Sure, my lady, you wished that Dennis Bodkin’s ears were cut off; so I told old Gahagan (the gamekeeper), and he took a few boys with him, and brought back Dennis Bodkin’s ears – and there they are; and I hope you are plazed my lady!”

In the words of Barrington, ‘the sportsman (ie. the gamekeeper) and the boys were ordered to get off as fast as they could; but my grandfather and grandmother were held to heavy bail and were tried at the ensuing assizes at Galway. The evidence of the entire company, however, united in proving that my grandmother never had any idea of any such order, and that it was a mistake on the part of the servants. They were, of course, acquitted. The sportsman never reappeared in the county till after the death of Dennis Bodkin, which took place three years subsequently.’

This court case appears to have taken place about 1778, which would place the year of Bodkin’s death about 1781.

It would appear to have had all the hallmarks of a local cause célèbre in the late eighteenth century. As generations passed it provided the makings of a warm fireside tale on a cold winter’s evening among the diminishing few in the locality who would recall the story. Barrington’s and Burke’s books ensured its survival in print but Yeats’ inclusion of the butler’s gift to Mrs. French as a part of his rich poetic imagery elevated the story from an obscure local eccentricity to become, in some small way, a miniature part of the rich poetic treasury of the country.

‘An ancient bridge, and a more ancient tower, / A farmhouse that is sheltered by its wall, / An acre of stony ground, / Where the symbolic rose can break in flower, / Old ragged elms, old thorns innumerable.’

Thoor Ballylee, ‘under the day’s declining beam.’

The tower and cottage fell into disuse and ruin after the departure of the Yeats family. Described in the early 1950s as ‘a barn for cattle and a rallying place for crows,’ it was restored and opened to the public as a museum, tea room and shop in 1965, the centenary year of the poet’s birth. Closed after it was extensively damaged as a result of severe flooding in the winter of 2009, negotiations were still on-going in November of 2013 with a view to having Yeat’s tower re-opened to the public.

Comments are closed.