© Donal G. Burke 2013

By tradition said to descend from William, father of Richard the Anglo-Norman conqueror of Connacht and grandfather of Walter, Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht, the name Burke occurs in medieval Latin documentation as de Burgo. The name was written in other contemporary documents as de Burgh. It would appear, however, that the name may not have been pronounced with a soft ending later associated with its pronunciation in England. Letters written as early as 1327 in the Anglo-French language of the day relating to the most prominent members of the family in Ireland give the name as ‘de Bourk.’[i] This would suggest a close link with how the name sounded to the contemporary Irish who wrote the name ‘a Búrc’ or ‘de Búrc.’[ii] Based on the phonetics of the Anglo-Norman name in everyday use in medieval Ireland the name de Burgh became Burke or Bourke in that country, with the exception of a small few who in later generations reverted to the former.

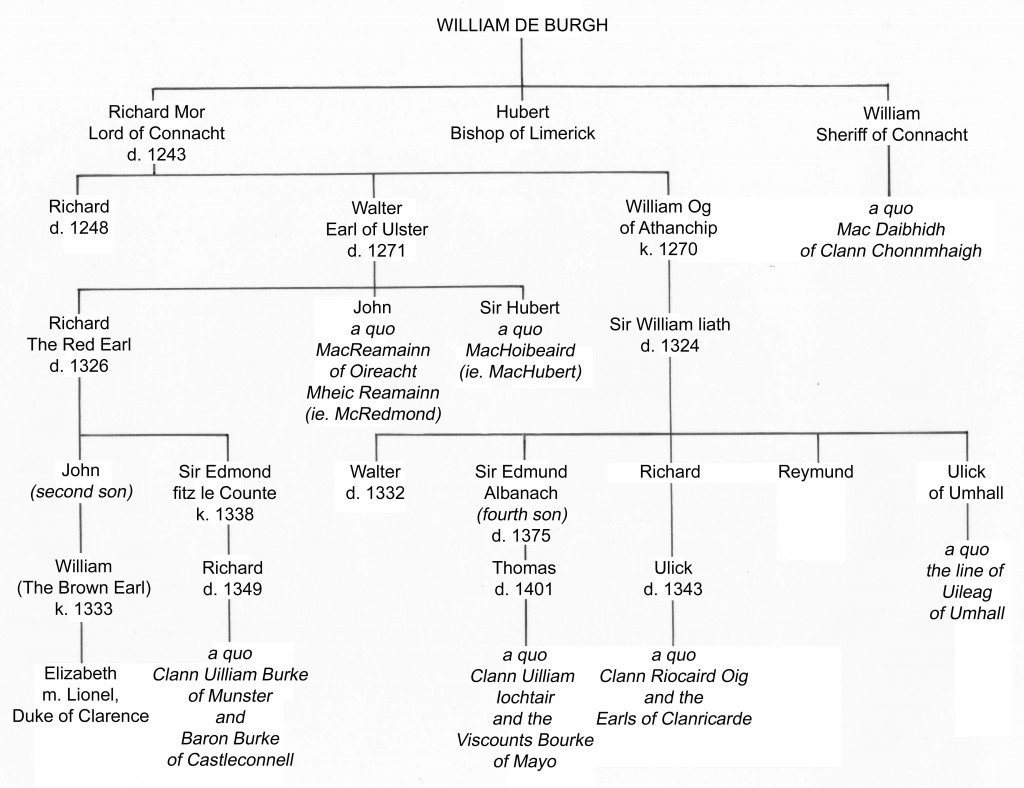

Clanricarde, as its name in the Irish language, the ‘Clann Riocaird’ or ‘family of Richard,’ suggests, in its original manifestation referred to the nearest kinsmen of Richard de Burgh, the Red Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht who died in 1326. Over the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth century the name came to be appropriated by a different family of the de Burghs or Burkes, the descendants of the Red Earl’s cousin Sir William liath de Burgh, who died in 1324.

The branch of the de Burghs or Burke who came to prominence in the fourteenth century as the chieftains of Clanricarde, a territory covering much of east Galway in southern Connacht, descended from Sir William liath ‘the grey-haired’, a close kinsman of Richard de Burgh, the Red Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht.

Non-exhaustive pedigree table showing selected branches of the Burkes. H.T. Knox gives an alternative line of descent for the chieftains and Earls of Clanricarde.

Sir William liath de Burgh

Sir William liath de Burgh was a powerful figure in the de Burgh lordship of Connacht. His name rendered also in certain Latin documentation as William canus de Burgo or ‘the white or grey-haired,’ William was the son of the Red Earl’s uncle Sir William óg de Burgh who had been executed in captivity by O Connor at the battle of Athanchip in 1270.[iii] While the head of the family, as Earl of Ulster, ruled a vast territory that extended across part of Munster, the lordship of Connacht and over Ulster, Sir William appears to have been pre-eminent in acting in the Earl’s interests within Connacht. His wife was given as ‘Fymiola iuyn ybrisen ruais’ or Finnoula daughter of O Brien roe (O Brien the red-haired).[iv]

His lifespan appears to have mirrored that of the Red Earl closely and they appear to have been of a similar age, the Red Earl coming into possession of his estates about 1280.

When John FitzThomas FitzGerald acquired through his wife large estates in Northern Connacht he pursued policies that put him at odds with the Red Earl. Disputes between the two resulted in FitzThomas capturing both the Earl and William liath in 1294 and holding them captive for over three months, throwing Connacht into chaos. Both de Burghs were released by order of parliament and, while a truce was later agreed and FitzThomas was required to deliver himself to the Earl’s prison for a time. The dispute eventually resulted in FitzThomas, for his part, surrendering his Connacht lands that were acquired by the Earl, thus diminishing the power in the north-west of a rival Anglo-Norman house.[v]

In 1296 William de Burgh intervened in the affairs of the O Connors alongside the Earl’s brother Theobald to bolster the position of Aedh son of Eoghan O Connor, the king of the Irish of Connacht, who had been deposed by internal rivals. On that occasion they forced the rebellious chieftains to submit and had then brought to the Red Earl’s residence to make peace with Aedh son of Eoghan.[vi]

Sir William liath served alongside the Red Earl fighting for the king in the Scottish war in 1303. In recognition of his good service in Scotland the king gave Sir William the custody of the Kerylochnarney lands of Thomas FitzMaurice of Desmond’s heir until he should come of age.[vii]

By 1307 Sir William liath was a significant figure in Ireland and was appointed by the King Deputy Justiciar of Ireland for half a year, during the vacancy of the office of justiciary.[viii] In that role he was obliged to keep about him at all times 20 men-at-arms and in October 1308 he was in the process of gathering another 200 hobelers and 500 foot soldiers which he was about to lead ‘into the Leinster mountains to attack the Irish felons there.’[ix] The armed force that de Burgh brought into Leinster on the King’s behalf included not only such Anglo-Normans of Connacht as Hugo de Burgh, Thomas Dolphin, Geoffrey de Valle, Stephen d’Exeter, Phillip Haket, David Cosyn and Richard le Blake but some of the most senior Gaelic chieftains within the de Burgh lordship, many from about the area of east Galway or Roscommon, such as Rory O Connor, Tadhg O Kelly, ‘Odoni’ son of Donagh O Kelly, Maine O Kelly, John son of Simon and ‘Thomultagh’ O Kelly, John Offallowyn (O Fallon) and John or Eoghan O Madden.[x]

Intervention in the selection of the O Connor king

The responsibility with which Sir William liath was entrusted by the Earl was evidenced in the central role he played in the politics of the O Connor kingship at this time. When Aedh son of Eoghan, the O Connor king, was killed in 1309 by his rival Aedh breifneach O Connor, MacDermot, King of Moylurg came to support his foster son Felim O Connor as king and called on the support of his allies, both Gaelic and Anglo-Norman. William liath and his kinsmen came to their aid and all arrived ‘into the heart of Silmurray’ in O Connor’s territory.’ Together they moved to keep the local chieftains from consenting to the kingship of Aedh breifneach. By show of force MacDermott and his allies compelled the Gaelic leaders of Sil Murray to agree to no king other than their candidate Felim.[xi]

Another of the family, Rory, brother of Aedh breifneach, killed de Bermingham not long thereafter. On the calling of a truce it was Sir William liath who attended a meeting with the same Rory that ended with the killing of a number of Rory’s supporters and after a brief campaign the ejection of Rory by Sir William liath.[xii]

In 1310 Aedh briefneach led a devastating raid into MacDermott’s country and Sir William liath immediately marched against him. Aedh breifneach covertly had his brother Rory and his supporters to take the castle (Buninna) that Sir William liath had just left and while Sir William liath was encamped opposing Aedh breifneach, the castle was plundered.

Sir William liath, however, had previously held secret discussion with one Seonacc MacQillin, the leader of a mercenary band hired by Aedh breifneach and billeted about him. De Burgh had promised to reward MacQillin should he kill O Connor. McQuillin, seeing his opportunity with so many of O Connors followers plundering the castle, thereupon slew Aedh breifneach with a short-handeled axe.[xiii]

As soon as Sir William liath learned of O Connors death, he along with his ally MacDermot and his people launched an attack on Aed breifneachs supporters and sent out foraging parties in all directions. He then returned to the heart of the Sil Murray lands and billeted two hundred of MacQullins mercenaries in quarters about the territory. The Irish annalists record the impact of Sir William’s liath’s victory, stating that ‘there was not one townland in Sil Murray without its permanent quartering, not a tuath free from exaction, not a prince free from oppression, so long as William Burke was in control over them after the death of Aedh.’[xiv]

The heavy impositions placed upon McDermott people and territory rankled with McDermott, whose power Sir William liath strove to reduce and thereby held keep a tighter control of the territory and led McDermott to carry his foster son Felim O Connor to the ancient inauguration site at Carnfree and have him inaugurated as king.

Lands of Sir William de Burgh

Sir William liath, among his other landed interests, appears to have leased lands of Sil Murray in Connacht from the King at this time. He was allowed half of his debts due to the King for lands in ‘Shilmurthy’ in 1310 as a reward ‘for his various outlay and expenses and the great diligence that (he) sustained in guarding with an armed force the King’s men and lands in the parts of Roscommon that Eoth Bretnagh (Aedh Breifneach) son of Cathel Roth (ruadh) O Concghur, wished to kill and destroy.’ William, the Justiciar acknowledged, ‘with his armed force, bravely thwarted Eoth, who wished to make himself king of the Irish of Connacht against the King’s will and that of the King’s ministers, and later killed Eoth, the King’s felon.’[xv]

The location of the principal estate or estates of Sir William liath is uncertain.[xvi] The descendants of a number of his eldest sons held lands about northern Connacht which would suggest that he may have held large interests there at one time and about Lough Mask and possibly the western bank of Lough Corrib in western Connacht.[xvii] His property was likely to have been extensive and does not appear to have been confined to one location.

He appears have also acquired an interest in lands in the cantred of Sil Anmchadha in east Galway also, entering into an agreement in 1308 with Sir Edmund Butler (who also held the lands about Aughrim) whereby de Burgh assured O Madden of his lease of ‘the land of Lusmauth’ which he had from the same Sir Edmund ‘unless by law or right he shall be expelled from the lease so granted him by Sir Edmund or Sir William.’ He does not, however, appear to have acquired property on an extensive scale in the eastern region of what would later be County Galway.

Intervention in the affairs of Thomond

Sir William liath lost two sons in 1311, both of whom were likely to have been among his elder sons, when they were killed by the sons of certain of the Gaelic kings of Leinster.[xviii] He intervened in the wars of Thomond, south of Connacht in Munster about May of that same year in support of one O Brien candidate for the kingship of that territory over another. His intervention placed him at odds with the Anglo-Norman Richard de Clare, who supported a rival O Brien for the kingship. In battle near Bunratty, Sir William liath defeated de Clare but, with few attendants about him, de Burgh was taken captive. Among the dead was his standard-bearer Sir John Crok.[xix] De Burgh’s candidate was then killed and de Clare’s candidate installed as king of Thomond.

De Clare, not long after taking him captive, released de Burgh on condition that he would fulfil a number of conditions and having extracted a guarantee from him that he would abstain from intervening in the affairs of Thomond. The Irish annals record that ‘he did not, however, fulfil the conditions or keep his word as a knight, but came into Thomond with a more numerous army to make war on de Clare’ and his O Brien and to obtain the kingship of that territory for a new O Brien candidate of his own. He proceeded to drive de Clare’s O Brien out, took hostages from the leading men of Thomond and brought them back with him into Connacht, leaving his favoured candidate Muirchertach O Brien as king of Thomond.[xx]

Muirchertach appears to have had a short time as king before being pushed back into Connacht as de Clare’s man, Dermot clereach O Brien was called King of Munster (or Thomond) at his death in 1313. On his death Muirchertach again invaded Thomond to gain the kingship. De Clare threw his support behind an opposing candidate, one Donagh O Brien and, although he initially gained the upper hand, lost it for a short time before pushing Muirchartach back again into Connacht.

Edward Bruce in Ireland

In 1315 Edward Bruce, brother of the Scottish king, Robert Bruce, landed in Ulster, and many of the native Irish flocked to his banner. The Red Earl gathered a great force of his Anglo-Norman and Gaelic allies and vassals at Roscommon, including Felim O Connor King of Connacht and marched to engage Bruce. Sir William liath was with the Earl in the campaign, leading a small party who sought to catch Bruce by surprise about Louth.

Bruce covertly induced Felim O Connor to leave the Earl’s forces while Felim’s rival Rory, brother of Aedh breifneach, seeing so many of his rivals supporters out of Connacht at the time saw an opportunity to make a grab for power. Rory also held negotiations with Bruce and offered to push the Anglo-Normans out of Connacht, to which Bruce agreed with the proviso that Rory not trespass or plunder the lands of Felim.

Rory, however, while Felim was still with the Earl, gathered his allies and mercenaries and struck deep into Sil Murray and on into the rest of Connacht, burning all in his path including Dunamon, Roscommon, Rinndown and Athlone and had himself proclaimed king at the traditional site of Carnfree. Felim and his men left the Earl’s army on learning of Rory’s actions but found himself unable to oust Rory.

When Felim’s men left the Earl’s camp, the Red Earl’s forces were obliged to retreat to the castle of Connor, where they suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of Bruce in September 1315. In the battle of Connor, O Neill and the Irish of Ulster, together with the Scots, took the Earl’s forces by surprise and, while several prominent Scots knights fell, the Scots won the field. Sir William liath de Burgh was wounded and taken prisoner and an account written a month later reported that he was ‘said to have been sent to Scotland.’[xxi]

The Earl repaired to Connacht, which was thrown into turmoil as the O Connors took full advantage of the situation and where the Irish swept across the lordship devastating Anglo-Norman settlements including Aughrim and Dunmore.[xxii] Tadhg O Kelly burned and plundered the Earl’s own cantred of Maenmagh about Loughrea, while the Earl, rendered politically and militarily impotent following his defeat and bereft of support, was left ‘a wanderer up and down Ireland all this year with no power or lordship’[xxiii] To him repaired a number of Gaelic chieftains who had previously been loyal, such as Eoghan O Madden of Sil Anmchadha, who were now ousted by their rivals who supported Felim.

The following year Felim assembled a large force of his own supporters, including his MacDermott foster-father, de Bermingham and seized the kingship, plunders Rory’s supporters and took hostages of the O Kellys, O Maddens and other chieftains of Connacht. He then turned on the Anglo-Normans of west Connacht, killing a number of the leading knights of that territory. Having imposed his will on north Connacht he made for the Anglo-Norman castle of Meelick on the Shannon in east Galway. There he met with more of his allies and burned and broke down the castle and made for Roscommon to destroy that settlement.[xxiv]

The ranson of Sir William liath

The Red Earl found himself at a loss to adequately respond to the depredations of the Irish across Connacht and Ulster at a time when, in the Summer of 1316, Edward Bruce was inaugurated as High King of Ireland by his Irish followers. The Earl negotiated a ransom with the Scots for the return of Sir William liath. He was a valuable hostage and the Earl took it upon himself to divert eight supply shops intended for the defence of Carrickfergus Castle in Ulster to provide the ransom required to free his kinsman in Scotland.[xxv]

After about ten months in captivity, Sir William liath was back in Ireland by the summer of 1316 and made for Connacht with a band of soldiers led also by de Bermingham and other Anglo-Normans of Connacht. His arrival was recorded as significant by the annalists, who say that Felim immediately called upon his subjects to expel de Burgh and assembled for that purpose a large army across the region between Assaroe and Sliabh Aughty. The strength of the army assembled by Felim may be gauged from the presence of his O Brien allies from Thomond in Munster, the king of the Irish of Meath and the king of the Irish of Breffni in addition a wide array of O Connor’s own Irish followers across Conncht such as the O Kellys of Ui Maine.[xxvi]

The battle of Athenry 1316

Felim marched to de Bermingham’s town of Athenry in east Galway to oppose the Anglo-Norman force. The two armies met in front of the town on the 10th of August 1316 and in the ensuing battle Felim O Connor was killed. The defeat was a heavy blow to the Irish of Connacht, in which Tadhg O Kelly, chief of Ui Maine together with twenty-eight of the ruling house of the O Kellys were killed. Members of almost every ruling house of the Irish in Connacht lost leading individuals. Of those of east Galway, other than the O Kellys, who lost leaders were rebels of the O Maddens, O Concannon and others, including MacEgan, O Connor’s brehon.[xxvii]

It was Sir William liath who took the first steps in re-establishing de Burgh dominance in Connacht in the wake of the battle of Athenry. With the Gaelic forces of those opposed to the de Burgh’s spent in Connacht, he brought a large force into Sil Murray and imposed his will on the surviving O Connors and their allies. The victory at Athenry was such that it was said the victors were able to significantly add to the walled defences of the town from the profits derived from the weapons and equipment of the defeated dead.

A new pliant O Connor King was set up by the de Burghs in Connacht but in Ulster Edward Bruce still maintained a dominant position, holding court in the Red Earl’s former castle of Carrickfergus. Having sought the practical support of his brother from Scotland he took to the field again in 1317 but achieved little of lasting significance. He and his brother Robert were confronted by the Red Earl in Leinster but the Earl was forced to retreat to Dublin, where he was followed by the Scots. Doubts persisted concerning the Red Earls determination to oppose the Bruce brothers and the mayor of that town, fearing that the Earl would surrender the town to Bruce, imprisoned the Earl in Dublin Castle. The Scots, however, lacking the necessary provisions for a siege, withdrew and continued into Munster, returning later to Ulster. Richard de Burgh languished in the Dublin prison for four months before he was released in June by the Kings order under humiliating conditions.

The following year Edward Bruce launched another campaign south but was defeated and killed at Faughart near Dundalk. His invasion coincided with successive years of famine and disastrous weather in Ireland. Combined with the widespread destruction of crops and property caused by the wars, the invasion left the lands of much of the Anglo-Norman lordship of Ireland waste and further depleted of colonist tenants on the ground for some time thereafter.

The Red Earl, back in power after the final defeat of Bruce, set about attempting to restore his authority across his lands. Sir William liath continued, under the Earl, in the capacity as the principal actor in the de Burgh interest in Connacht until his death. The O Connor set up by Sir William after the battle of Athenry was killed later that year and one Turlough O Connor seized the kingship in 1317. Turlough it would appear, however, received the acknowledgment and support of the Crown’s representative in Ireland, Edmund Mortimer. A rival, Cathal son of Donal O Connor, opposed him and repulsing an attack made on him by Turlough, defeated him and seized the kingship for himself. He then appears to have placed himself under the protection of Sir William liath and the Anglo-Normans of Connacht. He would remain king until the year of Sir William de Burgh’s death, in which year he would be killed and replaced by Turlough.[xxviii]

The support of various Religious Houses

Like others of the most prominent landholders in that period, many concerned for the salvation of their souls given the violence endemic in their lives, Sir William liath allocated funds towards the foundation or support of religious houses. To him was attributed the foundation in 1296 of the Franciscan friary on an island at the town of Galway.[xxix]

Both William liath and his wife Finnoula were generous benefactors to the Dominican friars at Athenry, where the Earl’s chief tenant in Connacht, de Bermingham, had founded a friary in 1241. William liath and his wife gave the friars the tithes of all their farms or granges and bestowed more than one hundred marks to the foundation to facilitate works to the ‘front’ of their church and for the provision of glass to the same. De Burgh’s funds paid for the enlargement of the choir by six metres in the easternmost end of the church and in the presbytery, the space within that choir before the high altar, de Burgh made provision for a burial place for himself, his wife and family.[xxx]

Sir William liath died on the 12th February 1324.[xxxi] Prior to William liath’s burial arrangements at Athenry, the customary burial place of the de Burghs was in the Augustinian monastery of the Canons Regular of Athassel in Tipperary. While the Red Earl would be buried after his death in 1326 at Athassel, William liath, upon his death, was interred at his honoured burial place in the Church of SS. Peter and Paul at the Athenry friary. Both he and his wife Fionnuala were buried ‘in the rank of deacon.’[xxxii] Thereafter the Dominican foundation at Athenry would serve as the burial place for many of William liath’s descendants. (Thomas de Burgh, son of the Earl of Ulster, died in the house of the friars at Athenry and was also buried in the monastery church at Athenry, near the high or great altar, but it is unclear if he was buried before or after William liath.[xxxiii] One transcription of the Registry of Athenry describes him as son of the Red Earl and as having died in 1316.)[xxxiv]

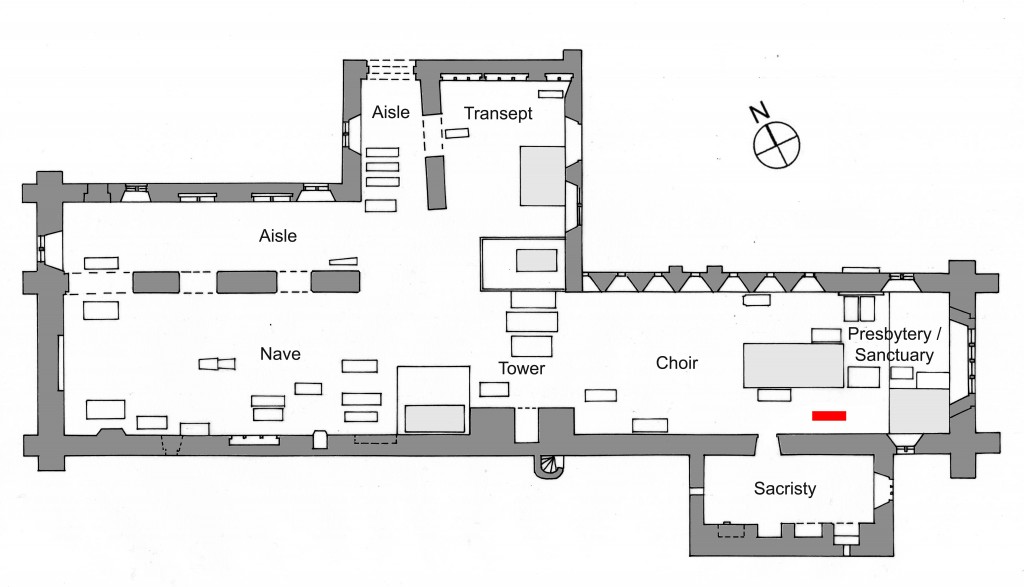

The burial place of Sir William liath de Burgh

Any grave-slab placed over Sir William and his wife was, in all likelihood, disturbed in the destruction that the church witnessed over succeeding centuries but the location of his burial place may be gauged from the written description of burials in the Registry of the friary. While the burial place of the founder de Bermingham would have occupied a high status burial location in the choir as it originally stood, de Burgh’s burial place in the presbytery would also have been of high status. The presbytery, that area reserved for the clergy in the easternmost area of the nave, was included in that part of the church extended by de Burgh. William liath’s burial place may be gauged from the description of later burials. ‘MacMeyler dubh,’ a later de Burgh or Burke, was buried between the corner of the altar and the piscina, between the church gable (east) and the feet of William liath. As the piscina was commonly located to the south of the altar, William liath may have been buried on the southern side of the presbytery, between the centre of the presbytery and the south wall, as one Henry de Burgh, his posterity, including his son Edmund, were buried between the head of William liath and the entrance doorway to the sacristy.[xxxv] The sacristy was constructed against the south wall of the chancel or choir. He may have lain in the general vicinity of a much later defaced Burke graveslab dating from 1793, possibly between it and the wall of the sacristy.

Approximate location of the burial place of Sir William liath de Burgh (in red colour) at the Dominican friary, Athenry. (Plan of Church of SS. Peter and Paul after R.A.S. Macalister.)

Walter son of Sir William liath de Burgh

On the death of the Red Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht in 1326 his heir was still a minor. The Red Earl’s two eldest sons, Walter and John, had died during their father’s lifetime and the heir to the Red Earl’s vast lordship of Connacht and Ulster was his underage grandson William de Burgh.

Advice given to the heir’s mother Elizabeth de Burgh in the year following the Red Earl’s death regarding the lordship estates listed what would appear to have been the six most important members of the family in Ireland. Foremost among the six was the Red Earl’s eldest surviving son Edmond, identified as Edmond fitz le Counte (i.e. Edmond son of the Count) whose lands lay about Castleconnell in Munster.[xxxvi] The next was given as Walter de Burgh, who was listed with two of his brothers; ‘Edmond le cousin’ and Richard. After Walter in prominence appears to have been one Richard de Burgh le hore (‘the grey’) and one Hubert de Burgh.[xxxvii] The property of these six individuals lay across Connacht and Munster but none were established in Ulster.

Given the prominent position ascribed to this Walter de Burgh in 1327, he appears to be Walter, the eldest son of Sir William liath. During the minority of the Red Earl’s heir, this Sir Walter de Burgh established himself as a powerful figure within the de Burgh lordship. Together with Edmond fitz le Counte he was appointed one of the two Justices of the Peace or governors of the counties of Connacht, Limerick and Tipperary during the minority of the heir.[xxxviii] William, the Red Earls’ heir, came of age and took control of his lands in the autumn of 1328 but Walter pursued his own vigorous policies that in certain areas were directly opposed to those pursued by the young Earl.

Walter de Burgh was a generation older than the Earl and, while occasionally supporting the Earl, continued to assert his own schemes independent of the Earl, harrying Turlough O Connor of Connacht, who had the recognition of the King of England and the support of the young Earl and the Earl’s uncle Edmond fitz le Counte. Walter blatantly opposed the Earl against O Connor and in 1330, while he and his allies were fighting O Connor, one account by the Irish annalists of his actions claimed that ‘the forces of all Connacht, both foreigner and Irish, were collected by (Sir Walter) after this to seize the kingship of Connacht for himself.’[xxxix] While nothing lasting came of Walter’s plans at this time, some credence was given by a number of his contemporaries to the possibility that he conspired to make himself ruler of Connacht independent of the Earl of Ulster. This is corroborated in his being named alongside Maurice Earl of Desmond in Munster, Sir William de Bermingham (brother of the Earl of Louth), Brian O Brien and MacNamara of Thomond and others as party to a conspiracy to have the unruly Desmond advanced to a position of power over all of Ireland, with Walter left in control of Connacht.[xl] Walter and the other alleged conspirators were indicted by jury and it may have been as a result of this indictment, in addition to his difficult relationship with the Earl of Ulster, that the young Earl had Edmond fitz le Counte take Walter and his brothers Edmond Albanach ‘the Scotsman’ and Reymond de Burgh captive in November of 1331.[xli]

Desmond and one Henry de Mandeville of Ulster, another alleged conspirator, were taken captive also in 1331, as was Sir William de Bermingham in the following year. While Desmond, de Mandeville and de Bermingham were held at Dublin Castle, Walter de Burgh was taken to the Earl of Ulster’s castle of Northburgh in Ulster and reputedly allowed to starve to death in 1332. Walter’s body was thereafter brought back to Connacht and buried alongside that of his father in the presbytery (the chancel or ‘sanctuary’) of the church of SS. Peter and Paul at the Dominican friary of Athenry.[xlii]

It has been suggested that such a conspiracy involving individuals often violently at odds with one another was unlikely. However, a number of the most prominent Anglo-Norman suspects had been incarcerated as a result and while Desmond and de Mandeville were later released and Walter de Burgh died in captivity, de Bermingham was hanged in July of 1332.[xliii]

Murder of the Brown Earl of Ulster

In retaliation for the death of Walter, his sister Gyle, who was married to Sir Richard de Mandeville, one of the Earl’s chief Anglo-Norman tenants in Ulster, connived with members of her husband’s family and a number of others, to avenge her brother and in 1333 the conspirators had the twenty-one year old Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht murdered.

The murder of the Earl caused havoc across the Earl’s territories and came as a devastating blow to the Anglo-Norman colony in Ireland. William, known to the Irish annalists as William ‘donn,’ or The Brown Earl, had no son but three surviving daughters, his heiresses, who were soon after taken by their mother to England.[xliv] A bitter interfamilial feud broke out among the de Burghs. Several powerful junior branches of the de Burgh family were well established in Connacht, and these went to war with the dead earl’s uncle, Sir Edmond fitz le Counte de Burgh, who was given a lease of the Connacht lands during the minority of the Brown Earls daughters. With the sudden loss of the Earl without a male heir and infighting among the leading members of the family, the principal lordship in Ireland began to crumble. In Ulster and Connacht many of the native Irish formerly under the control of the de Burghs broke free of the Crown and in the turmoil that followed began to regain lost ground.

Continued under ‘Burke 1334 to 1387.’

[i] Sayles, G.O. (ed.), Documents on the Affairs of Ireland before the King’s Council, Dublin, I.M.C., 1979, pp. 126-7. No. 155. ‘The advice tendered to Elizabeth de Burgh by her council in Ireland 1327.’

[ii] The use of the spelling ‘de Búrca’ is a relatively modern introduction, the name more often written in older Gaelic language documents as ‘a Búrc’ or ‘de Búrc.’

[iii] De Burgo, T., Hibernia Dominicana, Rome, Metternich, 1762, p. 224. From a transcription of the Registry of Athenry, attested as an accurate copy by Matthew Ward, Malachy Brehony and Constantine Brehony, 1619. ‘obitus Domini Gulielmi Athankip de Burgo, dicti Gulielmi Magni, Anno Domini 1270. Obitus Domini Gulielmi Cani de Burgo, praedicti Gulielmi Magni filii, Anno 1324.’ The Annals of Connacht, in its obituary of Sir William liath, refer to him as ‘Uilliam liath mac Uilliam moir,’ ie., William liath son of William the great, which would correspond to the latin description of his father in the Athenry Register as ‘Gulielmus magnus.’ (Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), p. 257.) His father was also referred to as William óg or William the younger. The British Museum copy of the Athenry Register does not carry the death record of William of Athanchip and while it gives that of William liath, it does not state the name of his father.

[iv] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, p. 212.

[v] Knox, H.T., The History of the County of Mayo to the close of the sixteenth century, Dublin, Hodges, Figgis & Co., Ltd., 1908, pp. 122-3.

[vi] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 195-7.

[vii] Knox, H.T., The History of the County of Mayo to the close of the sixteenth century, Dublin, Hodges, Figgis & Co., Ltd., 1908, p. 123.

[viii] Knox, H.T., The History of the County of Mayo to the close of the sixteenth century, Dublin, Hodges, Figgis & Co., Ltd., 1908, p. 123.

[ix] Calendar Patent Rolls Chancery Ireland, 2 Edward II, 18th October 1308.

[x] Connolly, P., An Account of Military Expenditure in Leinster, 1308, Analecta Hibernica, No. 30, 1982, pp. 1, 3-5.

[xi] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 217-225.

[xii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 217-225.

[xiii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 217-225, 227. Seonac McQuillin, after killing one identified as ‘an Gruelach’ at Ballintubber in Roscommon in 1311, was killed immediately thereafter in retaliation. The Irish annalist recounting the killing of McQuillin, recounted that it was with the same short-handled axe that he used to kill Aedh breifneach O Connor that McQuillin was killed.

[xiv] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 217-225.

[xv] Calendar Patent Rolls Chancery Ireland, 4 Edward II, 25th July 1310. William liath was described in this contemporary account as ‘William son of William Burgh.’

[xvi] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 33, No. 2, 1903, pp. 183-6.

[xvii] Knox, H.T., Occupation of Connaught by the Anglo-Normans after A.D. 1237 (Continued) J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 33, No. 2, 1903, pp. 183-6. His eldest son Walter was described as of the diocese of Annaghdown, about Lough Corrib.

[xviii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), p. 225.

[xix] Annals of Inisfallen, 1311. No. 4. ‘agus do marbad ann fod Sira Seoan de Cruac, fear brataighi in Burcaid.’

[xx] Annals of Inisfallen, 1311.

[xxi] Phillips, J.R.S., Documents on the early stages of the Bruce Invasion of Ireland 1315-1316, Proceedings of the R.I.A., Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, Vol. 79, 1979, pp. 263-4. Account of John le Poer of Dunoyl, dated Dunoyl, 3 October 1315.

[xxii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), p. 241.

[xxiii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), p. 241.

[xxiv] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 243-9.

[xxv] McNamee, C., The Wars of the Bruces, Scotland, England and Ireland, 1306-1328, East Linton, Tuckwell Press Ltd., 1997, p. 180.

[xxvi] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 243-9.

[xxvii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 243-9.

[xxviii] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), p. 259.

[xxix] Jennings, B., The Abbey of St. Francis, Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 22, Nos. 3 & 4, 1947, p. 101.

[xxx] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, p. 212.

[xxxi] Blake, M.J., Notes on the Persons Named in the Obituary Book of the Franciscan Abbey at Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 7, No. 1, 1911, p. 6.

[xxxii] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, p. 212.

[xxxiii] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, pp. 211-2.

[xxxiv] Knox, H.T., The de Burgo Clans of Galway, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. IV, 1905-6, no. i, p. 59.

[xxxv] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, p. 212.

[xxxvi] Sayles, G.O. (ed.), Documents on the Affairs of Ireland before the King’s Council, Dublin, I.M.C., 1979, pp. 126-7. No. 155. ‘The advice tendered to Elizabeth de Burgh by her council in Ireland 1327.’

[xxxvii] Sayles, G.O. (ed.), Documents on the Affairs of Ireland before the King’s Council, Dublin, I.M.C., 1979, pp. 126-7. No. 155. ‘The advice tendered to Elizabeth de Burgh by her council in Ireland 1327.’

[xxxviii] Knox, H.T., The History of the County of Mayo to the close of the sixteenth century, Dublin, Hodges, Figgis & Co., Ltd., 1908, p. 130.

[xxxix] Freeman, A.M. (ed.), The Annals of Connacht (A.D. 1224-1544), Dublin, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1996, (first published 1944), pp. 268-9.

[xl] Connolly, P., An Attempted Escape from Dublin Castle: The Trial of William and Walter de Bermingham, Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 29, No. 113, May 1994, pp. 100-108; Sayles, G.O., The Legal Proceedings against the First Earl of Desmond, Analecta Hibernica, No. 23, 1966, pp. 1,3, 5-47.

[xli] Orpen, G.H., Ireland under the Normans 1216-1333, Vol. iv, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1920, p. 242.

[xlii] Coleman, A., Regestum Monasterii Fratrum Praedicatorum de Athenry, Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. I, 1912, p. 212.

[xliii] Connolly, P., An Attempted Escape from Dublin Castle: The Trial of William and Walter de Bermingham, Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 29, No. 113, May 1994, pp. 100-108; Sayles, G.O., The Legal Proceedings against the First Earl of Desmond, Analecta Hibernica, No. 23, 1966, pp. 1,3, 5-47.

[xliv] Knox, H.T., The History of the County of Mayo to the close of the sixteenth century, Dublin, Hodges, Figgis & Co., Ltd., 1908, p. 132; Cal. Patent Rolls, 7 Edward III, p. 463, membrane 23; 7 Edward III, p. 486, membrane 6. ‘Matilda, late the wife of William de Burgo, Earl of Ulster, was ‘staying in England’ by early August of 1333. One John Gernoun was appointed on 1st December 1333 as guardian to the heiress Elizabeth ‘a minor dwelling in England’ with power to sue and defend all pleas for or against her in Ireland for one year.