Ivy now surrounds the remains of the tomb of Nicholas Hannon and his wife Rayneta Madden, that thick mature ivy that grows between the crevices and joints of ancient stonework and over time destroys its host.

It is a sad sight now to see this tomb in such an advanced state of neglect. When built in 1637, during the reign of King Charles I, it was the epitome of fashionable local funerary architecture, a fitting monument to the leading family of the name Hannon, major landholders of Gaelic origin in the region about the parish of Abbeygormacan in east Galway.

Hidden away from public view, the tomb languishes out of sight in the ruins of a small side chapel, the only stone walls remaining fully intact of the medieval Augustinian monastery of St. Mary or Via Nova at Abbeygormacan.

The peace and tranquility one experiences here renders the ruins of Abbeygormacan an appropriate resting place for a man who not only lived through the turbulent and uncertain early decades of the seventeenth century but played a prominent role in the affairs of his county as one of twelve Galway men, now largely forgotten, whose resolution prevented for a time the confiscation of much of County Galway and its plantation with English or Scottish settlers.

Nicholas Hannon and the Plantation of Connacht

Sir Thomas Wentworth, later Earl of Stafford, the King’s powerful and devoted favourite, arrived in Ireland in 1633 as Lord Deputy. The plantation of Ulster in the north of Ireland, involving the confiscation of lands and their reallocation to new settlers regarded as potentially more loyal to the Crown, had already begun.

Wentworth’s plans as Lord Deputy caused panic among the landholders of County Galway, whose legal title to their lands was in danger of being called into question. The Lord Deputy’s scheme involved establishing a jury in each county in Connacht and bullying them into admitting that the legal title to their lands was properly the King’s as the rightful heir in line of descent from William, the last de Burgh Earl of Ulster and Lord of Connacht, who had been murdered in 1333. If he could succeed in having all the county juries admit the King’s title he could thereafter, in the King’s name, begin confiscations and allocate large tracts of lands to new settlers. The juries in each county were composed of some of the most prominent landholders of that county and one by one, the juries in Roscommon, Sligo and Mayo caved in to Wentworth’s intimidation and deceptions.

Sir Thomas Wentworth (c. 1633) after Sir Anthony Van Dyck. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Wentworth met with continued success until he came up against the Galway landholders. There he was vigorously opposed by the most influential peer in the county; Richard Burke, 4th Earl of Clanricarde, who worked ceaselessly through his connections at Court and his influence among the landed proprietors of Galway. Nicholas Hannon was chosen as one of the twelve jurors empanelled for County Galway. (Given the high social standing of the majority of the jurors, it would appear likely that this was that same Nicholas who had the tomb erected at Abbeygormacan in 1637.)

While Clanricarde was in England, Wentworth established himself, his officials and troops at Clanricarde’s new castle at Portumna in 1635, reputedly treating the place with little respect. There, he had the jury meet and used every means at his disposal to pressurise them into finding in favour of the King. The Galway jurors, to Wentworth’s seething anger, remained steadfast and refused to find for the king.

Wentworth had Nicholas Hannon and all the jurors handed over to the Court of Castle Chamber, thrown into prison, their estates confiscated and each fined the then colossal sum of £4,000. The jurors later petitioned to be released but, when informed that they would only be released upon the condition that they admit that they had made an error and committed perjury, they rejected the condition. Their steadfastness and sacrifice proved a significant setback for Wentworth, whose plans to plant Connacht were thereby temporarily stalled.

The delay caused by the juror’s decision proved decisive. In 1637 Wentworth had another jury convened at the Franciscan Abbey outside the town of Galway to deal with the matter again and, intimidated by the ill treatment of the previous jury, they found in favour of the Crown’s title to the county. Wentworth proceeded to survey the entire province as a preliminary to plantation but political distractions on the Continent and in Scotland delayed and thereby prevented the actual implementation of the proposed plantation prior to Wentworth’s fall from power.

For many of the actors involved the cost was high. Ulick, 1st Marquis and 5th Earl of Clanricarde blamed Wentworth’s plans and harrying of his father Richard for hastening his death in 1635. Martin Darcy, the Sheriff of Galway who chose the Portumna jurors, died in prison in 1636, while Wentworth himself would later be recalled to England in 1639 where he continued to serve his king until he fell foul of his enemies in Ireland and England, was declared guilty of high treason and beheaded, to the great dismay of the king, who reluctantly signed his death warrant. King Charles I would himself be beheaded eight years later.

With regard to Nicholas Hannon and the other Portumna jurors, despite Wentworth’s execution, their eventual release and the reduction of the crippling fines achieved through the influence of the Earl of Clanricarde, the jurors or their heirs were still required to pay their fine until King Charles later remitted the outstanding amounts. An attempt was later made, under the reign of his son, King Charles II, to have the juror’s heirs pay the remaining amount but in 1662 the king finally decreed that the remaining sums should remain remitted.

Those lands that the principal members of the Hannon family held about Abbeygormacan later passed from their hands. The O Hannons were long associated with Abbeygormacan, with individuals of that name serving the Church in the diocese of Clonfert and as Religious at the abbey over succeeding centuries. Nicholas Hannon held the castle of ‘Castleheyny’ about Abbeygormacan in the early decades of the seventeenth century but there now remains little physical reminder of the Hannon presence thereabout with the exception of this tomb.

The Hannon tomb today

A fine late example of high-status altar tombs constructed across Ireland from the medieval period in abbey churches, the tomb at Abbeygormacan is of sufficient architectural and historical worth to merit an intervention to ensure its preservation. As a protected structure any unauthorised works to save the tomb are prohibited but it would reflect poorly upon the country and county should the State, through its Local Authority or another authorised body, fail to act before ivy and neglect bring about the collapse of this fine memorial.

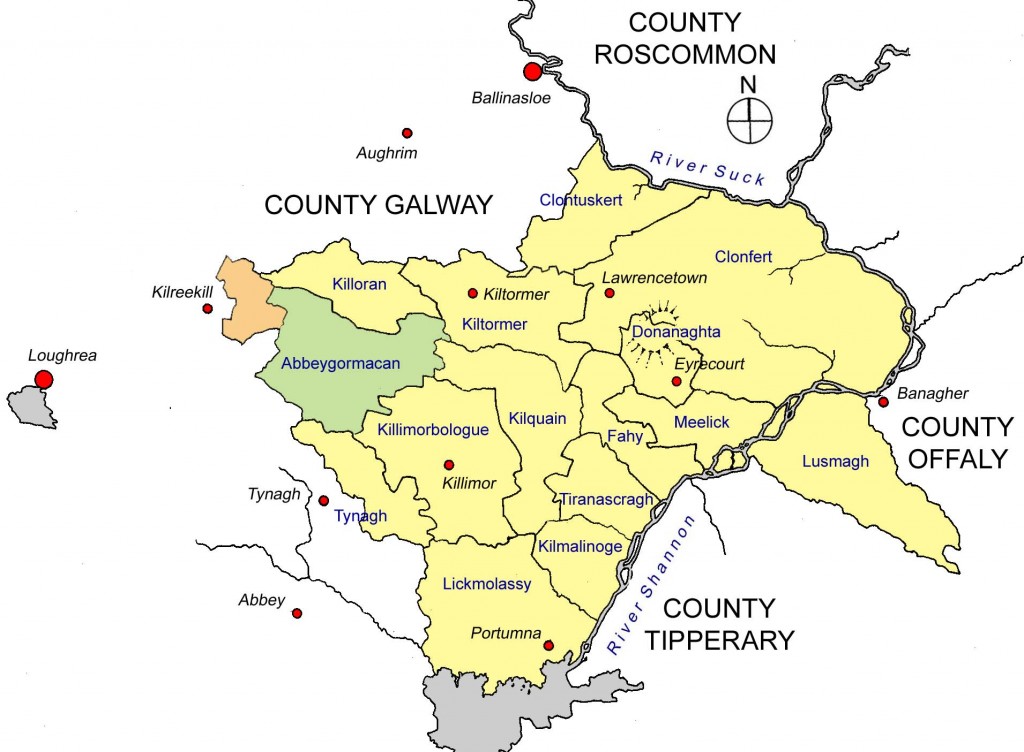

Map showing the location of that part of the parish of Abbeygormacan (in green) that lies within the mid nineteenth century barony of Longford (in yellow) in the east of County Galway. Modern towns and villages shown in red.

The tomb lies within the ivy-covered side chapel or transept, to the right of this photograph, the substantial wall in the foreground the remains of the southern wall of the nave and chancel of the monastery church, dotted now with numerous modern graves.

The late medieval gated doorway leading into the roofless ruins of the side chapel, with the Hannon tomb, set into the gable wall, in the background.

A dislodged stone from the ‘altar slab’ that once formed part of the coverlid of the tomb now lies on the ground among the rubble and debris before the tomb. Inscribed with the words ‘Orimuret mori mur hoc monumentum erigi fecerunt D: Nicholaus Hanyn et Ranyneta Maddyn ipsius uxor pro se: suis que prosteris Anno Domini Jan 1637,’ the tomb was apparently designed as the resting place of the most prominent member of the family. This Nicholas would appear therefore to be Nicholas of Castleheyny, gentleman, whose lands lay across the parishes of Abbeygormacan, Kiltormer, Killimor and Tynagh in the barony of Longford in east Galway in the early to mid decades of that century.

The classically-detailed keystone, above the tomb’s arch, dropped from its original position, displaced by the encroaching vegetation.

The Hannon tomb bears certain architectural similarities to the even later tomb of Thomas Burke, the senior-most representative of the Burkes of Pallas, a significant landholder in south-east Galway, erected in 1649 in a side chapel at Kilnalahan Abbey, in the village of Abbey, in the south-east of the county. The Burke tomb, however, is in a much better state of preservation, having the advantage of being located beneath an intact roof.

The better preserved near contemporary tomb erected at Kilnalahan Abbey by Thomas Burke of Pallas, commemorating his parents, wives and posterity about twelve years after the construction of the Hannon tomb.

Michael Glynn from Abbeygormacan with his dog ‘Rex’ in front of the side chapel doorway. Michael was cycling by as I arrived at the ruins of Abbeygormacan. On his journey back home later he stopped for a chat and we both left the abbey at the same time, closing its gate behind us.

For further details on the Hannon family, refer to ‘Hannon’ under ‘Families’ in the main body of the website.

Comments are closed.