© Donal G. Burke 2015

The oldest surviving church constructed specifically for the use of the Protestant Church in the east of County Galway is that erected in what would become the village of Eyrecourt at the expense of the Cromwellian Captain John Eyre.[i] Its founder had been the beneficiary of significant lands granted by the Cromwellian authorities in the east of the county in the mid seventeenth century, much of which had formerly been in the possession of various Maddens, Horans and other families long established in the region.

In the midst of hostile neighbours and an uncertain political climate John Eyre sought to consolidate his hold on his lands as early as possible and began construction work on the building of a large county seat for himself at the townland of Killenihy or ‘Killeno’ in the parish of Donanaughta.[ii] The mansion, called Eyrecourt Castle, was built on the grounds of a long robust two-storey early-seventeenth century house, formerly the property of a dispossessed branch of the O Maddens. The existing house was retained and incorporated into the collection of ancillary buildings to the rear of the new house. Despite the Restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660 Eyre managed to retain ownership of his estates in east Galway and by 1677 had constructed a small Protestant chapel in close proximity to a small ringfort or lios known as Killinehy or Killelehy fort and at what would be one of the entrances to his residence to serve the needs of his family and a small community of Protestant settlers whose presence he had facilitated in the area.

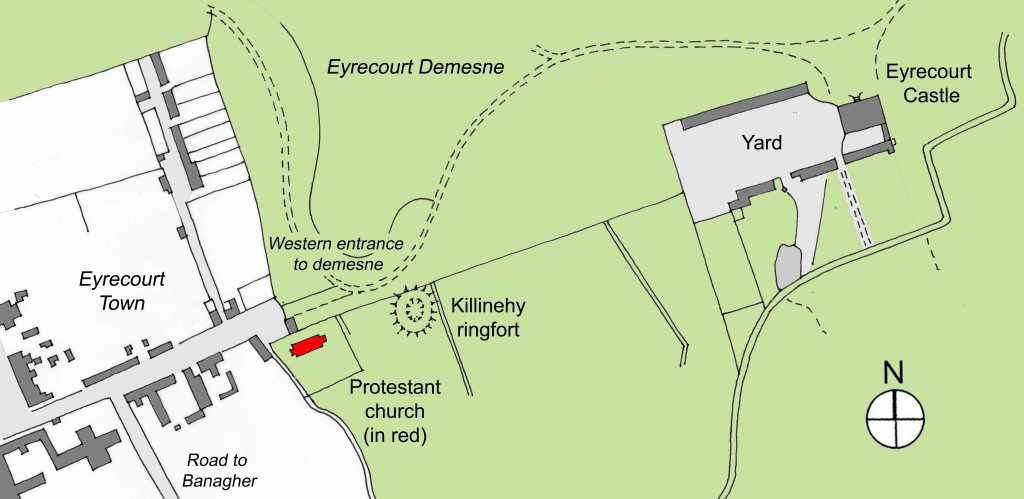

Location of the 1677 Protestant church (in red colour) at Eyrecourt in the mid-nineteenth century

While the King’s grant of manorial status relating to Eyre’s lands of two years later made reference to the existence of the church, its foundation was confirmed by a commemorative limestone tablet inserted in the south wall of the church which read; ‘JOHANES EYRE DE EYR-COURT ARMIGER PROPRYS SUMPTIBUS AD HONOREM CULTUMQUE DIVINUM HANE EDIFICAVIT ECCLESIAM, ANNO DOMINI 1677.’[iii]

The church was small in size in comparison with churches later erected in the village and consisted of a narrow nave, rectangular on plan 6m wide x 12m long, oriented on an approximate east-west axis, with a simple bell cote above its east gable and a small porch with a pointed-arched doorway and small side windows annexed thereto. A short and narrower chancel approximately 4m wide was constructed at the west end of the nave, accessed by a wide arched opening. While the chancel was lit by one large square-headed window in its gable, the nave was lit by four square-headed windows, two on the south and two on the north elevation, between the latter two of which was located a low-level square-headed internal niche. Both north windows were later blocked up, as were both porch side windows. (After its redundancy as a place of worship the entrance doorway was also partially blocked up.) The church had little or no architectural elaboration and a brick vault was constructed at one stage in the life of the building in the floor of the chancel to serve as a burial space for members of the Eyre family. About its small graveyard a stone boundary wall and entrance gate was constructed, which would appear to date from the nineteenth century, above which gate was inserted a quatrefoil stone tablet bearing the inscription ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth.’

The overgrown ruins of the 1677 church and graveyard boundary wall between the village gates to the demesne on the left and the later Park Cottage on the right

Entrance gateway to the 1677 church and graveyard

In view of Eyre’s building of this church and having ‘brought several Protestant families together’ ‘and in order to promote and encourage an English plantation there’ the King by patent dated 5th February 1679 created Eyre’s lands and others at Eyrecourt into ‘the Manor of Eyre-Court, with five hundred acres in demesne; power to create tenures; to hold court leet and baron and a law-day or court of record; to build a prison; to appoint seneschals, bailiffs, gaolers and other officers; to receive all waifs, estrays, fines, &c.; to impark five hundred acres in free warren, park and chase; to hold a market on Wednesday and two fairs more on 29th June and on Thursday after twelfth day, and the day after each at Eyre-Court.’[iv] The grant of 1679 significantly altered the landscape about Eyrecourt thereafter. His new mansion, built in an architectural style new to the country and situated as a classical object in an ordered and landscaped demesne, announced his arrival as a significant landed proprietor and the arrival of a new order in the county and country. The demesne lands he created lay principally to the north and east of his mansion, while on the edge of his demesne a small planned village developed, its main street leading to the western gates to the demesne. The demesne itself was composed of several earlier townlands and denominations whose names were later went out of use and Eyre’s church was located on the boundary of that demesne with the village but within the confines of the demesne.

A small community of minor Protestants was evident at an early stage in the life of the village who would later be buried in the small graveyard about Eyre’s church. Among the earliest buried there, with the exception of the Eyre family, were Henry Canneville, who died in 1719, at the age of 90 years and James Banco, who died, aged 74 years, in 1722. With the exception of a small number of Protestant families who settled locally in the early seventeenth century but who suffered persecution at the outbreak of the 1641 Rising, their age would point to these men as having been among the first of a minor class of Protestants who settled in and about the village in the mid to late seventeenth century. While it is possible a small cluster of houses may have existed in close proximity to the earlier house of the Maddens at Killenihy the village which developed about the western gates of the demesne appears to have been one of the first planned villages in east Galway.

Captain John Eyre, by his wife Mary, had six children, two of whom, Rowland and Katherin died young and unmarried in their father’s lifetime. At his death on 22nd April 1685 he had two sons and two daughters then surviving; John, Samuel, Mary and Anne.[v] At his death his two sons were married. John, the eldest son and heir, was married to Margery, daughter and co-heir of Sir George Preston of Craigmiller, Scotland while Samuel married as his first wife his cousin, Jane, daughter of Edward Eyre of Galway.[vi] His daughter Mary was married to George Evans of Ballygranane, County Limerick. Anne, his youngest daughter, was unmarried at the time of her father’s death.[vii] She later married one Richard St. George.[viii] Captain Eyre’s Funeral Entry in Ulster’s Office stated that he was buried ‘in the parish church of Donanaght built by himself near Eyrecourt.’

Replacement as a place of worship

Eyre’s church was eventually deemed to be too small for its congregation and was replaced as a centre of worship for the Anglican Church of Ireland community when a new church was built ‘near the centre of the town’ at the north-western corner of Market Street.[ix] The new Protestant church would appear to have been erected about the early decades of the nineteenth century. In an account of the state of the Established Church of Ireland in the diocese of Clonfert and Kilmacduagh in 1820 there was only one church then in use in the town of Eyrecourt and that church was described as ‘newly erected.’[x] (At that time Rev. Richard Eyre LLD was resident in the town and had cure of souls in the vicarages Donanaghta, Meelick, Fahy, Tyrenascragh, Killimer, Kilquane and in Kilmacunna, this last situated across the river Shannon in the parish of Lusmagh. There was no Protestant curate at that time in the parish of Donanaghta nor a glebe house, the glebe lands described as supposedly consisting of three and a half acres in the centre of Eyrecourt Demesne, ‘with boundary defaced.’)[xi] The newly constructed church was described in 1837 by Samuel Lewis in his ‘Topographical Dictionary of Ireland’ as ‘a plain building in Eyrecourt, erected by aid of a loan of £307’ from the Board of First Fruits.[xii] From this new church the road whereupon it was constructed became known as Church Lane.[xiii]

When Patrick O Keefe visited the parish of Donanaghta in 1838 he recorded that Eyre’s church of 1677 had been roofless until approximately three years earlier (c. 1835) when it was slated. The church was not used as a place of worship at that time and, despite the re-slating, it was still not used for worship.[xiv] The early nineteenth century church was exhibiting ‘signs of decay’ by about mid century and having been pronounced ‘dangerous and incapable of restoration,’ ‘it was decided to take it down and build an entirely new edifice on another site.’[xv] The early nineteenth century structure was replaced as a place of worship by a new, larger and more elaborate Gothic Revival church dedicated to St. John the Baptist, constructed across the road on Church Lane and was demolished a short time before the consecration in September of 1868 of its replacement. The newspaper correspondent who reported in 1868 on the consecration of the new building described the original seventeenth Eyre’s church as still in use ‘as a vault for the interment of members of the Eyre family.’[xvi]

Following the sale of Eyrecourt Castle and demesne in the early twentieth century and the departure of the Eyres in the 1920s, the ruins of the 1677 church and the graveyard whereupon it stood became a part of the property of the family who acquired the castle. Over succeeding decades Eyrecourt Castle fell into a ruinous state and the condition of the small church at the entrance gate between the demesne and the village grew progressively worse and its graveyard overgrown with saplings, bushes and nettles.

Eyrecourt church bellcote behind overgrowth in the early twenty-first century

In the late twentieth century the church and graveyard were in an advanced state of decay and a number of disturbed coffins were visible beneath the damaged chancel burial vault.[xvii] Ida Gantz, writing in 1975 in her ‘Signpost to Eyrecourt’ noted that in the will of Captain John Eyre who died in 1685 he commended his soul to God ‘and his mortal body to be buried in the little church by Duffy’s cottage which is now no longer accessible.’[xviii]

The cottage to which Gantz referred was a gate lodge, the rendered and white-washed curvilinear west elevation of which was located between the former demesne gates and the graveyard wall and formed part of the demesne boundary wall. It was occupied in the mid to late twentieth century by a Duffy family and served as one of two gatehouses giving access to the demesne, the other located at the eastern entrance.[xix]

The classically-designed stone piers whereupon were hung the gates at the eastern entrance to the demesne were sold in the late twentieth century by the landowner but were subsequently bought from the purchaser by the local community through the Eyrecourt Community Group who, after negotiations with the landowner, had them re-erected at the eastern, village entrance to the demesne. In accommodating the eastern gates at the village entrance Duffy’s cottage was demolished.

Certain works were undertaken as part of a State-sponsored employment scheme in the 1980s, comprising for the most part the cleaning of the graveyard and the straightening up of a number of headstones. Works on that occasion did not touch on the fabric of the church proper.

In 1994 Dr. Christopher Cunniffe, later Galway Community Archaeologist, undertook a detailed survey of the graveyard and recorded the details of the thirty-two inscribed funereal monuments or stones in the graveyard, a record of which headstones and memorials are provided, by kind permission of Dr. Cunniffe, in the associated article under ‘Graveyard burials.’

The 1677 Eyre church and its graveyard are in private ownership and are inaccessible to the public.

A detailed record of these burials with an associated layout map of graves, prepared by Dr. Cunniffe, are also available at the following link; http://www.irelandxo.com/node/389

For further details regarding the Eyre family, refer to ‘Eyre of Eyrecourt’ under ‘Families’ and ‘Heraldry.’