© Donal G. Burke 2013

The Trench family who established themselves in east Galway in the seventeenth century were of Huguenot (French Protestant) origin, having previously sought refuge in England from persecution in their homeland about the late sixteenth century.

Frederic de la Tranche

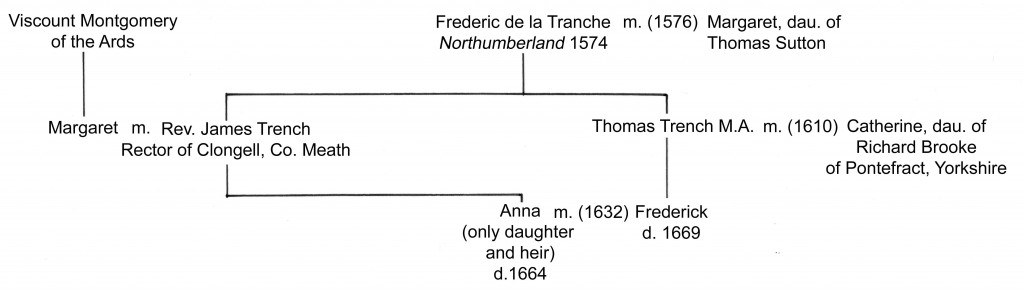

The family claim descent from one Frederic de La Tranche, whose name was said to derive from the family’s origins in the town of La Tranche in Poitou.[i] This Frederick was reputed to have fled France as a result of religious persecution and settled in Northumberland in 1574. Two years after his arrival in England he married Margaret, daughter of Thomas Sutton and had a number of children, including at least two sons, James and a younger son whose name was given variously as Thomas or Adam Thomas.[ii] Conflicting pedigrees relating to the family at this time give three sons of Frederic de la Tranche; Thomas, his eldest son and heir, James and Adam-Thomas.[iii]

Rev. James Trench, Rector of Clongell, County Meath

James appears to have been the first of the family to establish himself in Ireland. He pursued a career as a Protestant clergyman and appears in that role in the Protestant church in Ireland at a time when that church began to concentrate on appointing English or Scottish-educated clergy to Irish posts, given the previous poor interest shown by native clergy.

He was living in Ireland in 1605 and was presented to the rectory of Clongell or Clongall in County Meath.[iv] His marriage to Margaret, daughter of Viscount Montgomery of the Ards would suggest that his family were either considered of sufficient gentility at this time for this to be considered a suitable match for the peer’s daughter or of sufficient financial resources to render it satisfactory. (The family claimed that the Frederic who fled France in the late sixteenth century had been a nobleman and Seigneur de La Tranche.)[v]

Frederick Trench

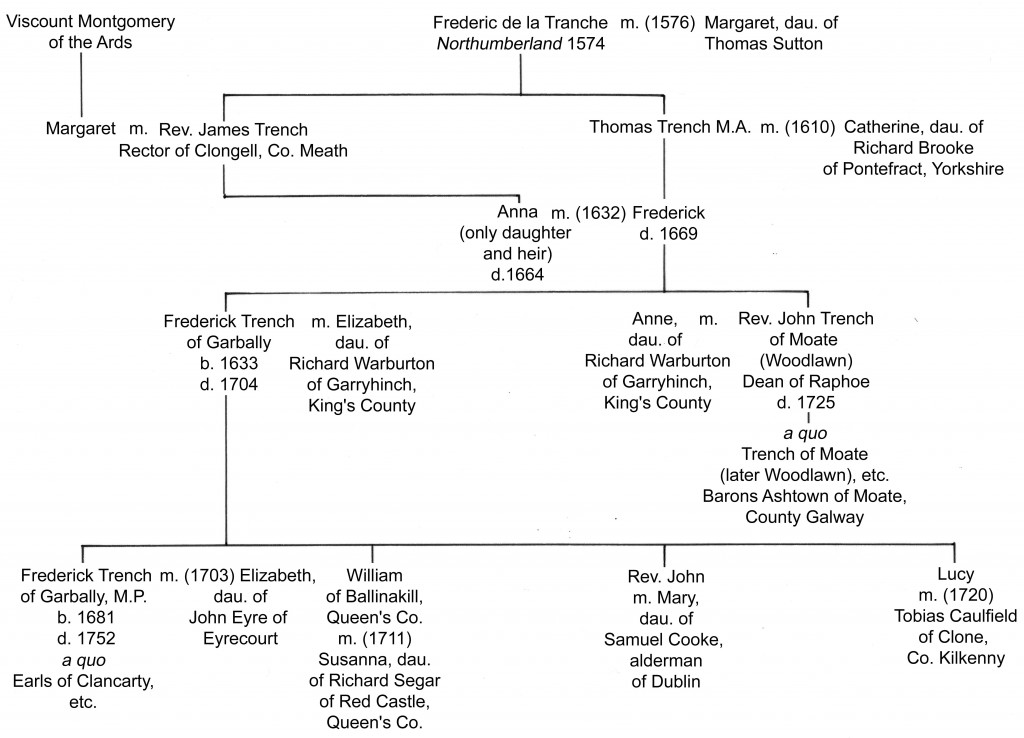

James’ immediate family appear to have seen sufficient opportunity for advancement in Ireland for his nephew Frederick Trench to settle in Ireland in 1631.[vi] This newly arrived Frederick was son of James’ brother Thomas or Adam-Thomas and married James’ only daughter Anna, his cousin, thus consolidating their financial interests. The couple had at least two sons; Frederick, born in 1633 and John.[vii]

Another account of the early generations of the family in Ireland, at variance with the majority of accounts, gave Thomas Trench, son of Adam-Thomas la Tranche as that Trench who married his cousin Anne, daughter of Rev. James Trench and had two sons Frederick and John.[viii] (This account gave Rev. James as the second son of Frederick de la Tranche and Adam-Thomas as the youngest son.)[ix]

Pedigree of the earliest of the Trench family to settle in Ireland, a number of variations of which occur in sources.

Both Frederick (who settled in Ireland in 1631) and his father-in-law appear to have extended loans to various individuals with the latter’s lands as security and thereby acquired property in County Cavan.[x] It appears to have been this Frederick who initially acquired lands in east Galway in the mid seventeenth century that would eventually form the core of his descendants estates in later centuries. He does not appear as a significant landed proprietor in east Galway in the late 1630s but within thirty years appears to have acquired an interest in lands in the parish of Kilcloony in east Galway.

The Trench family were among a substantial number of families bearing surnames alien to the Irish landscape who settled in the country in the aftermath of the Nine Years War. Some of those families were recipients of lands of individuals whose property had been confiscated by the Crown for their part in rebellion, while others arrived as clergymen of the new Protestant religion. While not all shared a similar background, they were for the most part Protestants. They settled in a country where the native population was still for the most part Roman Catholic and who were regarded by the government as a potential threat to the security of Protestant England. The Roman Catholic Church was actively fighting to counter the Protestant Reformation and the possibility of a Spanish invasion of Ireland was of grave concern to an increasingly anti-Catholic English government. As such many of the new settlers such as the Trenches were deeply unpopular among a large proportion of the native population, who were for the most part Roman Catholic and who feared further confiscations and colonisation.

The 1641 Insurrection and the Cromwellian Period

Taking advantage of divisions between the King and the English Parliament, a large proportion of the disenchanted Irish population rose in rebellion in 1641, in which many of the new settlers suffered depredation or lost their lives. Many of the leading Roman Catholic landholders took part in the uprising and met with considerable initial success. In 1649, after the forces of the English Parliament had successfully dealt with the forces loyal to the King in England, a Parliamentary army under Oliver Cromwell was sent from England to suppress Ireland. By 1652 the Cromwellians had effectively defeated the various Irish armies and proceeded to redistribute the land ownership in Ireland in part to pay those who had financed and fought their campaigns and in part to install a new landowning class in Ireland favourable to their government.

To accommodate those being allocated lands, property in whole or in part was confiscated from existing landholders and those were ordered to transplant into Connacht. Those who held lands in Connacht were to have their lands confiscated in whole or in part to provide land for their transplanted countrymen or to provide for Cromwellian grantees such as Oliver Cromwell’s son Henry Cromwell, Captain John Eyre and others.

The Tully estate in the parish of Kilcloony

About the time of the Cromwellian land redistributions in the late 1650s Frederick Trench appears to have acquired an interest through mortgage on lands held by the Tully family in the parish of Kilcloony near Ballinasloe Castle in County Galway. Matthew Tully, son of the deceased Kyvas, Protestant Dean of Clonfert, had lost part of his family estate during the Cromwellian confiscations but retained other lands in that parish. Those lands lay in the denominations of Kilcloony, Derrymullen, Lisacapell, Clunsayle and Caltreleagh.[xi] Part of the former Tully lands at Garbally, wherein lay their residence, was granted by the Cromwellians to one Marcus Laffan and Laurence Hammon.[xii]

Restoration of the Monarchy

Following the turmoil of that period and the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II in 1660, an Act of Settlement was passed in Parliament, in an attempt to address the complaints of those whose lands had been taken or divided by the Cromwellians and to placate those who had acquired lands at that time. Under the Act of Settlement the Tully’s former lands at Garbally were confirmed upon Colonel Carey Dillon, while others were confirmed in possession of other parts of their former estate.

The Trench family history claims that Frederick Trench settled about the parish of Kilcloony upon his acquisition of lands there and he is commonly described in pedigrees as ‘of Garbally.’[xiii] It is uncertain, however, if it this Frederick or his son of the same name who was first to settle at Garbally.

In 1669 Frederick Trench died and was succeeded by his son Frederick.[xiv]

Frederick son of Frederick Trench 1669 to 1704

Both Frederick and his younger brother John married two daughters of Richard Warburton of Garryhinch, King’s County. Frederick married Elizabeth Warburton by whom he had three sons and a daughter; Frederick, William, John and Lucy.[xv] His brother John pursued a career in the Protestant Church and would later acquire lands about Moate (later Woodlawn) in east Galway. He married Anne Warburton, by whom he would have at least one son, Frederick.[xvi]

The Tully estate under the Act of Settlement

Under the Act of Settlement Frederick Trench was confirmed in the 1670s in possession of the greater part of the lands previously left to Tully by the Cromwellians. He was confirmed in possession of lands in Lisacapall, Kilcloony and Derrymullen that appear to have previously been Tullys and the vast majority of their lands in the townland of Caltreleagh (the modern townlands of Deerpark and Eskerroe). It would appear that Trench or his father purchased part of these lands from Tully after the Cromwellian allocation of lands and extended loans to Tully with much of his lands as security.[xvii] He thereby acquired an interest in most of the remainder of Tully’s lands by mortgage. Tully, however, seated at Cleaghmore, adjacent to Garbally would remain in possession of a small acreage in Kilcloony and the entire denomination of Derrymullen despite Trench’s grant under the Act of Settlement.[xviii]

Trench was also confirmed in possession of other lands in Grange in the same parish of Kilcloony, previously granted to either an O Kelly or Egans and acquired lands nearby at Loughbowen by mortgage. In addition to these lands, the historian Fr. P. K. Egan suggested that Trench purchased Tully’s former residence and lands at Garbally from Colonel Dillon, where the family would be seated into the twentieth century.[xix]

King William and Queen Mary

Alarmed by the increasing Catholic influence and at the birth of an heir to the Roman Catholic King James II, the still powerful Protestant interest in England deposed King James, and offered the crown to his Dutch son-in-law, the Protestant Prince William of Orange and his wife Mary. The English Parliament declared James’ throne vacated in December 1688 and his daughter and son-in-law were jointly crowned King William III and Queen Mary II. The Irish Catholics rose up in support of King James, and an army was sent by the French King to reinforce James’ Irish supporters, the Jacobites.

In March 1689 James landed in Ireland to head his army here, hoping to regain his throne through Ireland and a Catholic-dominated Parliament was set up in Dublin. The Irish Catholics hoped to recover much of their former lands that they were denied under the settlements after Charles II had been restored and the Irish Parliament declared many of the Williamites, supporters of William of Orange, outlaws and their lands were to be confiscated as such. King William arrived early in the following year with his Dutch and English army, and so began the war of the two kings.

The leading Roman Catholic families responded enthusiastically to the cause of James II and six regiments were raised for the king in 1688, four of which remained active throughout the war.[xx] The officer’s ranks in the Galway regiments were swelled with members of the most prominent Catholic county families.

For their part both Frederick Trench and his brother John supported the cause of William and Mary. Rev. John Trench in particular was noted for his active support, to the extent that he would later be appointed Dean of Raphoe for his services.

The Jacobite-Williamite War

The war progressed badly for the Jacobites. After defeating the enemy at the Boyne in 1690, the Williamite army pushed south, and the Jacobites fell back towards the Shannon, to defend the river passes and hold Connacht, thereby keeping naval contact with France open through Galway and Limerick. Fortifications in east Galway such as those at Meelick and across the bridge at Banagher along with the river fortifications such as Athlone and Limerick, became the front defensive line of the Jacobite held territory. Eyrecourt likewise appears to have played host to a Jacobite garrison. The main Jacobite army was besieged at Limerick but the Williamites were forced to raise the siege, thus prolonging the war and the Jacobite army faced a long winter confined to the area behind the River line.

Rev. John Trench and the battle of Aughrim

Athlone on the Shannon fell before the Williamite army after heavy fighting, and the Jacobite army under the French general, the Marquis of St. Ruth, regrouped, first at Ballinasloe, and later, on better defensive ground, at nearby Aughrim where, on Sunday 12th July 1691, both armies clashed.

Battle raged throughout the day, with the advantage initially gained by the Jacobites. With the Williamites reasonably unfamiliar with the terrain, several local people acted as guides, including two Trench brothers, Frederick and the Reverend John Trench. The former was reputed to have provided his residence as a hospital for Williamite soldiers and a map of the Jacobite positions was reputedly given to the Williamite commander by the Trenches. One account related that in the heat of the battle, as John Trench was showing a party of troops a pass near the Jacobite-held castle, he realised that the Williamite artillery men nearby were firing their cannons too high. Inquiring of them why they did not remedy this, they replied that they had used all of their wedges under the guns and still could not depress their guns any lower, whereupon Trench grabbed his boot, cut off the heel and crammed it under the breech of the cannon, and told them to try it again. At that moment, St. Ruth appeared on horseback in the distance, and the following shot beheaded the Jacobite commander. Not having revealed his battle plan to his officers beforehand and the battle already turning against them, the Jacobites, leaderless, were thrown into confusion, and suffered a terrible defeat.[xxi]

After Aughrim, detachments of Williamites took the Shannon positions in east Galway. With the destruction of the army, the Earl of Clanricarde surrendered the town of Galway and after another siege, the remnants of the Jacobite army, under Brigadier Patrick Sarsfield, on agreeing a treaty with the Williamite commander, surrendered at Limerick and the war was over.[xxii]

For his services to the Williamite cause, the Reverend John Trench would later be made Dean of Raphoe, and a common toast, it was claimed, among Orangemen, in the following years, would be “gentlemen, the heel of the Dean of Raphoe’s boot.”[xxiii]

The war concluded with the defeat of the Jacobite army and the signing in October 1691 of the Treaty of Limerick.

The Court of Claims

Many prominent Irish Jacobite faced the prospect of losing their lands under the new government of King William and Queen Mary. The estates of those deemed outlaws and traitors in February 1688 were to be vested in thirteen Trustees and the same estates to be sold.[xxiv] A large number, however, were eligible to benefit from the ‘articles of Limerick and Galway’ that formed part of the Treaty. The terms of the treaty allowed the Jacobite soldiers and people holding out at Limerick and at Galway to either sail for France or remain in Ireland and submit to the new King. Those who submitted to the new Protestant King and Queen and were eligible to benefit from the articles were to be allowed to keep their estates intact and, if outlawed, pardoned. The hearing of cases of those seeking to avail of the articles was a prolonged affair, extending into 1699.[xxv]

Any person with a claim to lands vested in the Trustees were to present their case before the Trustees before 10th August 1700, (and later extended to 25th March 1702.) The remainder of the forfeited estates not restored by the extended deadline were to be sold before 25th March 1702 (extended to 24th June 1703.)[xxvi] The confiscated estates were to be sold only to Protestants, to secure the future of a Protestant dominated island, and the money raised from which sale to be used to pay those who had fought for King William and those who had supplied the army in Ireland.[xxvii]

In Galway few were finally declared outlaws and several notable Catholic county families managed to retain part of their estates under the articles, and so was maintained in Connacht, unlike the other three provinces, a vestige of Roman Catholic gentry, who remained locally influential, side by side with the large Protestant landowners.

There were only fourteen purchasers of these confiscated Jacobite Galway estates, and included among these was the Trenches and John Eyre of Eyrecourt.

Acquisition of forfeited Jacobite lands

Matthew Tully was among the many who had supported the cause of King James II and the lands that the family had retained after the Cromwellian period, 10 acres in Kilcloony and 188 in ‘Direnwillon’ (the modern townland of Derrymullen, about the town of Ballinasloe) were declared forfeit by the Williamite authorities. He was given as Matthew Tully of Clymore (ie. Cleaghmore), gentleman, when listed among those Jacobites indicted and outlawed for high treason against the crown of King William and Queen Mary, which would suggest that his then residence was located in the townland of Cleaghmore, adjacent to Garbally.[xxviii] With his estates pursued by Frederick Trench, Matthew Tully was among the relatively few Jacobites outlawed after the war.

Frederick Trench and Richard Warburton jointly claimed two 100l. mortgages on the lands of Cleaghmore, ‘Tullagh’ and Kilcloony that formed part of Matthew Tully’s estate. The first mortgage originated in a lease of 1682 from Matthew Tully to one Francis Dean that was later assigned to Peter Martin in trust for the same Frederick Trench. The second mortgage related to a lease of 1685 directly from Tully to Peter Martin, again in trust for the same Trench. [xxix]

Agnes, Matthew Tully’s widow, on her own her children’s behalf presented her case before the Court for Forfeited Estates prior to 1700, claiming the property her late husband formerly held at Derrymullen and Caltreleagh and elsewhere by a deed of 1671 and a mortgage dated 1684 on a half quarter of the lands of Derrymullen and elsewhere.[xxx] She appears to have been unsuccessful in her claim, with the lands being declared forfeit and finally purchased by Trench before 1703.[xxxi]

Frederick Trench in his own right claimed an estate at Clonshee, County Galway, arising out of a previous mortgage, formerly the lands of one outlawed Hugh Kelly.[xxxii] He also claimed an estate of one hundred and thirty-three acres in the townland of Clonecaltrie in County Roscommon, formerly the property of Hugh Kelly, who may have been the same individual. [xxxiii]

By the end of the seventeenth century Frederick Trench had built a sizeable estate about the former Tully property in Kilcloony and, with the decline of the latter, the O Kellys of Creagh and the Elizabethan Brabazons at Ballinasloe in the turmoil of the latter half of the century, the Trench family established themselves as the foremost landholders in the immediate area. About their newly consolidated estate the modern town of Ballinasloe would develop.

His brother John, Dean of Raphoe, about 1702 also purchased lands that had been deemed forfeited by one Peter Martin about Moate (ie. Woodlawn) in east Galway, not distant from his brother’s estate about Ballinasloe.

Of the two Trench brothers, Frederick died in 1704 and was succeeded at Garbally by his eldest surviving son Frederick Richard. John, Dean of Raphoe, died in 1725 and was succeeded at Moate by his son Frederick.[xxxiv] From this latter Frederick would descend the later Trenches of Woodlawn and Barons Ashtown of Moate, County Galway in the Peerage of Ireland.

Of the younger children of that Frederick of Garbally who died in 1704, William would marry in 1711 Susanna, only daughter and heir of Richard Segar of Redcastle in Queen’s County, by whom he had a family. In certain pedigrees he is given as settled at Ballinakill in Queen’s County but in articles of agreement between his brother Frederick and sister Lucy in 1715 he is described as ‘of Redcastle, Queen’s County.’[xxxv] John, the third son, pursued a career in the Church and married Mary, daughter of Samuel Cooke, alderman of Dublin, by whom he had two daughters, while their sister Lucy married in 1720 Tobias Caulfield of Clone, County Kilkenny, by whom she had three daughters.[xxxvi]

Frederick Richard Trench of Garbally 1704 to 1752

Frederick Richard, son of Frederick Trench of Garbally built on the work of his predecessors. In 1716 he purchased the nearby estate of the Spensers who had been transplanted by the Cromwellians in the previous century and been allocated lands about the parish of Creagh and Kilcloony that had formerly been the property of Brabazons and others. The title to these lands was disputed between the Brabazons and Spensers but the latter appear to have been in possession or held greater claim as it was their property that Trench purchased.[xxxvii]

He married Elizabeth, daughter of John Eyre of Eyrecourt in 1703, by whom he had four sons and six daughters; Richard, Eyre, Frederick (who died in infancy), William, Elizabeth, Jane, Rose, Emily, Mary and Mabel.[xxxviii] He served as Colonel of a regiment of dragoons in County Galway, as High Sheriff of the County and Member of Parliament.[xxxix]

He died in 1752 and was succeeded at Garbally by his son Richard.

Of his younger children; Eyre Trench, the second surviving son was seated at Ashford in County Roscommon. He married about 1770 Charlotte, daughter of Kean Trench of Arnaghmore, County Sligo and of Dublin, by whom he had an only child, Frederick Eyre Trench of Kellistown, County Carlow from whom descended the Trench family of Clonfert House, parish of Clonfert, County Galway.[xl]

William, the third surviving son of Frederick of Garbally and Elizabeth Eyre married Anne Colpoys of Tipperary and served as an archdeacon in the Protestant Church of Ireland.

Of Frederick’s four daughters, Elizabeth married Rt. Rev. Nicholas Synge, D.D., Protestant Bishop of Killaloe and Kilfenora, Emily married Richard Eyre, M.P. and High Sheriff of County Galway, Mary married Thomas Shaw of Newford, County Galway and Mabel married Frederick Netterville of Finglas in Dublin.[xli]

Richard Trench of Garbally 1752 to 1768

In March of 1732 Richard Trench married Frances, only daughter and heir of David Power of Coorheen, near Loughrea, High Sheriff of County Galway, a man who had been zealous in the persecution of Roman Catholic clergy within his jurisdiction.

The Powers had been transplanted by the Cromwellians and descended from the Anglo-Norman Barons Power or de la Poer. Through marriage they were descended from MacCarthy Viscounts Muskerry and Earls of Clancarty, a connection that would prove significant on the acquisition of a title by the as yet untitled senior line of the Trench family.

The marriage brought considerable wealth and property to the Trench family. As heiress of her father’s estates, the Trench family inherited through Frances Power her father’s estates in the baronies of Loughrea, Dunkellin and Leitrim in County Galway. Frances was also heiress of her mother’s Keating estates in counties Kilkenny, Carlow and Dublin and these also accrued to the Trench family through this marriage.[xlii]

As a result of this marriage he and his children came to assume the additional surname of Power. By his wife Richard Trench had six sons and five daughters; Frederick Power Trench and David Power Trench, who both died in infancy, William Power Keating Trench, John Power Trench, Eyre Power Trench and Nicholas Power Trench, Elizabeth Power Trench, Hester Power Trench, Rose Power Trench, Jane Power Trench and Anne Power Trench.[xliii]

Ballinasloe would appear to have been only a small settlement into the seventeenth century but developed into a town from the eighteenth century under the Trench family. One traveller, Thomas Molyneaux, described it in 1709 as ‘a very pretty scituated village on ye river Suck.’ Frederick Trench had received a charter from King George I to hold a livestock fair in October at Ballinasloe in 1722 and in 1757 his son Richard received a patent to hold an annual fair at Dunlo in Ballinasloe on the 17th May and 13th July. Both of these two later fairs, in addition to the October fair, became important commercial affairs in the life of the surrounding community. Early in the following century the October fair, held on the park at Garbally, was regarded as ‘one of the largest of its kind in Europe’ and the ‘chief fair for fat cattle’ in County Galway, ‘to which the buyers from Cork, Limerick and all parts of Leinster and frequently from England and Scotland repair.’[xliv] While a claim was made in a memoir relating to the Trench family that the Ballinasloe fair originated in the eighteenth century Royal Letters Patent, it was believed by many in the nineteenth century that the fair had developed at a much earlier period, without a patent, to provide cattle and beef for export from the port of Galway.

Along with a number of other landed proprietors in County Galway in the mid eighteenth century the Trenchs also sought to foster the development of a linen or woollen industry in the town, the July fair noted in particular as the wool fair.

Although the presence of these fairs and improving landlords had a beneficial influence on trade in the town, Ballinasloe was still regarded in the early decades of the nineteenth century as ‘a small place, though one of the most prosperous towns in the county’ and it would appear to have been in the following century that the town developed most significantly.[xlv]

During his father’s lifetime Richard Trench served as Member of Parliament in Ireland for the borough of Banagher in King’s County from 1734 and continued to do so until 1761. From 1761 until 1768 he served as Member of Parliament for County Galway. He died in 1768.

Continued under ‘Trench Earls of Clancarty.’

[i] Brydges, Sir E., A biographical Peerage of the Empire of Great Britain, Vol. IV, London, J. Nichols & Co., 1817, p. 435.

[ii] Brydges, Sir E., A biographical Peerage of the Empire of Great Britain, Vol. IV, London, J. Nichols & Co., 1817, pp. 175-6; Agnew, Rev. David, C.A., Protestant Exiles from France in the reign of Louis XIV, private circulation, pp. 362-3.

[iii] Debrett, J., Debrett’s Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 2, (17th edition), London, G. Woodfall, 1828, pp. 726-8; Agnew, Rev. David, C.A., Protestant Exiles from France in the reign of Louis XIV, private circulation, pp. 362-3.

[iv] Agnew, Rev. David, C.A., Protestant Exiles from France in the reign of Louis XIV, private circulation, pp. 362-3; Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 95.

[v] Agnew, Rev. David, C.A., Protestant Exiles from France in the reign of Louis XIV, private circulation, pp. 362-3.

[vi] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 95.

[vii] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2.

[viii] Agnew, Rev. David, C.A., Protestant Exiles from France in the reign of Louis XIV, private circulation, pp. 362-3.

[ix] Agnew, Rev. David, C.A., Protestant Exiles from France in the reign of Louis XIV, private circulation, pp. 362-3.

[x] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 95.

[xi] Fr. Egan equates Clunsaile with the modern denominations of Gorteen, Derradda, Knockglass and Ballynamokagh in the parish of Kilclooney, while Caltreleagh is those of Deerpark and Eskerroe. (Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 315, Appendix V.

[xii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 309-310.

[xiii] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2.

[xiv] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 133.

[xv] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 150-2.

[xvi] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2.

[xvii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 95, 109.

[xviii] Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, Dublin, 1960, p. 72. Cleaghmore would later form part of the town of Ballinasloe as it expanded over later years.

[xix] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 107.

[xx] Mulloy, S., Galway in the Jacobite War, J.G.A.H.S., Vol. 40, 1985-6, pp. 3-4.

[xxi] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 102-9.

[xxii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 102-9.

[xxiii] Egan, Rev. P.K., The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 102-9.

[xxiv] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. xix.

[xxv] Simms, J.G., Irish Jacobites, Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, 1960, pp. 14-5.

[xxvi] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. xix.

[xxvii] MacGiolla Choille, B. (ed.), Books of Survey and Distribution, Vol. III, County of Galway, Dublin, Stationary Office for the I.M.C., 1962, p. xix.

[xxviii] Analecta Hibernica No. 22, IMC, Dublin, 1960, p. 72. Cleaghmore would later form part of the town of Ballinasloe as it expanded over later years.

[xxix] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 318. Entry nos. 2755-6. The Warburtons were connected by marriage to the Trenchs. One account gives Frederick’s brother John married to Anne Warburton, while another, repeated by Joeph Foster in his ‘Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage’ of 1822 gives John’s wife as Mary, daughter of Samuel Cooke, alderman of Dublin, by whom he had two daughters; Eliza and Mary. While Mary was said to have been married in 1738 William Peisley-Vaughan of Golden Grove, Kings County, Eliza was said to have been married William Warburton of Donecarney, Queen’s County. (Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 150-2.)

[xxx] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 345. Entry no. 3005.

[xxxi] P.K. Egan, The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 109.

[xxxii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 318. Entry nos. 2755-6.

[xxxiii] Trustees for the sale of the forfeited estates in Ireland, ‘A list of the claims as they were entered with the Trustees, at Chichester-House on College Green, Dublin on or before the tenth of August 1700,’ J. Ray, Dublin, 1701, p. 293. Entry no. 2530.

[xxxiv] Agnew, Rev. David, C.A., Protestant Exiles from France in the reign of Louis XIV, private circulation, pp. 362-3; Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2.

[xxxv] N.L.I., Dublin, D. 7409. Articles of agreement between Frederick Trench of Garbally, Co. Galway, W. Trench of Redcastle, Queen’s County and their sister Lucy, March 1715.

[xxxvi] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2.

[xxxvii] P.K. Egan, The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, p. 133.

[xxxviii] Sir B. Burke, A genealogical and heraldic history of the Landed Gentry of Ireland (rev. by A.C. Fox-Davies), London, 1912, p. 700; Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 150-2; Cooke-Trench, T.R.F., A Memoir of the Trench Family, privately printed, 1897, p.34; Le Poer Trench, R., 2nd Earl of Clancarty, Memoir of the Le Poer Trench Family, Dublin, privately printed, 1874, p. 7.

[xxxix] Sir B. Burke, A genealogical and heraldic history of the Landed Gentry of Ireland (rev. by A.C. Fox-Davies), London, 1912, p. 700.

[xl] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2.

[xli] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2.

[xlii] P.K. Egan, The Parish of Ballinasloe, its history from the earliest times to the present century, Clonmore & Reynolds, Dublin, 1960, pp. 133-4.

[xliii] Foster, J., The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of the British Empire for 1822, with the Orders of Knighthood, Westminster, Nicholas and Sons, Chapman and Hall, 1882, pp. 35-7, 150-2; Debrett, J., Debrett’s Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 2, (17th edition), London, G. Woodfall, 1828, pp. 726-8.

[xliv] The origin of Ballinasloe October Fair, J.R.S.A.I., Fifth Series, Vol. 3, no. 1, 1893, pp. 88-9.

[xlv] The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Difussion of Useful Knowledge, Vol. III, London, Charles Knight, 1835, pp. 331-2.